The sights and stories that slowly trickled out of western North Carolina last September were so shocking, they were at times hard to believe.

Swollen rivers practically wiped out charming mountain towns such as Chimney Rock, Lake Lure, and Swannanoa. The death toll climbed across Buncombe County as search and rescue teams surveyed areas hit by flooding and landslides. Major dams were on the brink of failure.

As the devastation became evident, so did a foregone conclusion about the storm, which was confirmed in the weeks that followed: Helene was the worst.

As in, the worst tropical storm we’d ever seen in North Carolina. Indeed, during the cleanup and recovery process, Helene claimed two unfortunate records, becoming our state’s deadliest and costliest known storm.

North Carolina’s deadliest known tropical storms, as of September 2025

| Rank | Storm | Year | Fatalities in NC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hurricane Helene | 2024 | 108 |

| 2 | Charleston Hurricane | 1916 | at least 80 |

| 3 | Bahamas-North Carolina Hurricane | 1883 | 53 |

| 4 | Hurricane Floyd | 1999 | 52 |

| 5 | Hurricane Florence | 2018 | 45 |

| 6 | Great Beaufort Hurricane | 1879 | up to 46† |

| 7 | Hurricane Matthew | 2016 | 29 |

| 8 | South Carolina Hurricane | 1940 | at least 26 |

| 9 | Hurricane Fran | 1996 | 24 |

| 10 | Hurricane San Ciriaco | 1899 | 20 to 25 |

While a check of those lists shows Helene in the top spots, a closer inspection reveals that it’s far from the only recent storm to have caused extensive damage and a tragic loss of life.

In fact, those top ten lists look very different today than the last time we updated them exactly ten years ago – before our recent stormy era including the likes of Matthew, Florence, Dorian, and Helene.

One year after Helene, we revisit that storm with new perspectives about the impactful tropical storms over the past decade – first from the transportation sector, then for communities in western North Carolina. We also look at Helene’s impacts to towns and roadways, dig into new research about flooding events in our state, and paint an updated picture of the most damaging storms across North Carolina.

North Carolina’s costliest tropical storms by inflation-adjusted damage, as of September 2025

| Rank | Storm | Year | Damage (unadjusted) | Damage (2025 dollars) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hurricane Helene | 2024 | $59.6 billion | $61.2 billion |

| 2 | Hurricane Florence | 2018 | $17 billion | $21.8 billion |

| 3 | Hurricane Floyd | 1999 | $6 billion | $11.6 billion |

| 4 | Hurricane Matthew | 2016 | $4.8 billion | $6.4 billion |

| 5 | Hurricane Fran | 1996 | $2.4 billion | $4.9 billion |

| 6 | Hurricane Hugo | 1989 | $1 billion | $2.6 billion |

| 7 | Hurricane Irene | 2011 | $1.2 billion | $1.7 billion |

| 8 | Hurricane Hazel | 1954 | $136 million | $1.6 billion |

| 9 | Hurricane Dorian | 2019 | $1.2 billion† | $1.5 billion |

| 10 | Hurricane Ione | 1955 | $88 million | $1.0 billion |

A Damaging Decade for Roads

Perhaps no part of our state bears more scars from our recent stormy era than our roadway network. And while some roads can flood even in non-tropical storms – see Highway 12 along the Outer Banks for a frequent example – the scale of the impacts to our transportation infrastructure has been significant over the past decade.

The engineers in the Hydraulics Unit at the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) are responsible for the monitoring, stormwater management, and design of our state’s roadway network, and they’ve confronted this spate of storms first-hand.

Matt Lauffer, the State Hydraulics Engineer at NCDOT, recalled the first sign of something big happening in October 2016.

“What really kicked it off was Matthew, when we had 800 pipes washed out,” said Lauffer. “I remember responding and thinking, ‘I bet this is the event of a career.’”

But less than two years later, Matthew’s flooding and damage was surpassed in much of the Sandhills and southern Coastal Plain by an even wetter and longer-lasting event.

“Then we got Florence and that put Interstate 40 and Interstate 95 underwater for a week, and Wilmington was completely cut off,” he added. “That was the turning point to getting a better operational understanding into where the storms are causing flooding, and how.”

Over the past seven years since Florence, NCDOT has developed a comprehensive suite of monitoring tools to help them predict and track impacts to our infrastructure assets during storm events.

