In all its forms, precipitation piled up in a wet January, although drought remains in some areas. Cool weather also reversed our warm December pattern – but how long will it stick around?

Frozen Precipitation Fuels a Wet Month

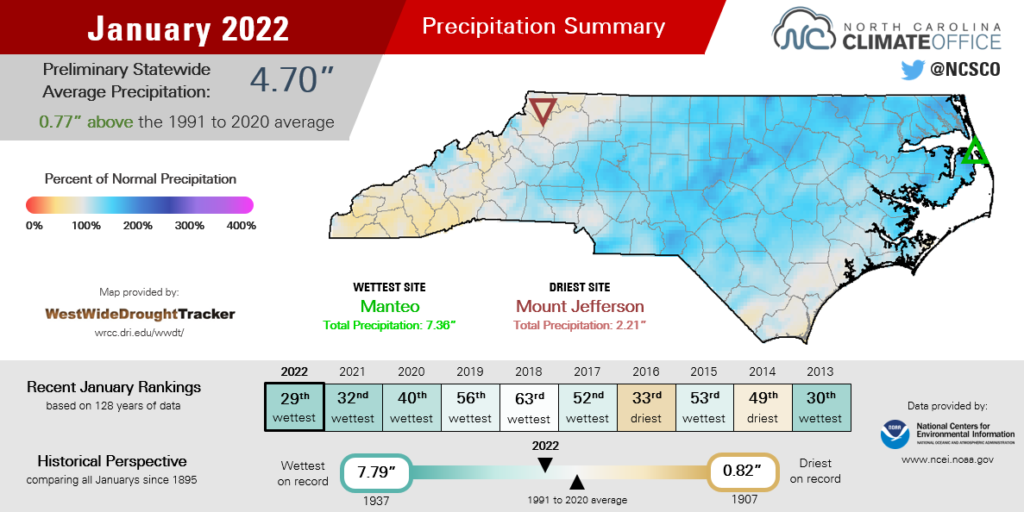

The skies opened up and brought a variety of precipitation types, which added up to make for an overall wet month. The National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) reports a preliminary statewide average precipitation of 4.70 inches and our 29th-wettest January since 1895.

The eastern Piedmont was one of the wettest areas after that mixed bag – from rain on January 3 to sleet on January 16 to snow on January 21. Chapel Hill had 6.26 inches of precipitation and its 11th-wettest January out of the past 122 years, while Raleigh received 5.97 inches to tie for its 13th-wettest January on record.

Farther east, Roanoke Rapids had 6.64 inches, or 2.98 inches above normal, and its 2nd-wettest January since 1962. At Hatteras, the 7.10 inches made for the 14th-wettest January on record there.

It was also a notably snowy month for much of the state. Edenton had 5.2 inches – mostly during the January 21 storm that brought the highest totals in the northeast – which was the most snow in a single month there since January 2018. In Charlotte, the 4.3 inches of snow was the most since 8.4 inches in February 2014.

Greensboro measured snow during each of our four weekend events, finishing the month with 1.8 inches on January 29. Those four snows in a four-week period are the first time it has snowed with such frequency in the Triad since January 2000. Their monthly total snowfall of 8.2 inches also exceeds the annual average of 7.1 inches.

However, not all areas got in on the snow – or the wet weather in general. Wilmington saw only a few flakes along with a glaze of ice on January 21, and the monthly total precipitation of 4.14 inches was only 0.3 inches above normal.

While parts of the Mountains enjoyed snowy scenes on January 3 and 16, the offshore storms later in the month mostly missed western North Carolina, and they finished the month with below-normal precipitation.

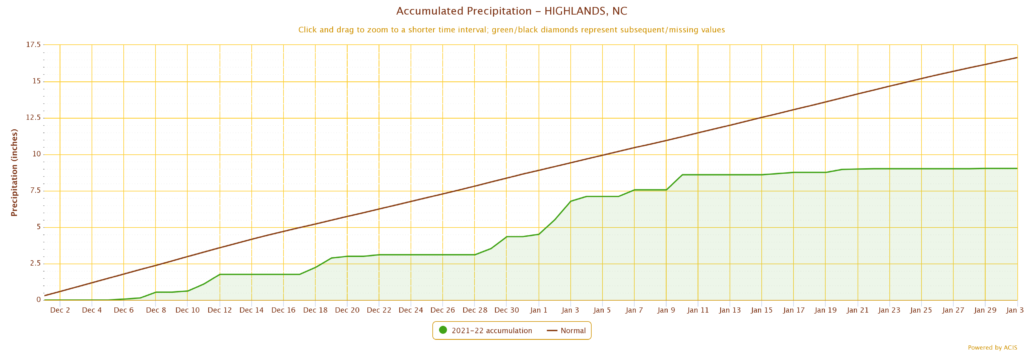

Pisgah Forest had its 21st-driest January since 1940 and was 2.4 inches below its normal monthly precipitation. In southern Macon County, Highlands – climatologically one of our wettest spots, averaging more than 88 inches per year – started 2022 on a dry note, with 4.68 inches and its 31st-driest January on record.

