It’s not even Thanksgiving yet, but for some meteorologists, it’s feeling a bit like Groundhog Day.

For the second year in a row, a La Niña event is developing as we head into the winter, leaving us to wonder how — or even if — it will affect our weather.

Last year’s event never produced the expected impacts of warmer and drier weather in North Carolina. In fact, it was an overall wet winter that behaved more like an El Niño event locally, potentially because warmer water just north of the equator affected the atmosphere in a similar way as a warm-phase ENSO pattern.

What does the current La Niña look like?

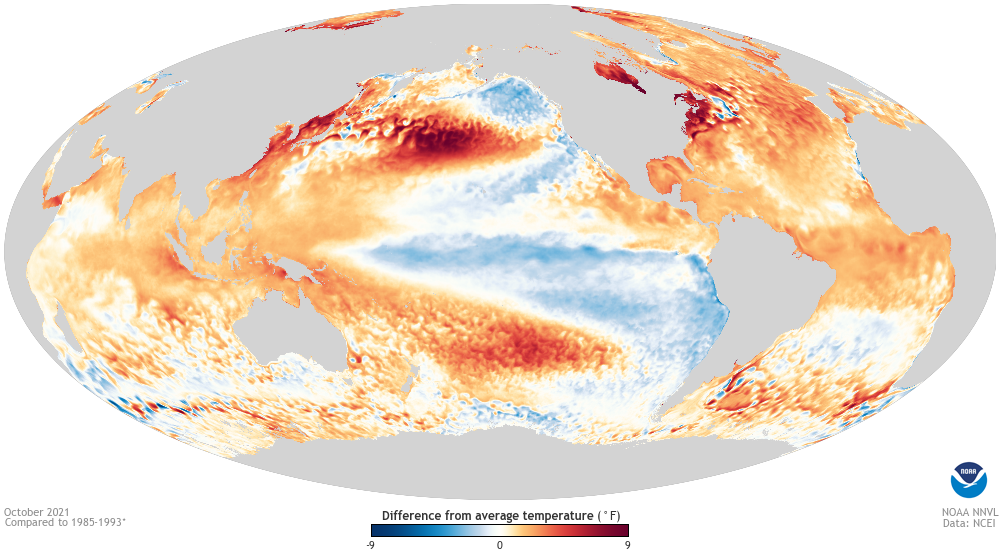

Since early August, sea surface temperatures across the equatorial Pacific Ocean have steadily cooled, and we’re now seeing the telltale tongue of cooler water extending westward from the South American coast associated with a maturing La Niña.

It is already having atmospheric impacts across the central Pacific, including a strengthening of the easterly trade winds and increases in outgoing longwave radiation, caused by clearer skies that allow more of the sun’s energy to reflect back to space.

Most forecasts predict the sea surface temperature anomalies should peak at around 1°C below normal, making this a moderate La Niña on par with the strength of last year’s event.

There’s another similarity to last year as well. At this point, most of the cool water is again south of the equator, with a small region of warm water to the north off the Central American coast. If that asymmetry persists, it could again limit La Niña’s impacts across the Northern Hemisphere.

How rare are back-to-back La Niña events?

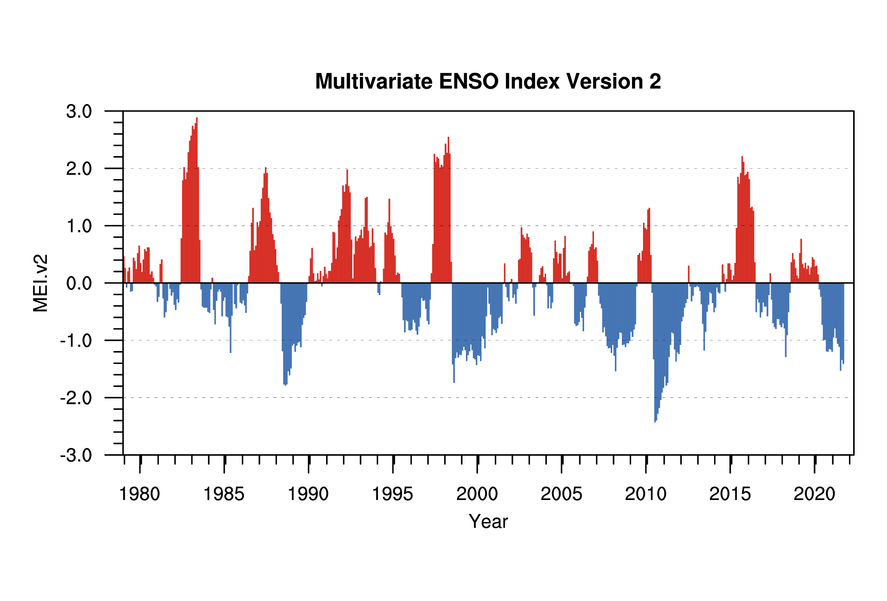

We sometimes describe ENSO as a cyclical pattern that implies a metronomic predictability, swinging back and forth between El Niño and La Niña with a reset every summer, but it’s not always that straightforward.

