This is the fifth post in our “Stormy Summer” series looking back at some memorable hurricane anniversaries occurring in 2019.

Long after their hurricane-force winds had worn off and they left Florida in varying degrees of disrepair, three storms in September 2004 moved up the east coast and showed they weren’t done dealing damage just yet.

The remnants of Frances, Ivan, and Jeanne all crossed the Carolinas over the span of three weeks, causing flooding, landslides, and the wettest month ever in the western part of our state.

In that stormy summer 15 years ago, there were 15 named storms in the Atlantic, seven of which affected North Carolina in some way. In August alone, Alex grazed the Outer Banks as a Category-2, while the remnants of Bonnie, Charley, and Gaston also moved up the Coastal Plain.

But the three storms in the western part of the state were the most damaging, in part because of their individual impacts but also because of the collective ones. Excess moisture had nowhere to go between storms, and on the mountain slopes, what falls from up above must come down — to rivers, towns, and roads dotting the terrain.

Hurricane Frances

The first of the three systems to develop was Frances, which became a tropical storm midway across the Atlantic on August 25 and was a major hurricane just two days later.

Frances reached Florida’s southern coast on September 5 at Category-2 strength. After crossing the peninsula, Frances moved over the Gulf of Mexico as a tropical storm but did not restrengthen before hitting the panhandle.

By then, Frances was headed due north, traveling around the periphery of an upper-level high pressure system off the Southeast coast. It was a pattern that held for much of the month, meaning storms traveling along that conveyor belt tended to follow a similar track.

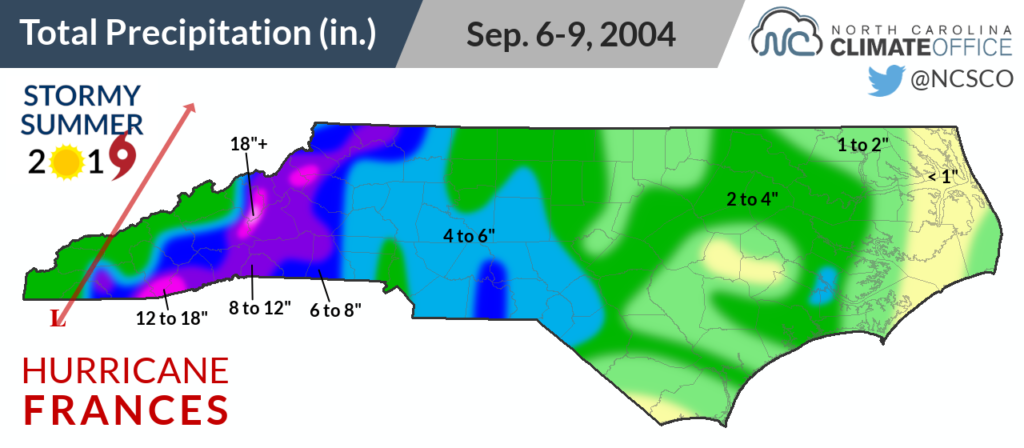

After its second US landfall, Frances weakened to a tropical depression as it moved through Georgia and over far western North Carolina, but with an assist from the local terrain, the storm’s remnants were still capable of causing widespread flooding.

Air rising up south-facing slopes produced some extreme precipitation totals over a short time period. Mount Mitchell received 23.57 inches over four days, including 16.50 inches on September 8 — the greatest single-day total on record at that site.

Along with a 14.62-inch storm total at Black Mountain, the rain over the Swannanoa River basin caused downstream flooding in the Asheville area.

A torrent of water rushing through the North Fork Reservoir washed out a pipeline to the city and cut off the drinking water supply, while up to five feet of flooding hit homes and businesses.

A number of debris flows were triggered by wet weather weakening embankments, including one on the Blue Ridge Parkway near Mount Mitchell and a rockslide on Interstate 40 east of Asheville.

Only one week into the month, the Mountains had already had a historic, memorable storm. Another one that would bring even more water was lurking just around the corner.

Hurricane Ivan

As Frances was headed out of North Carolina on September 8, Hurricane Ivan was nearing Category-5 status over the Caribbean Sea. It was farther south than Frances had been, but still bound for a similar destination.

