Warm temperatures dominated January, as did wet weather in western North Carolina, which brought our ongoing drought to an end.

Mild Weather for a Winter Month

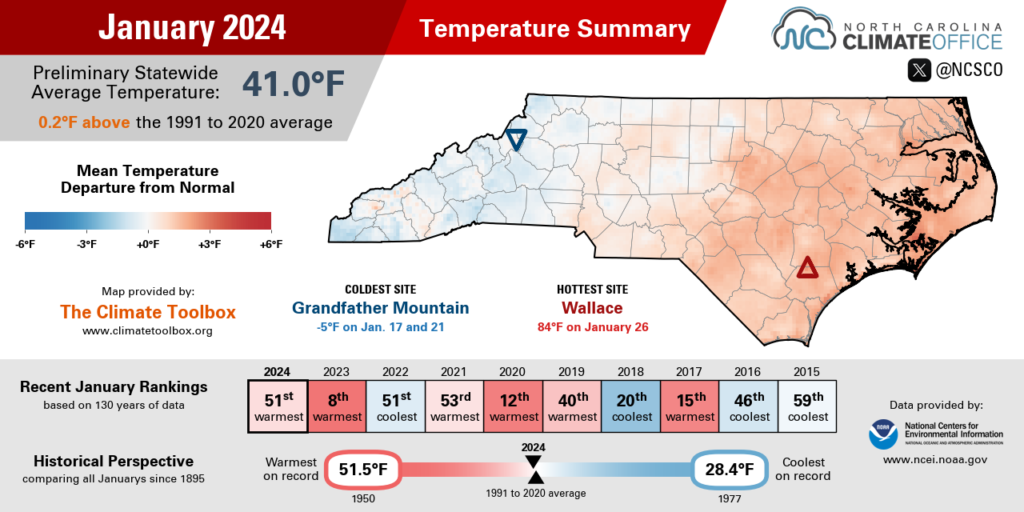

Mostly warm weather, interrupted by a mid-month chill, left our overall temperatures above normal in January. The National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) notes a preliminary statewide average temperature of 41.0°F and our 51st-warmest January out of the past 130 years.

The warmest areas relative to average were in the eastern half of the state, including Fayetteville, which was 4 degrees above normal and tied for its 31st-warmest January since 1910, and Greenville, which was 3 degrees above normal and tied for its 22nd-warmest January on record.

Western North Carolina finished the month at or slightly below their normal January temperatures, with Asheville and Highlands both 1 degree below normal for the month.

Our first big warm-up in the month came on January 9, as temperatures climbed well into the 60s behind a warm front. Lumberton topped out at 70°F, which was the first of eight days that warm last month – tied for the second most in any January there since 1999.

Our temperatures finally tumbled on January 16, as a cold front ushered in a Canadian air mass that had already infiltrated the central United States.

While most of North Carolina avoided the sub-zero temperatures that affected much of the country, a few higher-elevation sites did drop below zero on the morning of January 17, including a low of -5°F on Grandfather Mountain: the coldest reading there since it dropped to -18°F on December 24, 2022.

Elsewhere, temperatures that morning fell into the 10s across the Piedmont and into the 20s in the Coastal Plain. A few days later, on January 21, some eastern areas were even colder, including a low of 25°F at Hatteras – only its second night that cold in the past six winters.

That week of cooler weather eventually gave way to more warmth to end the month, including a stretch of highs topping 70 degrees across most of the state. Even Asheville reached 71°F on January 26 in its first January day that warm since January 1, 2022.

A few eastern sites climbed into the 80s that afternoon, topping out at 84°F in Wallace, which was the warmest winter day on record there dating back to 2000.

Those unseasonable temperatures were enough to send the daffodils into an early bloom from the Triangle eastward – perhaps the most vibrant sign of how warm this January turned out.

