It was a year that started and ended with totally out-of-season weather, and included just about every extreme in between, from hot to cold, wet to dry, and frozen to fire.

Ultimately, 2022 was the product of both persistent climate patterns and trends that have become familiar in recent years, along with the return of several weather features we hadn’t seen in a while.

This post wraps up the past year in North Carolina’s weather and climate in a summary of our recent year-in-review webinar. The recording is available on our YouTube channel.

An Overview of 2022

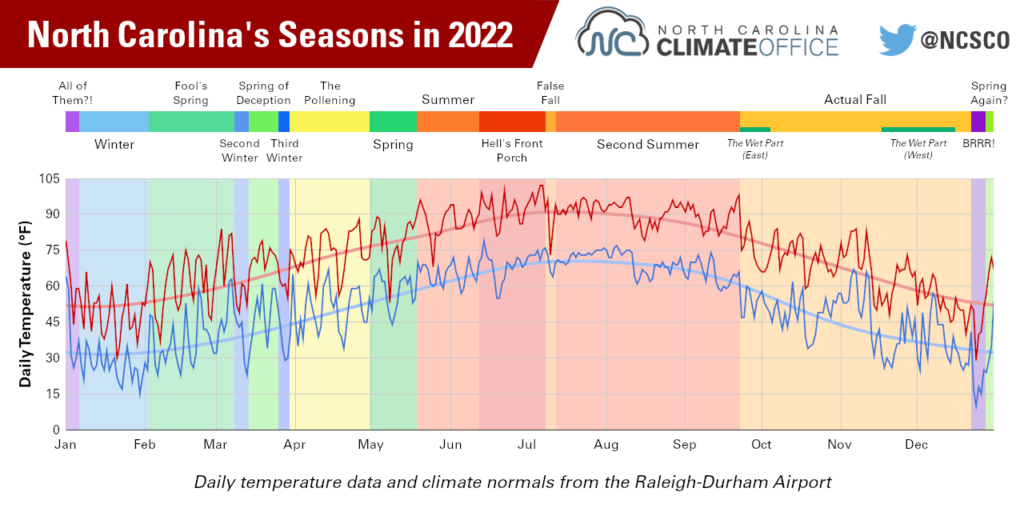

The last calendar year in North Carolina finished with a statewide average temperature of 60.0°F, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), which ranks as our 17th-warmest year on record dating back to 1895.

Several sites had one of their top-ten warmest years on record, including Raleigh (3rd-warmest), Wilmington (tied for the 5th-warmest), Lumberton (tied for the 7th-warmest), and Hatteras (tied for the 10th-warmest). In Raleigh, the 81 days with temperatures at or above 90°F was the 4th-most of any year.

The warmth started early last year, with New Year’s Day high temperatures climbing into the upper 70s. Two days later, a strong cold front sent temperatures crashing down to winter-like levels.

At the end of the year, an Arctic air blast dropped temperatures into the single digits and even negatives on Christmas Eve. Less than a week after that wintry chill, we were back to spring-like weather, ending the year the same way it started.

