Bookended by heat, August wrapped up a warm summer statewide, while scattered showers brought our ongoing drought to an end. We also turn to the tropics and review a rare storm-free August.

A Warm Summer Wraps Up

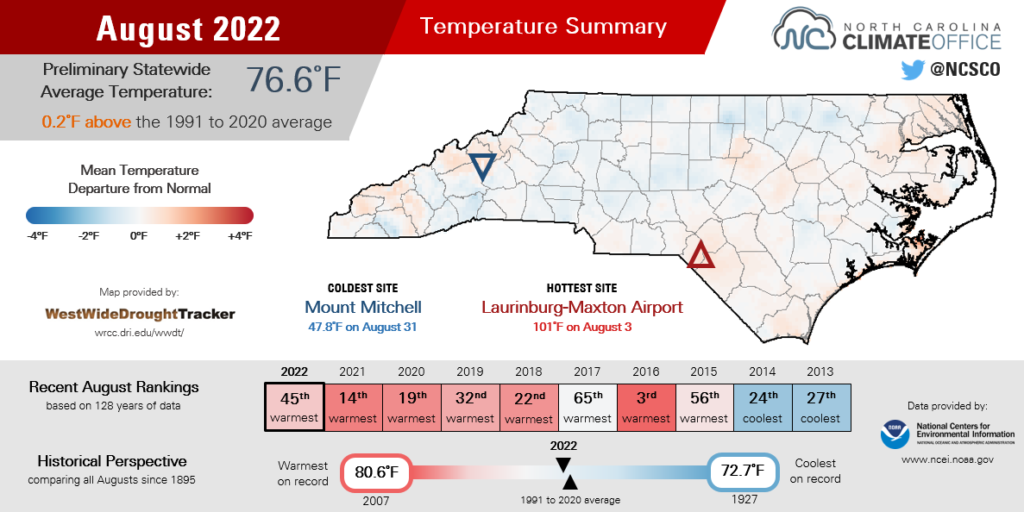

A hot start and end to August were balanced by cooler mid-month weather, but it was still a warmer-than-normal month overall. The National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) reports a preliminary statewide average temperature last month of 76.6°F, which ranks as our 45th-warmest August since 1895.

Under the control of high pressure centered over the Carolinas, early August saw a continuation of the hot and humid dog-day weather from July. High temperatures reached the upper 90s on August 9 and 10.

Our ECONet station at Jockey’s Ridge State Park hit 97.5°F on August 9, which is the warmest temperature recorded there since the station was installed earlier this year, and more than 10 degrees above normal for that part of the northern Outer Banks.

After that, heat relief arrived by August 12, as a pair of cold fronts moving in from the northwest packed a one-two punch of needed rainfall and cooler, less humid air.

On the morning of August 14, temperatures in some areas bottomed out in the 50s, including a low of 59°F in Jacksonville. That was the first night in the 50s there since June 22. In the Mountains, Sparta and Mount Mitchell both had a low of 49°F on August 13 – the first feel of fall after a steamy summer, even at our high-elevation locations.

The month ended with the return of high pressure over the Southeast and temperatures well into the 90s across North Carolina, reminding us that summer wasn’t quite finished yet.

Through the end of August, Raleigh has recorded 69 days this year with temperatures reaching at least 90°F. That’s the second-most all time, trailing only 2010, which had 75 such days at this point in the year.

Back in 2010, we tacked on 16 more 90-degree days in September, so it will be a challenge for the capital city to contend for the outright annual record. In any case, this was an especially warm summer in Raleigh – the 3rd-warmest on record, in fact – with few breaks from the heat.

Elsewhere, Wilmington tied for its 4th-warmest summer and Charlotte had its 10th-warmest summer all-time, which was the warmest there since 2016.

Statewide, on the strength of three consecutive warmer-than-normal months, it was our 15th-warmest summer on record, according to the preliminary data from NCEI. Each of our past eight summers, and 16 of the past 18, have been warmer than the 20th-century average.