Plenty of Precipitation in the West

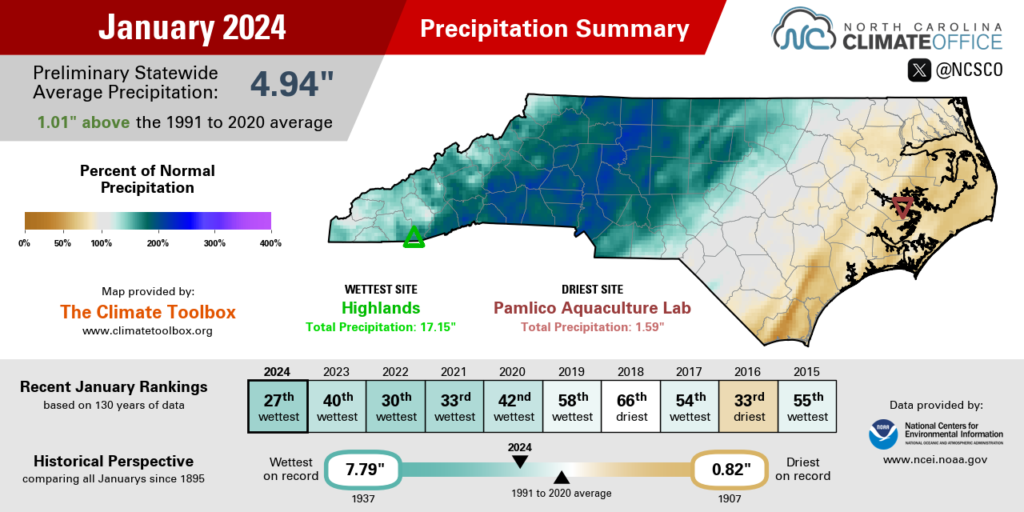

Our wet pattern carried over from December, especially in the Mountains, and made for an overall wetter-than-normal January in North Carolina. NCEI reports a preliminary statewide average precipitation of 4.94 inches, which ranks as the 27th-wettest January since 1895.

At a number of western sites, it finished as the 2nd-wettest January on record, trailing only 1998 – another El Niño-fueled soaking month. Those areas included Asheville (8.79 inches), Pisgah Forest (12.41 inches), Lake Toxaway (16.84 inches), and Highlands (17.15 inches, or more than double its average of 7.99 inches).

Among the many precipitation events last month, some areas received up to 4 inches on January 9, nearly 3 inches on January 25, and more than 5 inches during a weekend-long deluge ending on January 27.

Farther east, it started as a wet month, highlighted by the January 9 cold frontal passage that spawned four tornadoes in Catawba, Craven, and Carteret counties, but the rain later in the month came less frequently and with lower intensity.

It was still an overall wet month across the Piedmont, ranking as the 5th-wettest January in Greensboro, the 8th-wettest in Charlotte, and the 32nd-wettest in Raleigh. In the Triad, the last January wetter than this one was back in 1978.

But it wasn’t a wet month everywhere, as some coastal sites finished the month drier than normal. With only 1.69 inches, Wilmington was 2.12 inches below normal and tied for its 21st-driest January since 1870. Hatteras also had less than half of its normal rainfall in its 22nd-driest January on record.

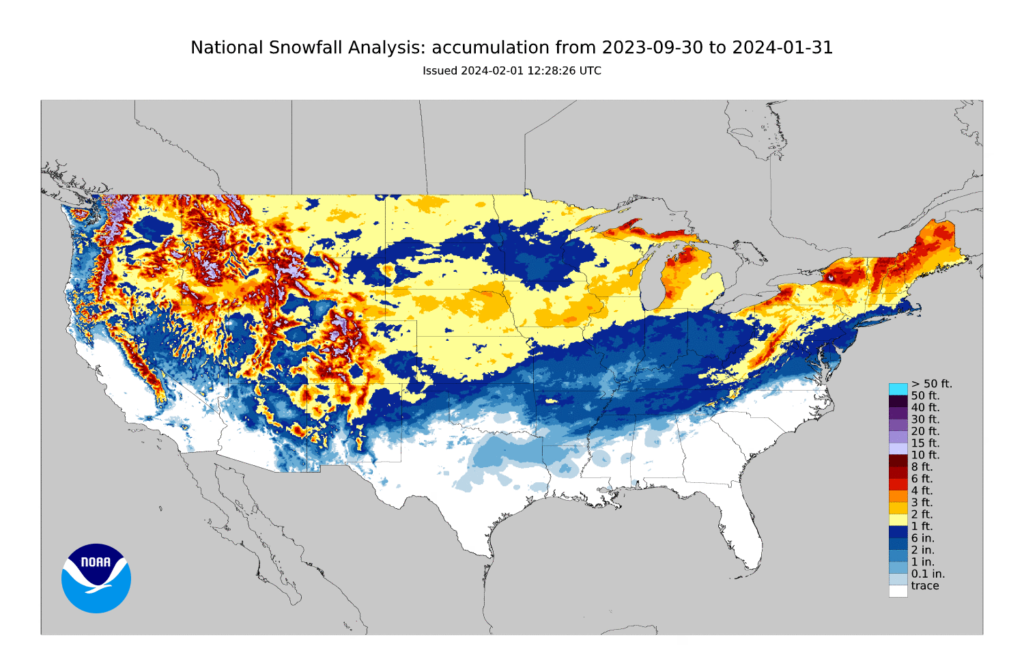

Despite the frequent precipitation chances, snow was elusive for most of the state last month. We weren’t totally shut out, though, as parts of the northern Mountains had several accumulating events. Beech Mountain had a total of 37.2 inches, which was its snowiest month since January 2022, and Boone had 6.7 inches in total, including 2 inches on January 16.

