The dog days were downright dreadful this year, as part of an early-starting summer that rarely offered much relief, at least until last weekend. Statewide, this June and July combined were our 12th-warmest beginning to summer since 1895, and the warmest since 2016.

The heat wasn’t just isolated here in North Carolina. To the west, our colleagues at the Oklahoma Mesonet noted an arduous achievement on July 19, when all 120 of their weather stations hit at least 102°F.

Of course, we’re shielded from such statewide coverage of triple-digit extremes thanks to the cooler climates in our Mountains and along the coastline, as we described in our Curious Coast blog post series.

But it did make us wonder: has our entire state ever been above, say, 80 degrees at the same time?

In this edition of Climate Curiosities, we’re on the hunt for the warmest hour ever across North Carolina.

Our Warmest Recent Hours

An obvious starting point for our search is Mount Mitchell – our state’s highest peak, and often, the low bar for temperatures across the state.

With a climate more similar to southern Ontario than the southeastern United States, Mount Mitchell’s average summertime high temperatures, in the mid-60s, are cooler than the average lows across most of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain.

That means the best candidates for our warmest hours will come from the small subset of Mount Mitchell’s extreme hottest days.

Our ECONet station on Mount Mitchell began making hourly observations in late June 2008, and in the 14 years since then, its highest instantaneous temperature is 81.3°F at 2:49 pm on July 1, 2012. However, the temperature there dropped a few degrees by the 3 o’clock hour, and in any case, Mount Mitchell was not the coolest spot in the state at that time, as rain showers in the northern Piedmont left Oxford at just 73°F, with the nearby Henderson-Oxford Airport at 77°F.

On the previous afternoon, though, we find our warmest hour in the era of hourly observations. At 6 pm on June 30, 2012, Mount Mitchell was at 78.8°F while Grandfather Mountain, located 33 miles to the northeast, measured an hourly temperature of 78.6°F at the mile-high swinging bridge.

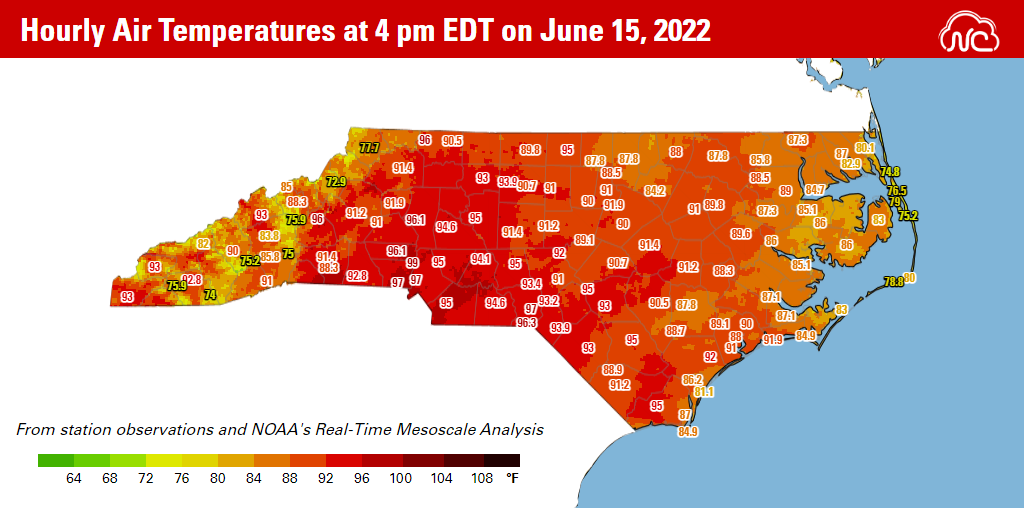

This summer, our warmest hour was on June 15 at 4 pm. At that time, Grandfather Mountain reported a temperature of 72.9°F, while our other high-elevation sites including Mount Mitchell and Highands were sitting at 74°F or greater.

A few Outer Banks sites also reported cooler temperatures, including 74.8°F in Duck and 75.2°F at Oregon Inlet, but in between, most of the state was solidly in the upper 80s or low 90s on that mid-June afternoon.

While those June days from 2012 and 2022 were warm for sure, neither quite met the criteria for the entire state rising above 80 degrees all at once. However, by digging deeper into the past, we can find more possibilities of such an occurrence.

Searching the Daily Records

Since 1925, and aside from a roughly 15-year gap in its data between 1965 and 1980, a National Weather Service Cooperative Observer station on Mount Mitchell has made daily temperature and precipitation observations.

This location has measured multiple state records, including our coldest temperature (-34°F on January 21, 1985), greatest single-storm snowfall (50 inches in March 1993), and wettest calendar year (139.94 inches in 2018).

The current Mount Mitchell observing site and its predecessor have reported daily maximum temperatures of at least 80 degrees on 15 occasions, which helps narrow down the days to consider.

Of course, it’s not the only site that could scuttle a potentially hot hour. As we’ve already seen in more recent examples, depending on factors such as cloud cover and wind direction, other mountain sites can be even cooler than Mount Mitchell, while scattered showers or the sea breeze can drop temperatures across other parts of the state.

Our search becomes even trickier because we don’t have long-term daily observations from many of these mountaintop or immediate coastal sites. Instead, we’ll have to use clues offered by nearby stations.

For instance, Grandfather Mountain tends to run 7 to 10 degrees cooler than Boone and 4 to 6 degrees cooler than Banner Elk, where we do have long-term historical observations, while Wayah Bald Mountain is often 10 to 15 degrees cooler than lower-elevation Cullowhee and Franklin.

