The long-awaited arrival of El Niño late last year helped our winter start with a splash, with multiple rain events across the state in December and January. But prevailing warm weather meant no snow for most areas, with the last flakes now a distant memory from more than two years ago.

To wrap up this winter, we’ll look at the final rankings and statistics for the season and assess the predictions from our winter outlook, including about El Niño and its impacts, our precipitation patterns, and the scarcity of snowfall. We’ll also preview the evolution of ENSO to come this year, and what it could mean for us.

Winter By the Numbers

The three months from December through February, which constitute the climatological winter, were overall warm and wet in North Carolina.

Data from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) shows this was tied for our 19th-warmest winter since 1895, with an average temperature 2°F warmer than the 1990 to 2020 average.

Among local weather stations, it ranked as the 5th-warmest winter for Raleigh, the 6th-warmest in Reidsville, tied for the 8th-warmest in Wilson, and the 9th-warmest in both Hickory and Salisbury.

NCEI’s data also notes this as our 28th-wettest winter in the past 129 years, with the statewide average precipitation of 13.82 inches, or 2.67 inches above the 1991 to 2020 average.

Banner Elk recorded its 3rd-wettest winter out of 100 years with observations, measuring 18.68 inches of precipitation in total. It was also the 3rd-wettest winter for Greensboro since 1903, the 5th-wettest in Marion, and the 6th-wettest in Morganton.

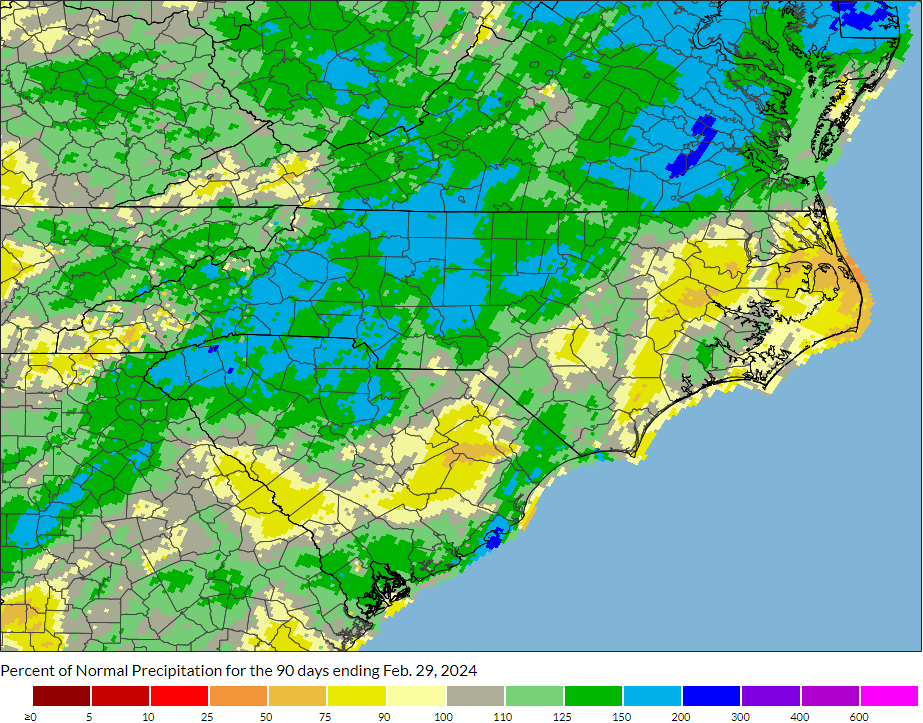

In eastern North Carolina, a drier end to the winter left some areas below their normal precipitation. Deficits ranged from just 0.27 inches in Greenville to 1.90 inches in Kinston to 3.13 inches at Hatteras, which had its 14th-driest winter in the past 67 years.

An Active El Niño

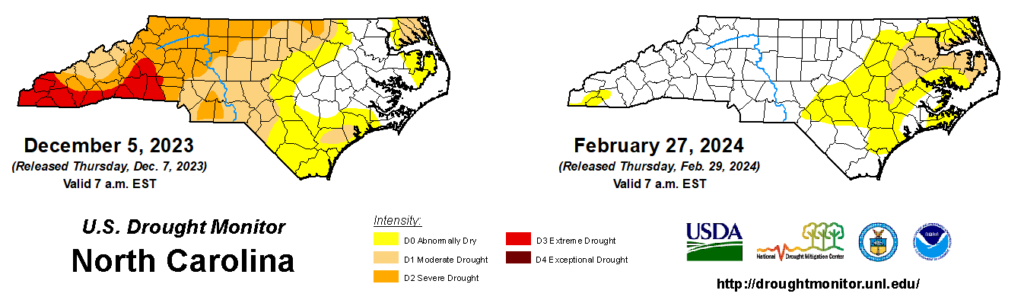

In our winter outlook, released last November, we previewed the potential impacts of El Niño, which favors wet weather in our part of the country. And at that time, it couldn’t come soon enough, given the drought conditions encompassing more than half of the state last fall.

