The past month included wet, windy weather along with warm temperatures and higher dew points that helped fog bedevil our October dawns.

Dark and Stormy Nights (and Days)

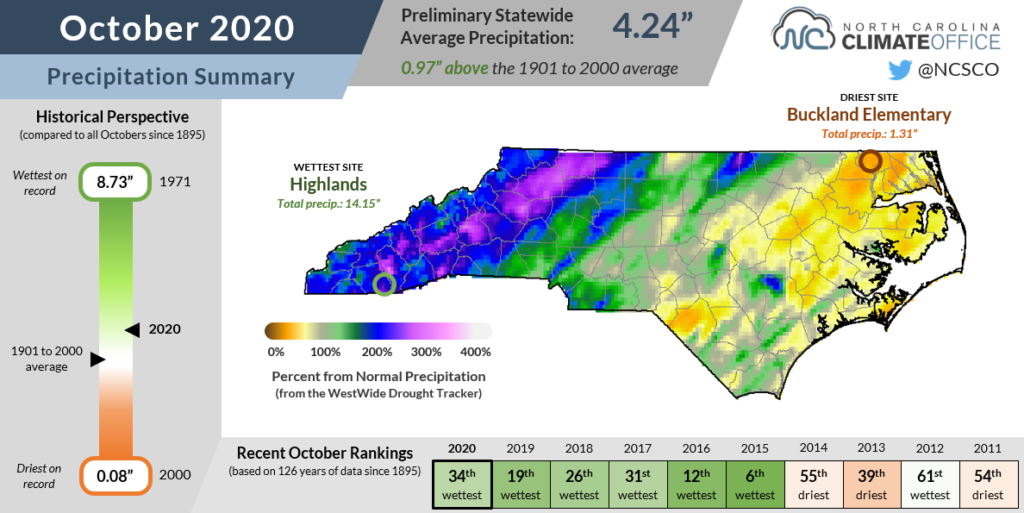

Multiple rainfall events including the remnants of two hurricanes drenched western North Carolina as part of an overall wet month. The National Centers for Environmental Information reports a preliminary statewide average precipitation of 4.24 inches and our 34th-wettest October out of the past 126 years.

In mid-October, Hurricane Delta hit the Louisiana coast and its remnants reached North Carolina, bringing at least 4 inches of rain in parts of the Mountains and more than 2 inches across the northern Piedmont.

Two weeks later on October 28, the remnants of Hurricane Zeta raced inland and remained at tropical storm strength even over the Mountains. Even with a fast forward speed, Zeta still dropped up to 5 inches of rain across western North Carolina in a 24-hour span.

Zeta also whipped up winds statewide, with gusts of more than 50 mph in the Triad and Charlotte areas. Duke Energy reported more than 500,000 power outages across the Carolinas during the storm.

It wasn’t just tropical systems contributing to a wet month. A cold frontal passage on October 24 and 25 brought statewide rainfall, including 2 inches across the central coast. Another front following shortly behind Zeta produced a line of thunderstorms across the Piedmont.

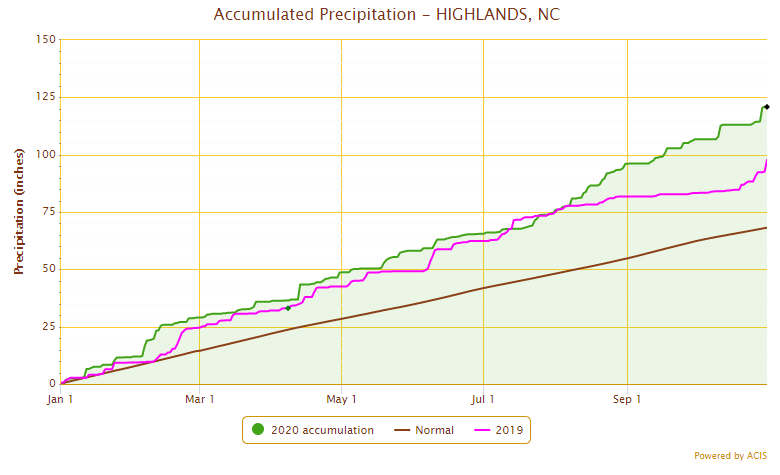

The result of those rain events was one of the wettest Octobers on record in parts of the Mountains. With 10.67 inches, Wilkesboro recorded its 2nd-wettest October since 1965, while Cullowhee had 7.70 inches and its 3rd-wettest October out of the past 110 years. Highlands had its 5th-wettest October spanning back 115 years, with 14.15 inches boosting its annual total precipitation to 120.87 inches.

Highlands is on pace for its wettest year on record, currently more than 23 inches ahead of last year’s total through the end of October. That site averages about 8 inches of rain in both November and December, so two slightly above-normal months to end the year could also make it a contender for the wettest calendar year at any station, currently held by the 139.94 inches in 2018 at Mount Mitchell.

The Coastal Plain generally didn’t see such heavy rain in October since those weather systems approaching from the west dried out as they moved eastward. Particularly along the Outer Banks, rain was limited last month, and Hatteras received only about half of its normal October precipitation, with 2.76 inches.

Despite that dry month at the coast, soil moisture and streamflow levels remain at or above normal. That’s partially because of rainfall in the late summer and early fall that has much of the coast 2 to 4 inches above their normal precipitation over the past three months.