Working with NC Emergency Management, they developed a version of the Flood Inundation Mapping Alert Network (FIMAN) tool specifically for transportation, using a highly detailed lidar-measured elevation map of the state’s roadway network.

A separate tool called BridgeWatch tracks data and sends alerts for more than 15,000 structures, including culverts and bridges, across the state and around the clock.

And the Transportation Surge Analysis Prediction Program uses storm surge forecasts to predict inundation on coastal roadways.

Those tools proved their value during recent storm events, including during Hurricane Dorian in 2019 as they offered accurate forecasts for soundside flooding in Ocracoke and Oriental, along with Tropical Storm Debby last summer, when NCDOT’s operations staff monitored flood-prone stretches of Interstate 95 and US Highway 74.

But each of those eastern events was just a dry run – proverbially speaking – for western North Carolina’s wettest storm on record.

Fresh Flooding Concerns in Communities

Given its distance from the sea, our western region has historically been an infrequent target for impactful hurricanes, with many decades separating milestone storms like the July 1916 event that flooded the Asheville area and the August 1940 storm in the northern Mountains.

That affected the way locals thought about those sorts of events.

“The idea of flooding from hurricanes wasn’t even in our mindset,” said Zeb Smathers, who grew up in and is now the mayor of Canton in Haywood County.

That perception began to shift in September 2004, when a trio of remnant storms including Frances and Ivan caused flooding and landslides across our mountain landscape. But the bigger wakeup call, especially for the small town of Canton along the Pigeon River, happened more recently during our statewide stormy stretch.

In August 2021, a weekend of slow-moving showers across southern Haywood County preceded a soaking from the remnants of Tropical Storm Fred. With more than 20 inches of total rainfall in upstream areas over a 60-hour period, the Pigeon River surged and sent a wall of water through Canton and other riverside towns.

“That was sort of a freakish, demonic flash flood event,” recalled Smathers.

During Fred, areas along the river including Canton were under a Flash Flood Emergency – a rare version of a Flash Flood Warning used when life-threatening flooding is expected.

That warning was not overblown, as Fred’s flooding caused six fatalities in Haywood County, along with more than 900 buildings and 20 bridges either damaged or destroyed.

Determined not to let history repeat itself, the county used lessons learned from Fred to get a head start in preparing for the next flood event – whenever it might occur.

That included taking an inventory of homes to make it easier to share future warnings with residents, configuring emergency satellite internet access, purchasing flood alert sirens using grant funding from the NC Department of Public Safety, and undertaking a streambank restoration and debris removal project along the Pigeon River. The latter had public safety benefits beyond just flood protection.

“We got a lot of debris out of the river so it’s not like missiles aimed at you during a storm,” said Smathers.

Even with those measures in place after Fred, it was hard to anticipate the magnitude of our next mountain flood event only three years later.