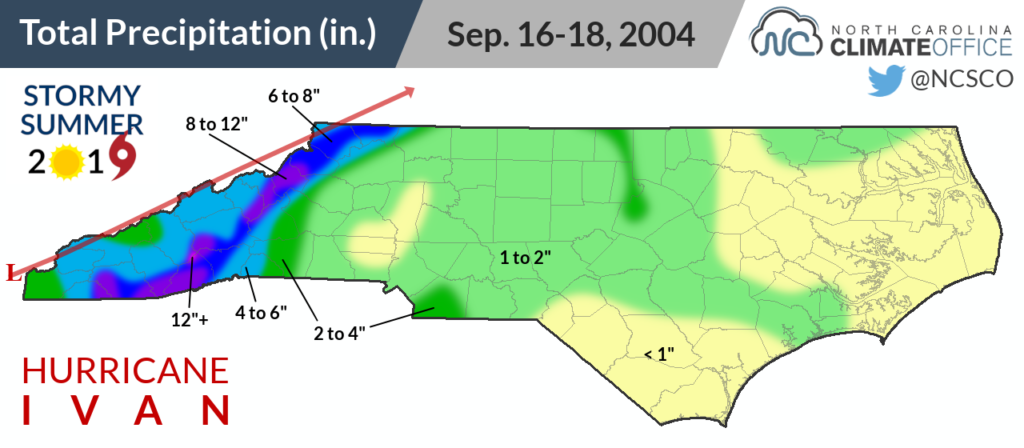

Ivan was a Category-3 at landfall near Mobile, AL, but its remnants turned northeastward — again along the western edge of the upper-level ridge — to track along the North Carolina-Tennessee border on September 17.

The greatest rainfall totals came across the southern Mountains, with up to 17 inches at Cruso in Haywood County. Overall, amounts in western North Carolina were generally between 6 to 10 inches, although distinguishing the effects of Ivan’s precipitation compared to Frances’ was mostly academic since such little time passed between the two storms.

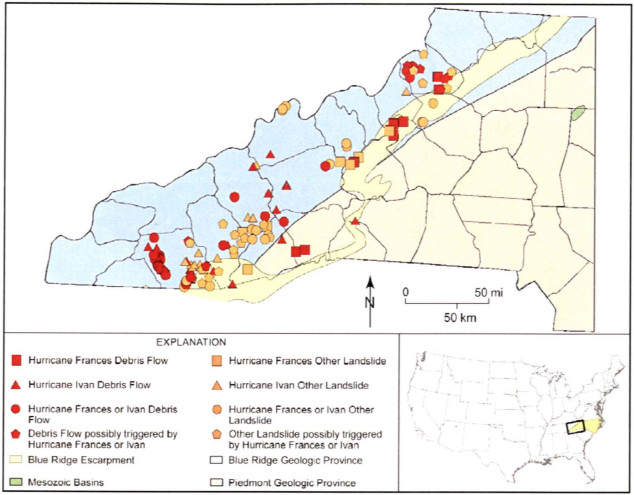

The waterlogged soils could hardly handle the additional moisture, finishing the job Frances had started in causing landslides and debris flows. There were about 400 reported between the two storms in North Carolina.

The most significant — and the most deadly — occurred in southeastern Macon County. A debris flow on Fishhawk Mountain rushed 2,200 feet downhill, carrying several feet of mud and 16-ton boulders at speeds of more than 30 mph. When it reached the Peeks Creek community in the valley below, it destroyed 15 homes and killed five people.

Trees and power lines in the rain-weakened ground were easily toppled by Ivan’s gusty winds, knocking out power to nearly 85,000 Progress Energy customers in western North Carolina.

Elsewhere in the state, the Gulf moisture Ivan brought in fueled severe thunderstorms that spawned four tornadoes. Along with the 13 tornadoes from Frances and the seven from Jeanne as far east as Martin County, every region of the state felt some effects from these three storms.

Hurricane Jeanne

The third and final storm of the month thankfully had the lightest impact in North Carolina, but as Hurricane Jeanne looped east of the Bahamas, it taunted the storm-weary southeast coast and raised fears of what even more rainfall might do.

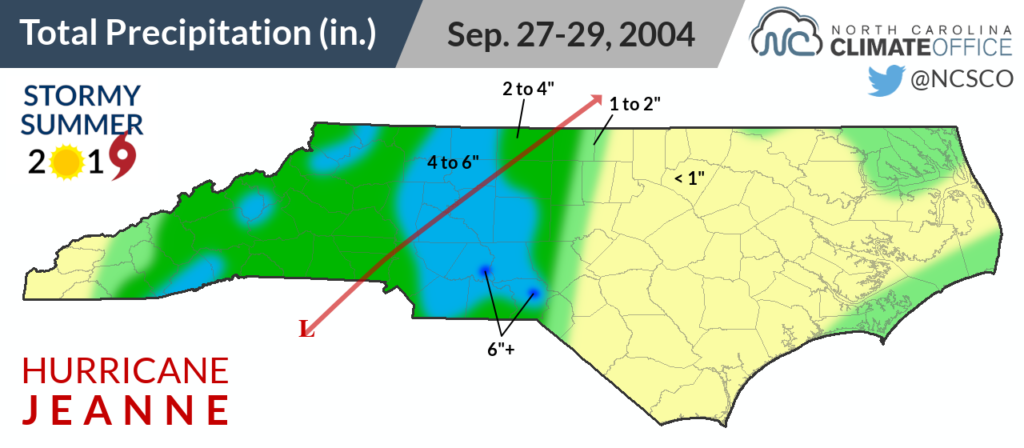

The week it spent slowly drifting over open ocean may have been a blessing for western North Carolina. That extra time allowed water levels to drop, and even though Jeanne’s remnants arrived only 11 days after Ivan’s, it didn’t crest rivers to the same heights as the previous two storms.

