If you don’t trust the likes of weather folklore with your winter forecast, here’s a closer look at some environmental factors that might influence our weather this winter, followed by some past years with similar conditions, then our office’s winter outlook.

Current Conditions

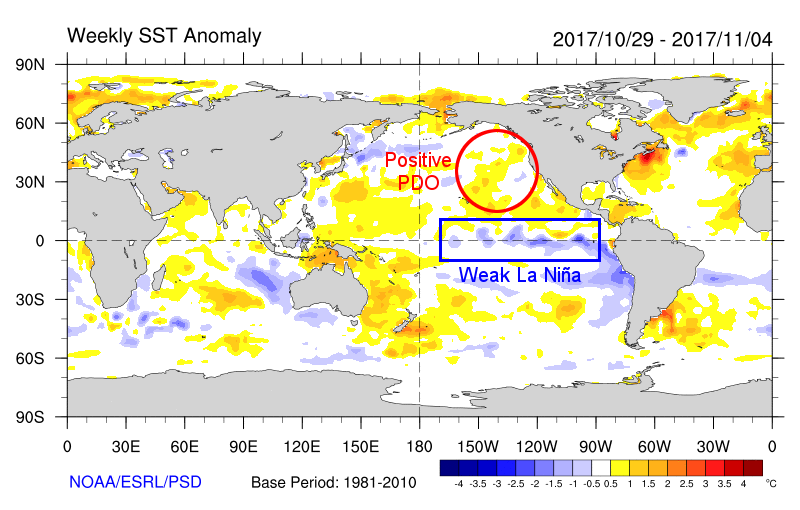

This summer, sea surface temperatures in the central equatorial Pacific Ocean dropped below normal, putting us on the cusp of weak La Niña conditions entering the winter. As part of its atmospheric impacts, La Niñas tend to displace both the polar and subtropical jet stream farther north. This helps weather systems track through the Ohio Valley and away from the Gulf of Mexico, which is where many of our winter storms take root.

Unlike last year, in which the fall La Niña pattern faded early in the winter, we expect this year’s La Niña to hit its peak strength around the middle of the season. And while it may be a weak La Niña overall, its effects have already emerged this fall and should continue into the winter.

Expected Impact: Predominately warm, dry weather

The PDO is another Pacific pattern described by a periodic change in sea surface temperatures across the north Pacific Ocean. The PDO phase can also capture the state of the atmosphere over the north Pacific. For instance, in the current positive-phase PDO, we expect to see more ridging over the western US. That can sometimes encourage troughing in the jet stream over the eastern US, as well as cooler and wetter weather in the Southeast.

When ENSO and PDO are in the same phase, the impacts especially to precipitation across the US can be a bit more potent. However, this winter will see ENSO and PDO in opposite phases — a cool-phase ENSO pattern and warm-phase PDO. As NOAA’s ENSO Blog notes, the precipitation anomalies related to the PDO are weaker than those from ENSO, so we still expect the La Niña-driven pattern to take precedence.

Expected Impact: Possibly some breaks in a dry pattern if jet stream troughs dig down across the Southeast US

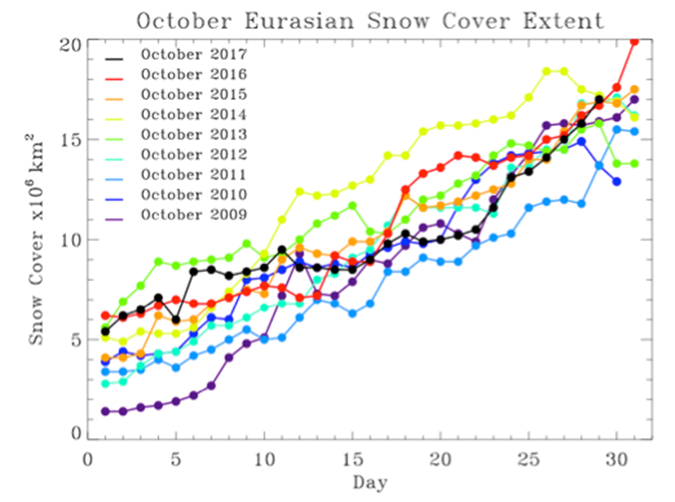

Research suggests that as snow builds up over Siberia during the fall, it cools the air near the surface and warms the upper atmosphere. This can trigger a wintertime weakening of the polar vortex — a permanent upper-level low pressure system — which can cause cold air to sag southward from the Arctic, sometimes reaching North Carolina.

