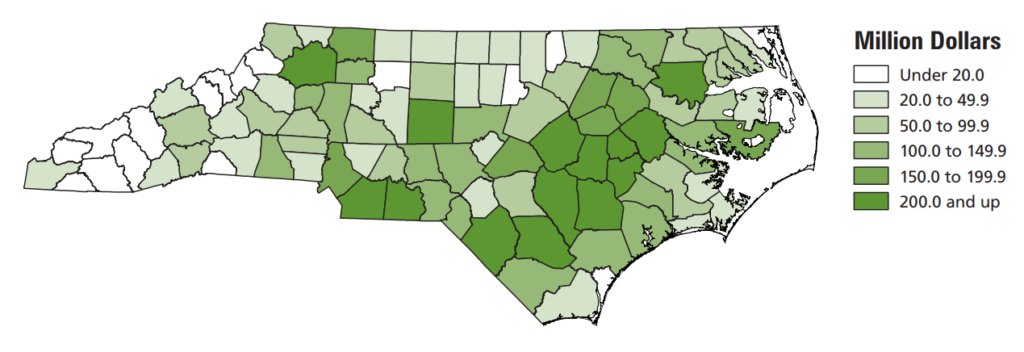

Drive or fly across the Coastal Plain and you’re sure to find farms of all forms. Many grow cash crops such as cotton, tobacco, and corn. Some raise animals, including livestock and poultry. And others specialize in aquaculture, like clams and oysters.

Altogether, agriculture accounted for more than $10 billion in statewide revenue in 2020, or 6.1% of North Carolina’s gross domestic product. Even as industries such as manufacturing and banking have emerged as our economic leaders in the 21st century, agriculture remains a staple, especially in the Coastal Plain.

There are good reasons why farms have thrived in eastern North Carolina – which, according to 2017 data from the Office of State Budget and Management, includes 2.9 million acres used for harvested cropland, or 21% of the total land area.

To discover why, we need to dig in – literally – to the soils of the Coastal Plain as this blog post series about the region continues.

Emerging from the Sea

Geologically speaking, growing anything besides seaweed in eastern North Carolina is a relatively modern development. As mentioned in our first post, the bedrock of eastern North Carolina was once an ocean floor.

