Our scattered showers were exactly that last month, while our temperatures turned up during two stretches of extreme heat. Both have caused expanding dryness and drought across North Carolina.

Dry Weather Dominates

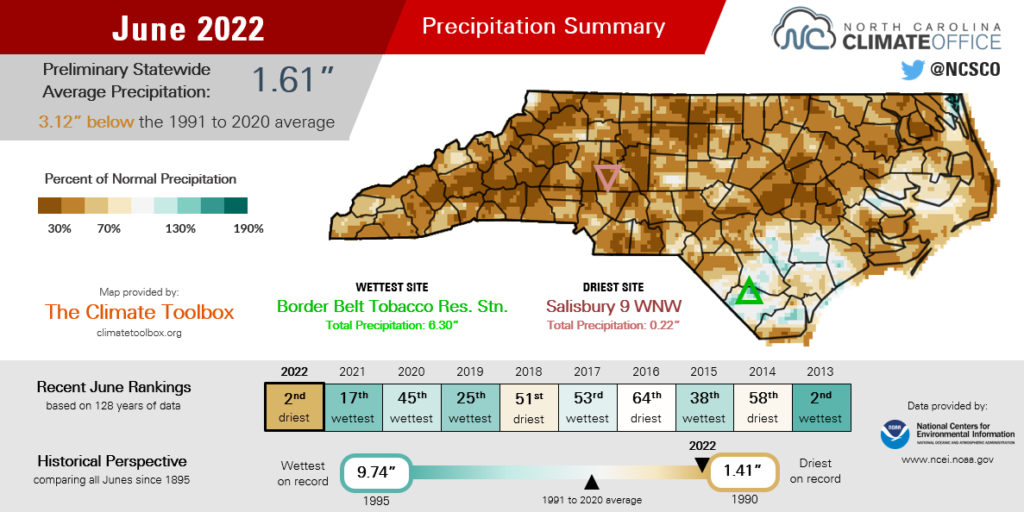

Rain was tough to come by last month, and as a result, we had our driest June in more than three decades. The National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) reports a preliminary statewide average precipitation of 1.61 inches and our 2nd-driest June since 1895.

The month started with encouraging signs, especially at the drought-affected southern Coastal Plain. On June 2 and 3, a cold front brought more than 2 inches of rain in some areas, including 3.48 inches in Wilmington.

After that, the moisture was mostly missing, even during otherwise intense thunderstorm events. A line of fast-moving storms on Friday, June 17 brought wind gusts exceeding 40 mph across the Piedmont and Sandhills, and it caused more than 240,000 power outages across the state. However, even the hardest-hit areas picked up less than half an inch of rain as those storms raced through.

For the final two weeks of the month, high pressure in place over the Southeast largely blocked any frontal systems and suppressed pop-up afternoon shower activity, which left us in an extended streak of very dry weather. From June 17 to 30, Wilmington measured just 0.16 inches of rain and New Bern had only 0.26 inches.

The month overall was also an historically dry one for many areas, especially across the western Piedmont. Salisbury recorded 0.22 inches of rain all month, which was the driest June there since 1954. Hickory’s total rainfall of 1.22 inches ranked as the 5th-driest June since 1959, while Lincolnton had 1.51 inches and its 6th-driest June on record.

At the coast, Tarboro received only 0.86 inches of rain for its 3rd-driest June in 130 years. Kinston had 1.55 inches and its 5th-driest June in the past 50 years, while Newport recorded 1.67 inches all month for its 2nd-driest June since 1996.

