Chalk it up to atmospheric anomalies or a forecast without foresight. Either way, this winter defied expectations and drenched most of North Carolina for yet another season.

According to the National Centers for Environmental Information, the three-month period from December 2020 through February 2021 ranked as our 13th-wettest winter since 1895 based on the statewide average precipitation of 15.26 inches, or 3.83 inches above normal.

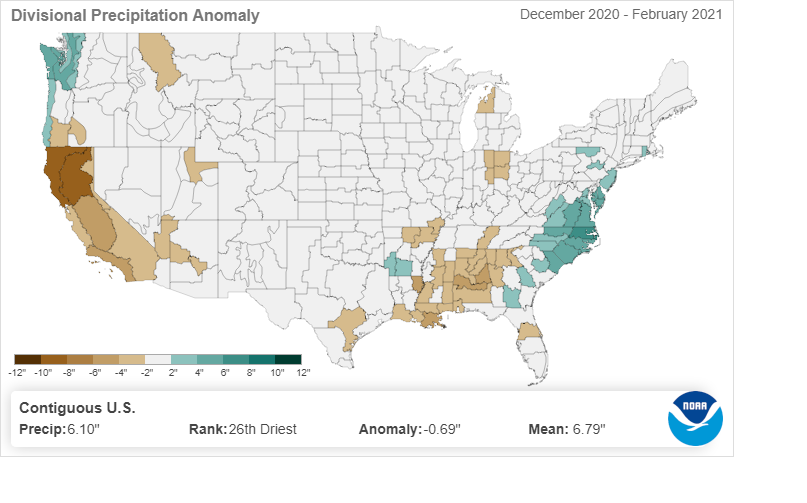

Such wet conditions largely made us the exception on a national level. Most of the country finished the winter with near-normal precipitation. California and parts of the Deep South were a bit drier, while eastern North Carolina through the mid-Atlantic region stands out as wetter.

In fact, among all 344 climate divisions — multi-county regions grouped based on similar geography and climatology — in the continental United States, the northern Coastal Plain of North Carolina was the wettest relative to normal for the winter, at 6.28 inches above normal.

Our temperatures didn’t stand out as much. The statewide average temperature of 41.8°F was just 0.6°F above the 1901-2000 average, and it ranked as our 51st-warmest winter out of the past 127 years, according to NCEI.

Winter average temperatures were cooler than normal in the southern Plains, which had a deep freeze in February, and generally near or above normal elsewhere. The warmth in North Carolina was most notable in our nighttime lows, which ranked as our 37th-warmest in the winter at 1.7°F above normal. This is attributable both to cloudy and more humid nights, along with long-term warming trends associated with climate change.

An Active Atmosphere

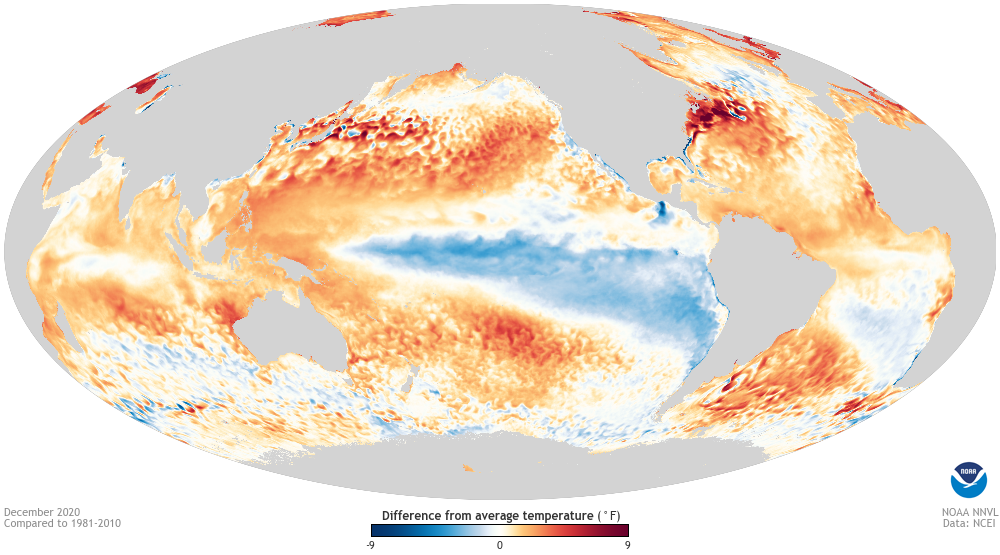

A fairly robust La Niña pattern emerged in the Pacific last fall, and it remains in place now although slightly weaker than it was in November. However, it wasn’t the main driver of our wintertime weather in North Carolina, or even across much of the broader Northern Hemisphere.

