Today we revisit North Carolina’s winter, including a seasonal summary, a review of predictions from folklore and our own winter outlook, and an ENSO update and outlook.

Winter Summary

The meteorological winter — December through February — finished as the 40th-coolest and 33rd-driest winter statewide out of 120 years of record. But the whole winter wasn’t as cool as that figure suggests. We had above-normal temperatures for much of December and near-normal temperatures in January, with little to no measurable snowfall outside of the high elevations in the mountains.

By mid-February, we finally got into a colder pattern, and from Valentine’s Day through the end of the month, it was frigid — highs dropped into the 20s and 30s with lows in the teens or below. We also saw four frozen precipitation events during that two-week period:

- a wintry mix on February 16-17, with light snow accumulations across the northern tier and more than a quarter-inch of ice from the Sandhills across the northern and central Coastal Plain

- a brief round of snow on the 18th, resulting in a dusting across parts of the state

- a light but long-lived snow event on the 24th that brought a rare powdery, dry snow to NC

- another mixed precipitation event on the 25th and 26th brought snow, sleet, freezing rain, and rain; this was the largest snow event of the season for the northern half of the state

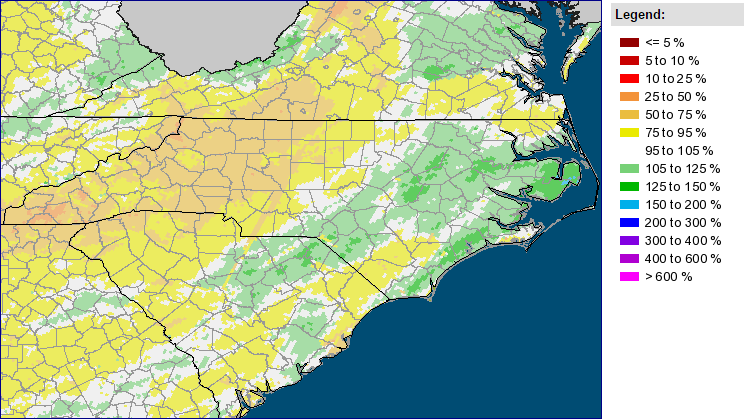

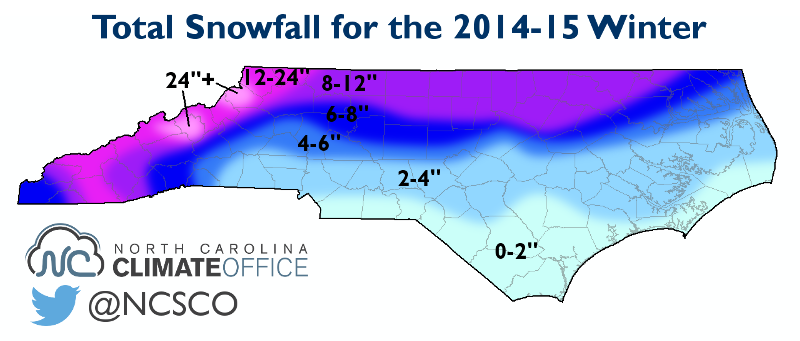

Although our seasonal snowfall was packed into a short period of time, most sites across northern and western North Carolina ended the winter with above-normal snowfall. The Raleigh-Durham Airport (7.9″) and Greensboro Airport (9.6″) both exceeded their normal snowfall by two inches, and Asheville (13.3″) was 3.4″ above normal.

South of there, totals were a bit lower since several precipitation events transitioned from snow to sleet and freezing rain. Charlotte had just 3.1″ for the winter, slightly shy of its 4.3″ normal snowfall. Even across a 25 mile distance in Wake County, there was more than an 8 inch difference in totals, from 3.5″ in Garner to 11.8″ at Falls Lake.

Folklore Review

Back in November, we looked at the forecasts from some popular folklore. Here’s a review of these predictions and how they fared:

- Both farmers’ almanacs agreed on a cold winter with near- or above-normal snowfall. The Old Farmer’s Almanac called for snowy periods in early to mid-January, while the Farmers’ Almanac called for “active wintry weather” in early January and early February.

