In North Carolina, it was a winter of warmth with a month of cool, snowy weather stuck in the middle. So what shaped our weather over the past 3 months, what do the statistics show across the state, and what can we expect as we enter the spring?

Our Winter Patterns

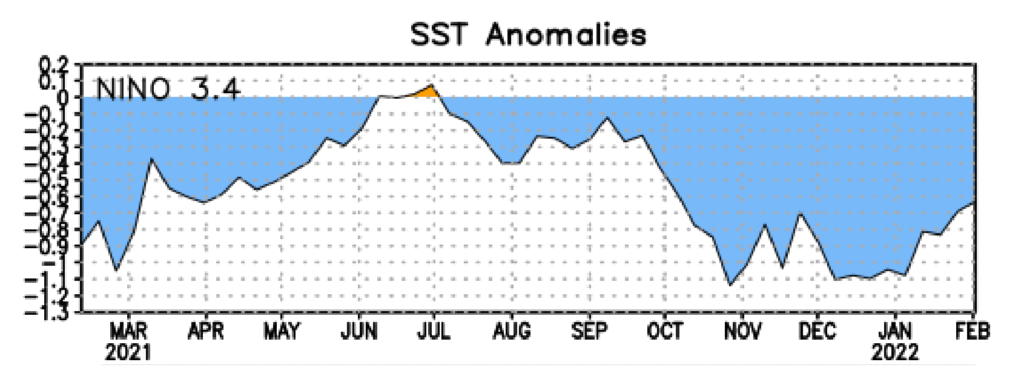

In our winter outlook from November, we noted a moderate La Niña event had developed for the second year in a row. That pattern often sees a weakening and northward shift of the jet stream, leading to warmer and drier conditions across the Southeast US, including North Carolina.

Our expectations for this winter balanced those typical impacts – often amplified in the second half of a back-to-back or “double-dip” event – with our decidedly un-La Niña-like winter in 2020-21, which was wetter than normal.

Ultimately, this winter does show many of La Niña’s fingerprints, but also a notable divergence from that pattern during our most wintry weeks.

December was exceptionally warm across the southern and eastern US, including the 2nd-warmest on record in North Carolina. It was also a dry month in the Carolinas and mid-Atlantic, with wetter conditions to our north across the Ohio Valley in a classic La Niña precipitation pattern.

While La Niña held steady through mid-winter, a change in the large-scale patterns closer to home caused a big shift in our January weather. Beginning with our sudden cool-down on January 3, the polar jet stream dipped southward, suppressing warmer air to our south while cold air rushed in from the north.

With that setup in place, the storm track also shifted southward, which allowed for regular precipitation in both liquid and frozen forms. That included four snow events in a four-week period in the Triad for the first time since January 2000.

The final atmospheric battle in our wintertime tug of war came in February as the subtropical jet stream lifted back across the eastern US, leaving us generally warmer. While a number of cold fronts moved in from the west, most dried out as they crossed the Mountains, putting the Piedmont and Coastal Plain in a drier pattern.

Seasonal Statistics

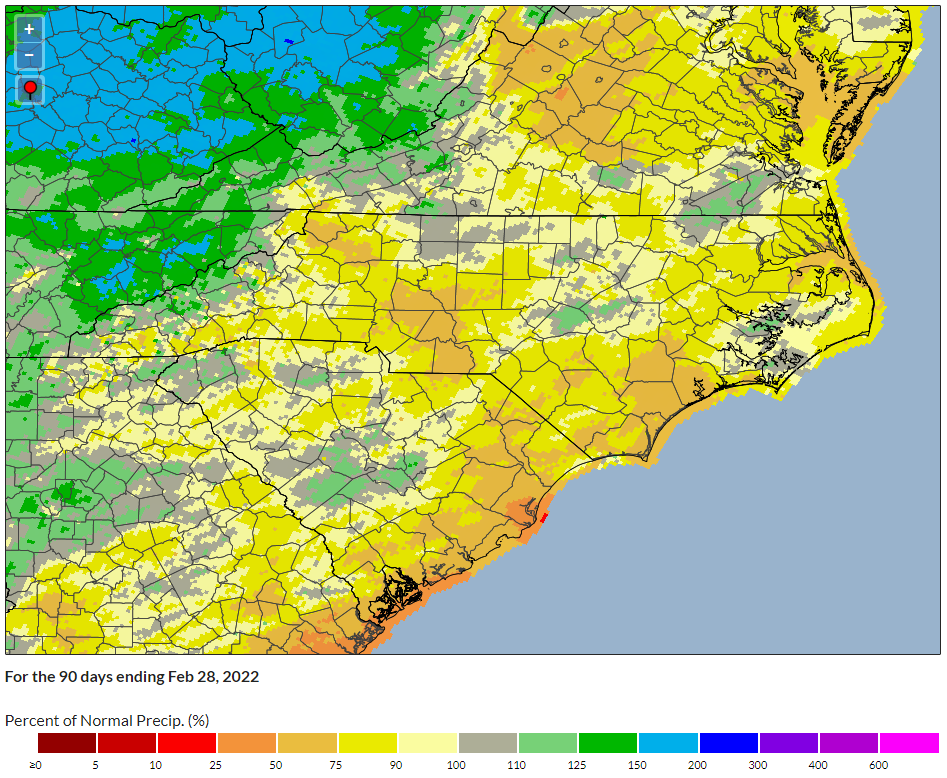

With two warm, dry months on either side of a cool and wet one, this winter averaged out to be warm and dry overall. According to the National Centers for Environmental Information, the three-month period from December 2021 to February 2022 ranks as our 15th-warmest and 33rd-driest winter since 1895.