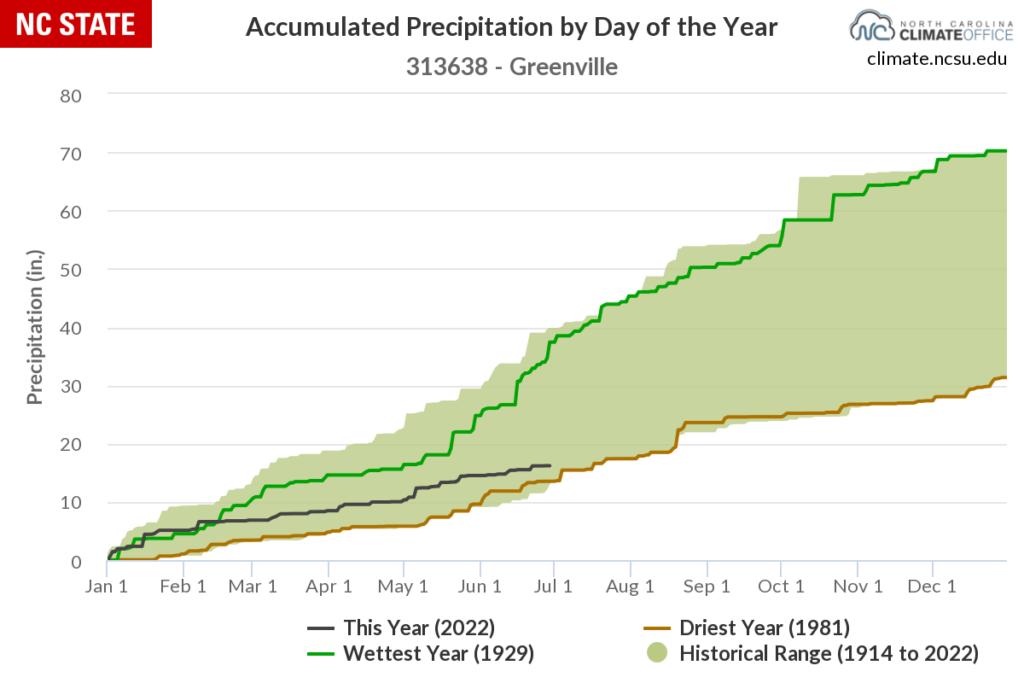

For some eastern areas, June continued a dry stretch that began during the spring, or even earlier. Lumberton is now 4.5 inches below normal over the past three months, which is its 5th-driest April-through-June stretch in the past century. Since January 1, Greenville has had only about two-thirds of its normal rainfall, ranking as its 3rd-driest start to a year out of 86 years with observations.

The Heat Hits Hard

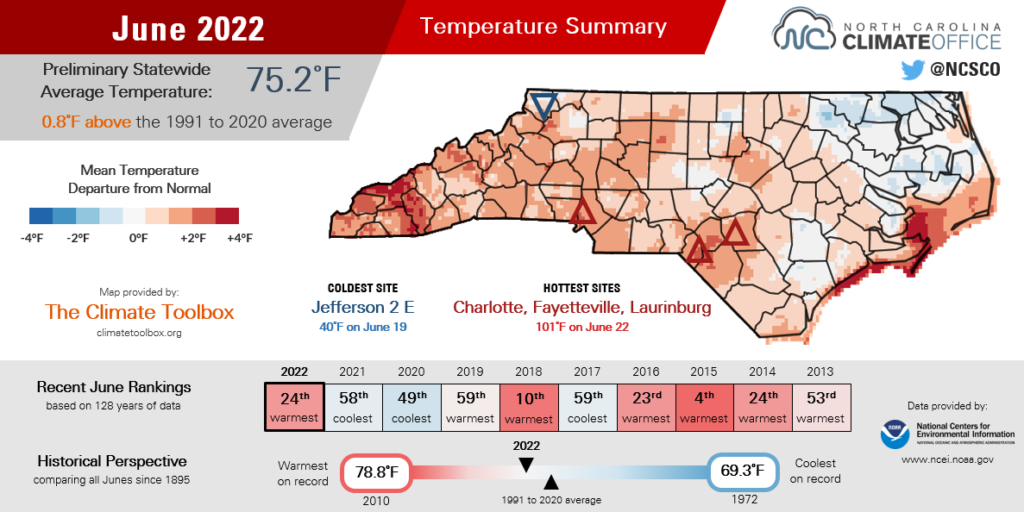

A mid-month run of scorching heat elevated our overall mean temperatures as well. NCEI notes a preliminary statewide average temperature of 75.2°F, which ranks as our 24th-warmest June in the past 128 years.

Locally, it was tied for the 5th-warmest June in Lumberton with an average temperature of 80.1°F, and tied for the 12th-warmest in Raleigh dating back to 1887.

Our temperatures were tempered by a few cooler and less humid days and nights, including on June 19, when lows dipped into the 40s in the Mountains and the 50s elsewhere. But that cool night came after a week of extreme heat, and was only a brief interlude before the mercury rose once again.

Between June 13 and 18, high temperatures reached the upper 90s across parts of the state each day. During that stretch, Charlotte reached 98 degrees three times in five days. That was the warmest June weather there since 2015. Farther west, Marion had a high of 96 degrees on June 16, which was its warmest June temperature since 2011.

The mercury climbed even higher on June 22. Parts of the southern Piedmont hit the century mark, including readings of 101°F in Charlotte, Fayetteville, and Laurinburg. It was the first hundred-degree heat in the Queen City in any month since July 2012. In Raleigh, which hit 100°F on June 22, this was the second summer in a row with temperatures that high following a 100-degree high on August 13, 2021.

Unfortunately, history suggests that when the heat ramps up in June, it tends to stick around for the rest of the summer. In 2018, which included our 10th-warmest June on record, we saw 90-degree temperatures through mid-September. And 2011 and 2015, which both had hot Junes, finished with our 2nd-warmest and 8th-warmest summers on record, respectively.

In other words, in North Carolina, there’s no such thing as getting the heat out of the way early in the season. As we enter our climatological warmest month in July, expect more of the same hot weather to continue.

