Five years ago, an overactive Atlantic brought an early-season hurricane to North Carolina’s doorstep.

Just after 11 pm on August 3, 2020, Hurricane Isaias made landfall as a Category-1 storm near Ocean Isle Beach along our southern coastline.

Sneaking in overnight during a year dominated by other big news stories, Isaias and its impacts weren’t a mainstay in our headlines. Based on the statistics, it’s even tempting to dismiss Isaias as an insignificant or forgettable storm.

As hurricanes go, it was relatively weak, peaking at Category-1 intensity during its life that began as a long-lasting tropical wave crossing the Atlantic before finally becoming a named tropical storm on July 29.

And as the third landfalling hurricane in a three-year period for North Carolina, Isaias is naturally compared against its stronger and more damaging predecessors: the record flood-producing Hurricane Florence in 2018 and the coastal menace of Hurricane Dorian in 2019.

But a hurricane of any intensity is still a robust weather event, and Isaias brought its own unique challenges, particularly for storm-weary eastern North Carolina, along with changes in how we prepare for and respond to tropical events as a state.

A New Year, Another Storm

Typically, the tropical Atlantic is just waking up by early August, with only two named storms, on average, in the first two months of the hurricane season.

But Isaias was the record-breaking ninth named storm to form before the end of July, and that early activity, together with the recent hits from Florence and Dorian, had eastern North Carolina on high alert entering the 2020 hurricane season.

With so many storms so close to home, forecasters had gained plenty of experience with landfalling hurricanes by the time Isaias developed. It helped that Isaias was a well-forecasted storm for which we had plenty of lead time.

“The National Hurricane Center did an outstanding job messaging this storm over a week before the impacts in the Carolinas,” said Tim Armstrong, a senior meteorologist at the National Weather Service in Wilmington who has spent his entire 24-year career at that office, and previously interned at the Wakefield, VA, office during Hurricane Floyd.

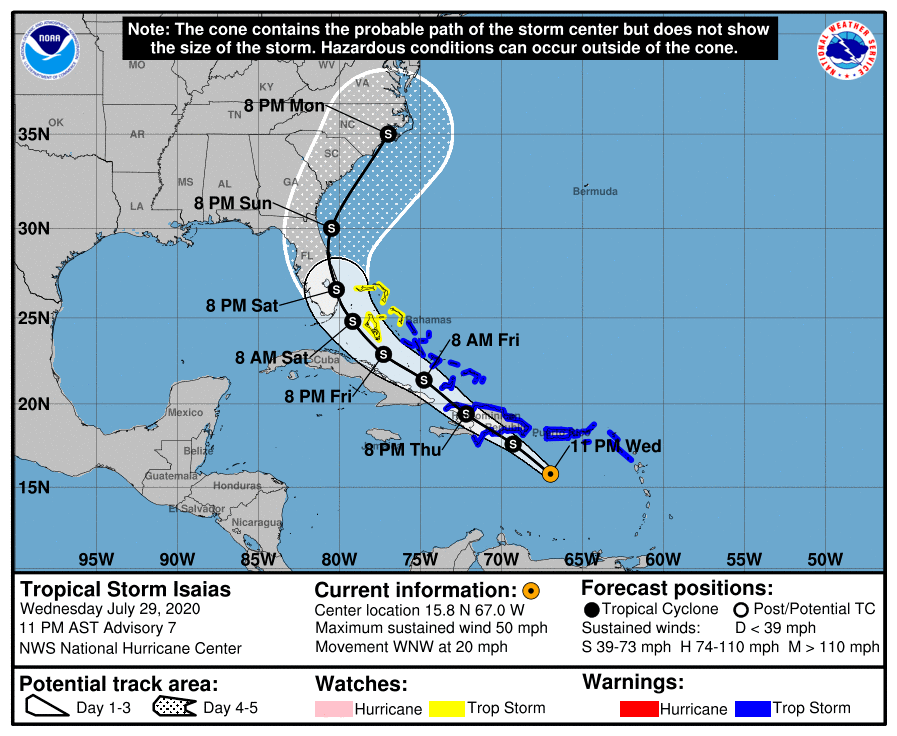

As early as July 23, the National Hurricane Center began tracking the tropical wave that later became Isaias, and on the same night it became a named storm, the five-day forecast showed it heading toward North Carolina’s southern coastline.