Helene’s Heavy Impacts

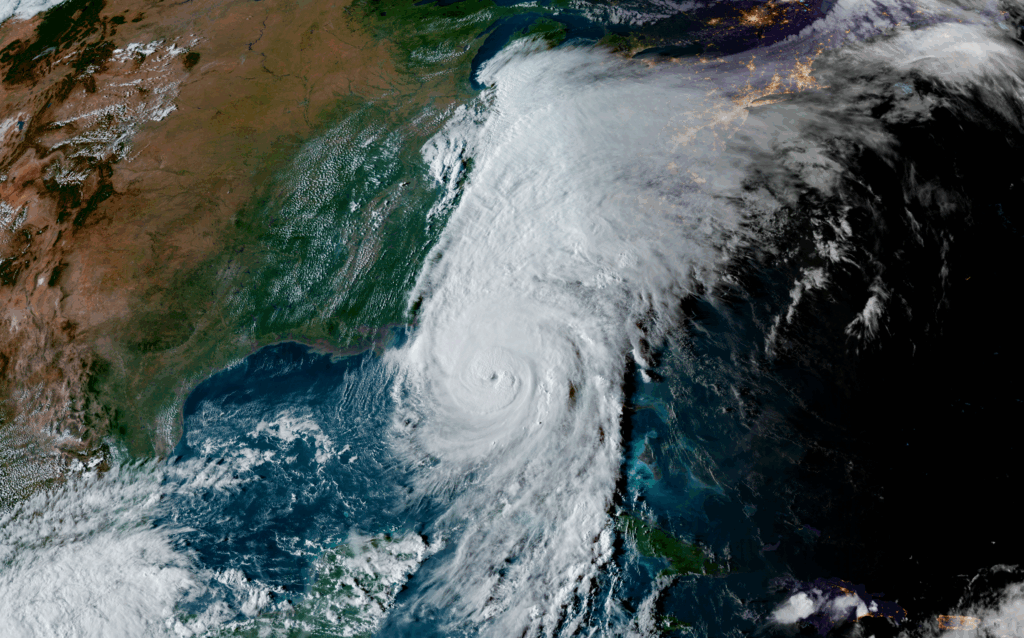

The earliest indications of an approaching storm last September appeared several days before Helene even had a name. Initially a tropical disturbance tracking northward in the Caribbean Sea, model forecasts showed good agreement on a trajectory bringing it over or near western North Carolina.

“We saw this storm coming. My mayor Spidey-sense went off, and we went from there,” said Smathers. “I made my first phone call to our town and county managers on Sunday, and Helene hit on Friday.”

During that five-day lead-up to Helene’s arrival, there were more phone calls, including one for Smathers with the governor and attorney general on Tuesday. There were further preparations, spurred on by messaging from the National Hurricane Center that warned of possible landslides and major river flooding. Then there were the first signs of flooding, well before Helene had arrived in earnest.

On Wednesday, September 25, a cold front had set up across the southern Appalachians, fed by tropical moisture from the fringes of Helene’s broad circulation. By Thursday morning, more than six inches of rain had already fallen across much of the region, raising rivers and bringing an initial wave of flooding around Asheville.

That scene of heavy rain before the main event began was all too familiar for Smathers, who feared a repeat of Fred on a much broader scale.

“It was a perfect storm in a perfect storm,” he said. “I was worried this time that there would be multiple Cantons across western North Carolina, and that’s exactly what happened.”

The rain continued to pour as Helene’s outer rain bands moved in. All the while, the storm had reached Category-4 strength to our south over a record-warm Gulf of Mexico and with little environmental interference, such as wind shear or dry air hindering its development.

Less than 12 hours after it made landfall along the Florida panhandle, Helene’s remnant eye was over western North Carolina. That meant its winds still packed a punch, with gusts clocked at up to 106 miles per hour on Mount Mitchell.

And the rain kept falling through Friday morning, yielding storm totals of more than 12 inches along the Blue Ridge – and as much as 30 inches in southern Yancey County – that shattered records across the region.

This put portions of 21 counties in Flash Flood Emergency warnings: a realization of Smathers’ fears about multiple Cantons, and a confirmation of the forceful public messaging from the National Weather Service that warned of “catastrophic flooding” and “one of the most significant weather events… in the modern era.”

The Pigeon River at Canton again sustained a heavy hit, surpassing its historical highest crest from Hurricane Ivan by more than four feet. In Haywood County, there were five lives lost during the storm. And it was personal for Smathers; “my sister lost her house in 2021, and she lost it again in Helene,” he said.

Despite the severity of the damage from Helene, Smathers credits the post-Fred preparations with helping his town bounce back faster this time around.

“We love our high school football here. We lost our field for an entire year after Fred. We got it back after three weeks this time because of the debris removal,” he said, noting that there was little gouging on the turf with less debris spilling out of the river.

And a year later, “we have businesses that are open or about to open,” he added.

Of course, that’s not true for all mountain areas, especially those along the Broad and French Broad rivers. The mud and debris are now mostly gone in places like Marshall and Chimney Rock, and their downtown shops and restaurants began reopening this summer. But some key businesses, including the main grocery store serving Swannanoa, have yet to return.

Local utilities – for which the Office of State Budget and Management estimated damages of nearly $7 billion – are still being repaired or rebuilt, including the wastewater treatment plants in Hot Springs and Spruce Pine.

And while 95% of public roads are now fully reopened, our roadway network also tells the story of just how bad the damage was, and how much work is left to be done.

Roadway Response and Recovery

During the storm last September, the engineers from NCDOT’s Hydraulics Unit monitored the situation from the state Emergency Operations Center in Raleigh. The network of new gauges, sensors, and tools added in the wake of Matthew and Florence helped them track the developing impacts in the western part of the state.

