A persistent Pacific pattern is back again, putting us in line for a rare triple-dip La Niña this winter. But with each of the past two winters playing out very differently in North Carolina, what can we expect this year?

In our eleventh annual winter outlook, we’ll examine the current ENSO conditions, the rarity of a third consecutive La Niña, how our weather might look this winter, and how recent snow events have shaped up across the state.

ENSO’s Recent Evolution

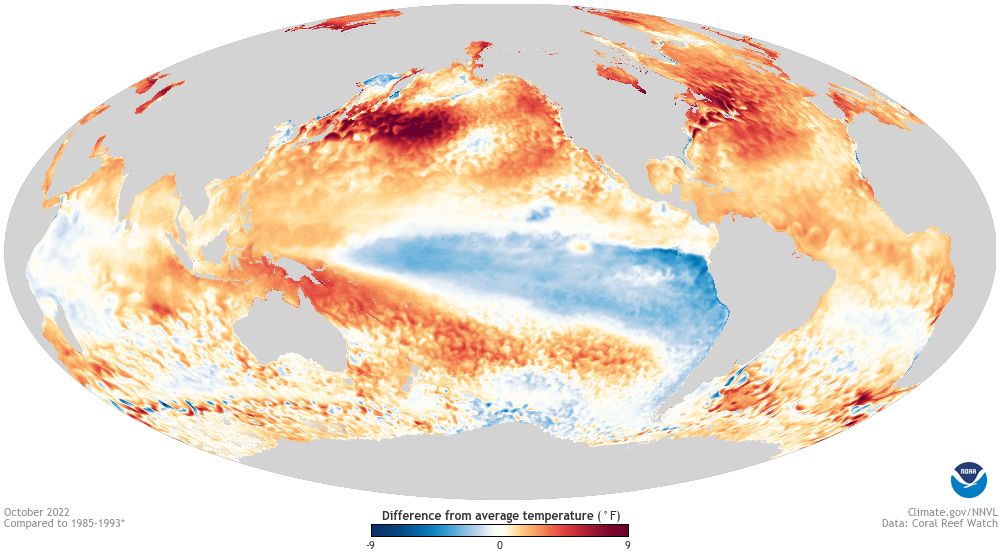

Since it first emerged during the late summer of 2020, the La Niña pattern has been remarkably stable. Sea surface temperatures across the equatorial Pacific have been at least a half-degree Celsius below normal for 24 of the past 26 months, as assessed by the Oceanic Nino Index, which uses three-month running averages.

Even this summer, when ENSO conditions often slacken or transition between phases, there was little doubt about the ongoing La Niña, as sea surface temperatures remained at least 0.8°C below normal.

It’s easy to spot the current La Niña pattern on maps of sea surface temperature anomalies, as a wedge of cooler water extending westward from the coast of South America.

Its atmospheric signature is also present, with above-normal outgoing longwave radiation over the western Pacific – a sign of decreased cloud cover associated with high pressure across that region – and a strengthening of the easterly trade winds along the equator.

