Amid our worst fall fire season in five years, two wildfires in the past month have stood out from their elevated perches atop the Piedmont’s highest peaks.

On November 9-14, a wildfire burned 40 acres on Sauratown Mountain in Stokes County, and an even larger blaze started last Saturday on Pilot Mountain in Surry County. Called the Grindstone Fire because of its source near the Grindstone Trail, it has burned more than 500 acres at Pilot Mountain State Park and could eventually cover more than 900 acres, according to the NC Forest Service.

These two fires are symptomatic of a recent lack of rainfall and expanding drought, which currently covers almost half of North Carolina. However, other local and seasonal environmental factors have also spurred on these particular fires in the same part of the state.

A Dry Fall

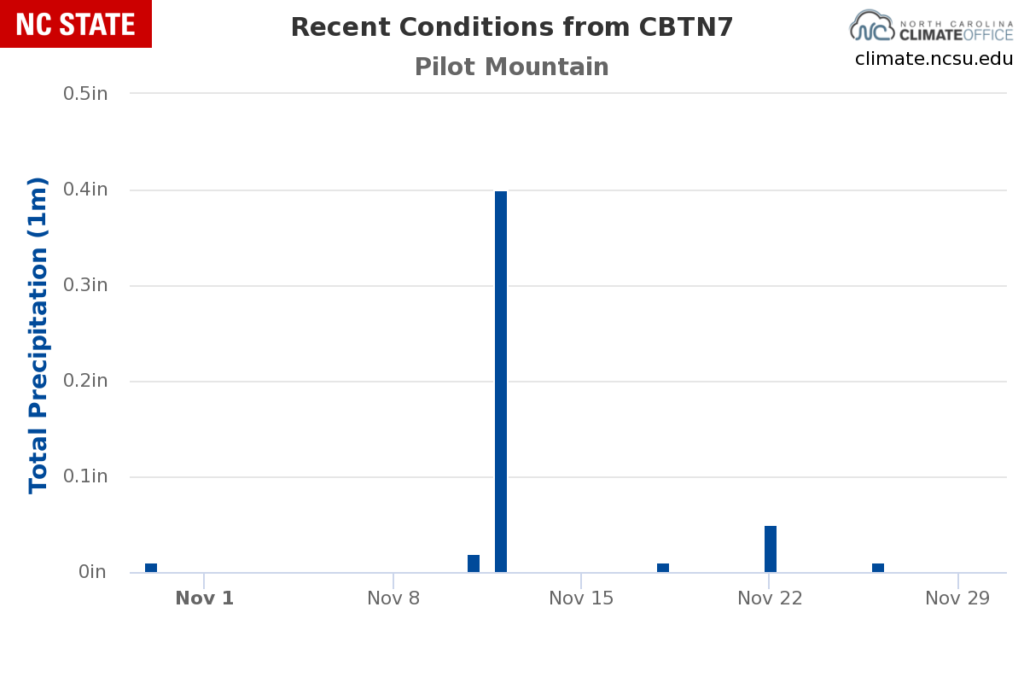

Our transition from a wet summer into a decidedly drier fall was an abrupt one. At Pilot Mountain, the NC Forest Service’s automated weather station recorded 4.13 inches of rain in a single event on September 22-23, on the heels of an August with more than 5 inches of total rainfall.

In the more than two months since that late-September event, only 1.9 inches of rain has fallen there, and each successive day, week, and month seems to be drier than the one before it. Just 0.49 inches of rain has fallen at Pilot Mountain so far in November, with only 0.07 inches since November 12.

While that part of the state is not yet classified in Moderate Drought (D1) on the US Drought Monitor, the extreme short-term dryness has still been enough to prime the landscape for wildfire activity.

A Killing Freeze

Temperatures have played a role as well. After the first freeze of the season at Pilot Mountain on November 4, fine ground-level vegetation — such as roadside grasses, rhododendron, mountain laurel, and holly — returned to dormancy and became highly flammable kindling during the dry days over the past few weeks.

By contrast, eastern North Carolina saw its first freeze almost two weeks later on November 16, so dormant vegetation in that area hasn’t had as long to dry out as it did across the northwest Piedmont.