This October was the 11th-snowiest out of the past 50 years in Eurasia. However, an important caveat about this theory says that it’s not just the final snow total that matters; it’s the rate of snow increase during the month. And this year, there was a mid-month lull in the build-up of Siberian snow cover.

That lack of a targeted upper-atmospheric punch could prevent the polar vortex from weakening. Dr. Judah Cohen, the Director of Seasonal Forecasting at Atmospheric and Environmental Research, Inc., suggests that “the long stall in snow cover advance in mid-October” could lead to “a strong [polar vortex]… and a relatively mild winter across the [Northern Hemisphere].”

Expected Impact: Potentially fewer shots of cold weather

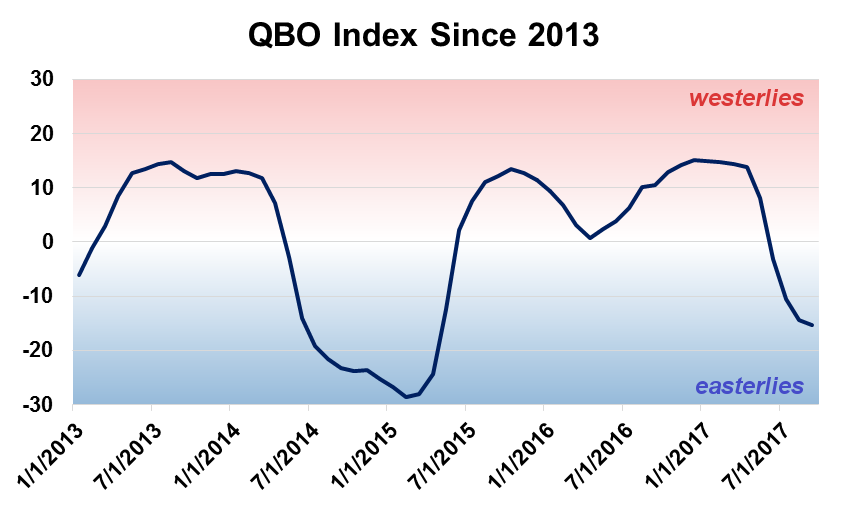

Siberian snowfall isn’t the only atmospheric feature that can affect the polar vortex. Enter the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation, or QBO: a periodic reversal of the wind direction in the stratosphere. Currently, the QBO index is negative, indicating easterly winds aloft.

Every few months, these stratospheric winds tend to migrate downward to the level of the jet stream. As easterlies reach the westerly polar jet stream, they can weaken it, which can also weaken the polar vortex and open the gates for cold air to move southward.

