This post is a summary of our recent Year in Review webinar. The recording from that event will be posted soon, and the presentation slides are now available.

North Carolina’s weather in 2024 featured the costliest and deadliest tropical storm in our state’s history; that alone made it a notable year. But beyond Hurricane Helene, it was a year of extremes, contrasts, and other impactful events in our weather and climate.

Looking back on the past year in this post, we cover key statewide and local rankings, the major weather storylines in North Carolina, and 2024 in perspective of the state-level and global climate.

Annual Rankings and Monthly Progression

The National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) has released the final data for 2024, and it shows a statewide average temperature of 61.5°F, which ranks as our 2nd-warmest year on record in North Carolina, barely behind our warmest year in 2019.

That means five of our state’s top six warmest years have happened since 2016, and each year in the past decade ranks among the top 22 warmest on record dating back to 1895.

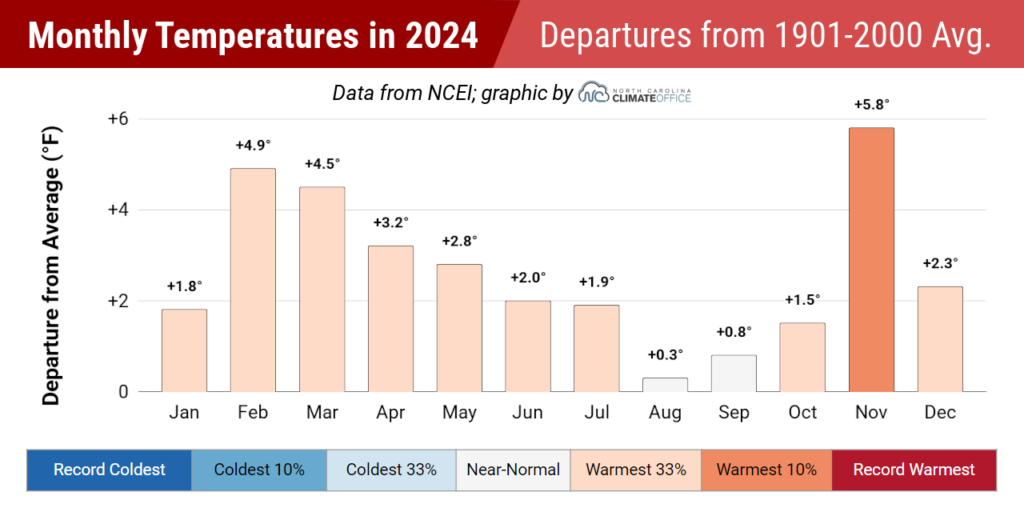

Notably, all twelve months in 2024 were warmer than the historical average statewide. That’s only the third time for such an occurrence in a calendar year, joining 1998 and 2017.

Early in the year, that warmth was manifest in another snow-free winter for much of the state that saw spring-like temperatures by February. Extreme heat set in by the early summer and unseasonable warmth returned in the fall, particularly in our 3rd-warmest November on record.

A few local weather stations did record their warmest years on record, including Asheville, Hickory, and Raleigh, while in Charlotte, 2024 tied 1990 as the warmest year. Many other sites including Murphy (3rd-warmest), Greenville (3rd-warmest), and Wilmington (5th-warmest) had one of their top five warmest years last year.

Per NCEI, the statewide average precipitation of 53.01 inches put 2024 as our 31st-wettest year out of the past 130 years. After three consecutive drier-than-normal years, it was our first overall wet year since 2020.

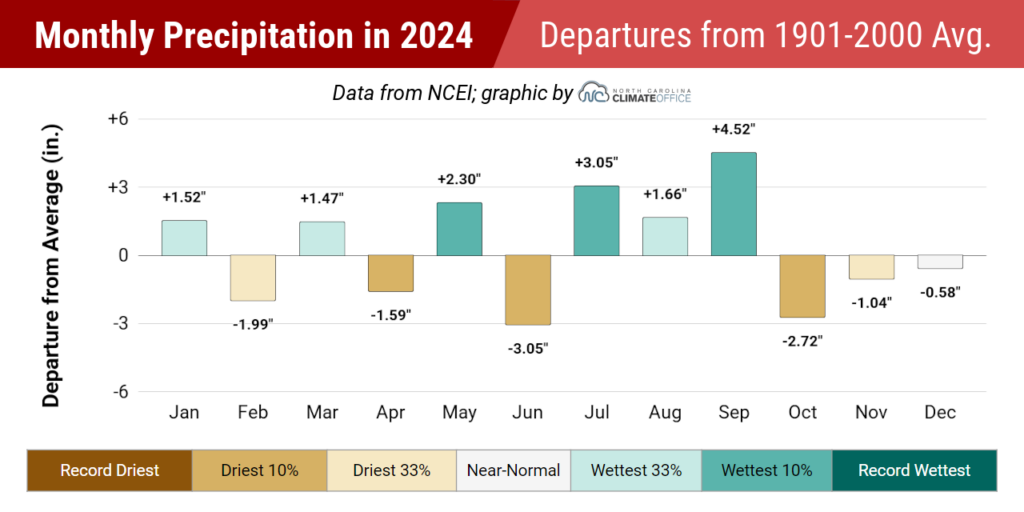

However, the story of our precipitation in 2024 was its variability, both over time and space. The first six months of the year alternated between wet and dry, culminating in the 2nd-driest June on record statewide.

