As we pass the midway point of March, if you’re left wondering “where was winter?!”, you’re not alone. A heavy dose of mild weather since mid-January made for a largely uneventful season, especially in terms of wintry precipitation.

However, such conditions were not entirely unexpected. In our Winter Outlook post released last November, we noted that La Niña conditions in place across the Pacific made last fall’s warm, dry pattern likely to continue. As we wrap up the winter, let’s take a closer look back at the winter by the numbers and total snowfall, the pre-season predictions, where conditions stand at the moment, and what might await us this spring.

Final Winter Stats

The wintertime average precipitation of 8.69 inches ranks as the 23rd-driest winter out of the past 122 years. That’s about two inches below our average winter precipitation from 1981 to 2010. The last winters that dry were in 2010-11 (7.62 inches) and 2011-12 (7.64 inches).

Perhaps more noticeable were our mild temperatures. For the three-month period from December through February, the statewide average temperature was 45.87°F, which is nearly 4 degrees above the 1981-2010 average. That ranks as North Carolina’s 6th-warmest winter since 1895, and the warmest since 1971-72. Most weather stations across the state had one of their top-ten warmest winters on record, and several long-term sites ranked in the top five.

| Ranking | Year | Avg. Temp. |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1931-32 | 49.61°F |

| 2. | 1956-57 | 47.41°F |

| 3. | 1948-49 | 46.94°F |

| 4. | 1949-50 | 46.62°F |

| 5. | 1971-72 | 46.37°F |

| 6. | 2016-17 | 45.87°F |

| 7. | 1998-99 | 45.75°F |

| 8. | 2001-02 | 45.68°F |

| 9. | 1932-33 | 45.61°F |

| 10. | 1908-09 | 45.49°F |

Our winter warmth is especially apparent when looking at the nighttime low temperatures. Most Piedmont locations average 45 to 50 days each winter with temperatures at or below freezing. However, in the 90 days from December 1 through February 28 this winter, Greensboro only had 31 days reaching the freezing mark — the 3rd-fewest on record — and Raleigh had 29 such days, or the 6th-fewest on record.

We did feel the chill in early January as temperatures dipped down into the low teens and single digits — the coldest readings across the state in at least two years — but after that, the milder pattern took hold. February alone featured more than a dozen days with high temperatures at or above 70°F across much of the state.

Seasonal Snowfall

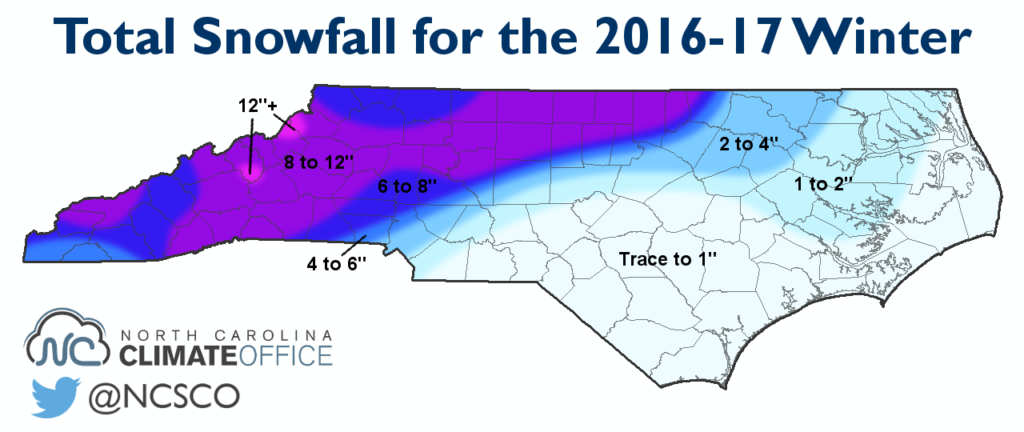

The list of winter storms from the past few months is a short one: There was only one widespread wintry event, which took place on January 6-7. In that event, the Mountains and northwest Piedmont saw 8 to 12 inches of snow, with totals decreasing to the south and east. The Triangle and Charlotte areas saw a transition to sleet and freezing rain, with mainly rain reported in the Sandhills and Coastal Plain.

