Moderate Drought conditions emerged in southeastern North Carolina last week, which was a rude reminder that it’s been a while since we’ve dealt with drought. A wet 2020 that carried over into a surprisingly wet winter this year meant flooding and saturated soils have been the bigger problems over the past 18 months.

Among the North Carolina Drought Management Advisory Council — the group in charge of monitoring drought in the state, issuing drought advisories, and making recommendations to the US Drought Monitor — a common refrain earlier this year was that “it’s been so wet for so long, we’ve forgotten what dryness looks like.”

Indeed, amid these hydrologic heydays — we previously hadn’t been in drought since November 19, 2019 — it has been easy to forget exactly how drought events can take shape and what impacts they can have, especially during the spring and summer months.

We hope this post isn’t a preview of how bad things will get this year, but more of a primer for what past droughts at this time of year have meant for North Carolina.

Read through this full FAQ, or skip ahead to see where drought has already emerged, what impacts we expect soon, how you can prepare, and how bad historical spring and summer droughts have gotten — and how they’ve ended.

When and where did the recent dryness emerge?

Early March saw the timely arrival of spring-like weather following a cool, wet February. Unlike in the winter, our cold frontal passages this spring have brought limited moisture east of the Appalachians, so rainfall has become infrequent, especially in southeastern North Carolina.

Through mid-April, few people could complain about the pattern change. For farmers, their fields were workable for the first time since last fall, and reservoirs such as Fontana Lake in western North Carolina finally moved into the normal operating range after spending much of the winter above the seasonal flood guide.

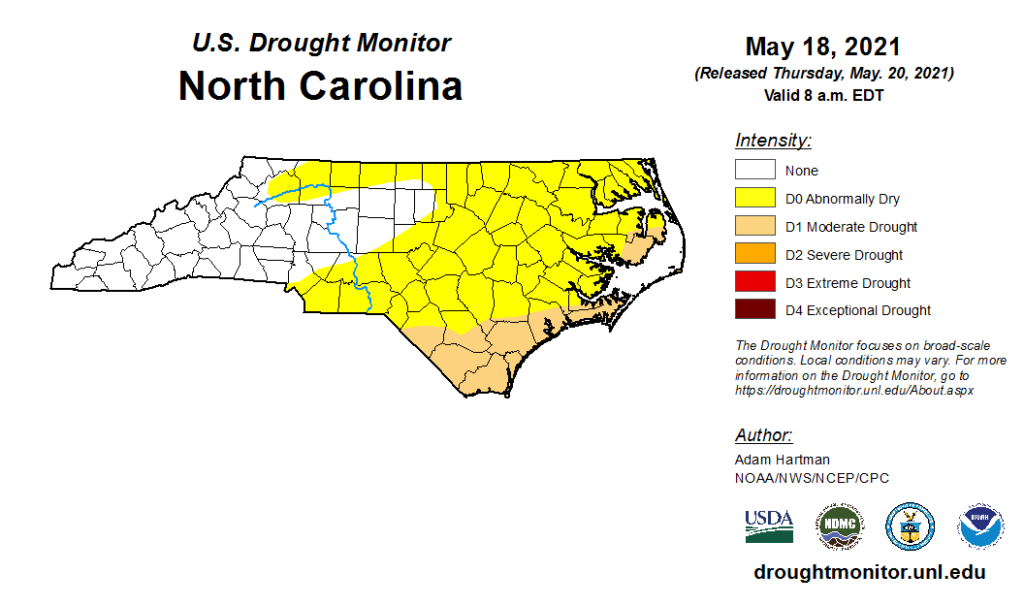

Over the past month, we’ve edged beyond typical springtime dry weather. Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions first emerged across the southern Piedmont and Sandhills during the week of April 20, and expanded to cover half of the state the following week.