That means we’ll need to look for days when these nearby observing sites were well into the 90s, which should almost ensure that the mountain peaks were in the 80s.

After applying that logic and searching historical records from across the state, we’re left with a top candidate from almost a century ago.

Our Warmest Historical Hour?

From 1925 to 1927, the Carolinas were deep in drought nearly a decade before the better-known Dust Bowl era in the Midwest.

It was a challenging time for farmers, already struggling to sustain profits after World War I-era subsidies had ended and European farms reemerged in the global market. Adding to local farmers’ issues was the emergence of the boll weevil, a pest that devastated the cotton crop. The drought was yet another challenge, and it effectively wiped out three straight growing seasons’ worth of productivity.

That drought was also a key part of raising temperatures, even after the end of the climatological summer. As surface water sources such as soils and streams dried up, less moisture could evaporate from them to form water vapor, or the humidity that often moderates our climate compared to areas like Oklahoma.

By early September in 1925, a broad area of high pressure over the Deep South sent temperatures soaring beyond 100 degrees, and that warm air infiltrated western North Carolina. Even mountainous Marshall climbed to 100°F on September 8, which remains the latest in the year that location has ever reached triple digits.

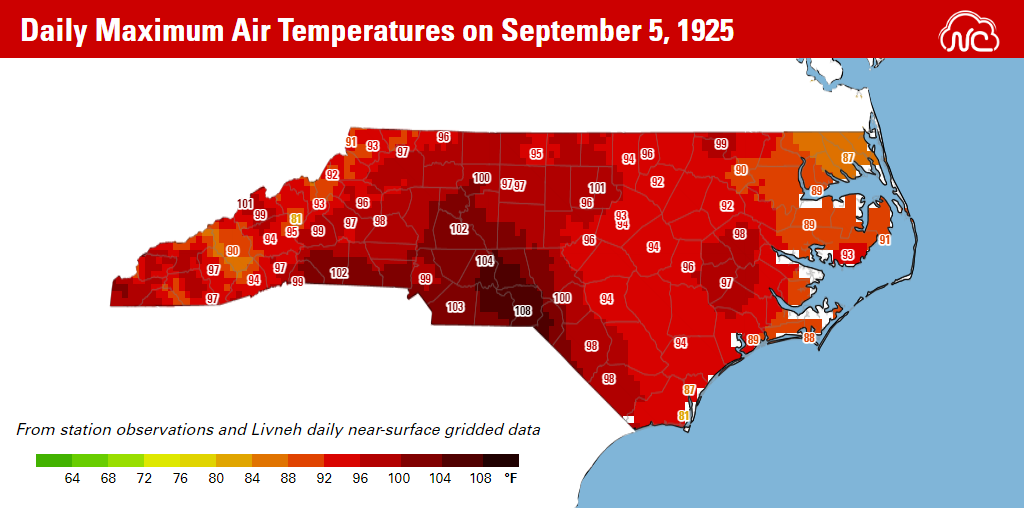

Three days earlier on September 5, Mount Mitchell hit a high of 81°F under clear skies. In Ashe County, Parker reached 91°F, and the observer there noted in the monthly remarks that it was the “hottest September ever known in this section.” Statewide, September 1925 still ranks as the 2nd-warmest on record.

Elsewhere in the Mountains, high temperatures on September 5 topped out at 92°F in Banner Elk and 97°F in Cullowhee with smoky skies. That local observer reported “all crops greatly cut short by drought” in September, with “springs low and streams lowest ever known”.

Given the widespread warmth in the western part of the state, it’s likely that peaks such as Grandfather Mountain were at least in the low 80s. In addition, a second area of high pressure developing over eastern North Carolina limited pop-up shower and thunderstorm activity. The coolest coastal site in Southport still reached 81°F that day.

Since temperatures in early September tend to max out between 2 and 4 pm, we’ll consider September 5, 1925, at 3 pm the most likely time for our state’s warmest hour, with perhaps all of North Carolina rising above 80 degrees for a brief period that afternoon.

If it didn’t happen then, it had another chance the following day, as Mount Mitchell again hit 81°F and all other observing sites across the state reported maximum temperatures of 85°F or greater on September 6.

Overall, the combined effects of an entrenched drought, a sweltering air mass building from the west, and cloudless skies made for a pair of especially oppressive afternoons 97 years ago. On those early September days in 1925, there was little relief to be found from the heat, no matter where in the state you went.

And while our warmest hours occurred under exceptional circumstances almost a century ago, North Carolina continues to warm today. The North Carolina Climate Science Report noted few historical trends in our daytime highs, but an upward trend in nighttime low temperatures, which poses an increasing public health risk.

Additionally, in the near-century since 1925, we’ve undoubtedly had some hot summer days, including our state record high of 110°F on August 21, 1983; Raleigh’s local record of 105°F, tied four times since 2007; and our rare early October hundred-degree heat in 2019.

For its persistence alone, 2022 also deserves a mention among our warmest periods. As of August 15, Raleigh has recorded 61 days with temperatures at or above 90 degrees in 2022, which is its 3rd-most at this point in a calendar year, and just two days behind the sweltering pace set in 2010.

In the future, climate models show that both daytime and nighttime temperatures will increase across the state, including in the Mountains, which could see three to six times as many hot days per year, with temperatures reaching at least 90°F, by mid-century.

With those changes in mind, our next potential warmest hour could be on the horizon.