“We had areas showing in our FIMAN tool as being above the 500-year event,” said Kurt Golembesky, an engineer with NCDOT’s Highway Floodplain Program.

Those areas included sections of Interstate 40 leading into Asheville, which models showed being flooded by the rising rivers.

“Upstream, we had the Asheville gauge at the River Arts District, which is a forecast point, so we could see that forecast showing the rise every hour and track when that water would reach I-40,” he said. “We had to scratch our heads and ask if this is really true. We trusted our forecast and we trusted our modeling.”

As in Dorian along the coast, the roadway inundation forecast was spot on for these western sites during Helene, allowing NCDOT to identify and close stretches of Interstate 40 before they flooded.

In other areas, the nature of Helene’s damage to our roads was very different from what NCDOT dealt with during the big storms in eastern North Carolina. Instead of floodwaters spreading out across a wide area, rushing over roadways and through the culverts beneath them, the mountainous terrain channeled that water into powerful bursts that knocked out sensitive structures.

“In most events out east, you lose pipes but not many bridges,” said Andy Jordan, the State Hydraulics Operations Engineer at NCDOT. “In Florence, we lost maybe five bridges. In Helene, we lost 150.”

One of the most notable sections of road that washed out during Helene was Interstate 40 through the Pigeon River Gorge at the Tennessee border. A combination of flooding from the river below and mudslides from the mountainsides above caused that road to crumble.

“It wasn’t just a water event. It was a geologic event,” said Lauffer. “The number of debris flows, the amount of material that came down those canyons, the sediment material that ended up in the rivers. It’s hard to describe the magnitude of the damage.”

Just as they did in redesigning Interstate 95 through Lumberton after Matthew or elevating Highway 421 into Wilmington after Florence, NCDOT has had to innovate to ensure our rebuilt roads and bridges in western North Carolina will better withstand another event of this caliber.

“From a hydraulics perspective, we’re implementing modeling to understand where these hydraulic forces occur, where we need to put rock, and inform the geotech engineers and build more stable systems back,” said Lauffer.

“That system will be protected from another Helene event, if not more with the structures we’re going to put in.”

A New Era of Flood Events

While there are plenty of questions even one year after Helene – about funding sources to support rebuilding, about timelines for further reopening, and about the future fire seasons in storm-damaged areas – one thing has become certain.

“Tropical cyclone flooding isn’t just a coastal issue. It has impacts and damages further inland,” said Helena Garcia, a PhD candidate in the Environment, Ecology, and Energy Program (E3P) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Her latest research, published this summer, highlights the risks of repetitive flood events in central and eastern North Carolina. Using a machine learning model trained on flood insurance claims and policies, Garcia created high-resolution maps of flood extents for 78 events – including 44 tropical storms – between 1996 and 2020.

She found that 43% of flooded buildings over that time were located outside of traditional floodplains, in areas where historical flood events weren’t as common and where flood insurance coverage is much lower. While her study did not include recent storms such as Helene and Chantal, those events offer further confirmation of her findings.

“Just because you’re not in a flood zone, it doesn’t mean you have zero flood risk,” said Garcia. “After Helene reached so far inland, it has reawakened that idea for people.”

Smathers has seen the manifestation of that increased risk from tropical systems, even far from the coastline.

“In the last 20 years, Canton and Haywood County were more impacted than Charleston, SC,” he said. ”I sleep with one eye open during hurricane season.”

Another key takeaway from Garcia’s research is that among buildings that flooded during her 25-year period of interest, 23% flooded more than once. For those areas, the average return period between flood events was 9.6 years, but in a quarter of cases, a second flood happened within three years.

That statistic will surely resonate with residents on either end of the state: in the east after back-to-back hits from Matthew and Florence in 2016 and 2018, and in western areas like Canton after Fred and Helene.

“During Fred, we were told this was a once-in-a-lifetime storm, and then we saw a repeat on a wider scale three years later,” said Smathers.

Garcia’s research, and our spate of recent soaking storms beginning with Hurricane Floyd in 1999, have also dispelled the myth that only high-value, well-insured beachfront homes need to worry about flooding from tropical events.