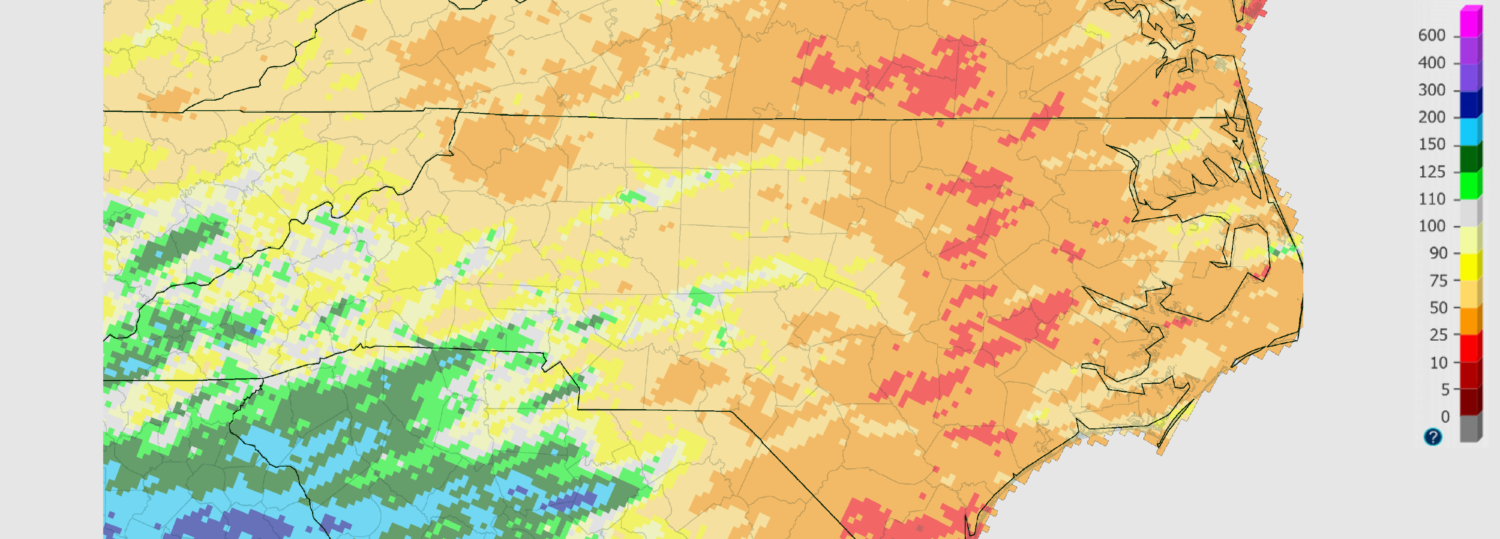

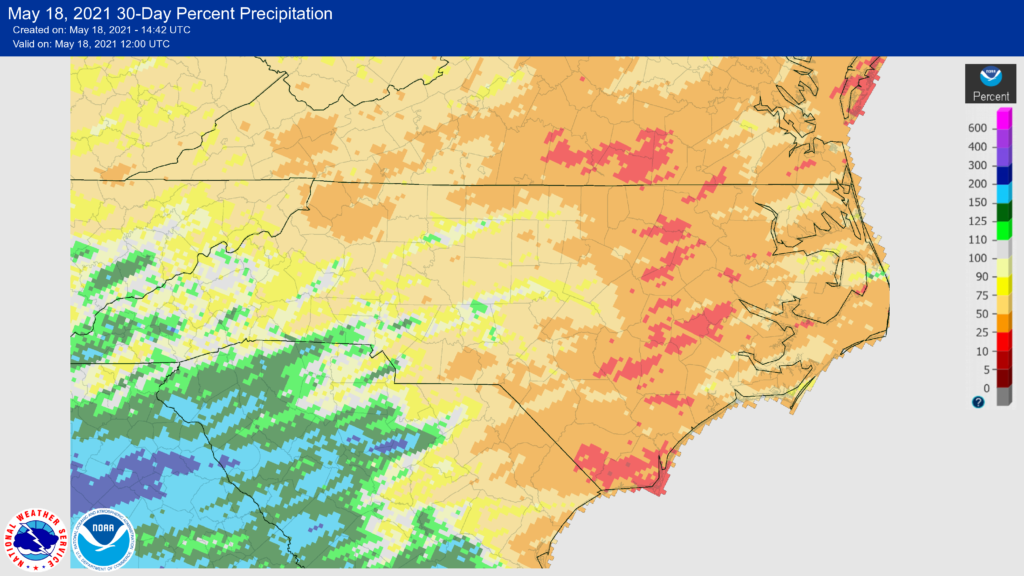

Last week, Moderate Drought (D1) was introduced across the southern Coastal Plain and Outer Banks, covering 12% of the state overall. These areas have seen the driest weather recently, including the 2nd-driest spring-to-date on record at Ocracoke, where they’re 6.6 inches below normal since March 1, and the 6th-driest spring in Wilmington, which is 5.4 inches below normal so far this season.

Cooler temperatures and spotty showers at the coast prevented any additional drought expansion this week, but parts of the northern Coastal Plain, northern Piedmont, and northern Foothills are now classified as Abnormally Dry on the current map.

Is there any cause for concern at the moment?

One bit of good news is that our excess moisture from the winter continues to shield us from a quicker or more widespread drought emergence this spring. In fact, much of the state is still above its normal precipitation over the past six months.