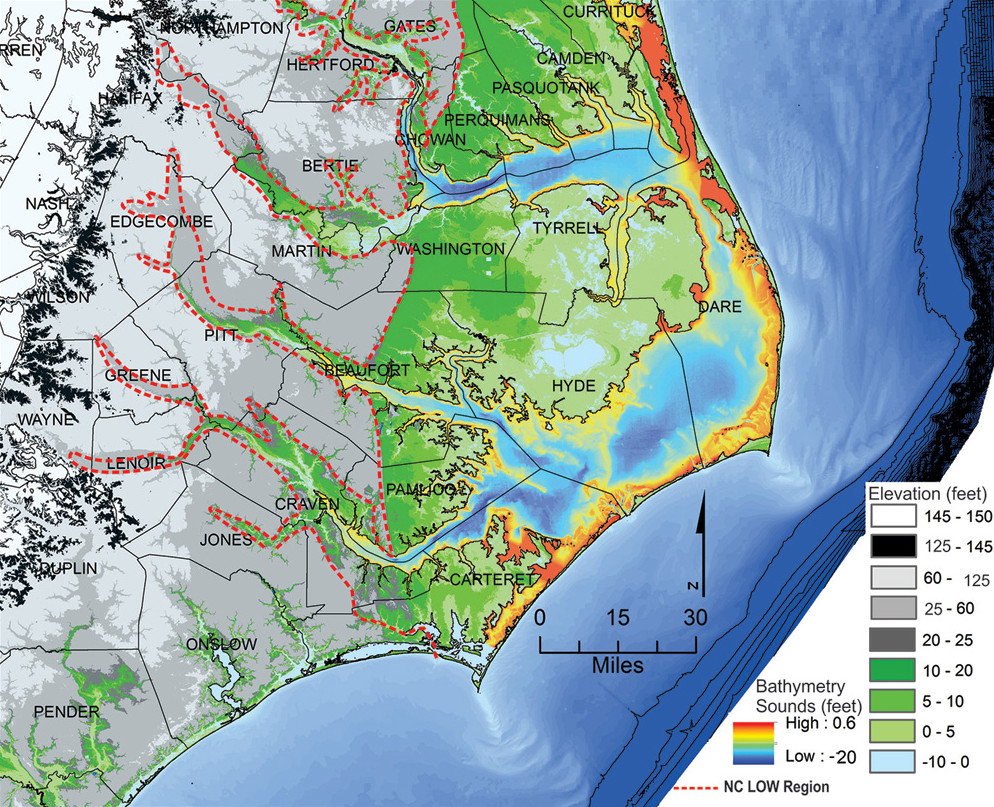

According to Dr. Shannon Klotsko, assistant professor of geology at UNC Wilmington, the greatest inland extent of that ocean – and the boundary of the oldest terrain continuously above water – is called the Orangeburg Scarp, which runs through present-day Scotland and Hoke counties.

That sea level maximum happened roughly three million years ago during the mid-Pliocene Warm Period. Since then, inland areas in the Coastal Plain have cyclically been covered by water, then above it, “going back and forth between being exposed and not being exposed,” Klotsko said.

While three million years seems like a long time, it’s incredibly short compared to, for instance, the history of the Appalachian Mountains, which began forming almost 270 million years ago.

Klotsko said far-eastern areas such as the Albemarle-Pamlico peninsula have consistently been above water for only about 125,000 years. That corresponds to the end of the last interglacial period, when sea levels were 20 to 25 feet higher than today.

The boundary of this slightly less ancient shoreline is known as the Suffolk Scarp, and it’s where our state’s geological history intersects with our modern agricultural experiences.

Origins of Our Coastal Soils

Rod Gurganus is the Beaufort County extension director, and he can still see the effects of this scarp in his neck of the woods.

Like the Orangeburg Scarp, which coincides with the fall line and the western boundary of the Coastal Plain, the Suffolk Scarp is a step-up in elevation. Parts of Beaufort County east of the Suffolk Scarp sit just 2 to 5 feet above sea level, while in the west, the elevation rises to nearly 60 feet just south of the Pamlico River near Chocowinity.

In the east, Gurganus said, soils are like wetlands, with lots of organic content, often from decomposed trees. West of the scarp, the soils are more mineral-rich, with lots of sand that improves drainage.

But how did those different types of soils get there in the first place? After all, when we plant in eastern North Carolina, we’re not digging into that prehistoric seafloor, but rather into many feet of softer material laying on top of it.

