This post is part of our year-long series about North Carolina’s weather extremes.

Hurricanes are among the most extreme weather events North Carolina routinely receives. The combination of wind, rain, storm surge, and other hazards packs a major punch, particularly in the strongest storms.

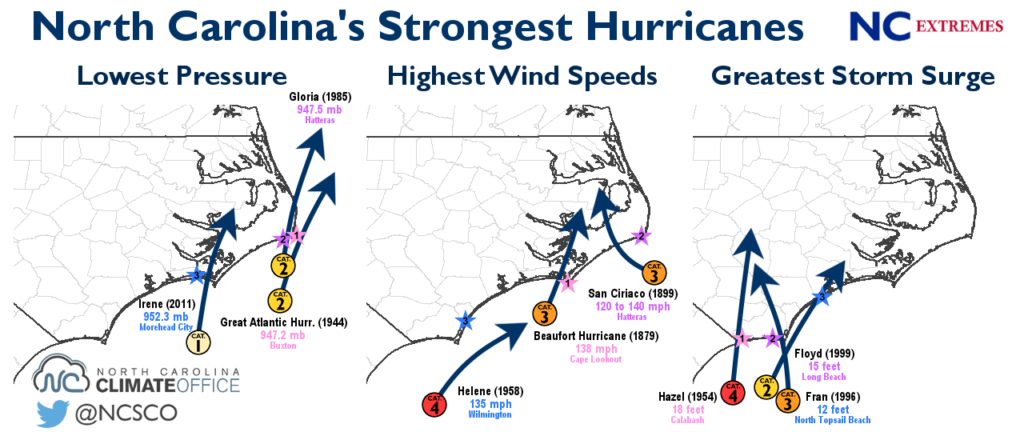

There are several ways to determine the strength of a hurricane. Meteorologically speaking, the lowest pressure and highest wind speeds are often used to assess the strength in and around the eye of a storm. The storm surge can measure the impact of a storm on land, especially along the coast.

Lowest Pressure

The minimum pressure in a storm provides a measure of its intensity from the inside out. Lower pressure is generally associated with higher winds and an overall more mature, better-developed system. However, the minimum pressure is only found in one localized part of the storm, so the hurricanes topping our list of the lowest pressures recorded in North Carolina are ones that passed almost directly over an observing weather station.

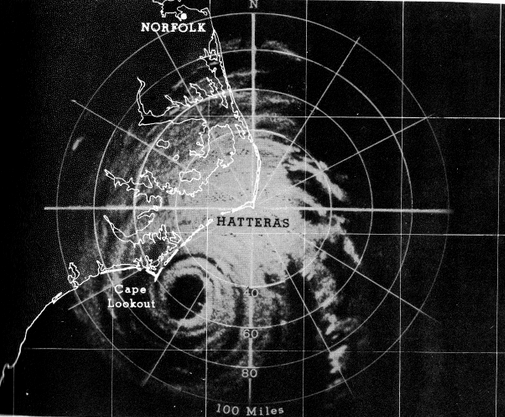

1. Great Atlantic Hurricane (September 1944): 947.2 mb at Hatteras

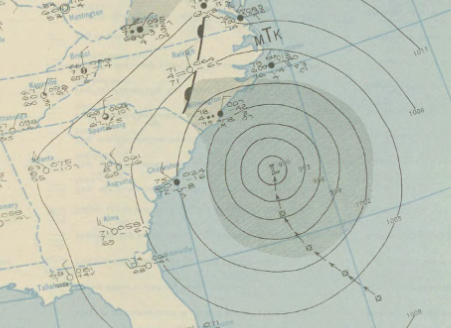

The lowest observed sea level pressure in North Carolina came from the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944, which skirted the Outer Banks on the morning of September 14 at Category-2 strength. The eye passed less than 10 miles from Cape Hatteras, and an observer recorded a pressure of 947.2 millibars.

Winds peaked at an estimated 90 mph with gusts up to 110 mph, and the storm tide rose to 5 feet at Hatteras. Farther up the coast, hurricane-force winds destroyed 108 buildings and damaged more than 600 others from Nags Head to Elizabeth City.

Coastal farms were also flooded, resulting in hundreds of thousands of dollars in losses of corn and other crops. One death and four injuries were reported in North Carolina. The storm continued to parallel the east coast before making landfall on Long Island, New York, and causing hundreds of millions of dollars in damage to the Northeast US.