“There’s a huge disparity in who floods and how that can shape their recovery trajectories,” she said. “A lot of lower property value housing ends up in floodplain areas just because it’s cheaper, and those people are more vulnerable already.”

Noting both the widespread flooding in western North Carolina during Helene and this summer’s floods from Chantal in places like Chapel Hill and Mebane, Smathers offered an experience-informed caution to people across the state.

“If your community has not been impacted by a water-related event, especially flooding, it will be,” he said. “If you are near water, you better have that mindset.”

The growing prevalence of flood events has redefined damaging storms in North Carolina and inspired new actions to prepare for what comes next.

Our Worst Storms Statewide

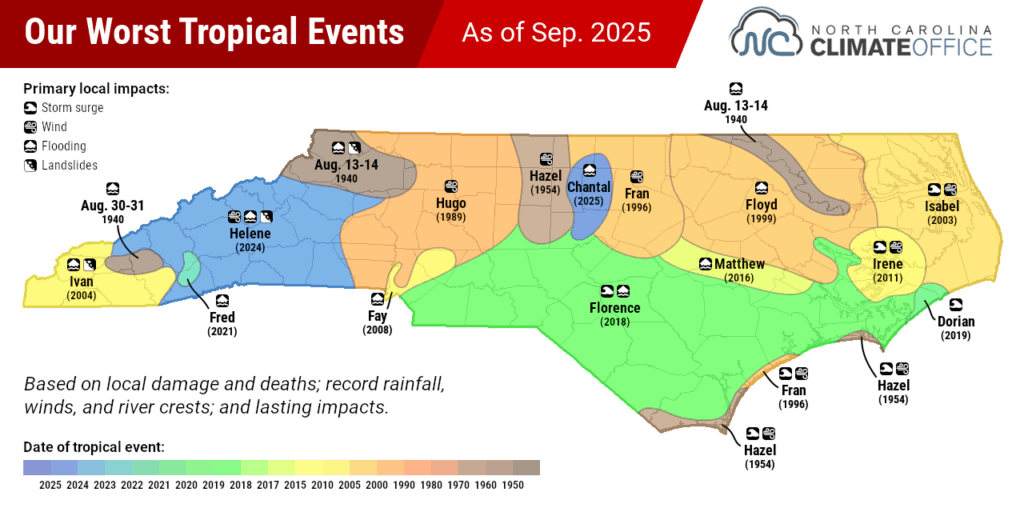

The current map of North Carolina’s worst tropical storms – defined as the most damaging storm based on local impacts; fatalities; and record winds, rainfall, and river crests – looks very different from the one we produced ten years ago.

For one, Helene made us take a more nuanced look at historical inland flooding events. That put a few of those events on the map, including a pair of August 1940 storms that caused heavy rain and landslides in the northern Mountains, record flooding downstream along the Roanoke River, and devastation in southern Mountain towns such as Sylva.

Of course, we also factored in the newer storms. In all, six tropical storms in the past ten years feature on this map. They’re considered the worst storm for all or part of more than half of the state’s 100 counties, reflecting the widespread impacts of events including Florence and Helene, and how they exceeded anything those areas had seen historically.

“Ivan was the record-holder until Helene, Frances and Fred were similar, and Helene topped them all,” said Smathers of the storms affecting Canton.

Along with being our clear-cut costliest storm, with estimated damages of $59.6 billion more than triple Florence’s official assessment of $17 billion, Helene has become the costliest for NCDOT as well. Their data shows Helene’s estimated damage to our transportation sector was $5 billion, while all previous storms between 2002 and 2024 had a total expenditure of $1.5 billion.

That combination of impactful recent events has added up to more than just costs.

“It has affected our operations,” said Lauffer. “We have a lot more drainage complaints from our operations staff due to the frequent occurrence and magnitude of these storms.”

