If this blog post series so far has taught us anything, it’s that in North Carolina’s Coastal Plain, the land has always been in a delicate dance with water, from the sea’s retreat millions of years ago through the carving and shifting of our coastal rivers over hundreds of thousands of years to the erosion and accretion of sand and sediments along the shoreline that we can see happening today.

As these changes continue and accelerate together with the warming climate, they’re making our permanent human settlements appear all the more temporary in some places, and forcing people across the state to consider what the changing coast means for all of us.

To wrap up this series created in partnership with NC State’s Coastal Resilience and Sustainability Initiative, we’re looking today at the sort of changes facing eastern North Carolina, the impacts they’re seeing, and mitigation efforts already being put in place.

We’ll finish with thoughts about resilience in the Coastal Plain for years to come – both in terms of how it may look, and how we may need to think about it to secure our own future there.

Climate Changes for the Coast

The Coastal Plain is already feeling the effects of climate change, driven by increased concentrations of greenhouse gases. These gases act like a blanket, trapping more heat from the sun in our planet’s lower atmosphere and shifting the earth’s energy balance, along with the carbon cycle and water cycle.

As the North Carolina Climate Science Report notes, temperatures across the Coastal Plain have been steadily rising over the past five decades. So far this century, 20 out of 21 years have been warmer than the historical average within the region.

By 2050, annual average temperatures are expected to warm by an additional 2 to 5 degrees, with a mid-range estimate of an additional 6 to 10 degrees of warming possible by 2100 if global emissions remain at their current levels.

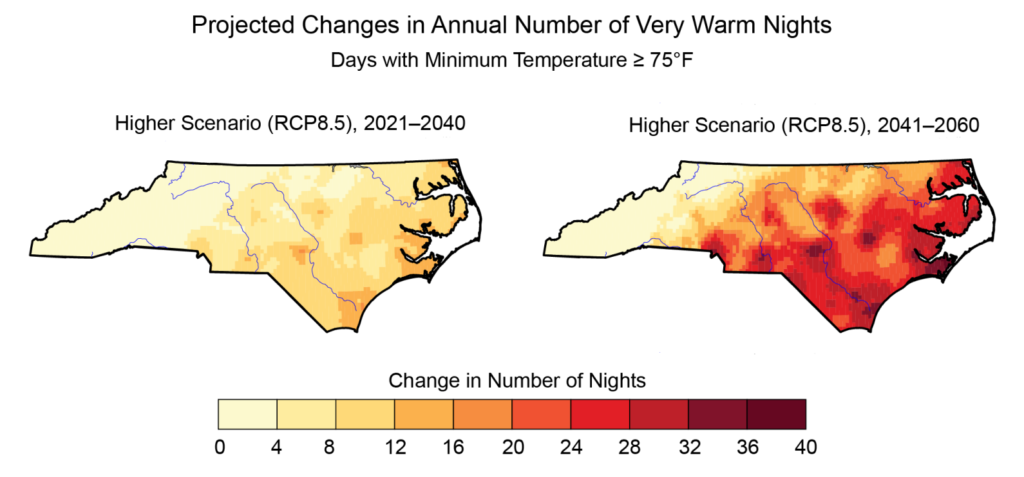

Of particular concern are the increasing frequencies of very hot days and very warm nights, when temperatures reach at least 95°F and never fall below 75°F, respectively. The long-term historical averages show 13 very hot days and 6 very warm nights per year across the Coastal Plain.

By the end of the century, both are expected to become at least twice as common, and climate models using current emissions levels show an increase of between 48 and 87 very warm nights per year – which could mean effectively the entire summer season spent above 75°F.

For centuries, scientists have known that a warmer atmosphere tends to be a wetter one. The Clausius–Clapeyron relationship states that for every 1°C or 1.8°F of warming, the water-holding capacity of the atmosphere increases by about 7%.

Those fundamental physics are now playing out across the Coastal Plain. Most climate models predict annual average precipitation will increase in the future, but the way in which that precipitation falls is also changing.

More rain is increasingly concentrated into fewer events, meaning wet days are getting wetter and dry spells will dry out even more quickly, especially in combination with warming temperatures.

Nowhere did the reality of our wetter climate hit harder than in the town of Princeville in September 1999. Two heavy rain events less than two weeks apart from hurricanes Dennis and Floyd sent the Tar River to record high levels, overtopping a dike and inundating the predominantly Black town.

Despite warnings from the US Army Corps of Engineers as the river rose, few in the town were prepared for a disaster of the magnitude that occurred.