“Given the forecast that we saw three, four, and five days in advance, we were looking at the potential for heavy rain, tornadoes, and even storm surge,” said Armstrong.

While the experience during Florence and Dorian helped with messaging about the incoming Isaias, that storm’s exact impacts – and the areas experiencing them – would be unique from its predecessors.

“Far eastern North Carolina had stronger winds from Dorian that we missed in the Cape Fear area, and Florence was more of a heavy rain and flooding event,” added Armstrong.

While Isaias’s intensity oscillated between a strong tropical storm and a weak hurricane as it moved northward out of the Bahamas, forecasts locked in on a fast-moving storm making landfall along our southern coastline and speeding northward across the Coastal Plain.

That would mean less rain and flooding, but a bigger storm surge and potentially strong tornadoes within its outer rain bands.

Putting Plans into Place

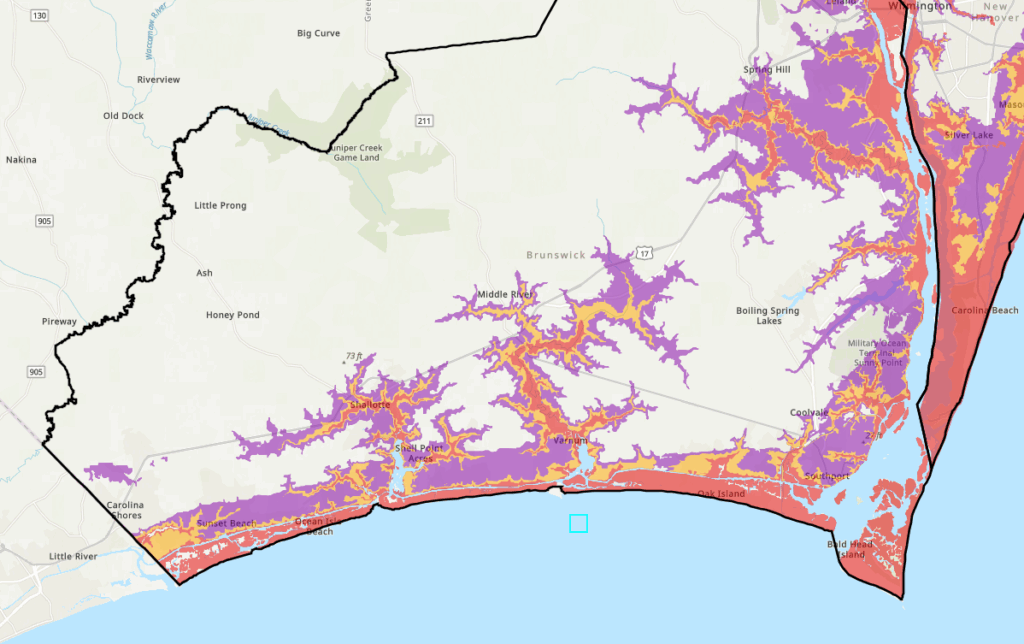

The expected storm surge meant evacuations were likely, and that would put a new procedure into practice. Since 2016, when a Hurricane Evacuation Study was completed by FEMA and the US Army Corps of Engineers, North Carolina Emergency Management (NCEM) had been working on updates to the state’s storm evacuation protocols, which became the Know Your Zone system.

“Until Know Your Zone was implemented, North Carolina was the only hurricane-prone state to not have a formal evacuation process in place,” said Diana Thomas, the Natural Hazards Branch Manager, and Katie Webster, the Assistant Director for Plans at NCEM, in comments shared with the State Climate Office.

“Prior to the Know Your Zone implementation, evacuations were ordered from local officials by using delineation of areas based on towns, roadways, or cross streets.”