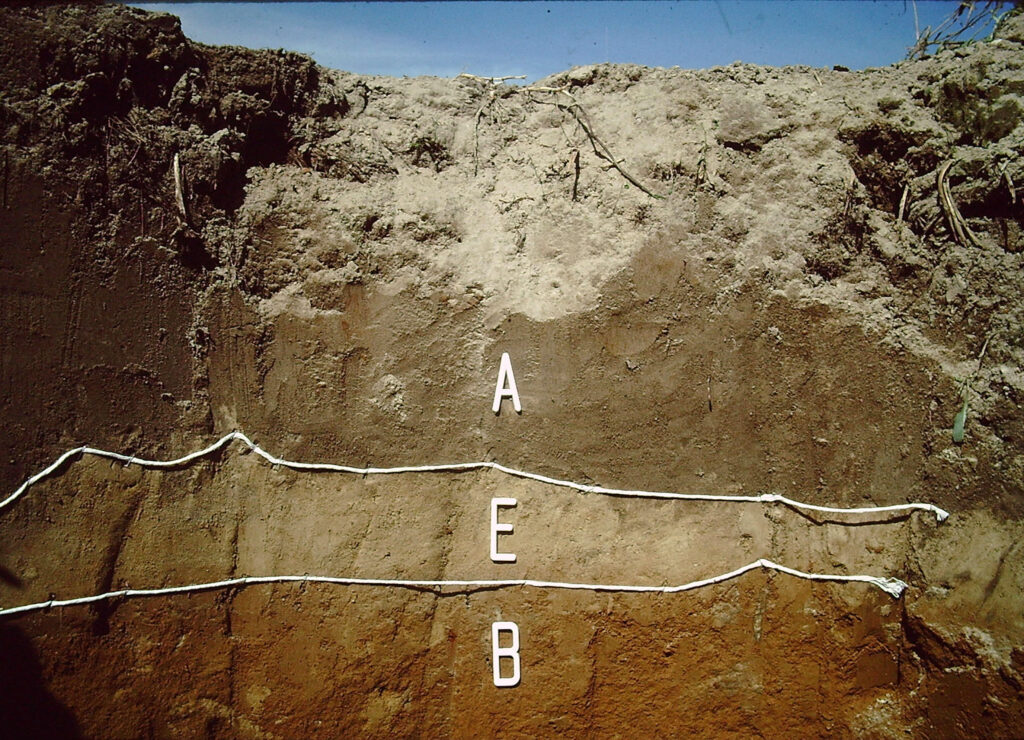

Dr. Mike Benedetti, a professor of geography at UNC Wilmington, said the soils of eastern North Carolina came from sediments that were eroded off the Mountains, Blue Ridge, and Piedmont, and then deposited in shallow marine environments after rivers carried them down to that ancient ocean.

“The soils we see today formed under forest cover and a warm, humid climate since the end of the last glacial stage,” said Benedetti. “Soils in the inner Coastal Plain are fairly deep and intensely weathered, having developed through multiple glacial cycles, while soils in the outer Coastal Plain are more recent and weakly developed.”

That’s a sharp contrast in both the origins and the composition of the soils found across the Mountains and Piedmont, Benedetti said, “where the soils formed from weathered bedrock, leading to more rock fragments and clay-rich soil.”

Curiously, despite the history of the Coastal Plain as an ancient seafloor and its proximity to water even in modern times, you’re not likely to find much marine evidence, such as fossils or shells, within the soils.

That’s partially because of the nature of coastal soils as eroded, weathered material that originated from non-marine areas. Decomposing organic material also makes soils in this region more acidic, which tends to dissolve bone or fossil fragments.

The main exceptions are right along the beaches – where the shells or shark’s teeth you find are almost certainly more recent – and in some quarries near Wilmington, where ancient marine fossils were better preserved in limestone deposits.

Soil Specialties for Agriculture

The makeup of our coastal soils has made them useful for farming – a fact known for thousands of years by Indigenous people living on the land.

Tribes in eastern North Carolina grew corn, beans, gourds, and tobacco, among other crops. While their land management – such as not plowing the fields – was chided by European settlers, English writer Thomas Harriot noted that the fertile soil of the region hardly needed that level of attention to be productive.

Farming practices have obviously changed over time, particularly with the advent of machinery to assist with all stages of preparation, planting, and harvesting, but the same core crops are still grown across the Coastal Plain.

The nature of the soils there makes them uniquely suited to certain crops. North Carolina leads the nation in tobacco production, and the well-drained soils of the western Coastal Plain make it a sweet spot for the flue-cured variety.

The northern Coastal Plain, especially west of the Suffolk Scarp, is ideal for cotton and peanuts. In the south, we grow more corn and sweet potatoes – and North Carolina produced 77.2% of the nation’s sweet potatoes in 2020, according to USDA/NASS.

Heading eastward across the Suffolk Scarp, we transition from sandy forest soils – classified as ultisols and spodosols – to wetland soils, also known as histosols. While these aren’t ideal for most of our traditional cash crops, they can still be farmed with a bit of care.

Within these eastern organic-rich soils, we can grow corn, soybeans, and vegetable crops like potatoes. These soils even offer some advantages, particularly during those summer stretches when rain showers seem to stay away.

“They give us a few more days of stress-free growing, compared to a sandier soil,” said Gurganus, noting that a shallow layer of organic matter in the rooting depth can help these soils hold onto moisture, which ultimately benefits crops.

In the recent past, these lands with highly organic soils were believed to be promising for agriculture, so they were cleared for farming and even mined to extract methane from their peat content as an energy source.

But that excess organic content can be “too much of a good thing,” Gurganus said, along with the lack of sand or silt for drainage. Some plots have been ditched and drained for agricultural purposes, but in these low-lying eastern areas, consistently growing crops is challenging because of the water, water everywhere.