One reason could be an unusual aspect of this particular La Niña event. For most of the season, the coolest water in the Pacific was south of the equator, not evenly split on either side of it.

With warmer conditions north of the equator, the subtropical jet stream more closely resembled what we usually see during an El Niño, or ENSO warm-phase event, with moisture-rich storm systems frequently moving in from the Gulf of Mexico.

To that end, NOAA’s ENSO Blog compared the large-scale patterns among 13 strong La Nina events, and 2020-21 was so dissimilar to the rest that they concluded “you can argue that the Northern Hemisphere atmosphere looked a little more like El Niño than La Niña!”

In addition, the polar jet stream, which is the gatekeeper for cold air from the north, was being driven by another phenomenon for part of the winter. In early January, a sudden stratospheric warming event occurred in the upper atmosphere.

These events occur semi-regularly — as NOAA notes, about six times per decade — and can be a shock to the system, reversing the upper-level winds and weakening the polar vortex.

This winter, that resulted in a rush of Arctic air across the central US in February, along with a southward-diving polar jet stream that left North Carolina cool and icy, but mostly just wet.

We’d like to say we could have seen clues for this pattern in our crystal ball last fall. Our winter outlook did at least note similarities with the overall wet conditions leading into the 1995-96 winter, which was largely absent of any drought or dry weather emergence.

And we did mention the chance that “a weakening and southward-diving polar vortex could bring cooler weather”. But as the name “sudden stratospheric warming” implies, those events occur so quickly and with such little warning that pinpointing one and its impacts two months ahead of time would have been impossible.

Wet Weather but Scarce Snowfall

Historically, wet La Niña winters in North Carolina are relatively rare. Since 1950, only six of the 23 La Niña-phase winters (based on the three-month average Oceanic Nino Index) have been wetter than normal statewide. That’s roughly one in four, including 2020-21.

Among those six winters, four had sudden stratospheric warming events, suggesting that even if the cold air isn’t directly invading North Carolina, these events still disrupt the large-scale jet stream patterns enough to affect our winter weather and break La Niña’s usually steady mold.

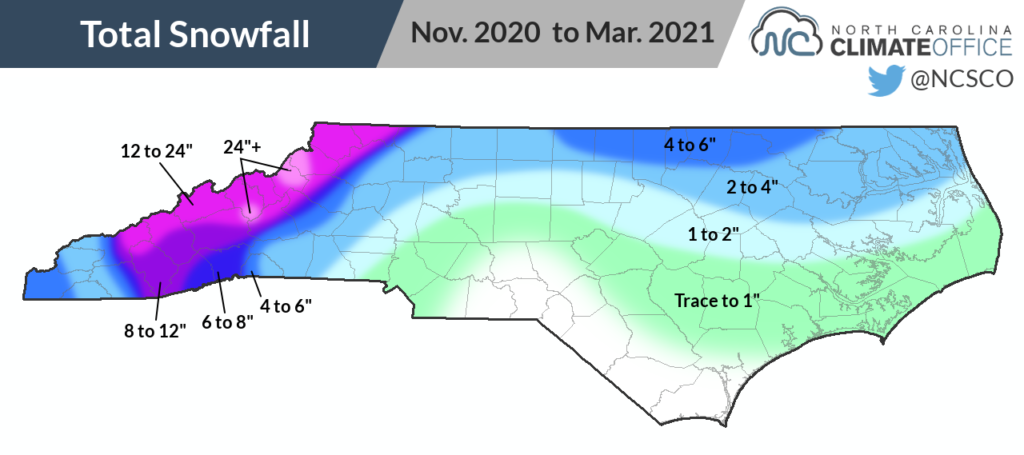

Perhaps the only aspect of this winter that followed the typical La Niña trend was our snowfall — or lack thereof. Outside of the Mountains, the most significant event was on January 28, when up to 5 inches of snow fell along the Virginia border.