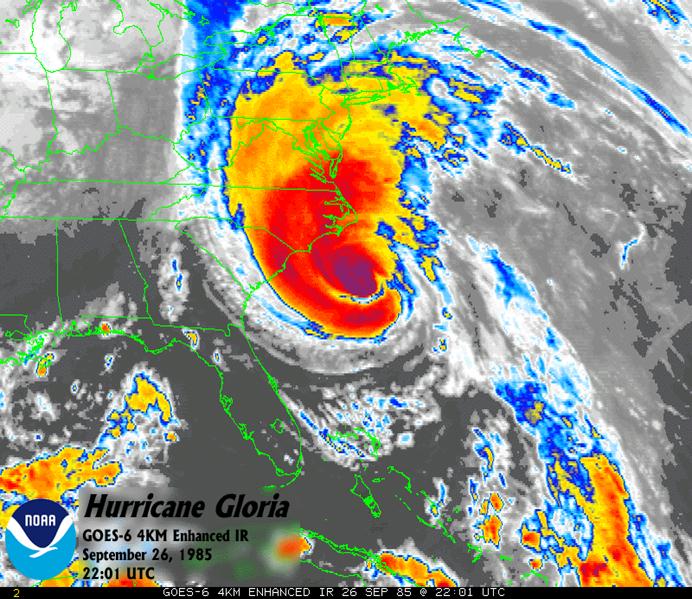

2. Hurricane Gloria (September 1985): 947.5 mb at Buxton

A storm with a similar track and strength ranks second on the list. In 1985, Hurricane Gloria approached the Outer Banks from the south as a Category-2 storm.

Shortly after midnight on September 27, Gloria made landfall along the southern end of Hatteras Island. The Weather Service Office in Buxton reported a minimum pressure of 947.5 millibars, along with maximum sustained winds of 74 mph.

Gloria was an even stronger storm earlier in its life. As it passed north of Hispaniola as a Category-4 hurricane, its minimum central pressure was measured at 919 millibars — at that time, the lowest ever recorded by reconnaissance aircraft.

It weakened as it turned north but still packed a punch as it brushed the Carolina coast, bringing beach erosion and flooding to the Outer Banks. Like the 1944 hurricane, Gloria then set its sights on the Northeast US, where it resulted in downed trees, power outages, eight deaths, and nearly $1 billion in damage.

3. Hurricane Irene (August 2011): 952.3 mb at Morehead City

A more recent storm slots into third place on the list. Hurricane Irene in 2011 dropped the sea level pressure to 952.3 mb at the Morehead City Airport as it made landfall near Cape Lookout on August 27 at Category-1 strength.

As Irene continued up the coast, several other sites reported similarly low pressure values: 953.3 mb at Cape Lookout, 955.1 mb at Cherry Point, and 957.1 mb at Elizabeth City. A maximum wind gust of 115 mph was observed at Cedar Island.

Irene delivered a variety of hazards to eastern North Carolina. Along with hurricane-force wind gusts, the Outer Banks saw severe beach erosion and several breaches of Highway 12 on northern Hatteras Island. Farther inland, Irene spawned tornadoes, brought heavy rain — Bayboro received 15.74 inches in just two days — and caused more than 600,000 power outages.

Highest Wind Speeds

We have confidence that our weather sensors can accurately capture even extreme hot and cold temperatures, but record wind speeds often test the limits of the instruments that measure them. Many hurricane reports even in recent years remark that winds were measured until the anemometers were destroyed or blown away. Because of that, the extreme wind speeds on the list below probably don’t tell the full story about the fury of those storms.

1. Great Beaufort Hurricane (August 1879): 138 mph at Cape Lookout

To find the highest known official wind speed in North Carolina, we have to go back 136 years. During the Great Beaufort Hurricane of 1879, Cape Lookout reported a maximum wind speed of 138 mph. The anemometer cups broke after that reading, and it’s said that the winds were even stronger — perhaps up to 165 mph — in the hours that followed.

That storm made landfall near Morehead City as a Category 3 on the morning of August 18. It destroyed two hotels along that section of the coast and damaged railroad tracks, homes, wharves, and ships. Up and down the coast, other observing stations reported hurricane-force wind speeds — 100 mph at Kitty Hawk, 97 mph at Portsmouth, 74 mph at Hatteras — before their anemometers broke or were blown away as well.

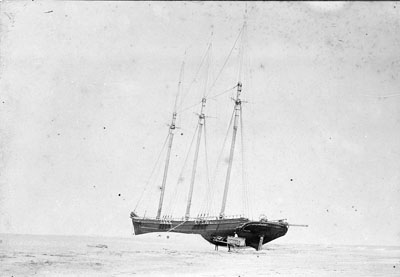

2. Hurricane San Ciriaco (August 1899): 120 to 140 mph at Cape Hatteras

Twenty years later, another strong Category-3 storm hit the coast and lashed it with high winds. In 1899, the storm unofficially called Hurricane San Ciriaco because of the holiday when it struck Puerto Rico eventually reached the Carolina coast, bringing gusts of 120 to 140 mph at Cape Hatteras.

At that point, the eye was 40 miles offshore, so it’s likely that higher gusts occurred that evening as it made landfall on the north end of Ocracoke Island. However, the strong gusts plus sustained winds of up to 93 mph earlier in the day knocked out the anemometer at Hatteras.

Weather Bureau observer S. L. Dosher noted: “This hurricane was the most severe in the history of Hatteras. The scene on the 17th was wild and terrific.” A sound-side storm surge flooded the island to a depth of 4 to 10 feet, “carrying everything movable before it”. It flooded most homes and drowned livestock, and the fishing industry was “swept out of existence”. At least 20 deaths were reported in North Carolina.