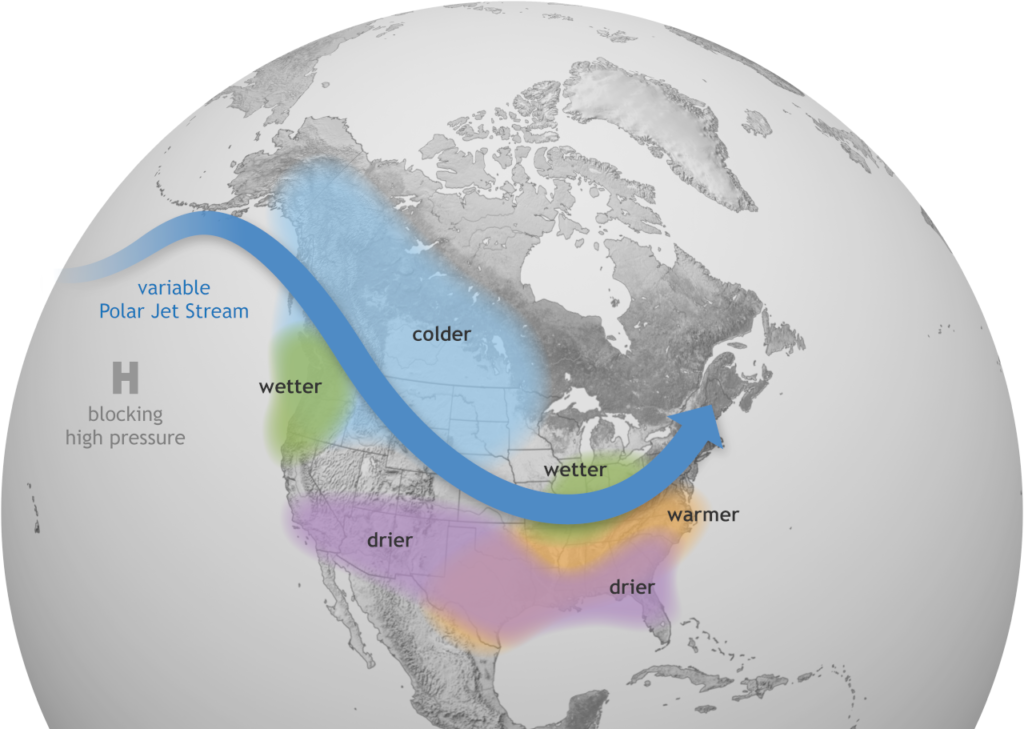

All of that tells us La Niña is mature and well-established heading into the winter, which increases the confidence that it will influence our weather for at least part of the season. Often, that means warmer and drier conditions across much of the Southeast US as the jet streams weaken and retreat to the north. Of course, our recent history tells us that’s not the case every year.

While our current La Niña pattern began with the 2020-21 winter, you’d never know it by our weather in North Carolina. That winter ranked as our 12th-wettest on record, and it was characterized by an active storm track from the Gulf of Mexico over the Carolinas – a pattern more typical of an El Niño event.

Last winter brought more typical La Niña impacts, ranked as our 10th-warmest and 45th-driest since 1895. However, the large-scale pattern shifted in January, with cooler and wetter weather in North Carolina, including several snow events.

Each of those was a moderate La Niña, with a wintertime Oceanic Nino Index of 1.0°C below normal. The Climate Prediction Center’s consolidated forecast is predicting an identical one-degree anomaly this winter.

There are reasons to believe that this winter’s La Niña might not be as strong, though. As NOAA’s latest ENSO Blog post notes, Pacific trade winds have weakened in the past week or so, and seasonal forecast models are showing a decay of this La Niña through the winter, with a return to ENSO-neutral conditions likely by the spring. That would also fit with ENSO’s typical evolution, which often sees the peak strength during the October through December time frame.

NOAA’s Emily Becker rightfully notes that “La Niña, and its effect on rain, snow, and temperature is very likely to continue through the winter, regardless exactly when the minimum Niño-3.4 anomaly occurs.” But if the recent trends continue, it could at least make this La Niña wind up as the weakest of our recent triplet.

Three in a Row?!

While it’s not uncommon for La Niñas to double dip in back-to-back years, it is rare to see them for three consecutive winters. Since 1950, it has only happened two other times: from 1974 to 1976, and 1999 to 2001.

With such a small sample size, it’s tough to tell if the third La Niñas in line tend to share any common characteristics. However, some evidence does suggest that when La Niña hangs around for more than one year, its impacts tend to be more pronounced, especially to our wintertime precipitation.

That was especially true during the last triple dip La Niña. Drought gripped North Carolina beginning late in 1998, when La Niña first emerged, and it persisted through the summer of 2002 in the hardest-hit areas including the western Piedmont.

The cumulative impact of those three La Niñas, along with several locally uneventful hurricane seasons, was astounding. During the four years from 1999 to 2002, Hickory was 61.65 inches – or more than a year’s worth of rainfall – below its normal precipitation.

Fortunately, we haven’t seen such deficits build up during the current long-lived La Niña. Over the past 2 years, Wilmington is about 16 inches below normal, and much of the Piedmont is near or slightly above normal.