Showers Bring Drought Relief

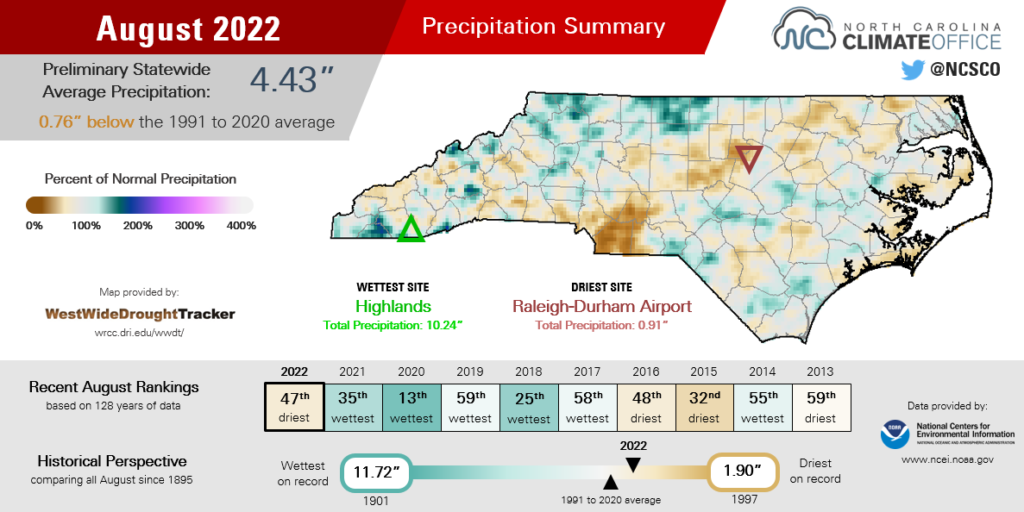

Across the state, a mixture of wet and dry conditions averaged out to a preliminary statewide average precipitation of 4.43 inches and our 47th-driest August in the past 128 years, according to NCEI.

There were few widespread precipitation events during the month. Instead, pop-up showers and thunderstorms were responsible for most of our rainfall, which left some areas soaked while others missed out.

Parts of the Piedmont were notably dry, including only 0.91 inches of rain all month in Raleigh, which ranked as tied for its 2nd-driest August dating back to 1887. Monroe measured just 2.33 inches all month for its 20th-driest August in the past 127 years.

Among the wetter areas, Hickory picked up 3.45 inches of rain from slow-moving storms on the afternoon of August 6 and finished the month 3.3 inches above normal, with its 9th-wettest August in the past 73 years.

In the east, Plymouth had a combined 4.79 inches during the frontal passages on August 11 and 12, which made up more than half of its 8.90-inch monthly total.

That event also brought well-placed showers across the central Coastal Plain. Weekly totals of more than 4 inches in Goldsboro and 2.8 inches at Fort Bragg were enough to lift those areas out of drought for the first time since mid-March.

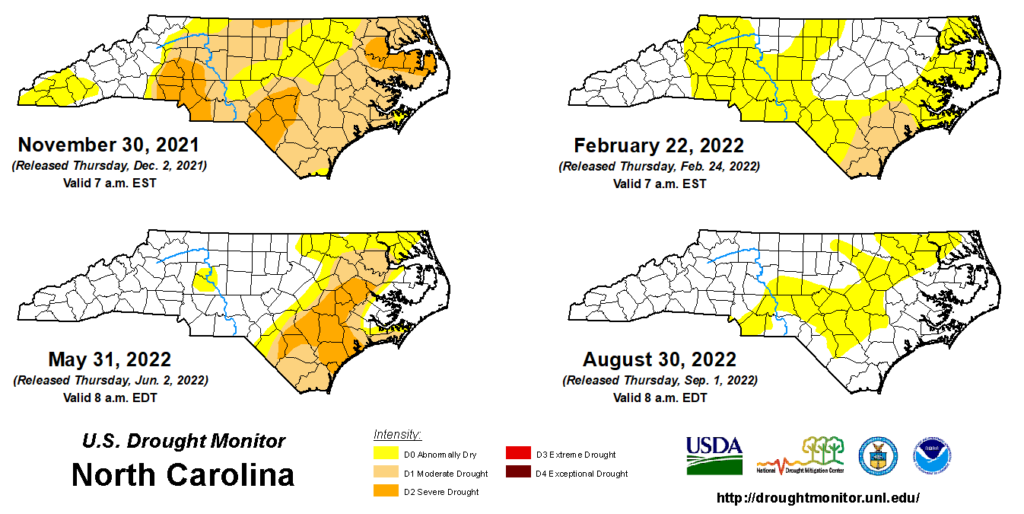

As that final patch of Moderate Drought (D1) finally disappeared on the August 23 map, we ended a run of 43 consecutive weeks with drought present in North Carolina. That ranks as our fifth-longest streak since the US Drought Monitor began officially tracking conditions in 2000.

| Consecutive Weeks with Drought in NC | First Week of Streak | Last Week of Streak |

|---|---|---|

| 155† | Jan. 4, 2000 | Dec. 17, 2002 |

| 117 | Feb. 13, 2007 | May 5, 2009 |

| 100 | Jul. 6, 2010 | May 29, 2012 |

| 53 | May 3, 2016 | May 2, 2017 |

| 43 | Oct. 26, 2021 | Aug. 16, 2022 |

In hindsight, what stands out about this drought? To put it succinctly: its stubbornness but overall lack of severity.

