A few drenched days from the tropics’ parting shot to the Southeast amounted to a wet month in North Carolina that also featured sustained warmth. That vaulted us closer to potential new annual temperature and precipitation records.

Eta’s Moisture Drives Wet Weather

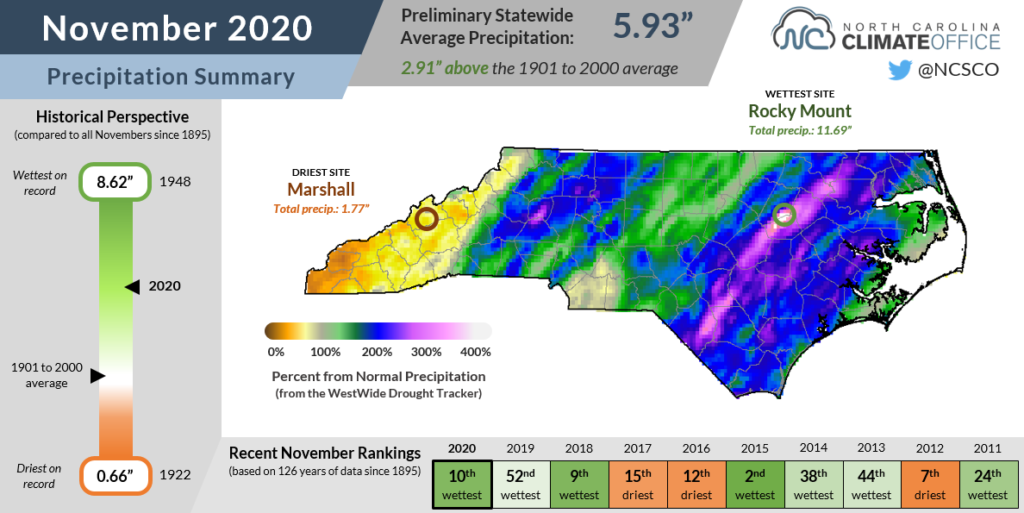

Capping off the hurricane season, tropical moisture from one storm almost single-handedly made it one of the wettest Novembers on record in North Carolina. According to the National Centers for Environmental Information, the preliminary statewide average precipitation of 5.93 inches ranks as our 10th-wettest November since 1895.

Among our rain events during the month, none was as heavy or as impactful as the system on November 10-12 that saw moisture from Tropical Storm Eta pulled northward ahead of a cold front. During that three-day event, totals exceeded 8 inches across the western Piedmont and northern Coastal Plain.

More rain fell on Thanksgiving from another cold front crossing the state. Totals were much lower in this event, with a maximum of about an inch-and-a-half in the southern Mountains.

The month then ended with a final frontal passage on November 30 that brought more than two inches of rain along the coast and an inch or more elsewhere.

Our Taylorsville ECONet station measured 11.31 inches of precipitation during the month, and Rocky Mount also topped the 10-inch mark with 11.69 inches total. Among that amount, 9.86 inches — or 84% of the monthly rainfall — fell during the Eta event.

The only part of the state that missed out on the heaviest rain last month was the far western Mountains. Murphy finished the month 2.2 inches below its normal precipitation, while Marshall received only 1.77 inches, about an inch below normal.

However, those sites still ended the climatological fall more than an inch above their normal seasonal precipitation, and parts of the western Piedmont including Hickory and Marion were more than 10 inches above normal from September through November.

Temperatures Set to Simmer

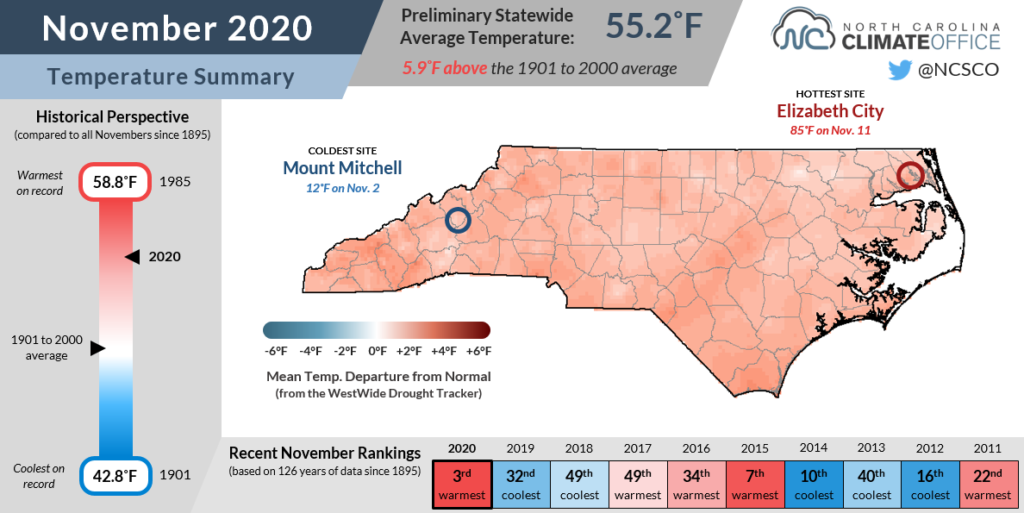

While heavy rain may have been the most noticeable part of our November weather, it was also an especially warm month across the state. NCEI’s preliminary data shows the statewide average temperature of 55.2°F ranks as our 3rd-warmest November out of the past 126 years.

