Stretches of cooler weather left our temperatures below normal last month, but it was still a dry month overall. We also preview the Atlantic hurricane season now in progress.

Temperatures Kept in Check

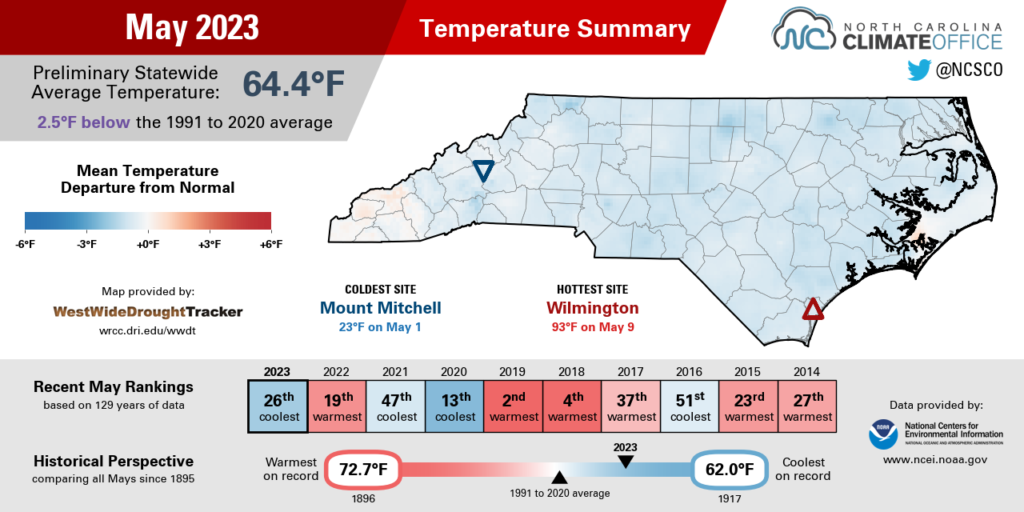

A number of cloudy days and cool air masses from the north kept our temperatures at or below normal seasonal levels last month. The National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) reports a preliminary statewide average temperature of 64.4°F, or our 26th-coolest May out of the past 129 years.

The month started with a deep upper-level low pressure system pushing far south, which kept our high temperatures on May 3 generally in the 60s, with some high-elevation sites stuck in the 40s all day.

After a weeklong warm-up that pushed us back into the upper 80s, another shot of cool air arrived by May 15, with reinforcements just three days later.

Our last – and perhaps most significant – cooldown of the month came on May 27 as high pressure built in from the northwest and low pressure began tracking along the coastline.

With stiff northeasterly winds blowing onshore, the eastern half of the state was socked in with clouds and rain, and high temperatures on that Saturday never made it out of the 60s in most areas. Our ECONet station at the Sandhills Research Station in Jackson Springs topped out at just 59°F, which was only the 11th May day there since 1997 in which temperatures failed to reach at least 60°F.

The moisture hadn’t reached the Mountains at that point in the Memorial Day weekend, which left an unusual occurrence where the warmest sites in the state were in the west, including Murphy and Hot Springs, which both recorded high temperatures of 77°F.

On days like that, temperatures in many areas were held down by persistent cloud cover. Raleigh had 533 hours – or 72% of the month – with mostly cloudy or overcast skies. That was the second-most of any May there since 1973, behind only the 566 hours in May 2009.

Most areas finished the month with mean temperatures 1 to 3 degrees below normal. Greensboro had its 25th-coolest May in the past 120 years, while New Bern tied for its 9th-coolest May since 1949, and Plymouth tied for its 8th-coolest since 1945.

Another measure of our cool May is just how few areas hit the 90-degree mark. While the average first 90-degree day occurs in mid to late May – timing that we generally matched last year – only a few parts of the Sandhills and southern Coastal Plain have been that warm so far in 2023.

That includes Wilmington, which hit 90°F on May 8 and 93°F on May 9, and Lumberton, which has topped 90°F just once this year, on May 9, compared to 14 days that warm through the end of May last year.