Drought was present in all four seasons over the past year. It first emerged during our dry fall before improving – although not totally disappearing – in the winter. The spring saw an expansion across the Coastal Plain, and then summer showers eventually eroded it away.

One of its main impacts was the November fire season in the northwest Piedmont, including the 1,000-acre Grindstone Fire on Pilot Mountain. As dry conditions set in this spring, the corn crop also took a hit and may not full recover during this growing season. Just last week, 37% of corn was rated in poor or very poor condition, and Extension agents in Union County say this year’s corn yield there could be half as much as usual.

However, we never saw broad-scale crop damage – most cotton, soybeans, and tobacco are in good shape at the moment – or widespread water supply disruptions as in some past extended droughts.

That largely came down to two factors. First, we never reached worse than Severe Drought, or D2 on the US Drought Monitor’s four-category drought scale. In all four of our longer-lived droughts since 2000, parts of the state were classified in Extreme (D3) or Exceptional (D4) Drought, which tend to cause worse and more entrenched impacts.

Second, drought was largely confined to the Sandhills and Coastal Plain. Even at its broadest extent last December, the southern Mountains avoided any drought classification, and precipitation during the winter and spring was generally sufficient to keep the Piedmont on the fringes of drought and its impacts.

We certainly can’t rule out a drought re-emergence if some spots dry out this fall, and Abnormally Dry (D0) areas remain where summer rainfall and streamflows have been below normal. However, the good news is that the summer brought overall improvements – and not degradations – to our statewide drought situation.

The Calm Before the Storms?

The disappearance of drought was a bit surprising considering we didn’t have any rain contribution from tropical storms last month. That lack of recent activity in the Atlantic has surprised even experts who predicted a prolific hurricane season this year.

“They’re totally flummoxed,” said Dr. Carl Schreck, an expert in tropical climate at the North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies in Asheville. “By all accounts, August should have been active.”

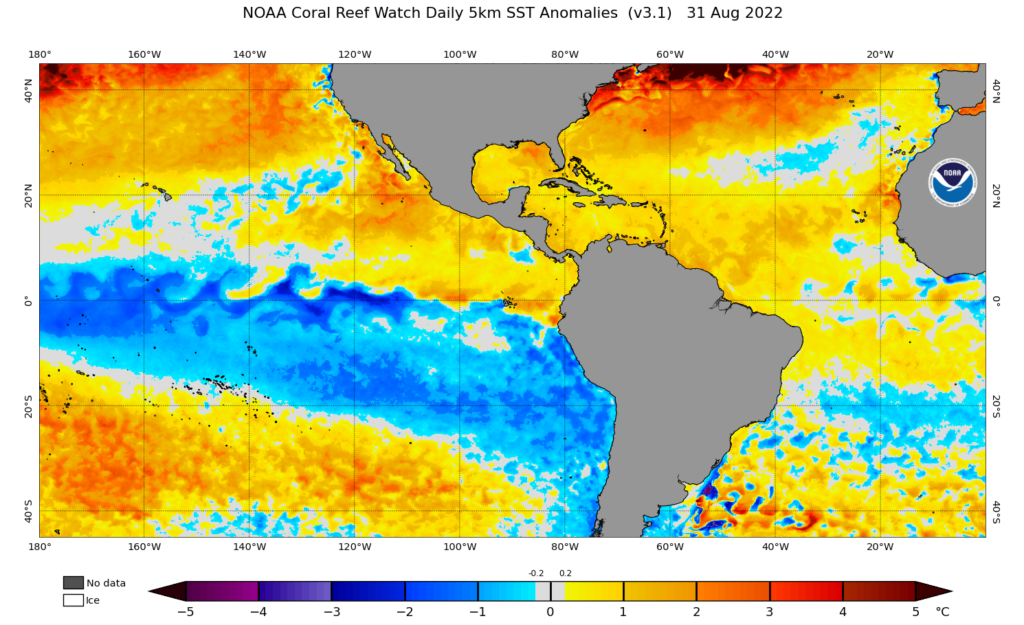

There were – and still are – good reasons for that expectation of an active season. For one, sea surface temperatures across the Atlantic have been warmer than normal this summer, including across the main development region from the coast of Africa through the Caribbean, and in the Gulf Stream along our east coast.

