Parts of North Carolina’s coast offer the opportunity for a rare view, at least within the continental United States.

Along the narrow Outer Banks, gazing through the seagrass and beyond the sandy shore, you can watch the sun rise along the eastern horizon, glistening in the waves that roil the Atlantic Ocean.

Later that day on the sound side of our barrier islands, you can watch the same sun set in the west over an uninterrupted stretch of calm but churning water.

The chance to see the sun rise and set over water at the same location is one of the many unique features of our Coastal Plain, and one that highlights both its charm and its vulnerability – surrounded by water, and in some spots, now being overtaken by it.

In partnership with NC State’s Coastal Resilience and Sustainability Initiative, and after conducting interviews with more than a dozen experts whose work has helped them understand the characteristics and challenges of eastern North Carolina, we’re sharing the story of our state’s Coastal Plain region in a five-part blog post series beginning today.

Join us over the next two weeks as we explore our curious coast.

Other Posts: Soils and Agriculture | Ocean and Coastline | Rivers and Wetlands | Adaptation and Resilience

Defining the Coastal Plain

For Dr. Ryan Emanuel, associate professor in Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment who grew up in eastern North Carolina, those soundside views are one of many reasons why he loves that part of the state. When his own children were younger, he took them to Jockey’s Ridge State Park, and they’d venture into the seemingly endless shallows of the Pamlico Sound together.

There’s something special, he said, about “being able to walk out hundreds of yards and only have water up to your shins.”

The sounds and the Outer Banks that encircle them define the eastern edge of the region, but it also extends more than 100 miles inland in some spots, encompassing what we call the Coastal Plain.

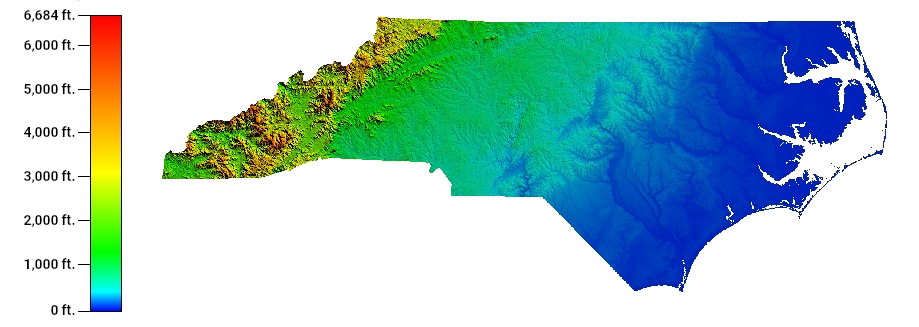

That name alone says a lot about what it is: coastal, because it’s adjacent to the ocean; a plain, because it’s broad, flat land that gradually decreases in elevation until it dips beneath the waves at the ever-shifting shoreline.

Around the world, coastal plains are found in areas like the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States, on either side of the Indian subcontinent, and on the east coast of Australia. But you won’t find them everywhere land meets water.

“Just because you’re up against an ocean, it doesn’t mean you’re going to have a coastal plain,” said Dr. Reide Corbett, executive director of the Coastal Studies Institute, whose office on Roanoke Island overlooks the Croatan Sound.

In the western US, the landscape is much more rugged, with a sharp dropoff of land into the ocean. Corbett said that makes it more like a “coastal range,” and from California through Alaska, mountains thousands of feet tall rise up within view of the Pacific.

Compare that to the gradually sloping continental shelf across eastern North Carolina, with an elevation change of only 100 feet between Fayetteville and Wilmington, and it makes for a very different coastal landscape.

“About 45% of our land in North Carolina is in the Coastal Plain,” said Corbett. “That’s a huge swath of North Carolina that’s a coastal plain.”

For North Carolina and the rest of the southern Atlantic coast, our wide expanses of low-lying land and their history tells the story of a region defined by the water – and often, submerged beneath it.

What is now the Coastal Plain was once a prehistoric ocean floor, extending all the way to its western boundary. Today, that ancient high-water mark is called the fall line since the elevation change there is so abrupt that rivers flowing over it spill down waterfalls at places like Carvers Creek in Fayetteville and Roanoke Rapids – so named for the local roughness of the Roanoke River.

As sea levels receded millions of years ago, the coastline shifted eastward and exposed what’s now the bedrock of our Coastal Plain. Since then, it has been covered by sediments carried down and deposited by the rivers that run through it.

