It was the driest November in a lifetime, with rainfall in retreat whether we were warm or cool. Drought has expanded and intensified after our warm, dry fall.

Dry Weather Dominates

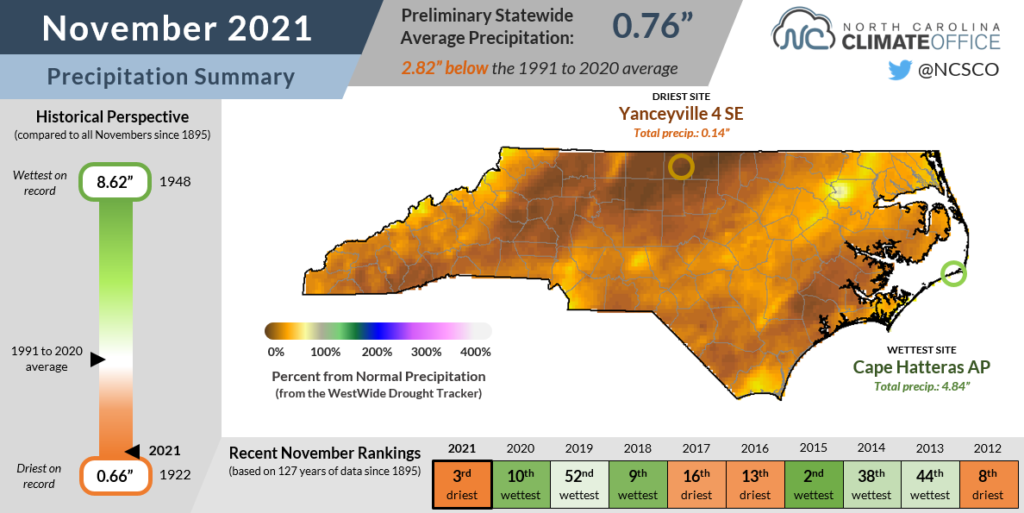

Like an overcooked turkey in the oven, November turned out extremely dry across North Carolina. According to the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), the preliminary statewide average precipitation of only 0.76 inches ranked as our 3rd-driest November since 1895.

To find another November this dry in North Carolina, we have to go back 90 years to 1931, which fared marginally worse with 0.75 inches of rain statewide, on average. That was part of an extremely dry fall across the southern tier of the US that corresponded with the onset of the Dust Bowl in the southern Plains.

Most of the state totaled less than an inch of rain last month, and some sites particularly in the northern and western Piedmont had barely enough rain to dampen the dust.

In Caswell County, Yanceyville received only 0.14 inches, which is the 2nd-driest month in that station’s 24-year reporting history, after September 2019. Next door in Rockingham County, Eden reported 0.20 inches for its 2nd-driest November since 1950.

Greensboro measured just 0.30 inches last month, making it the 3rd-driest November there since 1903, and Hickory had its driest November out of the past 71 years with 0.35 inches of total precipitation.

One of the lone wet spots in the state last month was Cape Hatteras, which measured 4.84 inches of rain total, mostly from offshore moisture ahead of a cold front on November 12. While that was only 0.06 inches more than the monthly normal precipitation, they still fared better than the rest of the state.

Although November is climatologically one of our drier months, most areas were 2 to 3 inches below normal last month. That helped increase our seasonal precipitation deficits and push more of the state into drought.

Warm Days Mixed with Cool Nights

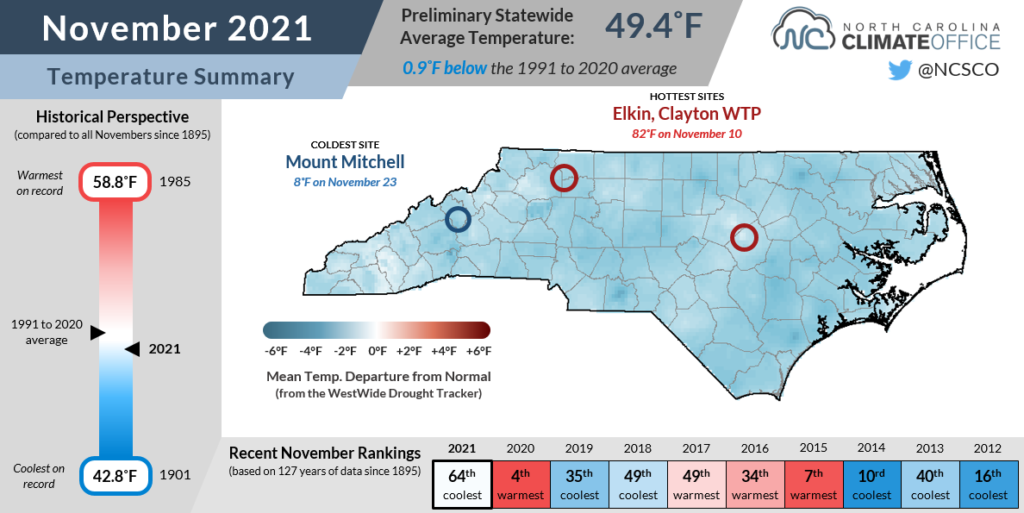

November brought our first sustained feel of fall, although those cooler days were balanced out by some warmer ones mid-month. As a result, it was our 64th-coolest November in the past 127 years, with NCEI’s data showing a preliminary statewide average temperature of 49.4°F, or 0.9°F below the recent 30-year average.