Only a handful of sites such as Williamston, Ocracoke, and Laurinburg are in a precipitation deficit since the beginning of August, and the entire state has remained clear of any abnormal dryness or drought since Hurricane Isaias soaked eastern North Carolina in early August.

Warm Weather with Few Freeze Events

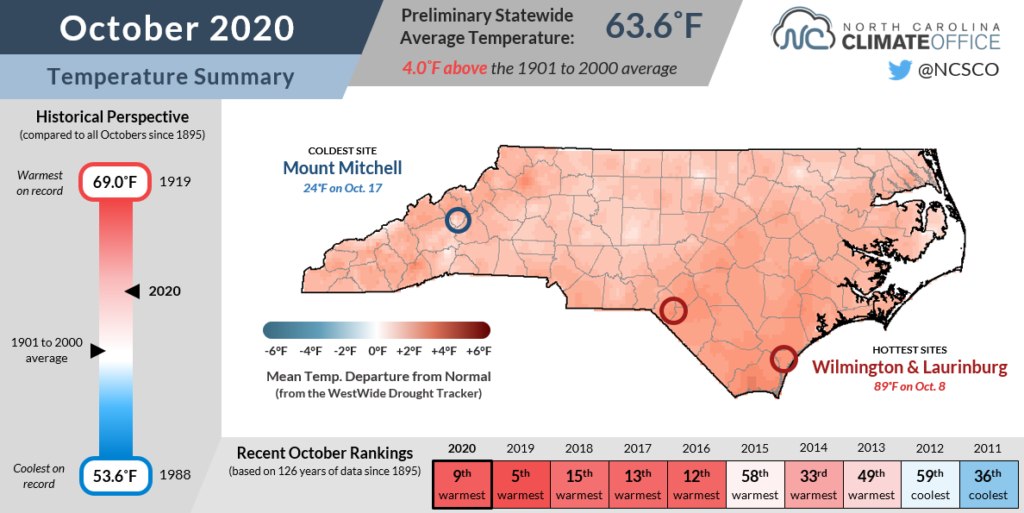

Even though we had several cold frontal passages in October, it wasn’t a particularly cold month. NCEI notes the statewide average temperature of 63.6°F ranked as our 9th-warmest October since 1895.

The prevailing upper-level pattern saw jet stream ridging over the US east coast, which invited a feed of warmer air from the south that boosted our temperatures.

For the eighth October in a row, our statewide average temperature was above normal. Locally, it ranked as tied for the 4th-warmest October in Elizabeth City since 1934 and the 5th-warmest in Banner Elk out of the past 107 years.

Elevated by high dew points — more on that below — our nighttime low temperatures were also particularly warm. Our average minimum temperature of 52.8°F was 5.5°F above normal, and it ranked as our 11th-warmest October based on that average minimum.

While parts of the western Piedmont and Foothills often expect their first freeze by the end of October, it was delayed until early November this year. At sites like Morganton, where the average first freeze occurs on October 21, and Hickory, with an average first freeze date of October 31, this October was freeze-free as lows never dropped below the upper 30s.

Even Asheville, which has an average first freeze date of October 17, didn’t see its first sub-freezing temperatures of the season until November 2. As sites across the state fall below freezing over the next month or so, the growing season will officially come to an end.

Fog Blankets the State

Fitting of the run-up to Halloween, a fearful fog formed last month on a number of mornings — our darkest of the year before the end of Daylight Saving Time brightened our days a bit earlier.

Throughout the month, dense fog advisories were in place across the southern Mountains and the central and eastern Piedmont, and the statistics show just how foggy the month was in those areas.

The Raleigh-Durham Airport reported 34 hours with fog last month — the most since December 2015, which had 42 foggy hours, and tied for the 11th-most of any month since 1997. In Asheville, the 28 hours with fog in October is the most since August 2018.

Climatologically, our foggiest months are in the late fall through the winter, so foggy October mornings are not particularly unusual, but they did occur more often in some areas last month.

To understand why, consider how fog forms. When the air temperature reaches the dew point, the air becomes saturated and tiny liquid droplets condense out. Because they’re so small, they don’t fall like raindrops, but remain suspended in the air, essentially forming a cloud near the ground level that can reduce visibility and create hazardous travel conditions, especially in the dark morning hours.

Saturation can occur either as temperatures fall to the dew point or as air moistens and the dew point rises to meet the temperature. The first of those effects, known as “radiation fog”, is most common during this time of the year as clear skies and lengthening fall nights help temperatures drop a bit further.

That was even more common this October thanks to an airmass rich with Atlantic and Gulf moisture. On some mornings, dew points were in the low 60s, even in the Mountains, so temperatures didn’t have to fall far for fog to form. That provided some spooky sights amid trees that had shed their leaves.

Fortunately, fog has few lasting weather impacts once the sun rises and the air warms, which burns off that creepy, clingy cloud. But some believe in its staying power, so to speak: a bit of weather folklore portends every fog in August is linked with a snow event the following winter.

We debunked that a few years ago, and for what it’s worth, it says nothing about what October fog foretells. For a more scientifically sound (but decidedly less eerie) insight into what this winter may look like in North Carolina, stay tuned to the Climate Blog as we roll out our Winter Outlook later this month.