A wet end to summer – featuring our 6th-wettest July and 8th-wettest September – was followed by a sudden switch to a dry fall, including our 3rd-driest October on record.

Locally, it was one of the top ten wettest years for several western sites soaked by Helene, including the 3rd-wettest year for Asheville, the 5th-wettest in Shelby, and the 7th-wettest in Marion.

Despite being away from the heaviest tropical rainfall, it was still an overall wet year for parts of the Piedmont, including the 7th-wettest year on record for Greensboro, the 18th-wettest in Raleigh, and the 27th-wettest in Charlotte.

At the coast, the dry end to the year left many eastern sites below their normal annual precipitation. It finished as the 30th-driest year on record in New Bern, the 36th-driest in Edenton, and the 59th-driest out of 110 years for Fayetteville.

Major Weather Stories

As the monthly temperatures and overall annual ranking indicate, one storyline in 2024 was the prevailing warmth. That was also evident with daily record temperatures in all four seasons, from a springlike 72°F on February 10 in Asheville to a sizzling 88°F on April 2 in Goldsboro to a balmy nighttime low of only 74°F in Greensboro on June 23 to Oconaluftee’s latest 80-degree day on record on November 9.

That warmth was also apparent throughout the growing season, including the first freeze-free March for Wilson since 1945 and a record-long 281-day freeze-free season in Raleigh that ended with a delayed first fall freeze on November 29.

Another characteristic of our 2024 climate was multiple drought events – including the continuation of snow droughts to record lengths in areas such as Asheville and Charlotte. Snow in early December or this January finally ended many of those snow-free streaks, but some eastern sites have still been waiting more than 1,000 days since their last measurable snow.

Meteorological drought, defined by below-normal precipitation and its impacts, was also an issue throughout the year. Several weeks of hot, dry weather in June saw a rapid expansion and intensification of drought conditions that devastated the corn crop and led to restrictions being implemented by some eastern water systems.

In the fall, the drought in eastern North Carolina – spurred on in part by the lack of local tropical rainfall after the peak of hurricane season – delayed some cover crop planting, while dry weather in the west on the heels of Helene fueled large wildfires as late as December, including a 664-acre fire at Crowders Mountain State Park and a 518-acre fire near Lake Tahoma.

Overall, wildfire activity across the state was about average last year following an active fire year in 2023. The North Carolina Forest Service reports a preliminary total of 4,680 wildfires burning 17,220 acres on state and private lands in 2024; each of those statistics ranks near the middle of the past 10 years.

In between our summer and fall droughts, we dealt with heavy rain and storms, especially when the tropics sprung to life in August and September. The slow-moving Tropical Storm Debby drenched the eastern two-thirds of the state in August, causing flooding as far west as Charlotte and roadway and dam failures in Fayetteville.

A month later, the unnamed Potential Tropical Cyclone Eight produced up to 20 inches of rain along parts of the southern coastline, including Southport and Carolina Beach.

And just two weeks after that, western North Carolina saw its most destructive event ever when Hurricane Helene and its predecessor frontal event dropped more than 30 inches of rain and lashed the region with gusty winds. The National Weather Service in Greenville, SC, found evidence of widespread hurricane-force gusts northeast of Asheville, including the 106-mph peak wind reported by our Mount Mitchell ECONet station.

Four months following Helene, recovery is only beginning, some roads remain closed including Interstate 40 along the Tennessee border, and the damage is now estimated at $53.6 billion. The death toll in the state stands at 104, which is also a record for a tropical storm in North Carolina.

Helene’s impacts included ten tornadoes as far east as Rocky Mount. Those were part of an annual total of 42 confirmed tornadoes in 2024, which was the most in a year since 2020. That included a pair of tornadoes on May 8 in Jackson County, which only had three other tornadoes in the previous 74 years, and multiple EF-3 tornadoes in a year for the first time since 2011.

With periods of severe drought immediately followed by heavy rain and flooding, 2024 featured more examples of weather whiplash. That’s a term we coined back in 2021 to describe the quick, unpredictable changes in our weather, particularly between wet and dry spells.

Even in the spring, the oscillation between wet and dry months created challenges for farmers, whose fields alternated between being too wet to work in and too dry for planting. The impacts to agriculture stepped up over the summer when flash drought fried the corn crop, with an estimated 60% production loss to the tune of $302 million.