Along with its intensity and damage, this storm is remembered as the longest-lived in the Atlantic basin, surviving for just over a month. It moved through the Caribbean as a Category-4 hurricane and remained at Category-3 strength until making landfall in North Carolina. After moving back out to sea, it meandered across the North Atlantic for two more weeks before losing tropical characteristics near the Azores.

3. Hurricane Helene (September 1958): 135 mph at Wilmington

Hurricane Helene isn’t a household name, but it came awfully close to becoming one when it skirted the North Carolina coast in 1958.

The eye of Category-4 Helene passed just 20 miles southeast of Cape Fear, setting Wilmington‘s all-time record wind gust of 135 mph accompanied by sustained winds of 85 mph. Along Cape Fear, wind speeds were estimated at 125 mph with gusts perhaps reaching 150 to 160 mph.

Helene caused about $11 million (1958 dollars) in damage in North Carolina, with most of the damage confined to the immediate southern coast. However, the damage could have been much worse if the track had shifted slightly west, exposing the coast to the powerful right-front quadrant of the storm, where the combination of the storm’s high winds and forward speed often results in the worst damage.

The Weather Bureau’s recap of the storm noted that “the Carolina coast missed a potential disaster of the first magnitude by a very narrow margin”, and the National Weather Service in Wilmington remarked that “had Helene actually made landfall we would likely make comparisons to Helene, not Hazel, when discussing worst-case hurricane scenarios for Wilmington.”

Greatest Storm Surge

In terms of on-the-ground impacts, one of the most telling measures of hurricane intensity is the storm surge. Although it can vary based on other factors like the tide level and the angle of approach, strong landfalling storms tend to have greater storm surge.

1. Hurricane Hazel (October 1954): 18 feet at Calabash

One of the most devastating storms for the North Carolina coast was Hurricane Hazel in 1954. Hazel’s eye came ashore on the morning of October 15 near the South Carolina border, and the storm surge peaked in nearby Calabash at an incredible 18 feet.

As we covered in our summary of Hazel on its 60th anniversary last year, the tremendous storm surge was the result of several favorable factors, including its high winds, forward speed of nearly 60 mph, and the high lunar tide. Most of the southern coast was overrun with a surge of at least 12 feet, wiping away or severely damaging most structures.

Hazel would almost certainly rank near the top of the low pressure and high wind speed rankings if official measurements were available from the affected areas. Unofficially, a pressure of 937.9 millibars was observed on a fishing boat near Little River, South Carolina, and wind gusts along the southern coast were estimated at up to 150 mph.

2. Hurricane Floyd (September 1999): 15 feet at Long Beach

One of the most memorable recent hurricanes for eastern North Carolina is Hurricane Floyd from 1999. When it made landfall early on September 16, Floyd battered the coast as a strong Category-2 hurricane and delivered a storm surge of up to 15 feet at Long Beach on Oak Island.

As with Hazel, the timing of Floyd’s landfall coincided with the high tide, which made its storm surge even higher. Along the southern coast, a 9 to 10 foot surge flattened sand dunes and buildings. Roads along the coast, including Interstate 40 near Wilmington, were also flooded.

Of course, Floyd’s impact didn’t end at the coastline. As it continued up the coast, it dropped more than 10 inches of rain. The ground was already saturated after Hurricane Dennis’ landfall just 11 days earlier, so the water ran off into rivers and streams. The Tar and Neuse rivers reached record-settling levels and surrounding communities suffered devastating flood damage.

3. Hurricane Fran (September 1996): 12 feet at North Topsail Beach

Another storm fresh on the minds of many in North Carolina is Hurricane Fran from 1996. Although Fran made landfall near the South Carolina border, it was a large storm with fierce Category-3 winds and damaging effects far from the eye. On the north side of Cape Fear, where Fran’s eye came ashore, the storm surge peaked at 12 feet at North Topsail Beach.

That area was still recovering from Hurricane Bertha two months earlier. Bertha flattened sand dunes, which made it easier for Fran’s surge to come ashore. Homes and roads in Wrightsville Beach, Carolina Beach, and Kure Beach were filled with up to 6 feet of sand and water.

On Topsail Island, Fran cut a 100-foot-wide inlet and knocked out homes and roads. At North Topsail Beach, the storm destroyed the temporary police station constructed after Bertha, and the beach and nearby marsh were left littered with debris.

Of course, pressure, winds, and storm surge aren’t the only signals of a strong storm. Damage can also be an indicator of strength, but it varies based on the area affected, the development (or lack thereof) in that region, and other factors. Because of these complexities, we will cover North Carolina’s most damaging and deadly hurricanes in October’s NC Extremes blog post.

Sources:

- Monthly Weather Review archives from NOAA

- North Carolina Hurricanes by Albert Hardy and Charles Carney, US Weather Bureau (1962)

- Top 20 Storms in Wilmington, North Carolina’s History by Tim Armstrong, NWS Wilmington