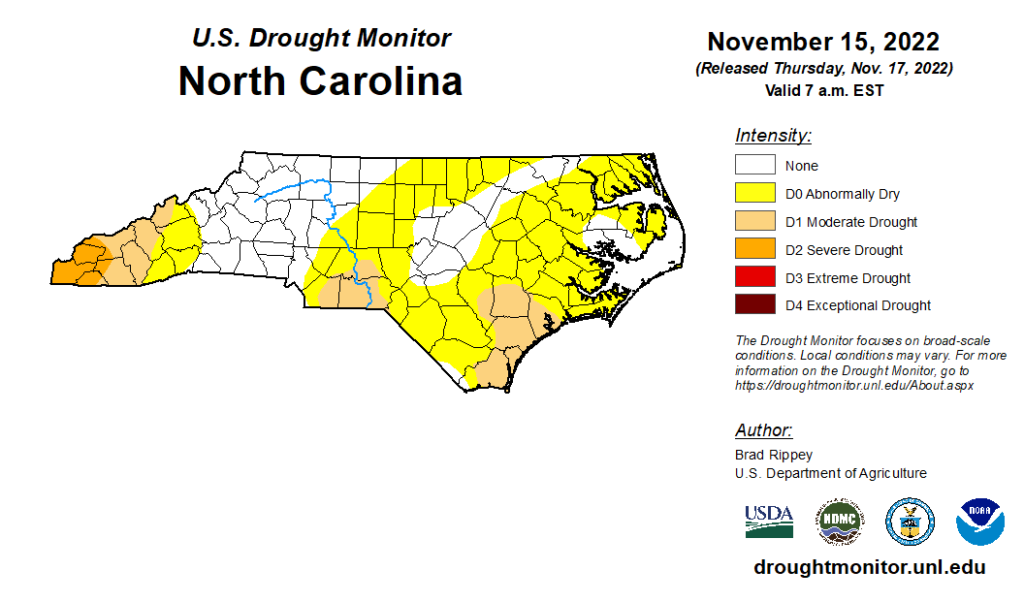

But that doesn’t mean drought is not a concern at the moment. Particularly after our dry October, much of the state has slipped into abnormally dry or drought conditions, and even after Nicole, seasonal rainfall deficits remain in some areas. That means drought and its evolution will continue to be a storyline in the months ahead.

This Winter in North Carolina

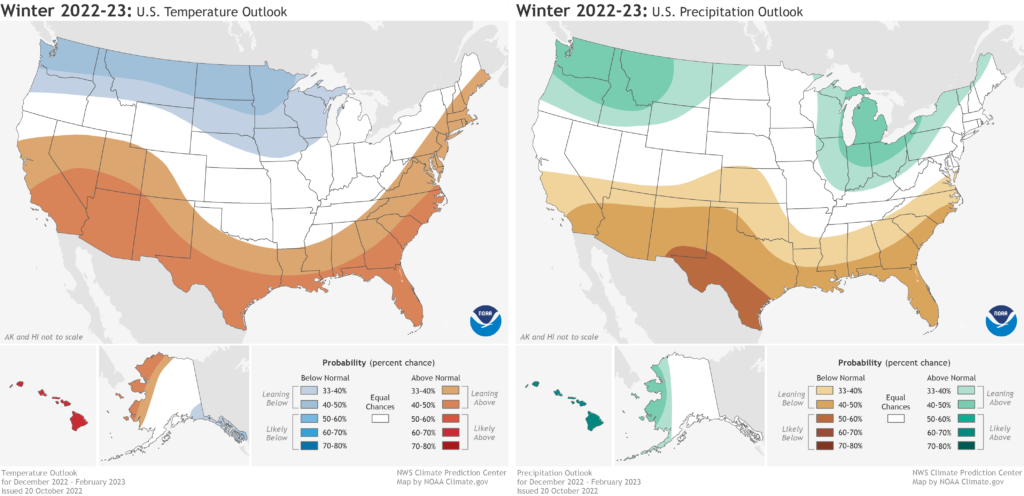

Given our history with La Niña events, it’s reasonable to expect warmer and drier conditions overall this winter. NOAA’s winter outlook accordingly shows increased chances for above-normal temperatures and below-normal precipitation across much of North Carolina.