La Niña conditions remain in place, and the weaker upper-level westerly winds associated with those events tend to decrease wind shear across the Atlantic and make it easier for storms to form. That’s just one part of a broadly favorable wind pattern in the basin.

“Tropical winds are all about in, up, and out,” said Schreck. “Air is generally rising over the Atlantic and Africa, and those areas have been at least marginally wetter than normal.”

While plumes of dust carried from the Sahara Desert inhibited potential activity in July, August had generally more favorable environmental conditions – but still no tropical storms. The main missing ingredient was vertical instability, which can initiate the thunderstorm clusters that often develop into tropical systems.

As a result, it was only the third August since 1950 with no named storms in the Atlantic, joining 1961 and 1997. And prior to the development of Tropical Storm Danielle on September 1, we went 60 consecutive days since the last named storm – Tropical Storm Colin, which briefly skirted our coast in early July.

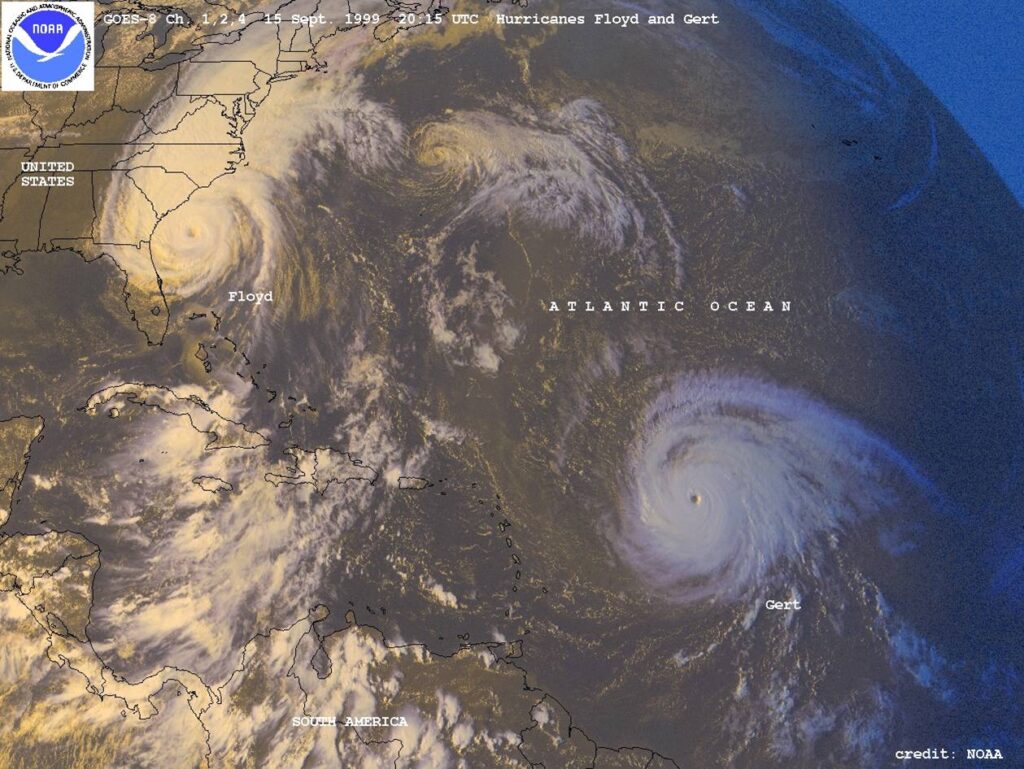

That was the longest gap between named storms during hurricane season since 1999. Of course, that year offers a memorable lesson for why we shouldn’t let our guard down, despite the lack of activity so far this season.

During a two-week period in September 1999, two hurricanes – first Dennis, then Floyd – each drenched eastern North Carolina, and their aftermath saw historic inland and freshwater flooding along the Tar, Neuse, and Cape Fear rivers.

While that’s no guarantee we’ll have similar storms this year, it is a reminder that an impactful – and even above-normal – hurricane season is still possible now that we’re seeing more disturbances crossing the Atlantic.

The typical peak of hurricane season may be in mid-September, but the activity may be just beginning at that point this year. So get prepared and stay alert, because the tropics are finally heating up.