The statewide average temperature of 45.0°F was 2.2°F above the 1991 to 2020 average. Five of our top fifteen warmest winters have happened in the last seven years.

The average precipitation of 9.53 inches was 1.62 inches below the recent 30-year average. It broke a streak of three consecutive wet winters, and was our driest winter since 2016-17.

In Charlotte, it ranked as the 9th-warmest winter dating back to 1878, and Greensboro had its 10th-warmest winter on record since 1903.

The Triad was also one of the the lone areas with at or above normal seasonal precipitation. Greensboro was 0.7 inches wetter than its winter normal, in part due to the liquid contribution of the 8.2 inches of snow there..

Elsewhere, precipitation departures ranged from barely below normal – like an 0.6-inch seasonal shortfall in Raleigh – to deficits of nearly 3 inches at the coast. Wilmington was 2.9 inches below normal and New Bern was 2.6 inches below normal, which was its 15th-driest winter since 1948.

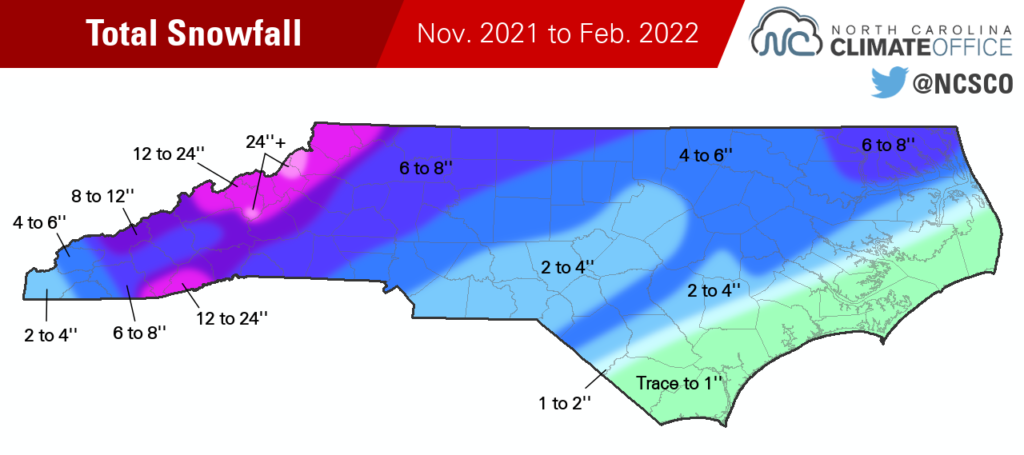

Snow totals varied widely across the state, even within our three regions. While the northern Coastal Plain had as much as 8 inches total, mostly from the January 21 event, the southern coast saw freezing rain that day and little to no snow accumulation for the season.

The southern and eastern Piedmont had less snow than northern and western areas such as the Triad, but it was still the snowiest winter in Charlotte since 2013-14, with 4.3 inches total. The 2.7 inches of snow in Raleigh was only about half of the 1991 to 2020 annual average of 5.2 inches, but it was the most in a winter there in three years.

With a total accumulation of 10.6 inches, Asheville barely exceeded its annual average of 10.3 inches, although the bulk of that came from a single event on January 16. Banner Elk totaled just over two feet – 24.3 inches – this winter, mostly from four events in January.

While that snowy January was a fruitful one for some areas, outside of that one wintry month, snow was hard to come by this winter. That’s most apparent at Mount Mitchell, our state’s highest point and climatological snowiest site. It averages 89.1 inches of snow per year, but received just 43.9 inches this winter – and no measurable snow in December or February.

Of course, it only takes one active month — or even a single event — to make for a snowy winter, even in a La Niña year. The winter of 2017-18 also ranked as warm and dry overall, but featured several wintry events in January. And winter in 1999-2000 was warm and dry as well, but quite memorable due to the succession of January snowstorms, including a 20-inch blizzard in Raleigh.

Because of a quirk of human consciousness that prioritizes a few impactful moments over several weeks of monotony, the winter of 2021-22 is likely to conjure up memories of those weekend winter storms in January, rather than the prevailing warmth that dominated the rest of the season.