Even still, some fires are already popping up in eastern North Carolina. Last week, a single fire burned 140 acres in Columbus County and multiple fires have each burned 20 acres or more in the Sandhills.

Terrain Trickery

The elevation of western North Carolina induces some interesting environmental effects that have also helped these fires grow.

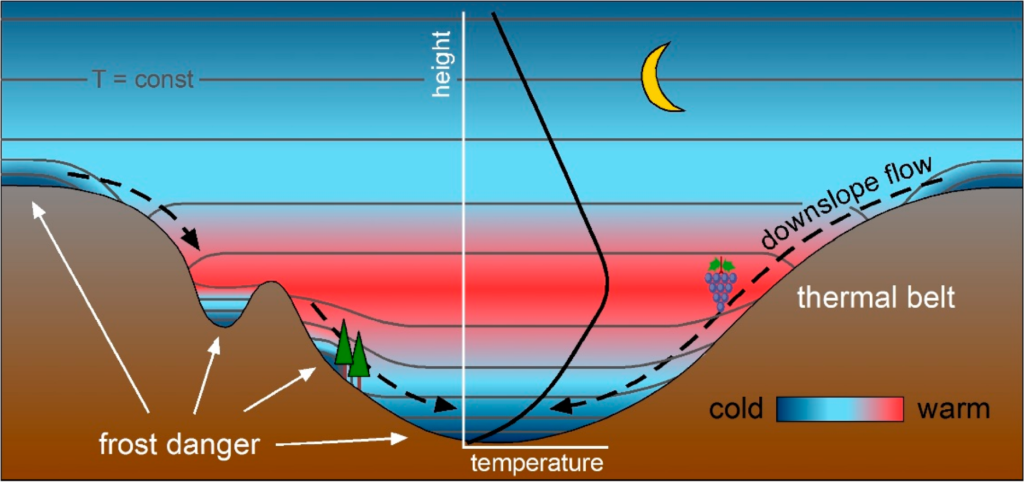

On clear nights, a heat exchange takes place along the mountainsides. Cooler air from the upper slopes drains downhill, while the warm ground down below radiates its stored energy upward. That creates features called thermal belts on the middle third of mountain slopes, where this escaping heat is trapped.

Within these belts, overnight temperatures remain warmer with lower humidity, which can keep fires like those on Sauratown and Pilot mountains burning all day long.

Whipping Winds

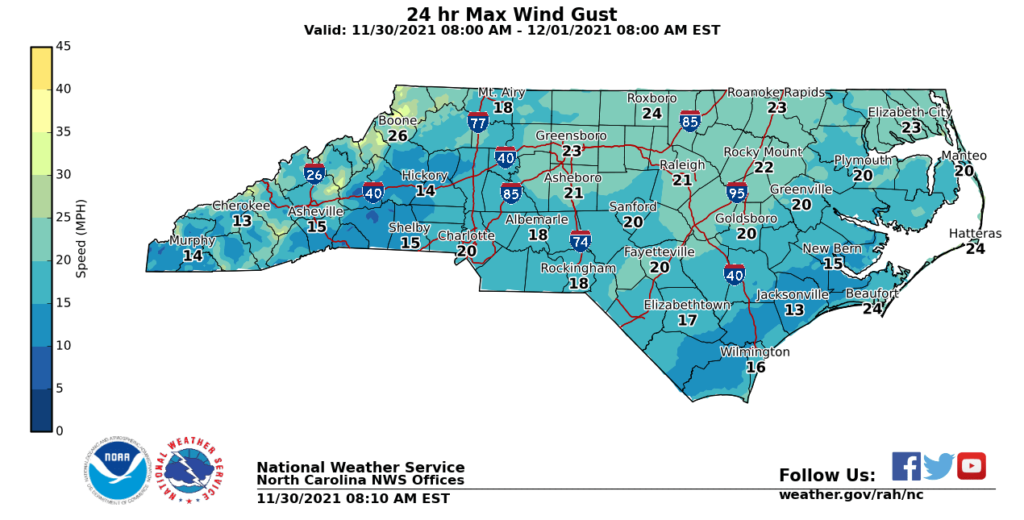

Today is set to be the windiest day of the month, which means fires could spread rapidly. Statewide, wind gusts of more than 15 mph are likely, with maximum gusts exceeding 20 mph in parts of the Mountains and northern Piedmont.