Drought Lingers and Expands

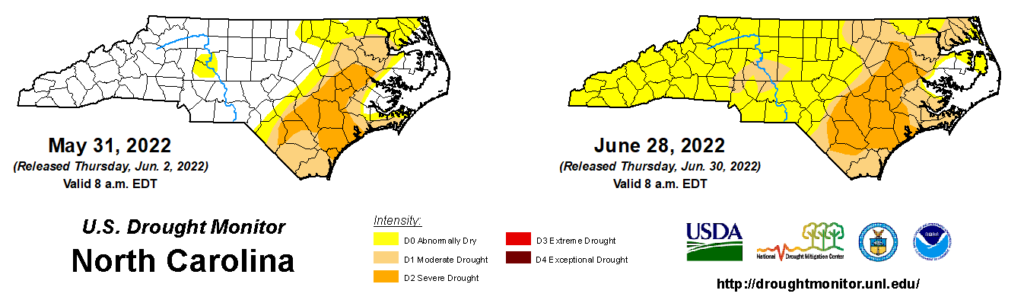

Our hot days and limited rainfall have most of the state feeling the stress of dry weather and drought. During June, Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions spread across the western part of the state, while drought expanded in the Coastal Plain and a pocket of Moderate Drought (D1) emerged in the western Piedmont.

Some of the main signs you’ve probably noticed are your grass or garden growing slowly or not at all, and perhaps leaves or lawns turning yellow or brown. While it’s not uncommon to see that during our hottest summer days, the duration of those impacts and the recent lack of rainfall has become notable, hence the Abnormally Dry designation.

It’s affecting farmers as well, particularly with the corn crop entering its critical silking period. As the silks, or thread-like strands extending from an ear of corn, are pollinated, kernels eventually form. But because of their high water content, silks are very sensitive to a lack of moisture, and in times of severe drought, the silks may not emerge at all, leading to incomplete kernel development.

As of June 26, USDA/NASS reports that only 39% of corn has reached the silking phase, compared to the five-year average of 50%. And some farmers have noted that corn leaves are rolling up or turning brown – also signs of moisture stress. Crop losses are a typical impact in Severe Drought (D2), and a reduced yield now appears likely for some crops in eastern North Carolina.

Surface water sources are also feeling the effects of a hot, dry June. Recent streamflows are mostly below normal across the eastern two-thirds of the state, and many across the Coastal Plain are below their historical 10th percentile for this time of year.

Most major reservoirs in the Piedmont have dipped about a foot below their seasonal target levels, and operators such as the US Army Corps of Engineers and Duke Energy have reduced downstream water releases to hold onto as much storage as possible.

While the supplies from these reservoirs are currently sufficient to meet demands, some coastal water systems without such significant storage have begun to implement water restrictions. On June 16, Brunswick County recommended voluntary water conservation, including a suggested reduction of daytime outdoor use, and irrigation on alternating days.

Widespread water restrictions have historically been confined mostly to our longest-lived, multi-year drought events. Our current drought – which first took root in the fall before abating but not totally disappearing over the winter – has now persisted across parts of the state for 36 weeks and ranks as our state’s fifth-longest drought since the US Drought Monitor began officially tracking conditions in January 2000.

| Consecutive Weeks with Drought in NC | Drought Started | Drought Ended |

|---|---|---|

| 155† | Jan. 4, 2000 | Dec. 17, 2002 |

| 117 | Feb. 13, 2007 | May 5, 2009 |

| 100 | Jul. 6, 2010 | May 29, 2012 |

| 53 | May 3, 2016 | May 2, 2017 |

| 36 | Oct. 26, 2021 | in progress |

So how long will it last? It’s impossible to say for sure, but past years with drought in place exiting June offer some clues about how this drought may evolve and, eventually, end.

Sometimes, we only need to wait for the tropics to send a storm our way later in the summer. In 2011, the Extreme Drought (D3) at the coast significantly improved after Hurricane Irene in late August, and the 2019 coastal drought was done in by Dorian in September.

In other cases, early-summer drought set the stage for further worsening later in the year. In 2016, Severe Drought first emerged in the Mountains in June, and it eventually degraded into Exceptional Drought (D4) that fall with many large wildfires across the landscape. The historic 2007-09 drought also intensified during the hot summer of 2007 before hitting its peak severity during the dry fall that followed.

With the worst drought conditions remaining at the coast for now, our best bet this year also seems to be a timely tropical storm or two, and that at least seems possible, given the forecast for above-normal activity in the Atlantic.

Of course, if our hot, dry June weather is a sign of things to come for the rest of the summer, then we could have a more widespread drought in place and need even more rainfall across a wider area to fully recover.

In any case, history tells us the heat is probably here to stay this summer and pop-up showers alone don’t cut it for replenishing our lakes, streams, and soils. So whether it’s by irrigating in the mornings or evenings, using rain barrels, or living with an ugly brown lawn for a while, it’s not a bad idea to save the moisture we’ve got until the skies open up again.