Dr. Barbara Doll, an extension associate professor in NC State’s Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, said that process continues to link the Coastal Plain with our other two ecoregions, the Mountains and Piedmont.

Since they’re connected to the coast via the rivers, a portion of their landscapes, long since eroded and swept downstream, now makes up the very ground we walk on, drive on, and plant in across eastern North Carolina.

“It’s loved by many,” she said, “and not just the people that are there.”

Whether it’s viewed as a vacation destination at our beaches, a seafood supplier just offshore, a habitat for many unique plant and animal species, a site of long-held cultural significance, or the first line of defense against tropical storms, the Coastal Plain is a place of importance for people all across North Carolina.

How the Coast Shapes Our Climate

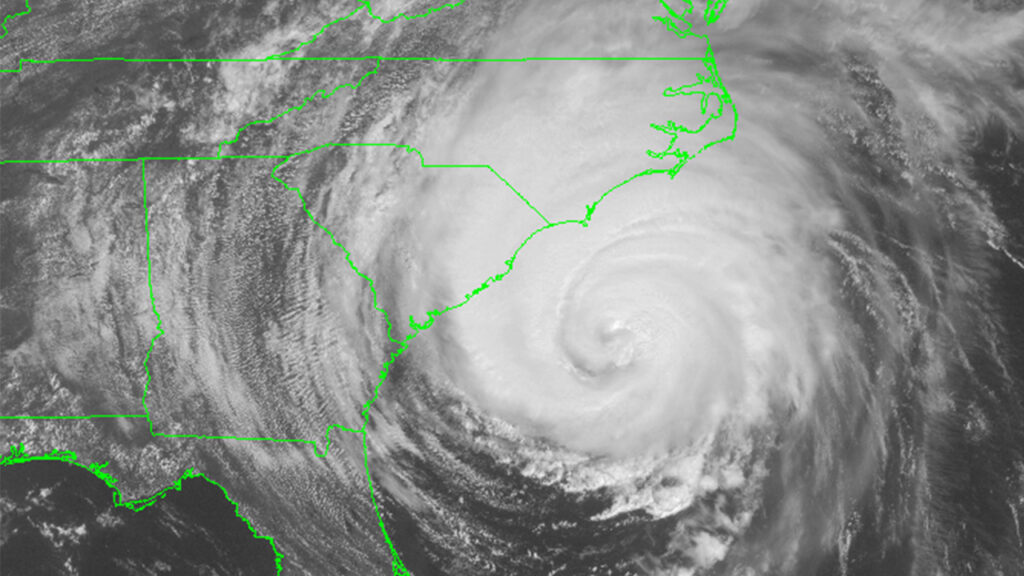

When you look at a map, the one thing that sticks out about eastern North Carolina is – well, how much it sticks out. From the point where our southern coastline begins along the South Carolina border at Calabash, the land bulges 175 miles to reach our easternmost point on Hatteras Island.

That has one obvious effect on our climate: it makes the Coastal Plain an easy target for tropical storms and hurricanes heading up the East Coast.

Storms like Fran and Floyd famously intersected our state as they raced northward, while the concave shape between the capes along our coastline acted like nets to catch westward-moving hurricanes such as Isabel and Florence.

That has made parts of our coast twice as likely to see a landfalling hurricane as more southerly yet geographically sheltered sites such as Savannah, GA, and up to three times more likely than the Chesapeake Bay to our north, since we often absorb the brunt of the impacts from storms heading in that direction.

Likewise during the wintertime, extratropical storms or Nor’easters strengthening over the warm offshore waters can bring gusty winds and heavy precipitation to our coast where it juts out into the Atlantic. When cold air dips far enough south and east, these areas can even see heavy snowfall, as in the Christmas blizzard of 1989.

Hurricanes and Nor’easters aren’t the only way that our coastline affects our climate. Another phenomenon happens almost daily during the summertime, and it’s the result of the interplay between our coast and the surrounding water.

As the land heats up during our hot summer afternoons, warm air rises to cool and creates an area of relatively low pressure near the ground. Cooler air originating over the ocean then moves inland and provides the moisture needed to form clouds, showers, and thunderstorms.