“I remember it well. They were telling us the flood was coming, and myself along with everybody else was in disbelief,” said current Princeville mayor Bobbie Jones. “It took the floodwaters coming to my house and them lifting me up by helicopter [to realize how bad it was].”

The flooding after Floyd, and more recently from Matthew in 2016 and Florence in 2018, has devastated wide swaths of the Coastal Plain, and each event has the fingerprints of climate change all over it.

“We know why this is happening, because the storms are slower and they hold more moisture,” said Dr. Ryan Emanuel, associate professor in Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment and a member of the Lumbee Tribe, which was hit hard by the 2016 and 2018 floods.

He added that these storms have exposed the risks associated with humans living near – and attempting to control – the water that dominates the Coastal Plain.

“We’re vulnerable because we’ve bought into the story that we can engineer our way out of flood vulnerabilities by building levees, ditching and draining landscapes,” he said. “You’re rolling the dice when you do that, and we know with climate change, you’re loading the dice unfairly for people who rely on that sort of infrastructure.”

Based on data from the 20th century, the amount of rainfall associated with Floyd was believed to be a 1-in-1,000 year event in some areas – better stated as having a 1 out of 1,000, or 0.1%, chance of happening in any given year. The two additional, and even wetter, storms since then have shown that these events are becoming much more common than we once believed.

“That can be confusing when we talk to the public; we just had that five years ago, so why is it happening again?” said Dr. Reide Corbett, the executive director of the Coastal Studies Institute and a contributor to the North Carolina Climate Science Report.

As rainfall statistics are recalculated with more recent data, he suggested so-called 100-year flood events could become more like 10-year events, or having a 10% chance of happening in any year. Given that chance of occurrence, we shouldn’t think about them as flukes, but rather the sorts of storms that will happen again in our lifetimes.

“We need to start planning now for this sort of change,” he said. “We’re going to have another Floyd, another Matthew.”

Impacts on Coastal Communities

Other consequences of climate change in eastern North Carolina include rising sea levels and saltwater intrusion that are threatening towns and residents across the Coastal Plain.

Corbett said salt is beginning to creep into drinking water supplies in Greenville – remarkable, given how far it is from the ocean and sounds.

And farmers are also fighting the inland push of increasingly salty water.

“It’s a huge concern,” said Rod Gurganus, the Beaufort County extension director. “It only affects a certain number of acres, but it takes those acres practically out of production.”

At the flattest, lowest-lying parts of the coast in Beaufort, Pamlico, Tyrrell, Hyde, and Dare counties, Gurganus said traditional crops may not be options in the future, and farmers have started exploring salt-tolerant crops such as asparagus, just to keep the land in use. But even that is a huge question mark as the water keeps rising.

“You do wonder how long some of these areas can remain in production before a rising sea overtakes them,” he said. “We’re hoping to find some solutions, but if that doesn’t happen, we’re going to have lots of land that’s good for nothing.”

The historical productivity and economic benefits of the Coastal Plain, including its easy access to rivers and ports, have had a significant impact on the landscape, which is also creating concerns for local communities.

“You can’t talk about adapting to climate change in isolation, because the Coastal Plain is simultaneously experiencing land use change,” said Emanuel.

That includes changes in agricultural practices, such as the rise in Confined Animal Feeding Operations, or CAFOs, which often feature large warehouse buildings with even larger waste footprints in the air and water. Within the bioenergy sector, mills processing wood pellets to export to global energy markets have also become more widespread.

Pollution from these facilities is happening in the vicinity of Tribal communities, and Emanuel worries that when combined with climate changes, it might become intolerable for them to live on their ancestral lands.

“If you have to leave and uproot who you are, then who are you?” he wondered.

One group assisting coastal communities under threat from these changes is the North Carolina Office of Recovery & Resiliency, or NCORR. It was established after hurricanes Matthew and Florence and is supported by federal and state funding from those disaster declarations.

Andrea Webster, the resilience policy advisor at NCORR, said the back-to-back nature of those two storms highlighted the challenges facing coastal communities.

“Climate change is a threat multiplier,” she said, “which makes it feel that much more overwhelming, and it’s hard to know how to tackle it.”

NCORR is now working in those hard-hit areas, supporting projects including infrastructure improvements and affordable housing to make sure towns are rebuilding smarter, safer, and more resilient than they were before.

“At the most basic levels, we want our communities and economies and ecosystems to meet their basic needs, before, during, and after a natural disaster,” said Webster.