In places like Columbus County, which was classified in Extreme Drought on the US Drought Monitor for the first time since 2011, that early July drought was followed by flooding from Debby just one month later.

Those quick changes are also evident in local statistics. In Greenville, June ended with 23 consecutive days without rain – the longest dry streak locally since 2000 – and was followed by the wettest July on record, including six consecutive wet days with more than 7 inches of rain in total. Meanwhile, Morganton followed its 4th-wettest September on record, punctuated by Helene, with its 3rd-driest October.

The Year in Perspective

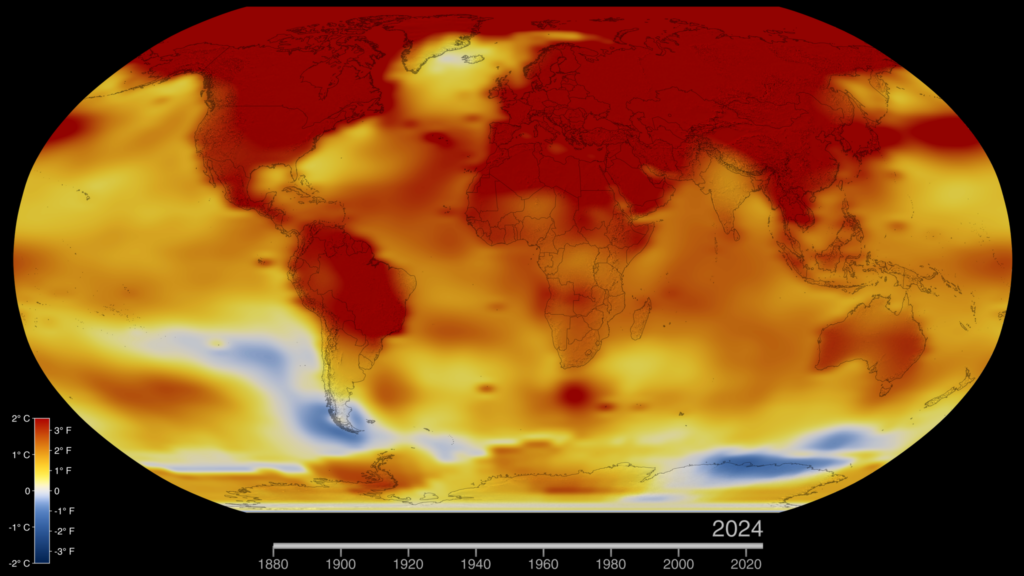

It wasn’t just North Carolina feeling the warmth last year. According to independent analyses from NOAA and NASA, 2024 was the Earth’s warmest year on record. If that sounds like a familiar headline, that’s because it is: 2023 had previously set the record, and each of the planet’s ten warmest years since 1850 have all occurred in the past decade.

The local manifestation of that warmth had a few unique characteristics that tell us as much about where our climate is now as it does about where we’re going. As explained in the previous section, all twelve months were warmer than average statewide: a sign of the background warming in all seasons that the North Carolina Climate Science Report notes is very likely to continue in the future due to climate change.

We also saw the encroachment of our “shoulder seasons” into the traditional cool season, with spring flowers blooming by February and a freeze-free fall lasting through late November in some areas.

When our 90-degree days kicked in by early May, it was a sign of things to come over the next two months, as summer surged in unusually early last year. Offshore high pressure and relentless jet stream ridging meant the heat was truly on by June, with sites such as Raleigh and Smithfield recording triple-digit temperatures and their warmest days since 2012.

In Raleigh, the heat reached record levels on July 5, with a new all-time record high air temperature of 106˚F and a record heat index of 117˚F. While this reading was warmer than some sensors in the surrounding area, it was confirmed by independent observers at the airport and verified by the National Weather Service in Raleigh.

That sizzling heat, combined with the lack of precipitation in June, also fed a flash drought as parched soils helped keep our air temperatures elevated, and those warm temperatures further stressed soil moisture levels.

That rapid drying, including the second-greatest week-to-week increase in drought coverage across our state on the US Drought Monitor, is also something we expect more of in the future as warmer temperatures increase evaporation rates and deplete soil moisture more quickly.

And at both ends of the state last year, summer droughts ended suddenly at the hands of heavy rainfall from tropical storms. Two of those storms in 2024 – PTC8 and Helene – dropped more than 18 inches of rain in parts of the state, adding to a short but growing list of such storms, of which we’ve had nine in the past 26 years.

Along with the “weather whiplash” from those abrupt dry-to-wet changes, the historically heavy rainfall from larger, slower, and more moisture-rich storms such as Helene — one of 27 billion-dollar climate disasters in the US last year — stands out as another impact we can expect more of in our future climate.

And it will long stand as an indelible memory from 2024, when flooding reached unthinkable levels and parts of western North Carolina were nearly wiped off the map.