“That close to sea level, a high water table and rising sea levels make it more difficult,” he said.

“In our area, you’re never more than 300 feet from a ditch or a canal. Practically everything is wetlands, and if those ditches and canals are stopped up or filled in, we’re going back to wetlands.”

With so much concern about the water, it’s no surprise that farmers are constantly watching both the soils below and the skies above to see where the moisture is coming from, and where it’s going.

Climate Challenges for Crops

North Carolina’s geographical location, nestled between two large bodies of water – the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico – gives us a moist and humid climate with roughly even seasonal precipitation all year round.

We’re also relatively far south and shielded from continental cold air masses by the Appalachians, which gives us a long growing season that lasts nearly eight months in southeastern parts of the state.

That makes our climate appropriate for agriculture, although that doesn’t mean growing crops is easy, and it’s definitely not getting any easier. For one, much of our rainfall in the late summer and fall comes from tropical systems.

“We get our share,” said Gurganus. “Hurricanes are a big deal for us, especially in September and October in the harvest season.”

The heavy rain from these storms can cause crop quality issues such as mold, while high winds can blow down even well-developed and deeply rooted crops.

Farmers sometimes stagger planting dates so that when a big storm threatens, they can harvest some before it hits and avoid leaving the rest of the crop in water-logged fields for too long afterwards.

Droughts can also be an issue, and during our most severe and longest-lasting events such as the 2007-09 drought, the agriculture industry in North Carolina suffered losses totaling hundreds of millions of dollars.

Some farmers have invested in irrigation to better weather these dry times, but its usage is not widespread, and money is often better spent in other ways – particularly for managing the opposite end of the moisture spectrum.

“Too much water is usually our greatest limiting factor,” said Gurganus, who noted that some growers are installing tile drainage systems, which remove excess water after heavy rain events. The addition of underground woodchip bioreactors can also filter nitrogen from agricultural runoff and improve the water quality in streams near farm fields.

Further complicating agricultural matters are the climate change-fueled extreme events we’re seeing.

“Every farmer will look at their records over time, and they all acknowledge that something is changing,” said Gurganus. “We’re seeing more intense rainfall, more intense storms, the growing season is getting longer, the last frost is getting earlier over time.”

For many farmers, the first sign of trouble was the flooding from Hurricane Floyd in 1999, the scope of which was repeated after Matthew in 2016 and Florence in 2018. All three dropped extreme rainfall totals never before seen in a single storm, and left much of the Coastal Plain and its millions of harvested acres suddenly vulnerable.

In response, Gurganus said some farmers began improving drainage infrastructure that was unmanaged for years, although this infrastructure can still be overwhelmed, “getting more water quicker than ever before” during these storms.

Other farmers have reshaped their land, adding a crown in their fields to better shed standing water away from crops and into ditches.

And in a few places, such as low-lying Hyde County, repeated flooding and saltwater intrusion have created concerns that current farmland may not be arable in the near future.

Gurganus points to his own proverbial backyard in Beaufort County, which straddles the Pamlico River, mostly right at sea level east of the Suffolk Scarp. While it has historically ranked among the top corn-producing counties in the state, he said many of the flood-prone farms along the river are now being sold off to make way for residential housing.

A changing climate may also affect the viability of certain crops. Compared to the Corn Belt in the Midwest, our summer nights are warmer in North Carolina, which limits corn yields by shortening the grain fill period and reducing respiration rates.

The North Carolina Climate Science Report noted that summer average temperatures have reached record levels in recent years, including our state’s top three hottest summers in 2010, 2011, and 2016.

Projections show this summertime warming trend is likely to continue, which could make some of the crops we’ve grown in North Carolina for hundreds of years less productive or outright unviable in the future.

While genetic advancements like hybrids of soybeans and corn could build some resilience against these changes, such as adding more tolerance to excess moisture, salinity, and pest pressures, there are no magic beans that farmers can plant to fully weather our emerging climate challenges.

If there were, then you can bet some enterprising farmer throughout the history of our Coastal Plain would have found them, planted them, and sold them by now.