Late Rain Can’t Bail Out a Dry Month

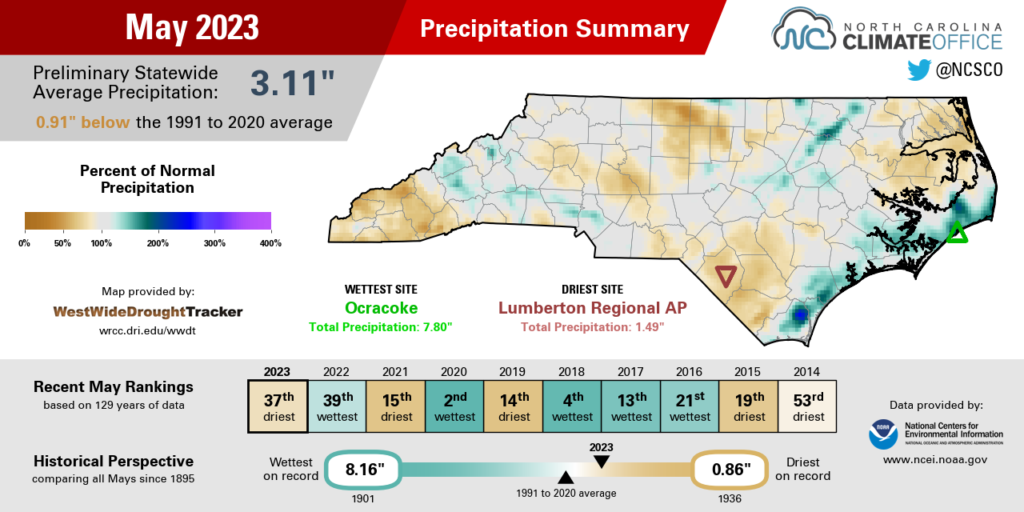

Despite Mother Nature’s best efforts on a soggy final weekend, we couldn’t overcome the dry start to the month. NCEI reports a statewide average precipitation of 3.11 inches and our 37th-driest May since 1895.

Early in the month, rain was tough to come by, and some southeastern sites such as Wilmington went 13 days in a row without any measurable rainfall. That area was eventually inundated by more than 4 inches of rain on May 19, which caused flooded roads in Brunswick and New Hanover counties.

Elsewhere, there were notable rain events in the northern Piedmont on May 13-14 associated with showers along a cold front, and in the Mountains on May 15-16.

The wettest and most widespread rain event came during Memorial Day weekend. More than 3 inches fell in the central Mountains, and more than 2 inches was recorded in the Triad and our northwestern counties, and also right along the coastline.

While much of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain finally broke their streaks of wet weekends early in the month, some western sites were not so lucky. Through the end of May, Asheville has seen measurable rainfall ten weekends in a row, and on 16 of 21 weekends so far this year.

A few areas did finish the month wetter than normal, including New Bern, with its 28th-wettest May in the past 71 years, and Wilmington, which had its 26th-wettest May and was just over an inch above normal.

The dry spots across each region included Elizabeth City, which was more than 2 inches below normal in its 12th-driest May on record; Raleigh, which had only about half of its normal monthly rainfall in its 19th-driest May; and Highlands, which was 2.6 inches below normal in its 34th-driest May out of the past 121 years.

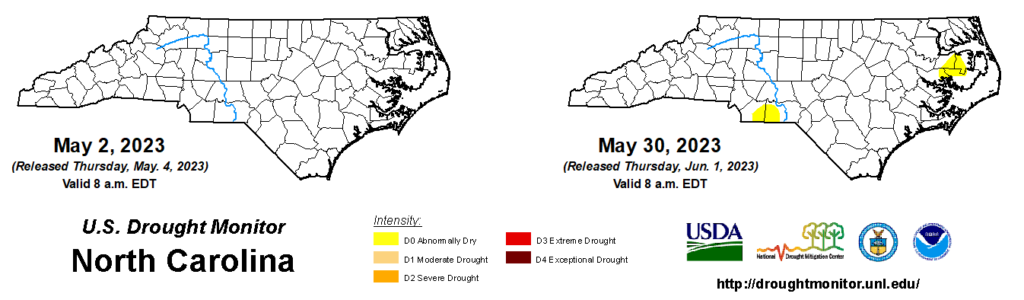

While residual moisture from our wet April slowed the emergence of any impacts, a few areas of Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions have bubbled up on the state drought map. Currently, parts of the southern Piedmont and central Coastal Plain are classified as Abnormally Dry. These areas missed out on the heaviest rainfall in April and finished the climatological spring drier than normal.