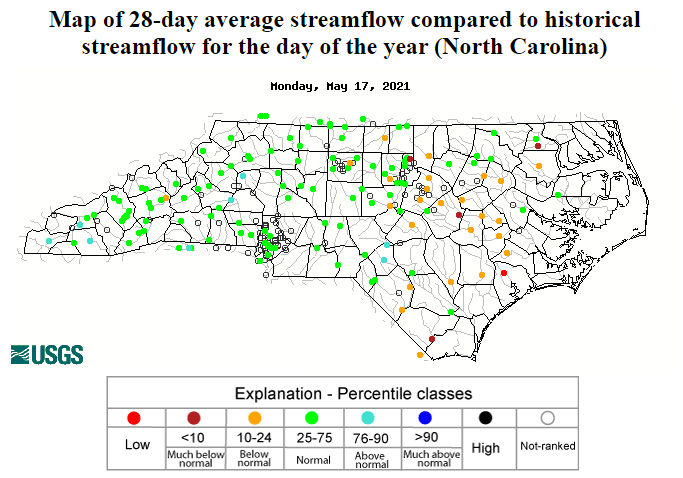

Groundwater and streamflow levels were near record highs coming out of the winter, and even with their recent declines, we have fewer concerns about water supply at the moment. Nevertheless, if conditions remain dry, increased evaporation and greater water demand over the summer could prevent reservoirs from maintaining their target levels.

While our short-term precipitation deficits are growing, they’re not unmanageable just yet. Wilmington is 2.7 inches below normal for the past 30 days, but that could be overcome with one wet month. For instance, last June was 5.9 inches above normal there!

How does this compare to other spring drought events?

While we’ve been drought-free for a while, we only need to go back two years to find drought conditions that emerged in the same part of the state at the same time of year. By late May in 2019, the southern coastline was classified in Moderate Drought, with Abnormally Dry conditions covering eastern North Carolina and the far northern Piedmont.

That drought developed after a particularly dry May — the 3rd-driest for Wilmington dating back 147 years, with only 0.63 inches of rain all month, including a stretch of 18 consecutive days without measurable precipitation. (For reference, Wilmington has received 0.75 inches so far this May.)

The eastern half of the state also experienced drought throughout the spring and summer of 2011, but it first emerged earlier in the year during a very dry winter. By the end of May in 2011, Severe Drought (D2) was already in place along the coast.

The western part of the state hasn’t seen the widespread emergence of springtime drought conditions since 2007, but areas just west of Charlotte and the Triad did experience a fast-emerging drought in June 2015 during the hot, dry start to summer there.

What impacts might we see in the next few weeks?

As we enter the summer season, our temperatures will continue getting warmer and our precipitation more localized as it will increasingly come from pop-up showers and storms. Even if you’re not in an area currently classified as Abnormally Dry or in drought, you may start to notice some signs of dryness if several hot, rain-free days stack up together.

For example, lawns may turn yellow or brown, and newly planted seedlings and gardens may need to be watered more frequently. Wildlife get thirsty too, so consider keeping a bird bath or shallow bowl — with some rocks for birds and insects to perch on — filled with water in case their normal sources such as small creeks run dry. Just be sure to empty and refill it regularly to avoid mosquito larvae.

The spring fire season is currently winding down as vegetation is almost fully greened up, which makes it less flammable and better able to retain moisture. However, that doesn’t mean fire danger is non-existent, especially if conditions continue to dry out.

Trees may drop their oldest leaves to conserve water, and you’ll still want to use caution with any burns since fires could spread quickly across a dry landscape. Whether you’re burning backyard debris or lighting campfires and barbecues this summer as restrictions on gatherings are lifted, make sure to stay informed about local fire danger and any burn bans in effect.

Will the drought affect my food supply?

Locally grown crops may be less productive due to the drought, but that depends on the time of year as well. Corn is heavily dependent on rain during the critical silking period, which typically occurs in June. If we don’t see suitable conditions during this window, corn yields could be negatively impacted for the whole season, even if normal conditions return later in the summer.

In 2019, the drought peaked at harvest time in September and October, so many crops were salvageable if slightly underdeveloped, while others like soybeans suffered since they needed a few extra weeks to finish maturing. At this point, it’s too early to tell exactly how the rest of the growing season might look this year.

If you prefer to pick from your garden, then this dry air looms over your heirlooms. During a drought, some plants may not be as productive or might require more watering. Temperatures are a factor, too. If it’s also very warm, especially at night, plants like tomatoes may grow more slowly.

Will water restrictions be implemented?

In some areas, the answer is almost certainly yes, but it depends on how the drought progresses.