After considering inundation maps from the National Hurricane Center and meeting with local and county officials to determine the areas most susceptible to flooding, NCEM developed the tiered zone system – from Zone A, which is evacuated first, to Zone E, which is evacuated last, if at all.

That limits over-evacuation, helps inform sheltering and transportation resource positioning, and gives coastal residents an easy-to-remember letter to listen for when a storm is approaching.

“While all zones won’t be evacuated in every event, emergency managers will work with local media and use other outreach tools to notify residents and visitors of impacted zones and evacuation instructions,” noted Thomas and Webster.

After being piloted within three counties in 2019, the Know Your Zone system was rolled out in all 21 coastal counties for the 2020 hurricane season, and Isaias would be its first test.

The storm would challenge one more unprecedented aspect of 2020. Amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, restaurants and other businesses had reopened in North Carolina with up to 50% occupancy that summer, but big crowds were still discouraged.

With the potential for evacuees turning up en masse at shelter locations, the North Carolina Department of Public Safety (NC DPS) implemented its own preparedness measures, which included Covid screenings, face coverings, and social distancing at shelters.

Looking back, another measure stands out for Todd Brown, the Assistant Director of Operations with NC DPS.

“The most memorable for me was the non-congregate sheltering piece, as this was the first real exercise for that process,” said Brown. “We had a pretty solid plan, with over 2,500 hotel rooms blocked and contracted, and a feeding and case management plan with the American Red Cross.”

With a new evacuation system in use and new precautions in place to keep people safe who were seeking refuge from the storm, all that remained was waiting for Isaias to arrive.

A Strengthening Storm Arrives

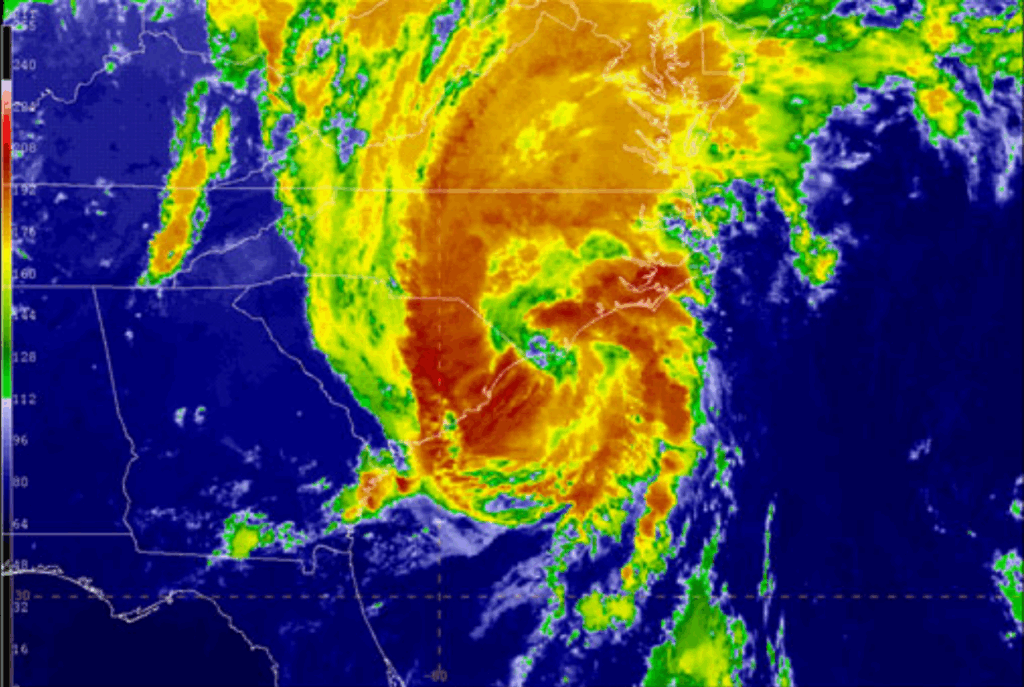

As Isaias approached on the evening of Monday, August 3, the storm had an uptick in intensity, with its maximum sustained winds increasing from 75 to 85 miles per hour. While still a Category-1 hurricane, it was a hurricane nonetheless, as our coastline was about to find out.