In the 25 La Niña winters since 1950, 19 have been drier than normal and 18 have been warmer than the 20th-century average in North Carolina, including seven of the past eight. Our recent winters have also been warming due to climate change. The statewide average wintertime temperature since 2001 has been 1.7°F warmer than the 20th-century average.

That doesn’t mean the entire season will be warm and dry, though. ENSO’s grip on the jet streams tends to loosen at some point each winter, and patterns closer to home – including cold air sneaking in from Canada and storms tracking along our coastline – can offer some variety. While La Niña winters do tend to be less favorable for wintry events, we can’t totally rule them out either, as last January showed.

In our past eight La Niña winters, snow has fallen as early as November 21 (in 2008) and as late as March 21 (in 2018), but it’s most common in January. In Raleigh, 10 of the 21 days with measurable snowfall in the past eight La Niña winters have happened in January. That makes it a key month to watch this winter as well, both for snow chances and potential drought recovery.

Despite being drier than normal overall, drought conditions faded last winter, from more than half of the state classified in Severe Drought (D2) in early December to just 9% of the state in Moderate Drought (D1) at the end of February. We owed that improvement to reduced evaporation and cool-season water demand, and a timely moisture recharge from our slow-soaking precipitation events in January.

A less favorable scenario would be an unflinching La Niña pattern like in 2010-11, which saw three consecutive dry months across the state and overall drought degradation, including unseasonably early fire activity during a stretch of windy days in mid-February.

Even if it’s not accompanied by worsening drought or wildfires, those early warm-ups are always something to watch for. In each of the past 11 La Niña winters, February has been warmer than the 20th-century average, including the record-breaking warmth in February 2018 that included 80-degree temperatures by mid-month.

A Snow Drought Update

At this time last year, parts of the southern Piedmont had gone almost four years without seeing even an inch of snow on the ground. We chronicled those “snow droughts” in a blog post last November.

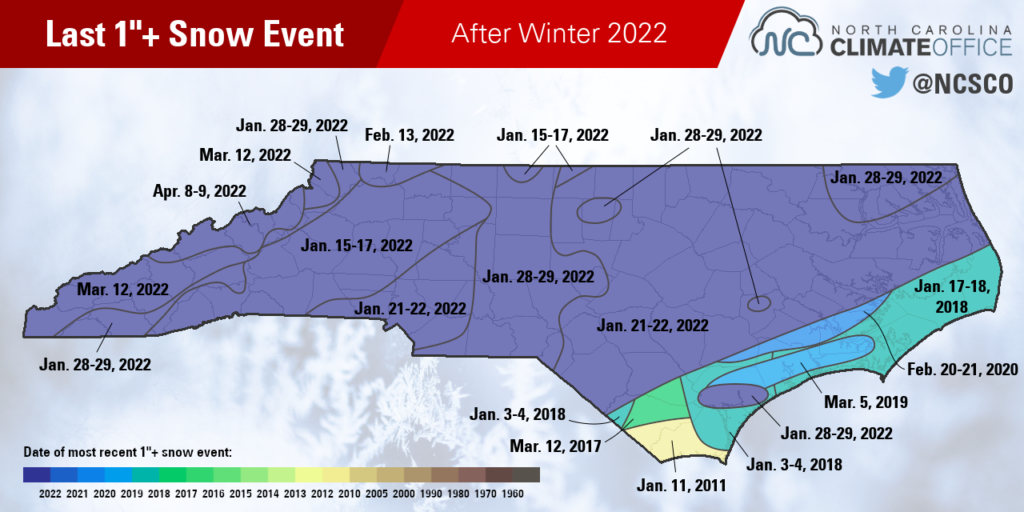

Just two months later, our almost-weekly January snow events had a little something for almost everyone in the state. As the map below indicates, it has now been less than a year since the last one-inch snow event in most areas, except for the far southern and central coast, which had more ice than snow last winter.