In some years, neither an El Niño nor a La Niña becomes established, putting us in a neutral phase, with sea surface temperature anomalies between -0.5 and +0.5°C. In those winters, other atmospheric patterns typically play a greater role in our weather.

Other times, the pendulum swings the same way twice in a row. That is happening this year as we enter a second consecutive La Niña.

These “double dip” La Niña events are more common than you might expect. Since 1950, 16 of the 23 La Niña winters have been part of back-to-back (or back-to-back-to-back) events, meaning they happen about 70% of the time.

As NOAA’s ENSO Blog explains, weaker atmospheric impacts during a La Niña event, like we saw last year, actually make a double dip more likely. That’s because ENSO-induced changes in wind patterns are not as effective at moving the characteristic cool water away from the equator, leaving the ingredients in place for another La Niña the next year.

Some evidence suggests that the second La Niña event in a double-dip scenario can have more pronounced climate impacts, particularly to decreasing precipitation across the Tennessee Valley. Of course, after seeing few to no La Niña impacts last year, it won’t be difficult to exceed those this winter.

What does this mean for our drought?

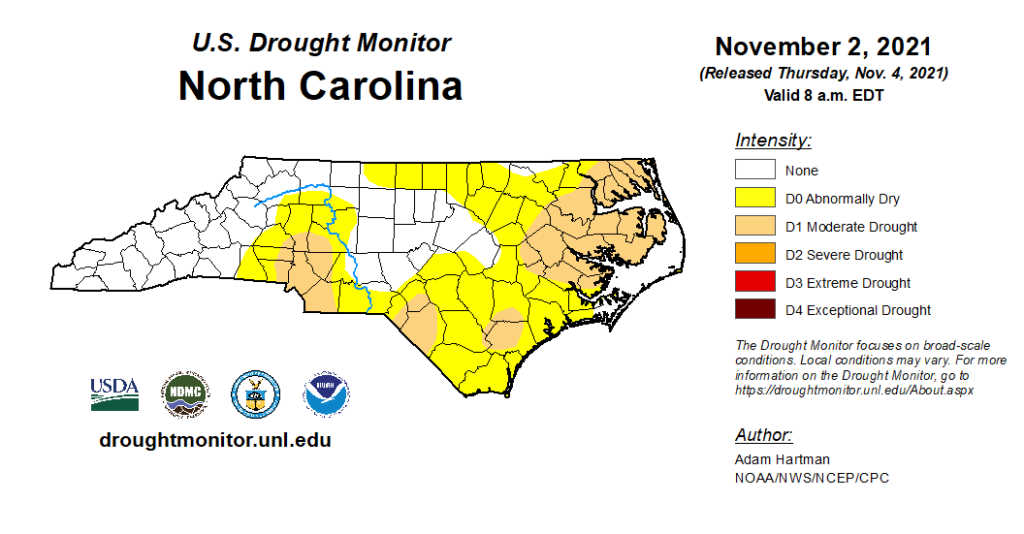

A dry forecast courtesy of La Niña isn’t ideal given that we already have drought in place across parts of North Carolina, but it’s also no guarantee of worsening drought conditions.

In 2017-18, we entered the winter with Moderate Drought covering much of the Piedmont, and even after a drier-than-normal winter — our 40th-driest dating back to 1895 — drought had retreated to the Virginia border by the end of February and disappeared entirely by late March.

Thanks to lower evaporation and irrigation demands, cool-season precipitation goes a long way in maintaining soil moisture, streams, and lake levels, so we could even tolerate a drier winter without significant degradation of drought conditions.

Our main concerns will be the impacts of any longer-term moisture deficits entering the spring. For instance, groundwater wells or reservoirs that don’t see much wintertime recovery could create local water supply shortages and warrant conservation measures, while dry forests could be primed for an early-starting spring fire season, as was the case exiting the La Niña winter in 2010-11.

What is the winter outlook for North Carolina?