The first points of impact in the state were the coastal communities of Brunswick County, from Calabash in the west to Bald Head Island in the east, and hurricanes were also fresh in the memories of residents there after Hurricane Matthew less than four years earlier.

“Matthew was close enough that the Brunswick County beaches had significant storm surge impacts, in some cases several blocks from the beaches themselves,” said Armstrong.

As Isaias made landfall in the center of that 35-mile-long sandy stretch, the county sustained a variety of damage, from the surf-stricken pier at Ocean Isle Beach to cars carried by the storm surge on Oak Island, where wind gusts were measured at up to 87 miles per hour, to boats piled up in the marina and marshes around Southport.

Isaias’s landfall lined up with the high tide on a full-moon night, which made the incoming waves even higher. In fact, the water rushing up the mouth of the Cape Fear River pushed the downtown Wilmington river gauge to its record high crest, later confirmed at 9.03 feet – beyond what it hit during Florence or Floyd, and even past the levels during Fran and Hazel.

“My main memory was how intense that storm surge was,” said Armstrong. “We saw the full fury of what that storm could produce.”

But Isaias’s impacts didn’t stop there. Even after being downgraded to a tropical storm once the storm’s center moved over land, it was still a potent wind-maker, with gusts of more than 40 miles per hour observed east of Interstate 95, and thunderstorms embedded in its outer bands had already begun spawning strong tornadoes.

While tornadoes are fairly common during landfalling hurricanes – Floyd, which also came ashore in Brunswick County, spawned 16 of them in the state – they tend to be weak and short-lived.

An analysis by NWS Wilmington found that among 92 tropical-related tornadoes in their county warning area between 1991 and 2021, all but four were rated as EF0 or EF1 – the lowest two categories on the Enhanced Fujita scale.

But with thinner rain bands and a trajectory taking it due north out of the warm tropics, Isaias had unlocked the ingredients for strong severe weather, including tornadoes.

“One of the limiting factors with tropical cyclones is that with the cloud cover, you don’t see the instability to get strong updrafts. This storm put eastern North Carolina in an onshore flow pattern with the warmest sea surface temperatures of the year just offshore. That meant it would have access to plenty of unstable air,” said Armstrong.

In addition, strong winds and high wind shear – or the change of wind speed and direction with height – made for overturning air at low levels that could be tilted vertically by updrafts to form tornadoes.

The first bunch of five tornadoes touched down in Brunswick County, including an EF2 that damaged homes and businesses along its track from Bald Head Island through Southport. Five others at EF1 intensity then hit Pamlico, Martin, and Beaufort counties.

And as Isaias raced northward, its hardest hit was still to come.

Damage Amid the Darkness

Bertie County is in our northern Coastal Plain, more than 150 miles from where Isaias made landfall, but that area is no stranger to hurricane impacts. The county seat in Windsor sits on the banks of the Cashie River, and it experienced repeated flooding during Floyd, Matthew, and even the remnants of Tropical Storm Julia in 2016.

Isaias unleashed a different hazard on the county, with a tornado touching down south of Windsor at 1:15 am and tracking to the northwest across a 10-mile stretch, including through the Cedar Landing community.

A storm survey by the NWS Wakefield office determined it had a maximum EF3 intensity with peak winds of 140 to 145 miles per hour, making it the strongest tornado spawned by a tropical system in the US since Hurricane Rita in 2005.

The tornado damaged or destroyed dozens of mobile homes and single-story homes, killing two people and injuring up to 20 others.

Even in the middle of the night, first responders were quick to spring to action. A release by Bertie County Emergency Management noted that “crews were on the scene before the storm passed over,” battling winds, rain, and downed trees to reach affected areas.

After that, other state services came into play, both in Bertie County and in hard-hit southern coastal areas such as Oak Island.

“We opened two reception centers in Nashville and Lumberton where evacuees could arrive and be placed in a hotel room,” recalled Brown from NC DPS. “We did place a few folks from Bertie County that ended up becoming long-term due to their homes being damaged or destroyed by the tornado, and a handful from Brunswick County were temporarily placed in non-congregate sheltering as well.”