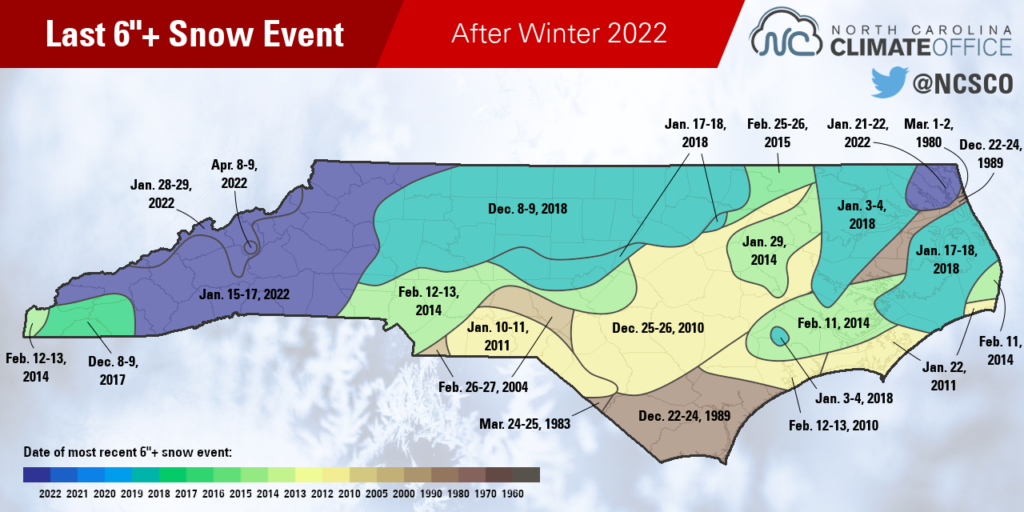

Heavier snow amounts were harder to come by last winter, but much of the Mountains and the far northeastern corner of the state picked up more than six inches during one of our winter storms.

In Elizabeth City, it was only the second six-inch snowstorm in the past 20 years, joining a 7-inch accumulation in late January 2014.

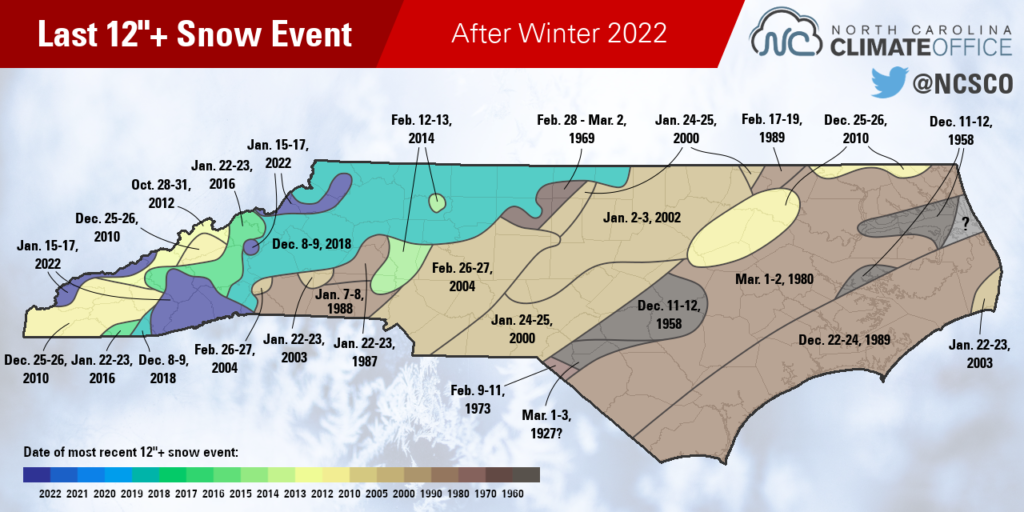

For most of the state, it has still been several decades since the last 12-inch snow event. Much of eastern North Carolina last saw a foot on the ground in the 1980s, and parts of the Triad including downtown Greensboro have to go back even further, to early March 1969.

Some western sites did see such heavy totals during the mid-January storm earlier this year. Brevard had a two-day total of 12 inches on January 16-17, which was the first foot of snow there since December 9-10, 2018.

Snow is never a guarantee in North Carolina, especially in La Niña winters. But as last January showed, windows of opportunity can still open.

Given a pattern change and enough cool air and offshore moisture converging at just the right times, sizable snow events are still possible, even amid an overall warm and dry winter.