That continued a dry winter so far, with Highlands seeing only around half of its normal precipitation since December 1 – 9.03 inches compared to a typical December and January total of 16.64 inches.

Despite the Snow, Some Drought Lingers

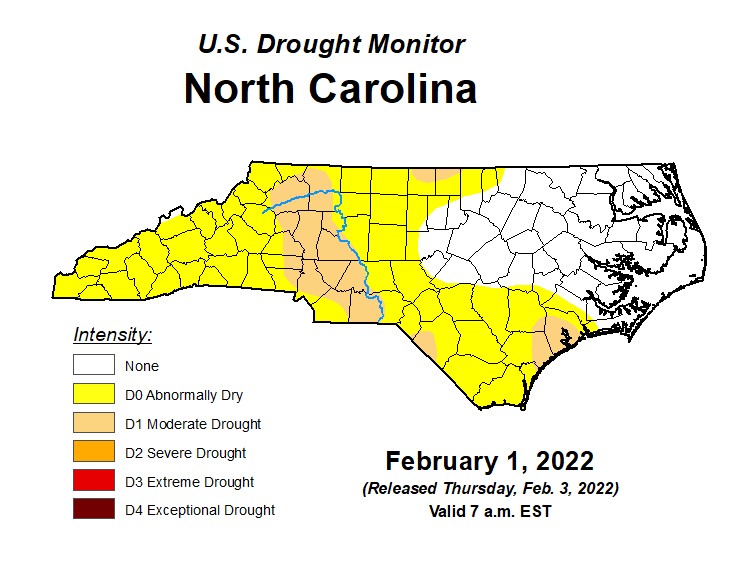

After three consecutive dry months in October, November, and December, our January precipitation helped reverse the spread of drought across much of the state. However, one wet month has not been enough to fully eliminate all signs of dryness.

While your backyard has probably been wet and brooks have been babbling after the recent infusion of moisture, drought and its impacts are not only skin deep.

The ground may be saturated, but deeper soils are still dry across the northern and western Piedmont and in the Sandhills — the same areas where Moderate Drought (D1) is present on the US Drought Monitor.

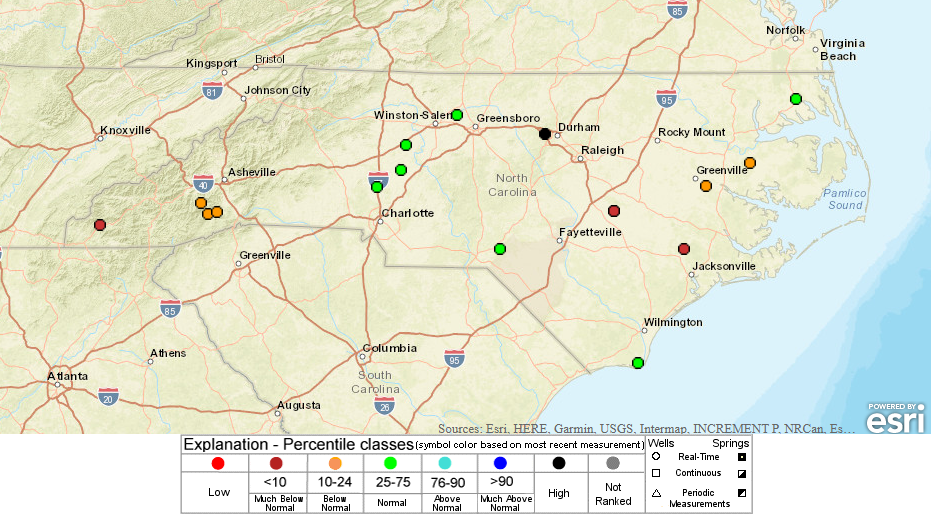

Groundwater levels also take longer to respond to rainfall and often require a prolonged period of precipitation to fully recover from seasonal shortfalls like we had late last year. Even after a wet January, wells across the central Coastal Plain continue to show below-normal levels for this time of year. In the west, groundwater levels have declined further after another dry month.