That work by NCORR ranges from elevating homes being rebuilt through its Homeowner Recovery Program, to helping property owners flooded by Florence secure buyouts so that ideally, they won’t be underwater when the next storm strikes.

Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies

In the wake of those recent storms, people across the Coastal Plain have been forced to adapt to the new normal and take steps to mitigate against the extensive impacts of those sorts of events. At a state and local level, that has included rethinking and rebuilding our infrastructure to better weather our future climate.

Dr. Barbara Doll is an extension associate professor in NC State’s Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering. Her work includes modeling studies that help towns like Windsor, which has been repeatedly inundated since Floyd, assess the location and design of bridges and roads that might exacerbate or prevent flooding.

“These future scenarios don’t look great,” said Doll, who pointed to the planned changes to Interstate 95 in Lumberton, including widening it and replacing its bridges to span longer distances, as an example of the scope of work that may be necessary across other parts of the Coastal Plain.

She emphasized that changes far from the immediate coastline could help absorb some of the downstream impacts during hurricanes and other heavy rain events. For instance, we could convert marginal croplands into grasslands and forests, or add more wetlands to act as a buffer for floodwater storage.

Her computer modeling work also shows the benefits of moving away from levees to more distributed systems of water management so there’s no single point of catastrophic failure. Where that isn’t possible, she cautioned against locating energy systems and wastewater treatment plants in flood-prone areas.

“The most important use of a floodplain is to store water in those rare, extreme events,” said Doll.

In some wetland areas, changes are already being made to help those critical ecosystems – and the state – adapt for the future. In the Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge and the Dismal Swamp State Park, groups such as The Nature Conservancy, the US Fish & Wildlife Service, and the US Geological Survey are restoring pocosin wetlands that were historically ditched and drained.

“Wetlands are very good at sequestering carbon, so that’s one way they can help mitigate the effects of climate change,” said Dr. Marcelo Ardón, an associate professor in NC State’s Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources.

Since organic soils oxidize and release carbon dioxide when they’re exposed to the air, raising the water table helps them instead store this carbon underground and underwater. By quantifying the decreased carbon emissions, the groups doing this wetlands work are setting up the framework to create carbon credits that could be used to pay for additional restoration.

For farmers feeling the effects of not only storm-related flooding, but also sunny day flooding and rising water levels, they’re making changes to protect their homes and fields.

“Climate is going to drive a lot of this,” said Gurganus. “It’s already happening with saltwater intrusion in low-lying areas. Farmers are walling themselves off and installing pumps to pull water off the land.”

Increasing summer temperatures are also forcing farmers to consider what and when they’re planting, such as shifting to earlier-maturing corn varieties that can be harvested before the summer heat hits.

Of course, not all parts of the coast will be habitable in the future as sea levels rise and flooding becomes even more frequent. While a simple-sounding solution is for people to move away from areas prone to such problems, that ignores a key part of why the Coastal Plain is special in the first place.

“Planners, engineers, and policymakers often don’t understand that deep connection people have to their land and their local environment, and they often want those people to leave,” said Dr. Cindy Grace-McCaskey, an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at East Carolina University.

That’s been particularly true of Princeville, which withstood the flood from Floyd and rebuilt, but has patiently awaited updates to make the town more resilient. Upgrades to the town’s dike have been designed with funds appropriated, but not yet implemented after Matthew’s flooding caused an additional delay.

Meanwhile, the town has purchased two plots of land totaling 141 acres where they can relocate some of their most vulnerable commercial property, along with the fire department, town hall annex, and new housing, of which there is a shortage in eastern North Carolina.

For residents like Mayor Jones, the setbacks from flooding storms have only strengthened his desire to see the historic town founded by formerly enslaved people live on.

“We are nowhere near a breaking point,” he said.

“I always reflect back on our forefathers in 1865 when they built the town, and here we are in 2022 with all the technology we have at our disposal. There’s nothing that tells us we cannot protect the town of Princeville if we so desire.”

Support for Princeville’s new land acquisition came from a $12 million grant under FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, or BRIC, program. NCORR has helped other areas secure these grants, including the Outer Banks town of Duck, which is installing a living shoreline as a more natural way of managing water and preventing the routine flooding of Highway 12.

Webster said NCORR has also connected representatives from the nine multi-county regions aligned with Councils of Government in eastern North Carolina to combine their local knowledge and climate change expertise, identify vulnerabilities, and assess feasible, high-priority projects to better meet their needs.

This collaborative approach helps with one of the most common challenges Webster has seen in coastal communities, including in Elizabeth City during a visit this spring.