The far western Mountains have also been drying out, and areas west of Waynesville picked up less than half an inch of rain over Memorial Day weekend. With streamflows falling below normal in that corner of the state, it could be the next area officially classified as dry without rain soon.

Hurricane Season Hangs in the Balance

A year ago at this time, we entered the 2022 Atlantic hurricane season with high confidence of seeing lots of activity across the basin. After all, the La Niña pattern in place was favorable for storms to form, and under similar conditions the previous year, there were 21 named storms in 2021.

But thanks to a nearly two-month gap with no storms between early July and early September, it ended up being an average season overall. Nicole in mid-November was the fourteenth and final named storm, matching the 30-year average for the Atlantic.

Entering this hurricane season, the background atmospheric patterns have shifted from a year ago, which gives this season’s outlook a different flavor following three consecutive La Niña years.

There are a few key factors expected to influence this year’s tropical activity, and like weights on a scale, some of them tend to balance out others.

In the Pacific, the long-lived La Niña has been quickly replaced by an emerging El Niño. If it continues to develop and mature as expected this summer and fall, then it’s likely to strengthen the upper-level winds across the Atlantic, which could shear apart developing storms.

On the other hand, the ocean surface in the Atlantic is warmer than normal at the moment, which would support increased activity. In addition, the West African Monsoon is predicted to be especially active this summer, which could send more moisture-rich tropical waves across the Atlantic.

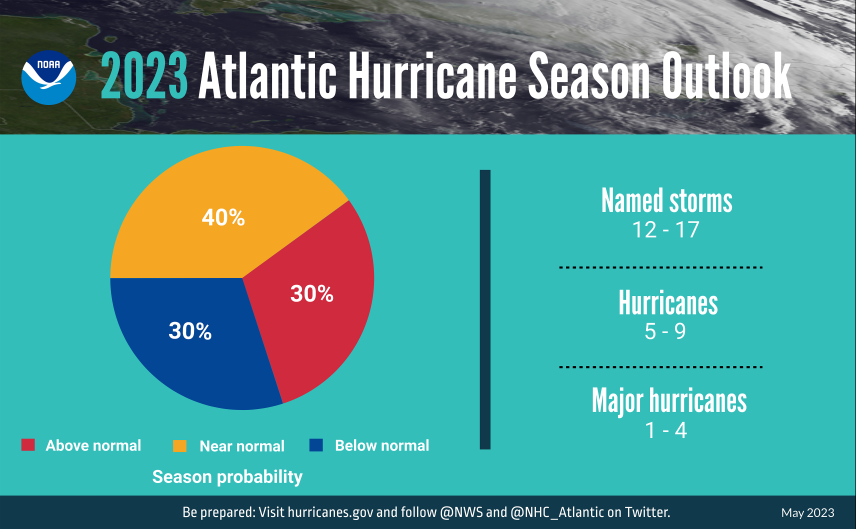

With those competing factors in mind, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is predicting near-normal activity this season, with 12 to 17 named storms, 5 to 9 hurricanes, and 1 to 4 major hurricanes. The 30-year averages are 14 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes.

The first named storm of this season, Arlene, formed over the Gulf of Mexico on June 2. The National Hurricane Center also confirmed that a low pressure system off the Northeast coast in mid-January met the criteria of a subtropical storm, although it went undesignated — and thus, unnamed — at the time.

While NOAA predicts a 40% chance of near-normal activity, there is also a 30% chance of it being above normal and a 30% chance of it being below normal, showing just how sensitive the outcome is likely to be to those large-scale patterns at play.

A thumb on the scale in the form of a less-potent El Niño could encourage more activity, while shifts in local conditions such as cool water or Saharan dust blowing across the Atlantic could limit the number of storms.

Statistics for North Carolina show that we see a direct landfalling storm about every 2 years, on average. Our last landfalling storm was Hurricane Isaias in 2020, although we’ve seen impacts from several storms since then. In 2021, the remnants of Tropical Storm Fred drenched the southern Mountains, while last year, the remnants of both hurricanes Ian and Nicole produced heavy rain and gusty winds across the state.

No matter what the outlook shows or how long it has been since a storm affected your area, it’s always smart to prepare for potential impacts. After all, nowhere in North Carolina is immune to damage from tropical storms, whether that’s from storm surge, freshwater flooding, high winds, or even landslides.