Expected Impact: Potentially more shots of cold weather

Analog Years

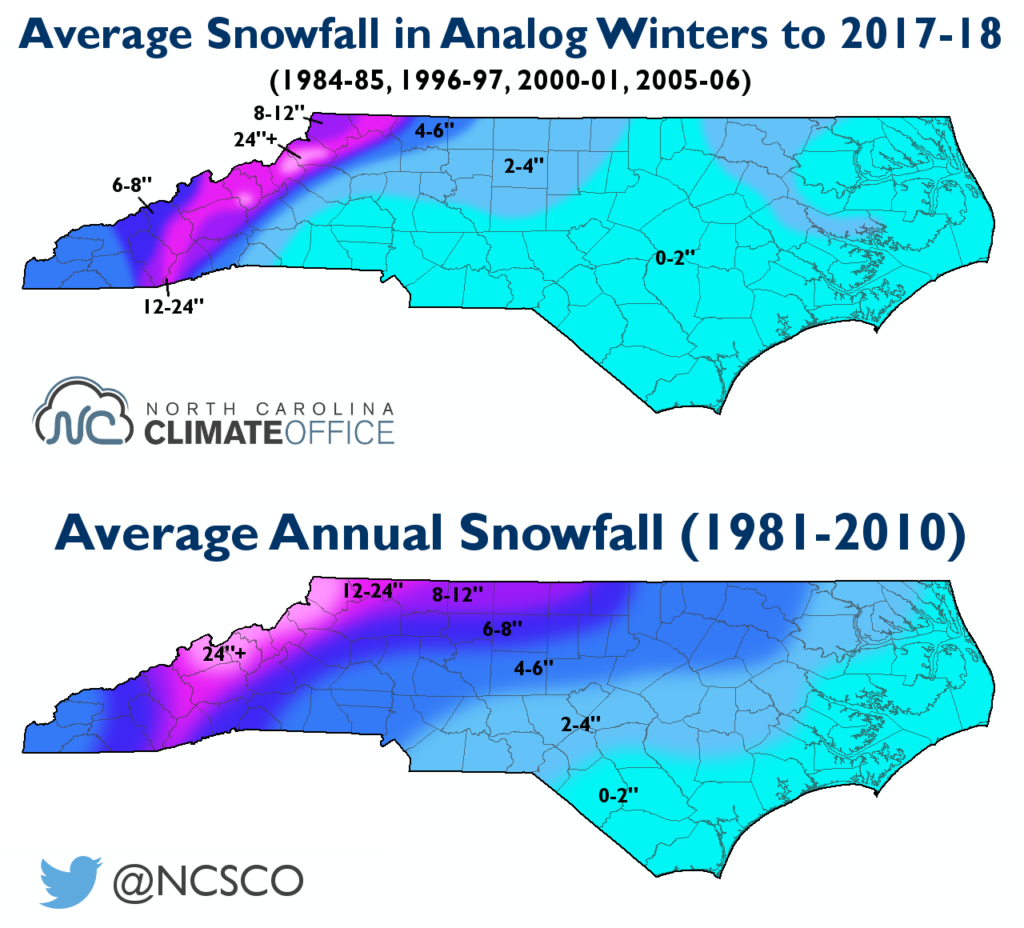

Looking at past years, we identified four with similar conditions in the fall and a similar wintertime evolution of the ENSO pattern as we’re expecting this year. Here’s a summary of how those years played out in North Carolina.

Following a dry fall, we entered the 1984-85 winter with weak to moderate La Niña conditions in place. It finished on the warm and dry side, on average, with only one minor snow event to speak of. However, anyone who remembers January 1985 should recall the record-setting cold weather on “the Coldest Day”. That doesn’t mean a similar event is likely this year, but it is proof that even in a La Niña winter, we can get some cold air with cooperation from the polar vortex.

Wet fall conditions carried into December, and ultimately, that propelled the winter to be slightly wetter than normal. Temperatures were near-normal or above-normal throughout, and as we hit our climatologically most likely time for snow in January, all we saw was an ice storm across the Piedmont.

This December saw cool weather across the eastern half of the country, and a Nor’easter early in the month brought a major snowstorm to parts of the Coastal Plain. After that, though, we steadily warmed up with only one mixed precipitation event across the state in late February.

In a rare instance of a third straight La Niña winter, its typical precipitation impacts were dominant, culminating in our 3rd-driest winter on record. That caused drought to intensify and expand eastward.

Despite a cool, wet December driven by a weak polar vortex, we couldn’t cash in with any major precipitation events. As the polar vortex strengthened in January, warm, dry conditions took hold. The winter finished with near-normal temperatures, on average, as well as dry weather that again led to an increase in Moderate Drought coverage.

| Year | Dec. Ranking | Jan. Ranking | Feb. Ranking | Winter Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984-85 | 5th-warmest | 6th-coolest | 50th-coolest | 31st-warmest |

| 1996-97 | 35th-warmest | 60th-warmest | 17th-warmest | 29th-warmest |

| 2000-01 | 6th-coolest | 50th-coolest | 15th-warmest | 18th-coolest |

| 2005-06 | 31st-coolest | 12th-warmest | 53rd-coolest | 60th-warmest |

| Year | Dec. Ranking | Jan. Ranking | Feb. Ranking | Winter Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984-85 | 10th-driest | 57th-wettest | 30th-wettest | 51st-driest |

| 1996-97 | 49th-wettest | 59th-driest | 59th-driest | 55th-wettest |

| 2000-01 | 12th-driest | 12th-driest | 32nd-driest | 3rd-driest |

| 2005-06 | 29th-wettest | 52nd-driest | 17th-driest | 40th-driest |

Our Winter Outlook

Overall, we expect this winter will be drier than normal with near- to above-normal temperatures in North Carolina due the the La Niña pattern that should remain weak but persistent throughout the season.

As a continuation of our warm fall, we predict warm weather will dominate in December. We expect the best chances for cooler weather will be in January if the polar vortex weakens and the polar jet stream sags southward.

Despite a couple of cold air outbreaks and significant snowfalls in the analog years we examined, we expect to see fewer than normal wintry events. Statewide snowfall events were also uncommon in similar past winters.

With the expected dry pattern, drought is likely to remain and even intensify this winter. Although impacts to agriculture are limited this time of the year, water supply could become a concern since above-normal rainfall is already needed to quench reservoirs across the Piedmont.

While our confidence is low in temperatures later in the winter, it’s always worth remembering that even if we’re in a warmer pattern in February or March, we can never rule out a damaging late-spring freeze event.