It also helped that Jeanne didn’t bring as much rain. Its track stayed farther east as it crossed Georgia and the Carolinas, and totals were generally lower, with 5.73 inches on Mount Mitchell and 5.48 inches at Clear Creek in Henderson County.

Only minor flooding was reported from Jeanne, but it did add even more rain to what was a record-setting month.

Lake Toxaway finished September 2004 with 31.45 inches of rain — not just the wettest September on record, but the wettest month on record there. Dating back to 1950, two of its three wettest days — 14.41 inches on September 8 and 10.02 inches on September 17 — occurred that month.

Mount Mitchell had a monthly total of 46.77 inches, meaning nearly two-thirds of its annual average precipitation total (74.16 inches) fell in a single month in September 2004.

Even after our storms since then, that monthly total remains the wettest on record at Mount Mitchell, more than twice the amount from the next-wettest month in July 2013 (22.15 inches) and even exceeding Florence-affected September 2018, in which the state’s highest point received 20.70 inches.

Despite avoiding the worst of the flooding, the northern Mountains also had extreme rainfall during the three events, which totaled 23.01 inches in Boone — the wettest month on record at that site as well.

In that part of the state, the storms of 2004 conjured up memories of 1940, when the remnants of an August hurricane lingered over the Mountains, dropping more than a foot of rain and causing more than 2,000 landslides and 14 deaths in Watauga County alone.

A Month to Remember

With events like those in August 1940 and even July 1916 in our record books, it was clear in 2004 that heavy rain and flooding was a risk in the Mountains. But the three storms that September highlighted their impacts to our modern-day landscape, peppered with impervious surfaces and structures that had never been tested in such a scenario.

One of the first such impacts felt during Frances was to the almost-overflowing North Fork Reservoir. The summer of 2004 had already been a wet one in the Asheville area — the 21st-wettest since 1889.

When the first September storm arrived, there was little room to accommodate its rainfall. That forced spillway gates to be opened, which likely made the downstream floods a few inches deeper than they otherwise would have been.

Since then, the city of Asheville has kept reservoir levels lower during hurricane season as a precautionary measure.

If Frances’ flood waters were a wake-up call, then Ivan’s were a call to action.

In 2005, the state legislature passed the Hurricane Recovery Act, which instructed the North Carolina Geological Survey to create landslide hazard maps for 19 western counties.

City ordinances passed in Asheville now require new construction to be built at least two feet above the base flood elevation, and some properties in the floodplain have been bought out.

Like at the coast after Hurricane Floyd in 1999, home and business owners in western North Carolina learned the importance of knowing their location relative to the floodplain, and of having flood insurance to cover them in a rare but distinctly possible repeat of September 2004.

All in all, that month was a rude reckoning with the difference between weather and climate.

Tropical storms are a part of North Carolina’s climate, even in the Mountains, which typically receive about 9% of their warm-season precipitation from hurricanes or their remnants, according to a study our office conducted using data from 1981 to 2009.

In 2004, that tropical precipitation contribution was nearly six times the normal amount due to the prevailing weather pattern and a string of storms destined to find higher ground.

As a result, September 2004 has now become one of those historical months remembered for the rain that wouldn’t stop coming down, and for the earth that moved with it.

Sources:

- Tropical Cyclone Report – Hurricane Frances by John L. Beven II, National Hurricane Center

- Tropical Cyclone Report – Hurricane Ivan by Stacy R. Stewart, National Hurricane Center

- Tropical Cyclone Report – Hurricane Jeanne by Miles B. Lawrence and Hugh D. Cobb, National Hurricane Center

- Landslide Events, Hurricanes Frances and Ivan from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality

- Hurricane Ivan Situation Report #4 from the US Department of Energy

- The Deadly Debris Flow in Macon County NC During Hurricane Ivan by Jonathan R. Lamb, National Weather Service Greer, SC

- Frequency and Magnitude of Selected Historical Landslide Events in the Southern Appalachian Highlands of North Carolina and Virginia by Richard M. Wooten , Anne C. Witt , Chelcy F. Miniat , Tristram C. Hales , and Jennifer L. Aldred

- From the archives: Impact of Frances, Ivan lingers years later by John Boyle, Asheville Citizen Times

- Steps taken to reduce flood risk in Asheville after 2004 floods by News 13 WLOS

- Geologic Hazards Assessment Plan Revision, Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests by Thomas K. Collins, USGS Forest Service