For comparison, during the coastal drought in 2019, parts of Pender County limited “all non-essential uses of drinking water”, including a ban on irrigating grass lawns, by late June. In July 2015, many municipalities within the Catawba River basin requested voluntary water conservation.

In our more severe droughts, some state-level guidance may be issued. During the 2007 drought, which first emerged in March, the governor requested voluntary conservation measures in the drought-affected Mountain counties at the end of May, expanded that request across all 100 counties in late June, and in August advised a 20% reduction in water consumption as more than half of the state was also under restrictions from their local water systems.

In short, your area could see either voluntary or mandatory restrictions introduced next week, next month, or not at all, depending on how severe and long-lived the drought is, plus characteristics like where your water supply comes from, how many customers pull from that source, and how upstream rainfall (or the lack thereof) keeps rivers and reservoirs recharged (or depleted) this summer.

What can I do now to prepare?

It’s never too early to establish some good habits, since they can help save money along with saving water. For example, installing low-flow or efficient fixtures such as shower heads, faucets, and toilets can make it easier for your household to absorb water use cutbacks, if they are implemented.

In your lawn and garden, adding a rain barrel can help capture water to use for irrigation. Plant native and drought-tolerant species when possible, and be conscious of where you plant them, since it can keep them healthier and help them withstand environmental stress. In southeastern North Carolina, some plants are already showing signs of stress.

“I have noticed large, mature trees starting to wilt, which was what really caught my attention,” said Emilee Morrison with the Onslow County Center for NC Cooperative Extension.

“I can also say that one really learns which plants are most important to them during times of drought since watering can take a lot of time and energy. From that perspective, planting things with higher water needs close to a water source can be very helpful when supplemental irrigation is needed.”

Since drought can be associated with increased fire risk, some Master Gardener Volunteer programs in the state are participating in Fire-Resistant Landscape training through UGA. Check with your local Extension agent for more information on fire-resistant landscaping.

More broadly than just water use, be aware of your overall energy use. Hot summer weather means more time using air conditioning, and energy sources may struggle to keep up with that demand, especially if you’re supplied by hydroelectric power, which accounts for about 5% of North Carolina’s total electrical generation.

How bad will it get?

At this point, it’s impossible to say. The 2007, 2015, and 2019 droughts all began in one small region of the state, but each evolved differently in the months that followed.

The 2007 drought eventually encompassed the entire state over more than a year, and it became our worst drought in recent memory. The 2015 drought remained largely confined to the western Piedmont and faded by the fall. And the 2019 drought improved at the coast in the late summer, but shifted westward by October.

If the bulk of the summer is hot and dry, we could see a more rapid expansion and worsening of drought conditions, along with impacts such as significant crop losses and mandatory water restrictions. If more regular rainfall returns to all or part of the state, drought may remain regional or localized, and it may evolve more slowly.

In the short term, we do expect further drying and likely drought expansion. The next seven days are forecasted to be extremely dry with high temperatures reaching into the 90s by early next week.

The latest three-month outlook from the Climate Prediction Center suggests above-normal temperatures are likely for North Carolina this summer, although this is based on the 1981-2010 climate normals. The new 1991-2020 normals show an increase of up to 1 degree in our summer average temperatures, so it’s tough to say whether the current outlook still represents a warmer-than-normal summer.

Their precipitation outlook offers elevated odds of above-normal precipitation, although historically, summertime precipitation forecasts are among the least skillful due to the scattered and localized nature of our warm-season rainfall.

When will the drought end?

We can’t say when, but from past droughts, we have a decent idea of how it might end, and that’s probably with a tropical storm or hurricane.

The coastal drought in 2011 ended with Hurricane Irene in August. Rainfall relief finally arrived in early October 2015 with a week of rain from the tropics. And in 2019, drought-affected coastal areas were soaked by Hurricane Dorian.

As we mentioned in our April climate summary, the initial outlook for this hurricane season calls for above-normal activity in the Atlantic, although that’s no guarantee we’ll have a storm locally. Even last year, only one of the record-setting 30 named storms made landfall in North Carolina. However, Hurricane Isaias in early August did provide timely rain for dry areas in the northern Coastal Plain.

How can I get the latest drought information?

You can view the official statewide drought status and advisories on the North Carolina Drought Management Advisory Council’s website, ncdrought.org. We will also post updates on our Twitter feed, @NCSCO, as the updated drought status is released each Thursday morning.

Your local water utility, municipality, and possibly even the state may issue restrictions as time goes on, so make sure to follow their lead and help us weather this drought together, however bad it gets or how long it lasts.