The result is the sea breeze, and at the beach, it can offer a few hours of cooling relief, if not an unexpected downpour. On rare days with a particularly strong southeasterly wind pattern, the sea breeze front has been known to make it across almost the entire Coastal Plain, nearly reaching Raleigh.

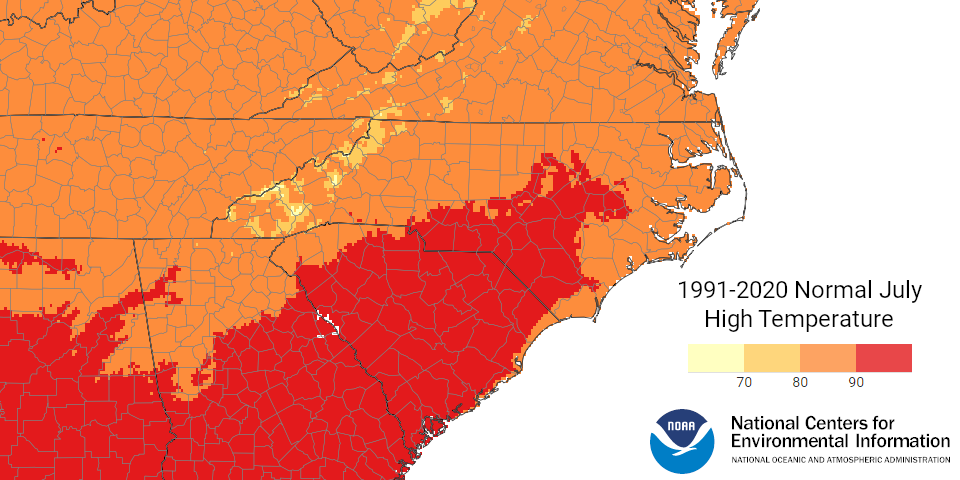

A final climatic consequence of our coastal geography is the warmer weather that typically occurs there. Average high temperatures in July, our hottest month, reach the low 90s across the southern and central Coastal Plain, thanks to its more southerly location with an assist from the fast-heating sandy soils.

The immediate coastline isn’t quite as hot due to the moderating effect of the nearby ocean. The average July high temperature at Hatteras (87.3°F) is more than 3 degrees cooler than in the inland city of Greenville (90.4°F).

It’s another curious part of our coast, and another reminder of the power and ever-presence of water in that region.

How the Climate Shapes Our Coast

The sorts of weather events that we see across the Coastal Plain – in some cases, due to its shape and location relative to the conveyor belt for storms that runs along the East Coast – can also have a physical impact, not to mention a financial one.

Historically, this has been most obvious along the Outer Banks after hits by hurricanes. Their winds and waves can carve up those delicate barrier islands, reshaping the land for better or (more commonly) for worse.

This is perhaps most obvious on the northern end of Hatteras Island where it meets – or doesn’t meet, depending on the time – Pea Island. The two islands were separate for nearly two centuries until 1922, when a steady influx of sediment eventually joined them together. A hurricane in 1933 re-opened the inlet between them, but it naturally filled in again by 1945.

Most recently, Hurricane Irene in 2011 gouged another inlet just north of Rodanthe, temporarily cutting off access to Hatteras Island via Highway 12. As the latest attempted workaround for this shifting stretch of land, the so-called Jug Handle Bridge is set to open this summer, largely bypassing this section of volatile coastline that can’t seem to decide if it’s one island or two.

Even inland, our weather and climate can affect the landscape and how we use it, especially as storm events produce heavy rainfall and flooding that in some areas has nowhere to go but into towns, farms, and neighborhoods.

“When you have such a broad, flat area, the impact associated with river flooding, storm surge, and sea level rise is going to be felt way inland,” said Corbett.

Beginning with Floyd in 1999 and continuing with Matthew in 2016 and Florence in 2018, we have now seen three hurricanes produce significant freshwater flooding in the span of less than 25 years. The compound impacts from these repeated events have forced landowners in low-lying or riverine areas to rethink where they live and how they use this land.

“In eastern North Carolina especially, they see the neighborhoods that are getting flooded time after time, even if they’re not in the floodplain,” said Andrea Webster, resilience policy advisor for the NC Office of Recovery & Resiliency, which is working with coastal communities to identify and address their vulnerabilities following our recent flood events.