Instead of snow, the northern Piedmont had two ice events within a week in February, while the rest of the state had little to no frozen precipitation at all.

This winter’s snowfall map closely resembles the one from last year, so for central, southern, and eastern North Carolina, that meant a second straight winter without much snow.

In Charlotte, it was the second consecutive winter with 0.3 inches of total snowfall. Greensboro had just 1.2 inches — the lowest winter snow total there since 2006-07. And sites such as Fayetteville, Lumberton, and Wilmington had no measurable snow at all for the third winter in a row.

While the Mountains generally saw more snow than last winter, seasonal totals were still below normal. Asheville received 8.0 inches compared to a normal of 9.9 inches, Boone had 21.6 inches versus a normal of 35.3 inches, and Mount Mitchell has a season-to-date total of 59.5 inches, well below the normal of 92.3 inches.

From the Spring, Forward

Just in time for the beginning of climatological spring, the first two weeks of March have brought a decidedly warmer and drier pattern to the Southeast US.

While that’s more in line with La Niña’s typical impacts, it’s hard to credit La Niña since we haven’t seen its telltale bullseye of wet weather over the Great Lakes. Instead, the jet streams are doing their own thing again — in this case, ridging over the eastern US to leave much of the region warm and dry.

Beyond the spring, the ENSO outlook features the typical uncertainty for this time of year. Most forecasts show sea surface temperature anomalies heading back toward neutral territory this summer.

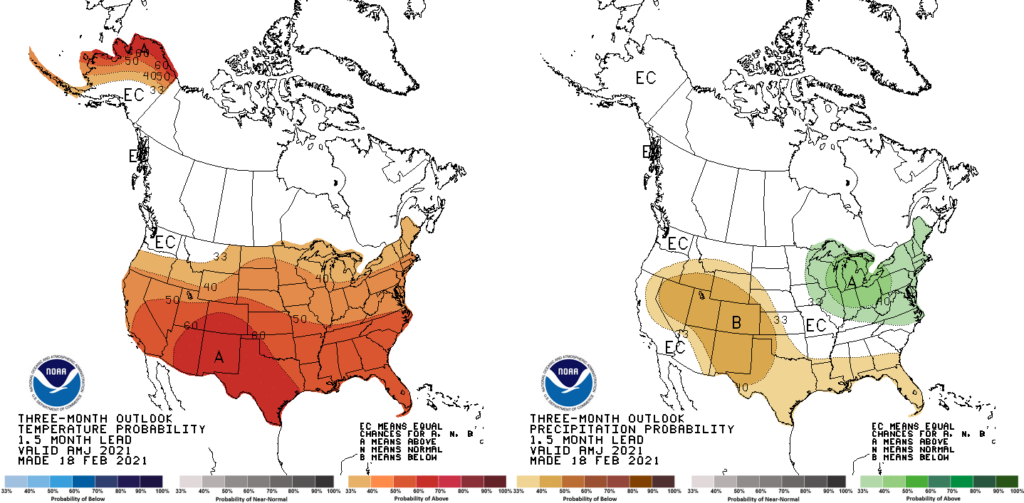

Closer to home, the three-month outlook for April through June shows above-normal temperatures favored across most of the continental US, including North Carolina. That wouldn’t be too surprising since each of our last six springs has been warmer than the long-term average.

The precipitation outlook is less certain, with elevated odds of above-normal rainfall to our north and equal chances of above-, near-, and below-normal rainfall to our south. Statewide, our past six springs have been evenly split between wet and dry, although our wet springs like last year’s — the 5th-wettest on record — have been very wet.

So what will spring bring? If the unpredictable winter is any indication, it could be another season of surprises, left up to atmospheric whims instead of one pattern to rule them all.

As we exit the winter, though, one thing does appear more certain: We may have seen this La Niña’s last impacts on our weather this year, if it ever had any in the first place.