Streams in the Mountains and Foothills received brief boosts from snow melt, but many gauges finished the month below their normal levels. That includes the South Toe River near Celo and the French Broad River at Blantyre, which were both below their historical 10th percentile for the month of January.

Even some of the snowy spots in January didn’t pick up enough precipitation to overcome their deficits from the fall. While Charlotte was 0.7 inches wetter than normal in January, it remains 3.1 inches below normal since November 1.

Many western sites have even greater three-month deficits, including 8.0 inches below normal in Boone, 8.1 inches below normal in North Wilkesboro, and 12.0 inches below normal in Brevard.

All in all, it’s a good reminder that drought impacts can be tougher to spot in the wintertime, but a few weeks of warm or dry weather could quickly drive these impacts back to the surface — whether they’re moisture-sapped soils, newly sprouted plants that are slow to grow, creeks creeping down to a trickle, or increasing fire danger.

A Wintry Chill Arrives

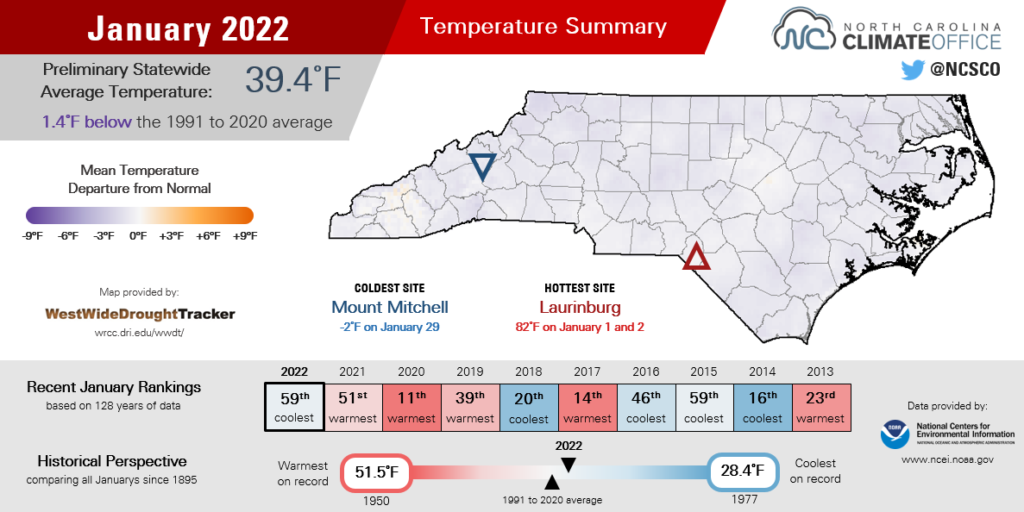

The past month felt far from spring-like thanks to our frozen precipitation and cooler temperatures. NCEI notes a preliminary statewide average temperature of 39.4°F, which was tied for our 59th-coolest January in the past 128 years, and 1.4°F cooler than the 1991 to 2020 average.

After being winter-hardened in recent weeks, it’s easy to forget that we started the month in a warm pattern that left flowers blooming and grass greening up well out of season.

The frontal passage on January 3 ushered in a much colder air mass, and also signaled a pattern change that stuck with us for most of the month, as a series of Canadian high pressure systems snuck in from the northwest.

Waynesville tied for its 21st-coldest January since 1895, while it was the 24th-coldest in Asheboro dating back to 1927. Tarboro tied for its 19th-coldest January since 1893. In most areas, it was the coolest January since another snowy month in January 2018.

With a warm December and a cool January now in the books, February is set to be the tie-breaking month this winter. At the moment, the odds favor warmer weather on the way.

For one, four of the last five Februarys have been warmer than normal in North Carolina, and each February from 2017 through 2020 ranked in the top 11 warmest on record. These Februarys were classic cases of a “false spring” — a few weeks of warm weather that encouraged farmers and gardeners to plant early, followed by below-freezing temperatures in March and April that halted the late-winter productivity.

La Niña events like we’re in now also favor warm Februarys, even during winters with a cooler interlude. That snowy January in 2018 was followed by one of our warmest Februarys on record.

Likewise, January 2000 – notable for those back-to-back-to-back-to-back snows in the Triad and the “Carolina Crusher” storm in the Triangle – was followed by our 26th-warmest February that saw the expansion of drought in the Mountains.

Current forecasts give North Carolina and much of the eastern seaboard at least a 50% chance of above-normal temperatures this month, spurred on by the ongoing La Niña pattern and a developing jet stream ridge off our east coast.

That’s no guarantee we’re done with cold or snow for this winter, but the freezer door at least appears to be cracking open with a thaw underway after our cool, snowy January.