After Floyd, 42 hog farms located in floodplains were bought out to avert another ecological disaster of animal waste breaching storage lagoons and contaminating rivers and water supplies. Since Matthew and Florence, local governments have received more than $130 million in grant money from FEMA to rebuild, elevate, or buyout properties damaged by these flood events.

For nearly anyone who lives in the Coastal Plain, these recent storms have been a jarring reminder of their precarious coexistence with the water all around them – and how additional water falling from above or rising from below can put their own livelihoods at risk, no matter how long they’ve been there.

A Home for Humans

The very water that’s now seen as so threatening has historically been a major reason that civilizations in our Coastal Plain have settled there and succeeded.

Dr. Emanuel should know. As a member of the Lumbee Tribe from southeastern North Carolina, he has a deep appreciation for where Indigenous people have lived, how they have experienced past and present threats to their culture, and what the future may hold.

Even in the remotest parts of Robeson County, Emanuel said, there is a deep history of human habitation dating back 6,000 to 10,000 years, in some spots surrounding the curious features called Carolina bays – small inland bodies of water, disconnected from rivers, that dot the terrain.

“Today, they are just wetlands or impressions in the earth, but they were once huge lakes, and we have archeological signs that people lived on their beaches in fishing communities,” he said.

By the 17th century, European settlers had arrived in North Carolina, and they used major rivers like the Cape Fear, Neuse, and Roanoke for transportation: “conduits of people, ideas, and goods moving from the coast inland,” added Emanuel.

That occasionally meant conflict with Indigenous communities, but some Native peoples, including the ancestors of the Lumbee Tribe, were largely ignored, again thanks to a quirk of the Coastal Plain.

“Robeson County was a literal backwater in the march of colonialism because it wasn’t easily accessible by river,” said Emanuel.

Settlers eventually came across ancestors of Coharie and Lumbee people. In some areas they were forcibly removed, while in other spots, they were left alone. That revealed the priorities of the colonizers, who viewed the lands as worthless and unsuitable for transportation, agriculture, or communities, despite the rich history of civilization there.

For the Lumbee, it’s the only land they’ve known, which makes it worth protecting and preserving, especially as new threats emerge.

“It’s the place that we come from,” said Emanuel. “We have no old country to look to wistfully when we think about our ancestors or where our roots are. We live in the old country and that’s what makes it special.”

The cultural value of communities is true for other areas as well. The town of Princeville was originally founded as Freedom Hill by formerly enslaved people in 1865. But its location within the Tar River’s floodplain is not ideal – nor was it an accident.

“Right after the Civil War ended and slavery was over, white people didn’t want us to move too far away so they could still use us for labor, so they gave us land that was worthless,” said Bobbie Jones, the current mayor of Princeville.

One of Princeville’s greatest hardships came after Hurricane Floyd in 1999. The flooding overtopped a levee and inundated the town with 23 feet of water.

The resolve of the people of Princeville to recover and rebuild is a common one across eastern North Carolina, according to Dr. Cindy Grace-McCaskey, an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at East Carolina University. She has seen the same strong connections to family and ancestral lands in other areas.

“In Hyde County, the people who worked the land ended up being pushed to the periphery because that’s what was available to them,” she said. “That land is sacred to people. It’s so special not only to the community, but it should be special to all of us.”

In eastern North Carolina, economically disadvantaged and minoritized populations, such as Black and Indigenous communities of color, have felt the impacts of extreme weather and climate more potently than most.

Floyd devastated Princeville. Matthew and Florence sent the Lumbee River (its original name, before state officials changed it to the “Lumber” in 1809) to record high levels with floods never before seen in their civilization. And Hyde County is now under assault from sea level rise, flooding up to 200 days per year.

To the groups experiencing those events, they are clear signs that the climate is changing.

Some changes, such as warming temperatures and more frequent extreme heat, are at least predictable in their progression, although they’re still shifting natural features such as plant hardiness zones and insect ranges that the Lumbee have understood for centuries.

The changes in precipitation – including its increased variability, from wetter storms to faster-emerging droughts – are difficult to plan for and adjust to. And that shouldn’t only concern Lumbee members such as Emanuel, Princeville leaders like Jones, or fourth-generation farmers in Hyde County.

“It’s a terrible problem, not just for planners or managers, but anybody who has to live in a landscape with water on both sides,” said Emanuel.

By its very definition, throughout its history, and because of its climate, the Coastal Plain of North Carolina is intertwined with water, and that shows no signs of changing.