As a result, the NC Forest Service has issued a statewide burning ban effective at 5 pm last night until further notice. It prohibits the open burning of leaves, branches or other plant material, including campfires.

Along with limiting the start and spread of new fires, the burn ban should help crews and resources focus on controlling the Grindstone fire as it encompasses more of Pilot Mountain.

An Initial Spark

Historically, lightning is responsible for only about 2% of wildfires in North Carolina. That means the vast majority are caused by human ignition sources.

That was the case with the Sauratown Mountain fire, which started from an unextinguished campfire. The cause of the Pilot Mountain fire is unknown, but an investigation will be conducted once it’s under control.

Even if unintentional, those sparks have spread quickly among the dead vegetation and fallen leaves. In some spots, the seasonal leaf drop started early this year due to the dry weather. In others, it happened a bit later than usual thanks to our warm October.

By now, though, most leaves are off the trees and covering the ground, which has added to the fuel loading. On Sauratown Mountain, leaves falling along the perimeter of the fire containment lines have even fueled some reburns in recent weeks.

A Fiery Fall

The past few years have mostly been awash with fall rainfall. In 2020, a half-dozen remnant tropical storms soaked the state through mid-November, while fall 2019 began with a drenching from Hurricane Dorian and 2018 was marked by the record-setting rain from Hurricane Florence.

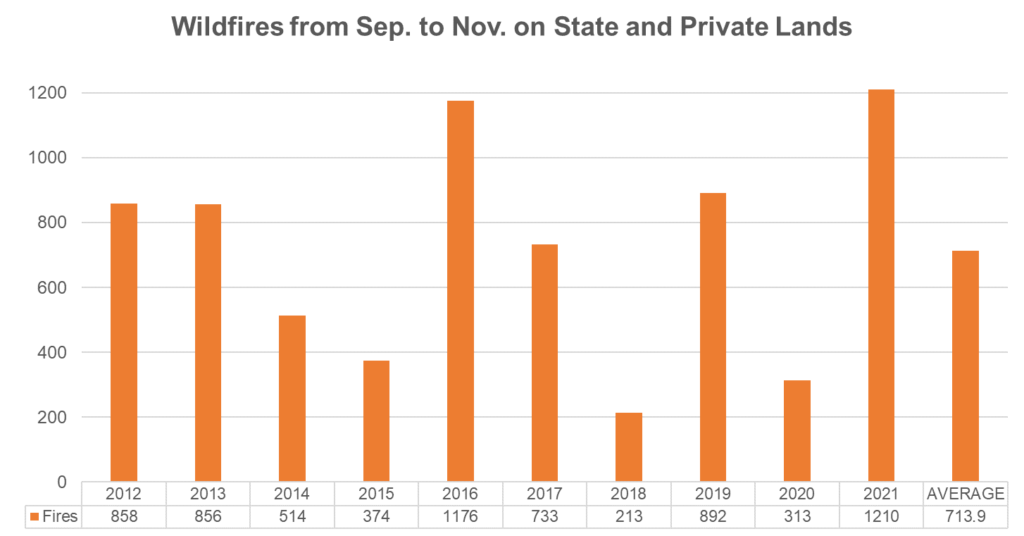

To find another active fall fire season, we have to go back to 2016, when eastern North Carolina was underwater after Hurricane Matthew but the southern Mountains descended into extreme drought.

Although 2016 featured more large wildfires than this year, most of those were on federally owned lands, including the 14,000-acre Tellico Fire in Swain County.

Counting only wildfires on state or private lands, 2021 narrowly edges 2016 as our most active fall fire season in the past decade. Since September 1, the NC Forest Service reports 1,210 fires burning 2,693 acres — and growing — across the state..

While the 2016 drought was more severe at this point in the season, that December also started with several inches of needed rainfall. By contrast, our forecast shows more dry days in store and a December outlook tilted toward below-normal precipitation, consistent with the ongoing La Nina pattern.

That means the fire season won’t end with the final day of climatological fall, and Smokey the Bear — along with the state and local forestry and fire crews — will stay busy heading into the winter.