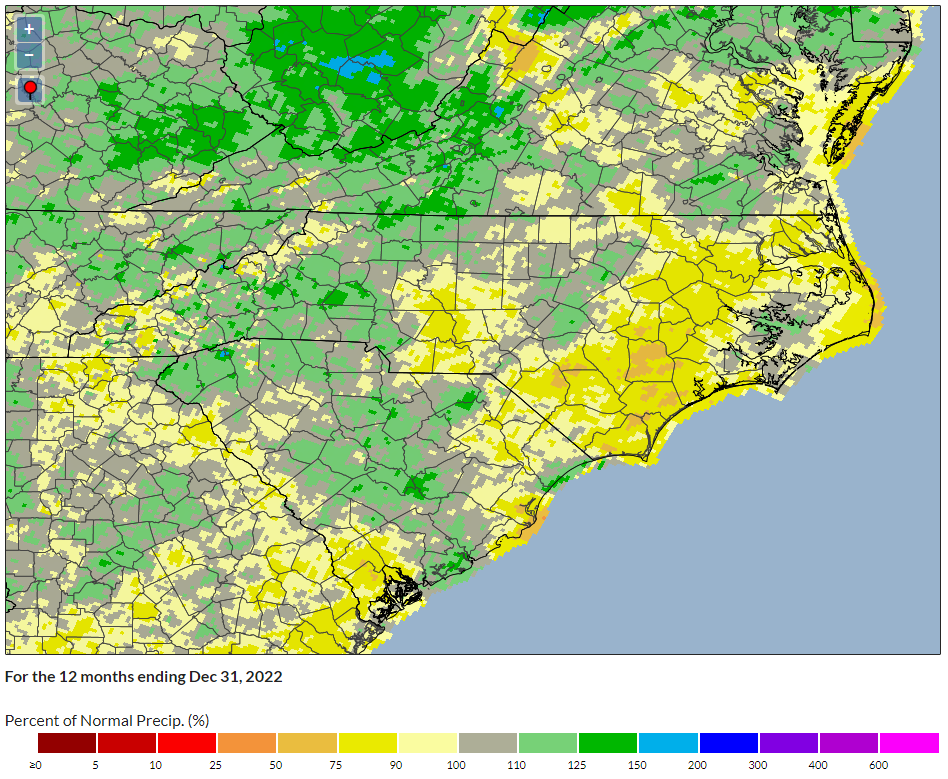

Our precipitation also had plenty of backs and forths throughout the year, but overall, 2022 was slightly drier than normal. NCEI reports a statewide average precipitation of 46.39 inches, or 4.38 inches less than the 30-year average. That made it our 38th-driest year on record in the past 128 years, and the driest since 2012.

Precipitation varied substantially across the state. Areas in the north and west were slightly wetter than normal, including the Triad. Greensboro had its 32nd-wettest year on record and was 3.8 inches above normal.

The wettest spot was Highlands in southern Macon County, with 106.32 inches total. That was its 6th-wettest year on record since 1893 and the 17th time – including each of the past five years – it has eclipsed the 100-inch threshold.

Eastern North Carolina was considerably drier, including Tarboro, which recorded only 33.24 inches – more than 14 inches below normal – and its 7th-driest year on record. Wilmington had just 41.34 inches and was 18.8 inches below normal in its 27th-driest year on record.

A Seasonal Summary

The year began with our dose of winter, neatly packed into the month of January. Four storms in four weeks brought wintry precipitation across the state, including more than a foot of snow in the Mountains during a mid-month storm.

February featured warmer weather that continued through the spring. By mid-May, our high temperatures had already climbed into the 90s, and that was a sign of things to come as the heat cranked up during June, July, and August.

A warm start to September ended with a timely temperature drop on the first day of astronomical fall, and seasonable weather continued through October. November warmed up once more, while December’s warm beginning and end were balanced by our Christmas cooldown.

All four seasons last year finished with statewide average temperatures at or above the 1990 to 2020 average – the fourth time that has happened since 2016. Each season was also drier than normal, which was the first such occurrence since the drought-plagued 2007.

| Season | Temperature Ranking (Departure from 1991-2020 Avg.) | Precipitation Ranking (Departure from 1991-2020 Avg.) |

|---|---|---|

| Winter (DJF) | 10th warmest (+2.4°F) | 45th driest (-1.07 in.) |

| Spring (MAM) | 12th warmest (+1.8°F) | 62nd driest (-0.34 in.) |

| Summer (JJA) | 12th warmest (+0.7°F) | 35th driest (-1.70 in.) |

| Fall (SON) | 46th warmest (±0.0°F) | 61st driest (-2.02 in.) |

Drought was also present in North Carolina for most of 2022, but at nowhere near the extreme levels as 15 years ago. That’s largely because last year’s dryness was subtle but stubborn, easing and fading, and even skipping around the state from east to west and back again.

That was particularly apparent in the fall. Cool, dry weather in the Mountains initially made for ideal leaf colors in October, but eventually degraded into Severe Drought (D2). Meanwhile, eastern North Carolina was soaked by the remnants of Hurricane Ian in late September to tamp down emerging drought there.

That pattern flip-flopped by mid-November. Beginning with the remnants of Hurricane Nicole, the Mountains entered a wetter pattern while the coast missed out on that rain and slipped back into Moderate Drought (D1), which remains in place as we begin 2023.

A viral social media meme claims that North Carolina actually has 12 seasons, and those match up surprisingly well with our weather in 2022. From the March cool snaps surrounding the “Spring of Deception” to “The Pollening” in April to our heat-busting “False Fall” on July 10, it was indeed a year with those temperamental North Carolina temperatures that can feel like all four seasons in one day.

Sectoral Impacts

The agriculture industry, which accounts for 17.5% of jobs in North Carolina and an economic impact of more than $90 billion, enjoyed a generally productive year in 2022. Crops such as cotton, soybeans, and sweet potatoes – for which North Carolina is the leading producer nationally – were all in good condition and ahead of their usual progress targets last summer and fall.