Snow was even limited high atop Mount Mitchell. The 55.5 inches of total snowfall observed there ranks as the 7th-least in the past 38 years. That value is almost 37 inches below normal, and it’s also more than 45 inches less than the 101.6 and 101.4 inches reported there the past two winters.

Predictions Revisited

Let’s start with the folklore-based forecasts, which generally fared well this winter. While the Farmers’ Almanac was well off on its prediction for “Penetrating Cold and Very Wet” conditions, its similarly named cousin, the Old Farmer’s Almanac, was correct in its forecast for warm, dry weather.

“Hans Solo”, the winning woolly worm from Banner Elk’s Woolly Worm Festival last October, was spot-on with its forecast of a mild winter with the best chance for snow in the first few weeks of January. In the realm of critter-based predictions, our local groundhog, Sir Walter Wally, also had an accurate forecast for an early spring.

Our office’s winter forecast was based less on species and more on science, particularly the global atmospheric patterns last fall and how similar past winters have panned out in North Carolina. Entering the winter, there were two competing patterns: La Niña, which tends to make our winters warm and dry, and a weakened polar vortex, which can increase our chances of seeing cold weather and snow.

With that weak polar vortex in place, we expected the best chances for cooler temperatures to come in December and early January, which was indeed the case. All of the analog winters we studied entered a persistent warm and dry pattern by mid-winter, which was also the case this year.

As we also predicted in our outlook, drought stuck around in the Mountains throughout the winter and has since expanded across most of the Piedmont, per the US Drought Monitor’s latest update.

Current Conditions

One of the main uncertainties within our forecast was the status of La Niña as the winter progressed. If it weakened, we thought that could relax some of its impacts and help us escape from the ongoing dry pattern.

After our 4th-driest February on record, it’s clear that didn’t happen. However, that doesn’t mean that the Pacific patterns haven’t changed. Beginning in mid-February, the final few bubbles of cold water in the central Pacific began to disappear as conditions went from weak La Niña to cool neutral into warm neutral territory over the course of about two weeks!

That doesn’t necessarily mean we’re headed into an El Niño event, but current forecast models give it about a two-in-three chance of developing by the fall, and several factors are working in favor of a developing El Niño.

Notably, the Asian and Australian monsoon patterns were particularly active this winter, bringing above-normal rainfall to that region. As we discussed a few years ago, these monsoon conditions are often the predecessors to low-level convergence and the eastward spread of warm water in the Pacific that can cause an El Niño to form.

Historically, most El Niños haven’t emerged until the late spring or early summer, which gives plenty of time for things to develop. Of course, that also gives plenty of time for things to change in another unexpected way like we saw at the end of last month, which is why there is still plenty of uncertainty with this forecast.

Spring Outlook

Closer to home, these developments in the Pacific aren’t likely to affect us much this spring and summer. For one, this transitioning ENSO state in the ocean means we probably won’t begin seeing broad atmospheric impacts for a while.

In addition, ENSO’s main mechanism for affecting us — the jet streams — will soon begin their typical summertime weakening, which is why we don’t see many warm-season ENSO impacts on North Carolina in the first place.

Climate model forecasts give us a better indication about what our spring may be like, and they’re suggesting more above-normal temperatures like we saw for the last half of the winter. Their precipitation forecasts are less certain, though. Some models show wetter weather for North Carolina while others show an ongoing dry pattern.

The bottom line is that parts of the state remain in drought and it would take more than 4 inches of rain for some of these locations to even reach their normal precipitation for the year to date. So until we see a pattern change, it’s smart to prepare for the threat of a growing drought.

And don’t forget that just because the calendar says it’s spring, that doesn’t mean we can’t still see another chill. The average last freeze date for much of the state isn’t until late March or early April, so climatologically speaking, we’re not out of winter’s woods just yet.