Spring Outlook

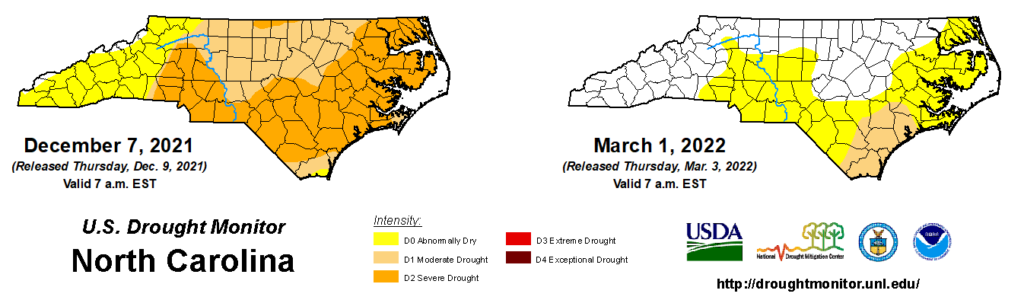

Even last November, some people across the state were already thinking ahead to the spring. Mired in a fall drought with the prospect of a dry winter ahead, concerns were growing that soil moisture might be insufficient for planting and wildfires would light up the landscape once warmer spring weather arrived.

At the time, we offered this more optimistic outlook:

Thanks to lower evaporation and irrigation demands, cool-season precipitation goes a long way in maintaining soil moisture, streams, and lake levels, so we could even tolerate a drier winter without significant degradation of drought conditions.

That wound up being the most spot-on sentence in our winter outlook. After a dry December, January’s precipitation brought widespread drought improvements, and the current US Drought Monitor shows most areas better off than they were entering the winter.

Soil moisture levels are generally at or above the 50th percentile and adequate for planting, with the lowest values in parts of the Sandhills and Coastal Plain where sandy soils can’t hold that moisture near the surface as effectively.

That recent dry weather across eastern North Carolina has rightfully rekindled concerns about drought, and the current ENSO outlook shows La Niña likely to persist through the spring. That doesn’t guarantee we’re headed deeper into drought, though.

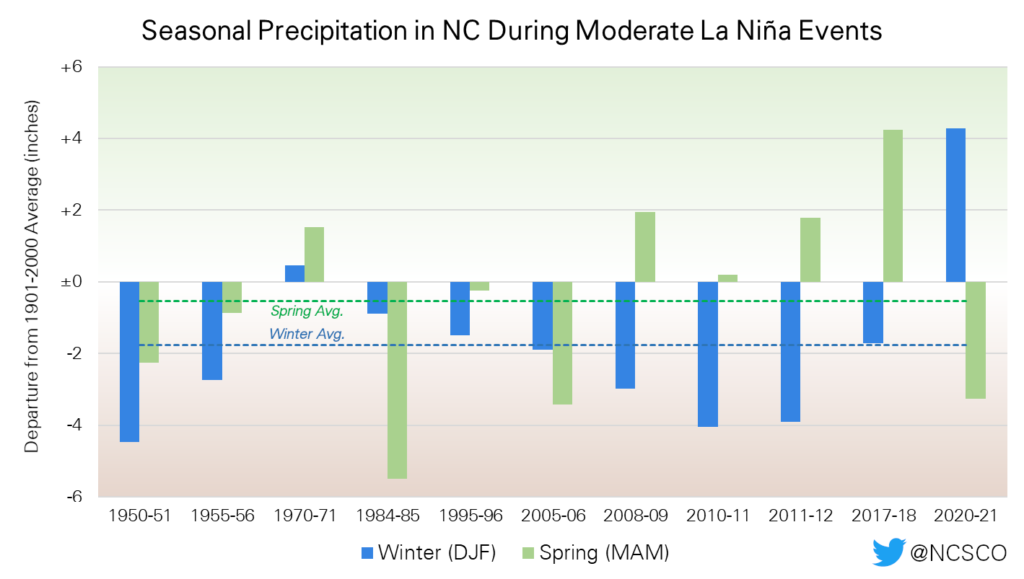

La Niña’s impacts on North Carolina tend to be less pronounced in the spring compared to the winter. Of the eleven moderate La Niña events since 1950, nine had dry winters but only six had below-average precipitation in the following spring.

Our average wintertime precipitation in those moderate La Niña events is 1.76 inches below the long-term 1901 to 2000 average, but that deficit shrinks to 0.53 inches in the spring.

The Climate Prediction Center’s outlook for March through May continues to show a 40 to 50% chance of above-normal temperatures across the southern tier of the US, but there is no strong signal toward either prevailing wet or dry conditions for most of North Carolina.

Given the recent dryness in some spots and the slightly dry signal associated with an ongoing La Niña, the National Interagency Fire Center is predicting above-normal significant wildland fire potential for North Carolina in April. That’s also our most common month for wildfires since warmer temperatures can quickly dry out vegetation, and some trees and have yet to fully leaf out or green up by that point.

If our recent pattern continues, with frontal passages from the west that dry out as they cross the Mountains, then drought could remain or expand in parts of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain. But even a few events with widespread rain could slow or reverse any degradation — and the forecast for the next week calls for multiple events totaling at least an inch and a half statewide.

All in all, we weathered the La Niña winter fairly well thanks to the recharge from January’s rain and snow. While we’re not out of the woods just yet, they’re not on fire either, as some feared last fall. We now hope for more March moisture and ample April showers so those May flowers — and crops — can emerge healthy and bright later this spring.