Evacuees also included residents within Zone A on the Outer Banks, which encompasses Hatteras and Ocracoke islands, along with those in Holden Beach, Ocean Isle Beach, and Caswell Beach in Brunswick County.

In the wake of the storm, more than 200,000 electrical customers in the state were without power, including 53,000 in Brunswick County and 85,000 in New Hanover County, per the National Hurricane Center’s report on Isaias.

A Shift in Tropical Impacts

In hindsight, Isaias was something of a milepost in North Carolina’s hurricane history, marking the end of one era of local tropical activity and setting the stage for a different flavor of storms in the half-decade since then.

It was the third of three landfalling storms along our coast in a three-year period, and the fourth significant coastal hurricane – counting Matthew, which never made landfall in North Carolina – in less than five years.

That spate of storms helped inspire and hone the state’s new evacuation system, which got its first major test – fortunately, across relatively few zones – during Isaias.

“There were localized evacuations both during the pilot program and during Isaias that were publicized on social media and broadcast networks within the impacted areas,” said Thomas and Webster from NCEM.

And the circumstances of a pandemic forced the state to get creative with safely accommodating evacuees, which led to the implementation of non-congregate shelters in hotels. In that sense, the response was a success, and also a bullet dodged compared to the scale of Isaias’s predecessors.

“Isaias was a good test, and I was pretty confident in the system we worked out because of the COVID restrictions,” said Brown from NC DPS. “But we would have been limited to a maximum of around 12 to 15,000 evacuees. In Florence we had about 50,000 in shelters.”

The past five years have still seen plenty of tropical activity in North Carolina, but much of it has been further inland. Later in the 2020 hurricane season, western North Carolina was affected by the remnants of a half-dozen storms, including Delta and Zeta — names pulled from the Greek alphabet due to the abundant activity that year.

Since then, the Mountains were hit hard by Tropical Storm Fred in 2021 and Hurricane Helene in 2024, and in the Piedmont saw flooding and damage from Tropical Storm Debby in 2024 and Tropical Storm Chantal just last month.

Lessons Learned After Isaias

That break has given coastal areas affected by Isaias and its predecessors a chance to rebuild. On Oak Island, which suffered at least $10 million in damage, repairs were completed to the Yaupon Pier thanks in part to funds from the state Disaster Recovery Grant Program. FEMA provided $1.3 million for debris removal, and the town also rebuilt marsh walkovers that were damaged by the storm.

Despite the recent calm at the coast, state officials have further tested and refined our protocols for major weather events, including evacuations.

“Taking experience from the storms since Isaias, we’ve learned that our messaging needs to be a statewide approach,” said Thomas and Webster. “For example, Helene largely impacted western North Carolina, but impacts were felt across central and eastern North Carolina as well that required localized evacuations where evacuation zones aren’t currently implemented.”

They added that coastal counties have the opportunities to adjust their evacuation zones each year, and several have included more riverine areas at risk of freshwater flooding, as illuminated by those recent events.

Practices put into place during Isaias have also proven useful during the latest batch of storms in western North Carolina. In particular, non-congregate sheltering was used again during Fred, and that storm showed the utility of such an option.

“Non-congregate sheltering is good for social distancing and for longer, short-term housing needs. It’s not great for evacuation,” said Brown. “For most events that cause damage to residences. we eventually start non-congregate sheltering as transitional sheltering to get folks that can’t go back to their homes out of the shelters in churches and schools.”

With recovery in various stages of completion after Helene, Fred, and Isaias, we’re now heading toward the peak of a new hurricane season that has already sent one flooding storm our way, keeping with the recent trends of big impacts and heavy rain farther inland.

As surprising as it sounds, a full five years after it hit in August 2020, Isaias remains our latest landfalling hurricane in North Carolina.

While that event reminds us of how damaging even a low-end hurricane can be in coastal areas, the damage in Bertie County also shows that a storm of any strength can have potent localized impacts far from the point of landfall.

That lesson is fresh for all of North Carolina after a destructive half-decade, including and since Isaias.