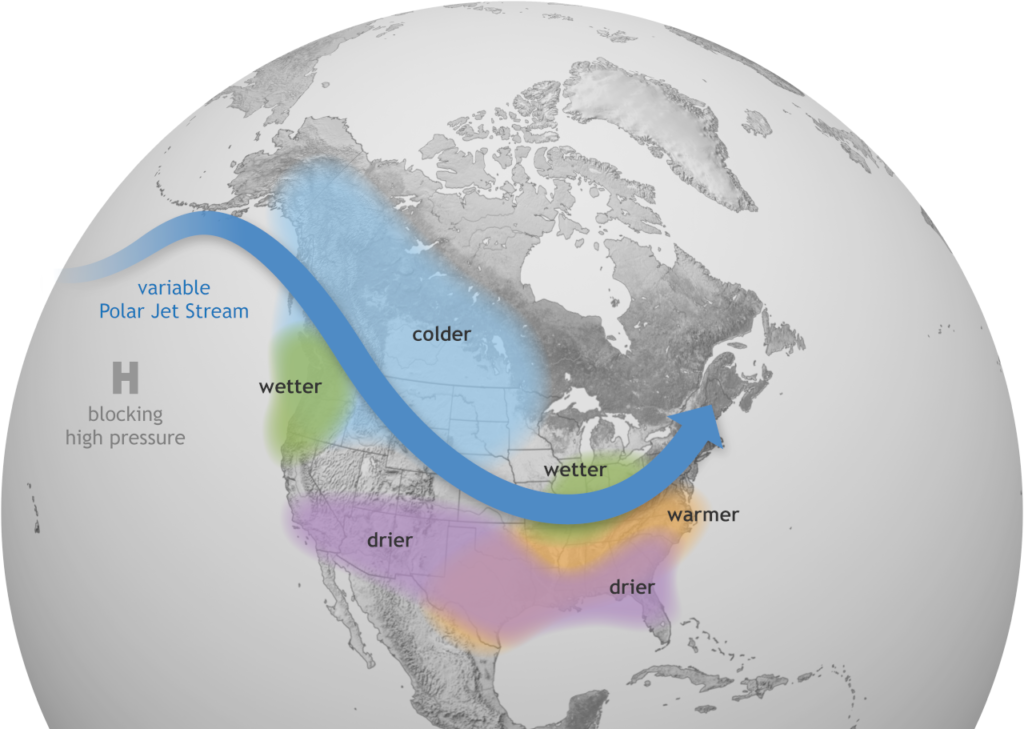

Historically, the nine double-dip (or triple-dip) La Niña winters have been drier than normal across the Southeast US and warmer than the long-term average for much of the southern and eastern part of the country.

NOAA’s winter outlook closely reflects those patterns, giving much of North Carolina at least a 50% chance of seeing above-normal temperatures, with slightly elevated odds of below-normal precipitation.

That follows from La Niña’s typical atmospheric impacts of jet stream ridging over the eastern US, with the predominant storm track bypassing us to the north over the Ohio Valley.

A warm winter would also fit with our recent trends due to climate change in North Carolina, with warming temperatures overall and fewer cold days as noted in the NC Climate Science Report. Each of our last six winters has been warmer than the long-term average, and we’ve recorded four of our top ten warmest winters on record in the past decade.

The precipitation outlook is clouded by a bit more uncertainty, mainly because of how last winter played out and similarities with the current Pacific sea surface temperature anomalies. Climate model forecasts reflect the range of potential precipitation scenarios. A majority favor dry conditions for North Carolina, but some show more extreme dryness while a few outliers show above-normal precipitation for parts of the state.

Will it snow?

Maybe. But that’s all the confidence we can muster going into a winter like this.

In any winter, snow events in North Carolina require a careful combination of cold air and moisture with just the right timing and amounts of each. The large-scale patterns associated with La Niña make such a setup even tougher to come by, so La Niña winters tend to be a bit less snowy, both in accumulations and frequency.

While decent snows have happened in La Niña years, we’ve also gone snow-free through those winters. Even last year in an overall wet pattern, accumulating snow was limited to the northern and western parts of the state during a couple of minor events.

Entering this winter, areas farther south and east remain mired in “snow droughts,” as the last measurable snow in the Sandhills and southern Coastal Plain came in January 2018.

That’s not quite record territory — Wilmington went almost six years without accumulating snow between 2003 and 2009, and Fayetteville had a seven-year snow drought end in January 2009 — but flakes have indeed been fleeting for some parts of the state over the past few years.

Given that recent history and an unfavorable ENSO pattern for wintry precipitation this year, perhaps a better question than “Will it snow?” is “Are you feeling lucky?”