The warmth blanketed the entire state, from a tie for the 4th-warmest November since 1907 in Banner Elk to the 5th-warmest in both Charlotte and Raleigh to the 2nd-warmest in Elizabeth City, which recorded the highest temperature in the state last month with an 85°F high on November 11.

One main source of those September-like temperatures was high pressure over the Southeast coastline that ensured a continuing feed of warm air from the south and southwest, even after the firehose from Eta had shut off.

Wilmington recorded 20 days with high temperatures at or above 70°F — the most there since 2001, and tied for the fourth-most in any November dating back to 1874. Laurinburg hit 70°F or higher on 21 days, which was tied for the second-most November days that warm in the past 74 years.

During the Eta-assisted rain event in the middle of the month, elevated dew points and a saturated air mass even kept the nighttime lows across the southern Piedmont and Coastal Plain in the upper 60s or low 70s — not far from the average daytime highs for that time of the year!

While cool nights were generally hard to come by, sub-freezing temperatures on the morning of November 19 finally ended the growing season across most of eastern North Carolina except for the extreme southern coastline and the Outer Banks.

A Race for the Records?

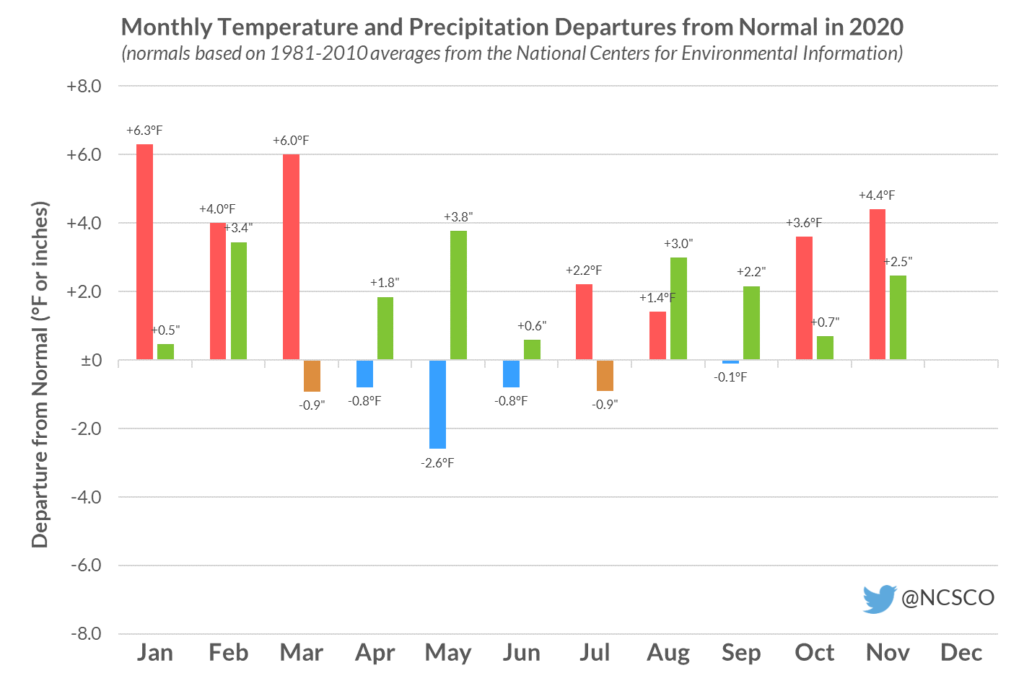

In 2018, we wrung out North Carolina’s wettest year on record. Last year, we sweated through the state’s warmest year on record. Now, amid the craziness of 2020, we have a shot at breaking both records in the same year!

Through the end of November, our year-to-date statewide average precipitation total of 61.69 inches ranks as the wettest on record, a scant 0.40 inches ahead of the pace set by 2018.

The statewide average temperature through the first 11 months of the year is 62.65°F, which is the 3rd-warmest dating back to 1895, and narrowly behind 2017 (62.69°F) and 2019 (62.66°F).

So how extreme does December need to be to break both records? The answer is fairly warm and very wet. The year in 2018 ended with our 3rd-wettest December on record totaling 7.06 inches, so we need a statewide average of at least 6.67 inches this month to break the record. Only six Decembers historically — 2018, 2015, 2009, 1983, 1973, and 1905 — have been that wet.

With the sort of La Niña event currently in place that has historically produced drier winter weather in North Carolina, accumulating enough precipitation in the final weeks of the year to stay atop the precipitation rankings could be a tough task.

Our monthly temperatures need to be slightly warmer than last December, which was the state’s 17th-warmest at 5.0°F above the long-term average, in order to break that record. While La Niña winters are often warmer than normal in North Carolina, the current forecast shows temperatures at or below normal over the next week, including highs in the 40s, so we may need to channel some decidedly un-December-like warmth by the holidays in order to contend for the warmest temperature title.

While two new records this year may be tough to achieve, the notion that this year is even in the same ballpark as the current record-holders is a testament to how consistently warm and wet it has been so far in 2020.

Recall that 2018 included up to three feet of rain in parts of southeastern North Carolina from Hurricane Florence, and in 2019, hundred-degree heat lasted all the way into October en route to a record-setting annual average temperature.

That’s some elite company when you consider the substantial impacts in those years from flooding and heat stress, and in 2020, it has been tough to distance ourselves from them among our state’s climate history.