Our first cool-down came on November 4 and 5, as most sites across the northern and western Piedmont recorded their first freeze of the season.

The week after that saw a steady warm-up as high pressure built over the Southeast US — the same pattern that steered away most would-be rainmakers.

During that stretch, temperatures hit some impressive levels across the Foothills. On November 10, Elkin topped out at 82°F, making this only the third November in the past decade in which that Surry County town has had 80-degree temperatures.

Cool weather soon returned, as a dry cold front moved through on November 13, bringing freezing temperatures across the southern and eastern Piedmont the following morning.

Just two days later on November 16, temperatures dropped below freezing in most of the Coastal Plain, ending the growing season there about a week later than the historical average first freeze date.

The month wrapped up with mostly seasonable temperatures but also the return of high pressure across the region, which prolonged our dry pattern and worsened drought conditions.

Drought Develops in a Dry Fall

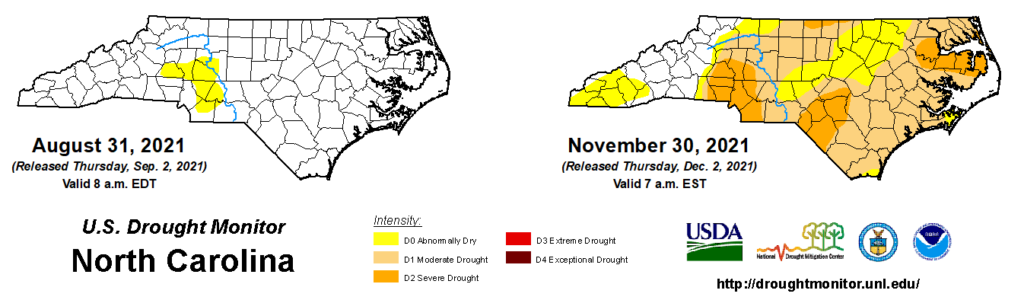

As of November 30, climatological fall is complete, and winter is upon us — although it won’t feel like it this weekend. The seasonal statistics confirm what you probably felt over the past three months: we started warm and were quite dry from September through November.

Preliminary data from NCEI shows a seasonal average temperature of 61.5°F, a degree warmer than the 1991-2020 average and our 21st-warmest fall on record. The statewide average precipitation of 6.88 inches was just 55% of the 30-year average. That ranks as our 16th-driest fall since 1895, and the driest since 2001.

The persistent lack of rainfall over the past few months, punctuated by our extremely dry November, has seen drought increase its grip on North Carolina. On the latest US Drought Monitor map, released this morning, 64.8% of the state is classified in drought, and Severe Drought (D2) has emerged across parts of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain this week.

The last time Severe Drought was in place at this time of year was in 2016, although at that point, the drought in the southern Mountains was beginning to improve with the onset of December rainfall.

This year, it appears our drought is only just beginning, particularly entering a La Niña winter that so far is making good on its promise of warmer and drier weather.

Here’s a regional rundown of current conditions across the state:

- The Mountains have mostly avoided any dry-weather impacts this fall thanks to heavy rain from Tropical Storm Fred in August and another soaking system in early October. However, some areas are beginning to see streamflows fall below normal, which helped Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions emerge across our westernmost half-dozen counties this week.

- The northwest Piedmont including the Triad has now entered Moderate Drought (D1), escalated primarily by short-term dryness in the past month. During that time, two large wildfires ignited, including the ongoing Grindstone fire on Pilot Mountain that has now burned 1,050 acres. Along the Virginia border, parts of northern Caswell, Person, and Granville counties degraded to Severe Drought this week.

- Severe Drought has also emerged in the western Piedmont including Charlotte, which has been dry since the late spring and early summer. Locally, it ranked as the 3rd-driest fall in Gastonia dating back to 1931 with only 3.04 inches of seasonal rainfall there.

- The Sandhills and parts of the southern Coastal Plain have also been dry since the early summer. Severe Drought now encompasses Lumberton and Fayetteville as streamflows have fallen below their historical 10th percentile for this time of year, and soils are dry several feet deep.

- The central Coastal Plain including the Albemarle peninsula has also seen the emergence of Severe Drought as part of a drastic seasonal turnaround. And after its wettest summer on record, Greenville recorded its 5th-driest fall with 3.82 inches of precipitation. Groundwater wells in Pitt and Jones counties have also fallen below the 10th percentile, while the Grantham well in Wayne County has hit its record low value for this time of year based on data since 1980.

Despite the declining streamflows, which represent critical inflows for reservoirs, most lakes across the state are in slightly better shape thanks to the season. Lower demands for irrigation and reduced evaporation should help reservoirs hang on to their water supplies this winter.

However, with little immediate rainfall relief in sight, some local water systems and municipalities could soon begin to implement either voluntary or mandatory conservation measures.

This may feel like déjà vu since we warned about similar impending impacts after the emergence of Severe Drought back in May. That was followed by a wet June in drought-affected areas that washed away any summertime drought.

With hopes that we’re applying an equal jinx this time around, it appears the drought we feared is finally here, only six months later than expected.