“They know how they’re struggling,” she said. “We just need to guide them toward a solution they can trust and that they feel is equitable, fair, and efficient.”

Essentially, NCORR hopes to act as a safety net that keeps vulnerable communities from failing, while also giving them the tools needed to succeed in becoming more resilient.

Making a More Resilient Coast

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the variability we find across the Coastal Plain – between rural and urban areas, located well inland or right at the coastline, with a diversity of residents from Indigenous people to recent transplants – there is no one-size-fits-all solution to preparing for the future.

“Resiliency takes on many forms,” said Doll, who reiterated the need to secure our floodplains through restoration efforts.

Among the potential solutions is a practice called water farming, in which landowners such as farmers enroll part of their property in exchange for an up-front, often 30-year payment. These lands are then used for wetland conversion, flood mitigation, and water storage.

Doll was part of a project that conducted a survey of landowners along Stoney Creek in Wayne County, and she said many were surprisingly open to the idea.

“If people feel they are fairly compensated for their loss of land, then they’re okay with trying out these types of practices,” she noted.

Grace-McCaskey said that sort of proactive thinking is needed, but she would also like to see it coupled with pragmatic policies that prevent rebuilding in areas that have seen repeated flooding.

“Fifty years from now, these places are going to be underwater,” she said.

In areas that do want to make a last-gasp effort to stay above water, Grace-McCaskey supports projects like the Lake Mattamuskeet watershed restoration plan, which includes support for water quality and waterfowl habitat restoration, along with the installation of a new pumping station and repairs to residential septic systems, which are among the most vulnerable infrastructure at the low-lying coast.

When assembling these community-level resilience plans, Corbett agreed they should include “hard conversations about areas that we shouldn’t rebuild.”

Even when properties are rebuilt, he added that more careful consideration should be given to future changes, such as expansion of the floodplain as storms get wetter and an additional foot or more of sea level rise along the coast.

That could include thinking about wastewater treatment, like using air-forced aerobic systems in areas where the water table is higher, or deciding how much beachfront homes should be elevated.

But one key lesson learned from Floyd – when we thought it truly was a once-in-a-lifetime event – is that building back the same as we’ve always done is not a sustainable strategy.

“We need to be honest about that vulnerability,” said Corbett.

Individual homeowners can take other actions to increase their resilience to our climate changes.

“Think about drainage on your own property and where that water is going,” added Corbett. “Can it be contained and not lost to your next-door neighbor?”

Webster encourages people to put any extra money into a household rainy day fund, given that our literal rainy days are getting wetter and even more impactful.

“Store some money away to be prepared for what’s going to happen in the future,” she said.

She also suggests checking with neighbors after storms hit and offering assistance if possible, since recovery and resilience is a true team effort.

“When you ask people across eastern North Carolina, ‘what is the strength of your community?’, they’ll say our neighborhoods, our people.”

That community-centric approach is a key facet of North Carolina’s Indigenous communities. From Emanuel’s experiences as a member of the Lumbee Tribe and as an environmental scientist studying our cultural history relative to the water, he noted a few steps people can take in the face of natural disasters.

Canning food, rather than freezing it, can make your emergency supply more resilient. And when the power goes out, he suggested using churches, schools, and community centers as gathering places, equipped with solar- or wind-powered systems and ideally energy storage capabilities so they’re not reliant on the same storm-shocked grid.

While this would require up-front costs now, Emanuel said that planning well and investing appropriately could ultimately help us stay safe and connected during future disasters.

In terms of finances, for those rebuilding after storms, grants and other support are sometimes available, and NCORR can help identify those opportunities.

Emanuel also encouraged us as a society to change how we think about our Coastal Plain. In some ways, this is the easiest change since it costs nothing. But it’s also perhaps the most difficult since it makes us rethink our approach to manipulating – rather than coexisting with – the land and water.

“The main theme from the last 200 years of history in the Coastal Plain has been doing things to the land itself that affect how water flows or drains to make the land more valuable or more productive,” said Emanuel.

That started with schemes In the 1800s to widen and clear rivers to access forests for logging, and has continued with the CAFOs and pellet mills stamped across the landscape in the past 30 to 40 years.

Given the environmental impacts that recent storms have exposed with those developments, and the near-certainty that our future climate will bring more storms, more flooding, and more variability, Emanuel imagines a new philosophy about the Coastal Plain.

“I hope that instead of having the mentality of ‘how can we make water do what we want to extract more value in the land?’, we consider what would it look like to truly appreciate that this is a place that is ruled by water, that water has always dominated, and use that for the collective good.”