Outside of the Mountains, it has been another snow-free winter so far for most of the state. (The analysis shown below depicts a dusting of snow in parts of the northern Piedmont, including Rockingham County, from December 10.)

The last measurable snow in most areas was in January 2022, which means our current “snow drought” has now passed two years. That’s the second-longest snowless stretch on record for Greensboro, trailing only the 1,169 days without snow ending in February 1993, and also for Asheville, close behind the 736-day streak between February 2011 and February 2013.

If that history is any omen, then both of those record-setting snowless runs ended in February. Perhaps this month will be a streak-buster as well.

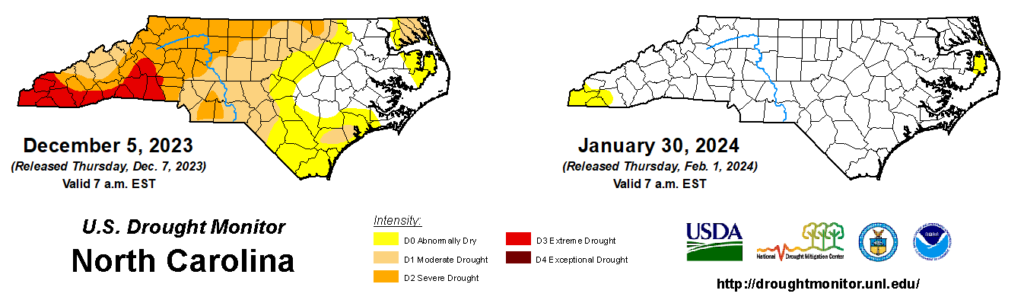

Drought is Out of North Carolina

Seemingly as quickly as it arrived last fall, drought has disappeared this winter thanks to the ample precipitation since early December. The final pocket of Moderate Drought (D1) in far southwestern North Carolina was erased on this week’s US Drought Monitor following 3 to 4 inches of rain there last weekend.

Prior to this week, drought had been present in some part of North Carolina for 24 consecutive weeks, beginning on August 15, 2023. The initially drought-affected areas in the central Coastal Plain received relieving rainfall from tropical storms Idalia and Ophelia, but by that point, dryness had also begun spreading westward, with drought first emerging in the southern Mountains on October 3.

The next month and a half saw the rapid expansion and intensification of drought across the Mountains, and later the Piedmont and southern Coastal Plain, during a bone-dry stretch of October and November.

Between October 14 and November 11, places like Charlotte went almost four weeks without receiving a drop of rain, and the fall ended as the 2nd-driest on record for southern sites including Shelby, Tryon, and Highlands.

That prolonged dry weather, combined with above-normal temperatures, caused surface water levels in lakes and streams to drop, and it prompted the introduction of water restrictions in municipalities and water systems across western North Carolina.

The leaf drop in early November also kicked off an active fall fire season, with notable events including the 5,505-acre Collett Ridge fire in Cherokee County and the 805-acre Sauratown Mountain fire in Stokes County.

Rain just before Thanksgiving was a welcome sight that helped with fire containment, although it did little to quench the thirsty soils or eat into the seasonal precipitation deficits that exceeded 8 inches in some areas.

But that dry fall has been outdone by an even wetter winter. In fact, it’s on pace to be the wettest on record for Greensboro, Hickory, and Lincolnton, among other western Piedmont and southern Mountain locales.

This drought’s total duration of 24 weeks may pale in comparison to historic droughts like the multi-year event from 2007 to 2009, and even compared to recent ones such as the 43 consecutive weeks in drought between October 2021 and August 2022.

But its shorter length belies its abrupt development and overall severity, with the southern Mountains reaching Extreme Drought (D3) in late November and early December. By that measure, it was our worst drought since 2016, and it brought similar impacts as that event.

The rushing streams and puddles on the ground across western North Carolina have made those fall impacts a distant memory, but they’re also a testament to just how quickly conditions turned around this winter to lay this drought to rest.