However, the ongoing droughts did take a toll on some crops, particularly corn. The dry June – coinciding with the key development phase of silks, which pollinate the corn and kick-start kernel formation – diminished some corn quality for the rest of the season, while eastern corn was affected by the warm, dry September weather later in the growing season.

Drought also made it an active year for wildfires. Preliminary statistics from NC Forest Service note 6,358 wildfires on state and private lands, which was the most since 2007, and a total of 25,668 acres burned, which was the most since 2016.

While most of last year’s fires were small, there were a few larger ones as well, including the Juniper Road Two fire, which burned more than 1,200 acres on Holly Shelter Game Land in August.

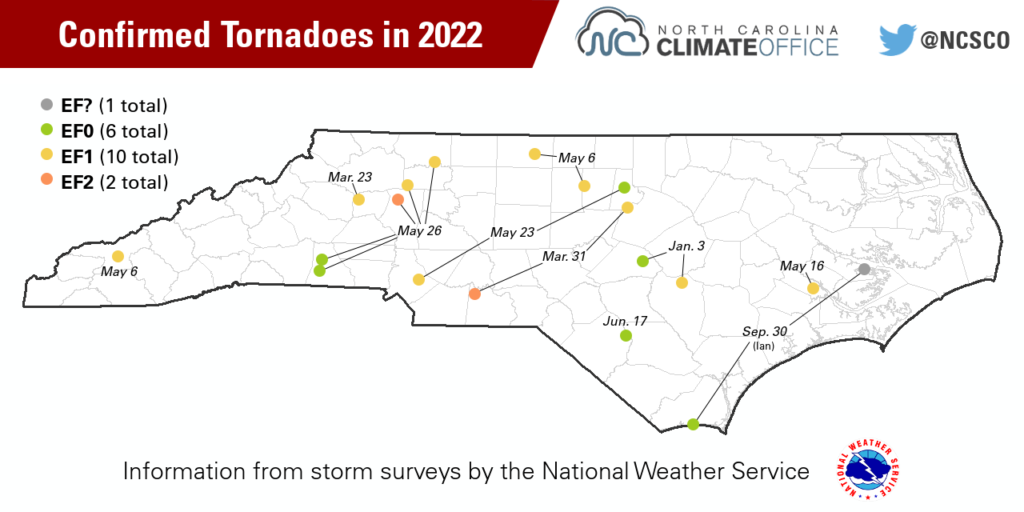

Severe weather started early in the year, with two confirmed tornadoes on January 3, but there were also some quiet stretches. No tornadoes occurred in April – the climatologically most common time of year for them – and after a pair of tornadoes during Hurricane Ian on September 30, there were none in the final three months of the year.

In total, we had 19 confirmed tornadoes in North Carolina in 2022, which matched our 2021 activity but was down from the 30-year average of 31 per year.

The tropics sent three systems our way last year, but with some long gaps in between them as well. After the short-lived Colin slid up the Carolina coast in early July, there were no named storms in the Atlantic for almost two months.

The activity picked up in September, and the remnants of Ian reached us at the end of the month, bringing gusty winds and heavy rain across the eastern part of the state. Ian’s wind-driven storm surge pushed the Cape Fear River in Wilmington to its fifth-highest crest on record, and the storm caused more than 360,000 power outages across the state.

In November, the season’s final named storm, Nicole, moved inland after its Florida landfall and brought heavy rain to the western half of North Carolina. Some localized flooding was observed in the Mountains, but Nicole’s rain was more beneficial than harmful for our drought-affected western region.

Familiar Feelings

Returning to our theme for the past year, it included some recurring patterns and trends with our climate.

While all four seasons were drier than normal overall, there were some quick changes from wet to dry throughout the year, similar to what we noted about 2021. After a dry June, July brought heavier rains that eventually – and briefly – wiped away drought across the state. The fall tropical systems were also preceded by or followed by lengthy dry stretches that helped drought develop.

Last fall, drought emerged at almost the exact same time as in October 2021, and it was again most prevalent across the Coastal Plain as we headed into this winter – the third La Niña event in a row in another familiar-feeling aspect of last year’s weather.