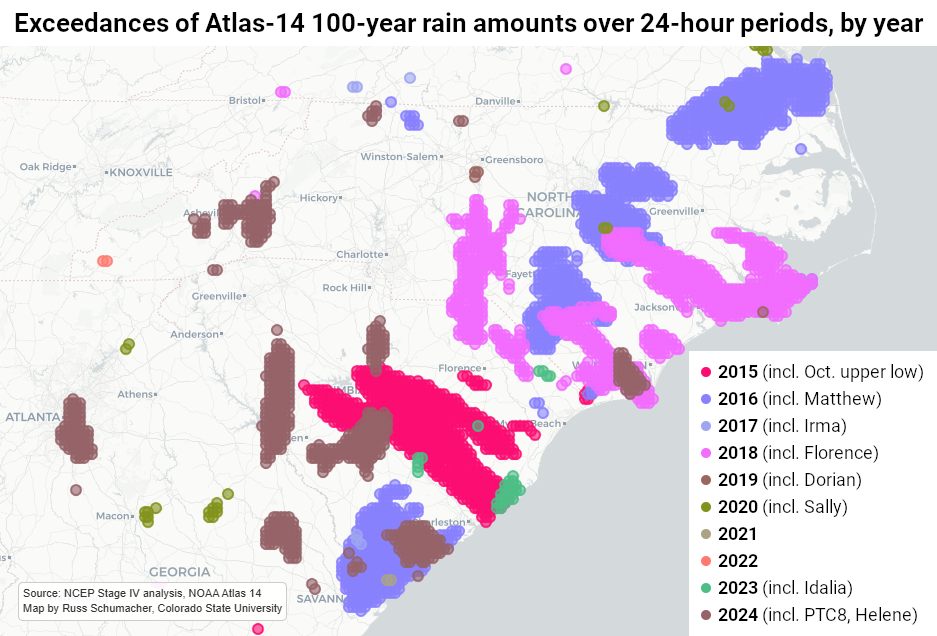

One way of seeing that is through exceedances of so-called 100-year rain events — better stated as storms with a 1-in-100 chance of happening in any given year based on historical rainfall data from NOAA’s Atlas 14 product.

Beginning with the upper-level system fed by moisture from Hurricane Joaquin in early October 2015, much of the Carolinas has seen events of this magnitude just over the past decade – and this map doesn’t even include Chantal, which was worse than a 1-in-100-year event in parts of the Piedmont.

We know that storms like this are becoming more common, and climate change is a contributor, boosting sea surface temperatures and intensification rates, allowing storms to pull in more moisture, and increasingly stalling out these storms — including in the Carolinas — once they reach land.

That emphasizes the need for better preparedness – and better communications about these risks – in all areas.

“Communication about flooding in the US paints a binary risk, but anywhere it rains, it can flood,” said Garcia, whose study notes that a significant portion of recent flooding in North Carolina has occurred in places historically considered low-risk.

“We all focus on the coastal areas, but it needs to be a comprehensive approach across the state since flooding can happen everywhere.”

For NCDOT, whose roads do run everywhere, one key to responding to recent storms and preparing for the challenges of the future has been their partnerships with other groups. That includes working with NC Emergency Management on the lidar mapping of roadways and the incorporation of that data in other tools.

“That’s huge because that allows us to do the vulnerability assessment and the modeling of flooding in our area,” said Lauffer. “What are our redundant routes? How do we make our system more robust? Those things are a lot more in our vocabulary now.”

He added that NCDOT works closely with DEQ and the State Resilience Office for future planning, along with the State Climate Office on precipitation monitoring and projections, as in our RaInDROP tool showing changes in 100-year and other extreme rainfall events.

Partnerships with the National Weather Service’s river forecast centers have provided more forecast data points, like the ones from Asheville that prompted the closing of Interstate 40 before it flooded during Helene.

NCDOT has also worked with the US Forest Service since the storm to locate material from a quarry in the Pisgah National Forest that’s being used to bolster the in-construction section of I-40 along the Tennessee border, which is expected to fully reopen by 2028.

That work is driven by a meaningful motivation that became evident over the past 12 months in western North Carolina, just as it was in other parts of the state during the stormy past decade.

“The thing that I think is most impressive about Helene is the resilience of the people and how they respond to these disasters,” said Lauffer. “When you’re riding down those corridors that have been destroyed and you see those communities coming together, the way people respond to help each other after a disaster is really encouraging.”

“That also drives us as engineers to think about how we can minimize that impact on those people in the future.”

It’s the sort of forethought that will absolutely be necessary as our damaging storms keep getting worse and impacts increasingly reach areas that were historically at lower risk from tropical storm flooding.

A year ago, we saw that manifest in the Mountains as Hurricane Helene made its mark as the worst storm our state has ever seen.