Verdict: Both forecasts missed the timing — the main cold and wintry period was in mid- to late-February. But they did correctly predict a colder-than-normal winter overall. The Old Farmer’s Almanac also correctly called our drier-than-normal weather.

- Kwazimodo, the winning woolly worm at last year’s Woolly Worm Festival in Banner Elk, predicted cold and snowy weather in December, January, and March, with little snow in February.

Verdict: As we saw, the winter panned out nearly opposite of this prediction, with a warm December and most of our snow concentrated in late February.

- The persimmon seeds collected outside our office suggested a snowy and possibly icy winter.

Verdict: For Raleigh, this interpretation was surprisingly close, as we received a mix of snow, sleet, and freezing rain.

- On February 2nd, Sir Walter Wally, Raleigh’s own groundhog, did not see his shadow and predicted an early spring.

Verdict: Wally probably wanted to climb back in his burrow in the weeks after his prediction, as the worst of winter was yet to come.

Our Forecast Review

In our winter outlook released in November, we called for overall below-normal temperatures, above-normal precipitation, and above-normal amounts and occurrences of snowfall and frozen precipitation.

A few of our predictions panned out. We had two significant winter storms in late February, and we finished the winter with below-normal temperatures, on average. Parts of the state also saw above-normal snowfall, with sleet and ice elsewhere. Also, this year’s total snowfall matched up well with the average snowfall from the five analog winters we looked at, at least for northern and western North Carolina.

However, the expected cooler pattern never materialized in December and January. Also, we were on the dry side overall and didn’t necessarily have an above-normal number of days with frozen precipitation, especially in January.

So why didn’t some of the winter play out as we expected?

First, the El Niño event that seemed inevitable in November was slow to develop, so its impacts on the Southeast US were weak or non-existent. Although there was a persistent ridge over the western US, that was due more to the warm-phase Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) pattern. We didn’t see strong troughing over the east coast until February, and until then, most storms tracked to our north, bringing storm after storm to Boston and other parts of New England.

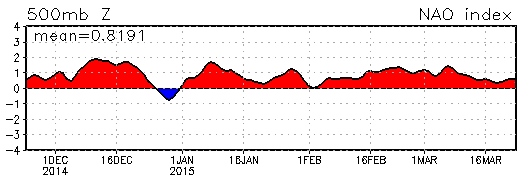

The polar jet stream also didn’t respond as expected to the October buildup of snowfall over Siberia or stratospheric easterlies. For the second straight winter, we saw few negative-phase Arctic Oscillation or North Atlantic Oscillation events, which meant limited opportunities of seeing wintry weather.

It’s tough to explain exactly why the jet stream didn’t behave as anticipated, but one reason is that the easterly winds in the upper atmosphere — indicated by a strongly negative Quasi-Biennial Oscillation phase — never migrated down to the jet stream level. In fact, we saw even stronger stratospheric easterlies in February than we did in November, which tells us that the wind pattern really hasn’t changed.

ENSO Update and Outlook

Although an El Niño event didn’t arrive in time for the winter, a weak one has emerged over the past month or two. In early March, the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) issued an El Niño Advisory, indicating that El Niño conditions are present and expected to remain in the coming months.

If you look at the current Pacific sea surface temperature anomalies (left), you’d be forgiven for asking “What El Niño?!” The current conditions, with the warm anomalies centered in the west-central Pacific, don’t fit the bill of a classic El Niño event. But along with the warming water in recent months, atmospheric impacts have been observed, including increased rainfall over the central Pacific, which classifies this as an El Niño event nonetheless.

Given the current weak status of this event, the CPC notes that “widespread or significant global impacts are not anticipated” this spring and summer. This time of year, ENSO’s impacts on North Carolina are often more muted anyway since the jet stream is weaker and has less effect on our weather, especially our summertime precipitation.

So for now, we’re not likely to see a major weather pattern change just because El Niño conditions are in place. We will continue monitoring these conditions during the spring, because if a stronger El Niño event emerges, it’s more likely to stick around until next winter.

What can we expect this spring? The CPC’s guidance suggests above-normal precipitation across the Southeast, which is typical of a warm-phase PDO event. Their three-month temperature forecast shows continuing warm conditions over the western US — also typical of a warm-phase PDO pattern — but equal chances of above-, near-, or below-normal temperatures over North Carolina.