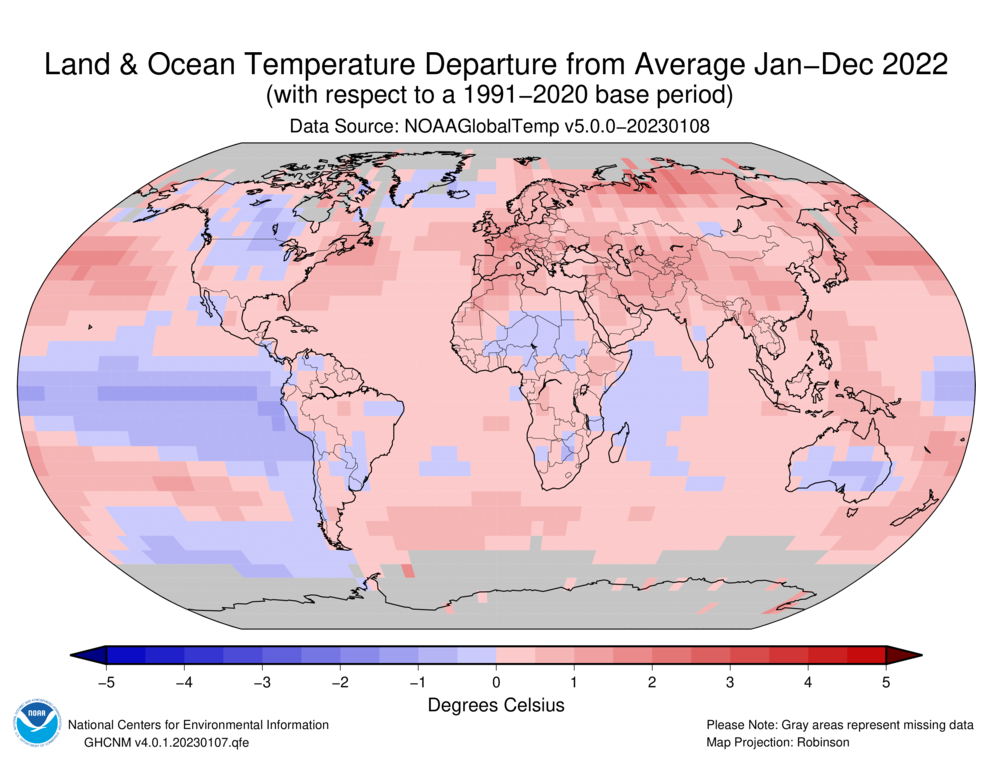

Perhaps most notably, the steady warmth all year long left 2022 among our state’s top 20 warmest years on record. That’s a ranking we’ve become accustomed to, as each of the past eight years, and 12 out of the past 17, have been warmer than the 1991 to 2020 average.

It’s not just North Carolina, of course. Nationally, it ranked as the 18th-warmest year since 1895 according to NCEI. Globally, the average temperature in 2022 was 1.6˚F above the 20th century average and the 6th-warmest year since records began in 1880, according to NOAA. The world’s top ten warmest years have all occurred since 2010.

Last year’s high ranking occurred even despite the ongoing La Niña, which tends to cool global temperatures. However, the heat-trapping impacts of atmospheric greenhouse gases outweighed the normal cooling effects of a La Niña.

The globe experienced its share of climate impacts last year, including record-breaking heat in the US and Europe and catastrophic flooding in Pakistan. Across the country, there were 18 billion-dollar weather and climate disasters in 2022, including hurricanes Ian and Nicole.

Returning Weather Features

Along with those recurring patterns in North Carolina, the past year also had some what’s-old-is-new-again twists.

January’s multiple snow events helped end some long-running “snow droughts,” as more than an inch of snow fell in parts of the Sandhills for the first time in more than four years.

Following two straight years with mild ends to spring, the heat cranked up early in 2022, with the first 90-degree day on May 19 occurring near the typical timing for many Piedmont and coastal locations.

On the other end of summer, we avoided the heat overstaying its welcome and instead saw a timely arrival of fall-like weather, including our coolest October statewide since 1992.

Finally, our persistent dry pattern – driven in part by La Niña – made it the second consecutive drier-than-normal year. Those back-to-back dry years ended a wet stretch in our recent climate, including our wettest and 2nd-wettest years on record in 2018 and 2020, respectively.

While 2022 did not challenge for any such outright extreme rankings, we’ll likely remember it for its weather variety, including both tropical storms and stretches of sunny, dry weather within the same fall season; its overall warmth, especially through summer, with cooler January and Christmas conditions notwithstanding; and the persistent dry pattern that made drought a mainstay – but fortunately, never an exceptional impact – throughout the year.