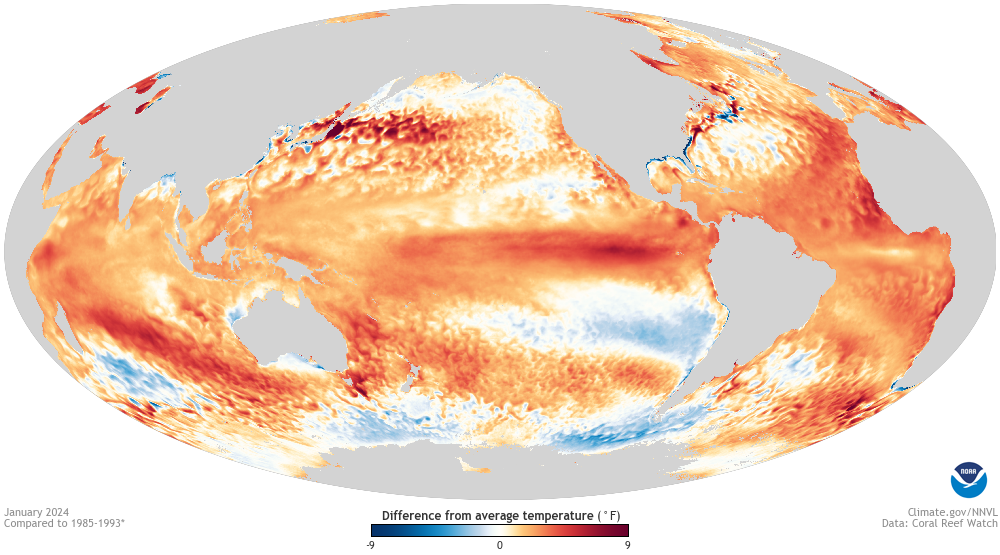

Historically, stronger El Niños have often meant stronger impacts, and we expected a relatively strong El Niño event in place this winter, with Pacific sea surface temperature anomalies peaking around 2.0°C above normal.

That was a fairly accurate prediction when compared against the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI), which showed a wintertime average anomaly of +1.8°C.

Another indicator, the Multivariate ENSO Index (MEI), showed a weaker signal all season, with a maximum anomaly of 1.1°C in November and December, decreasing to 0.7°C in December and January.

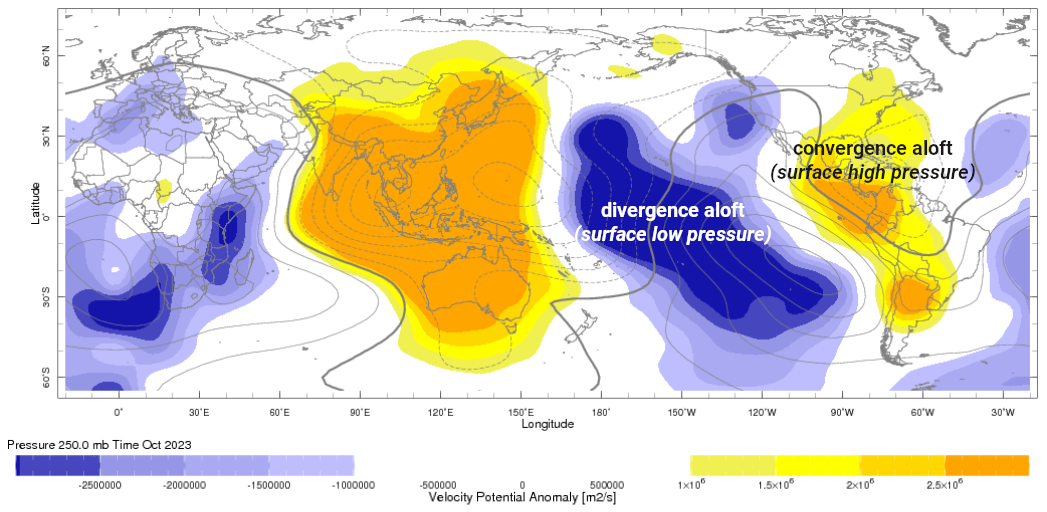

In our outlook, we noted that the MEI was also lower entering the season, and observed that it wasn’t the only indicator showing a less-developed El Niño. The circulation pattern last October featured a broad area of upper-atmospheric convergence, associated with surface high pressure, over the eastern US.

That informed another prediction – that wetter weather wouldn’t arrive immediately after the winter started.

In reality, we saw a remarkably quick pattern change early in the winter, transitioning from the weeks-long rain-free stretches in the fall to a series of heavy rain events beginning on December 10. Following our 42nd-driest November on record, December was our 7th-wettest in North Carolina.

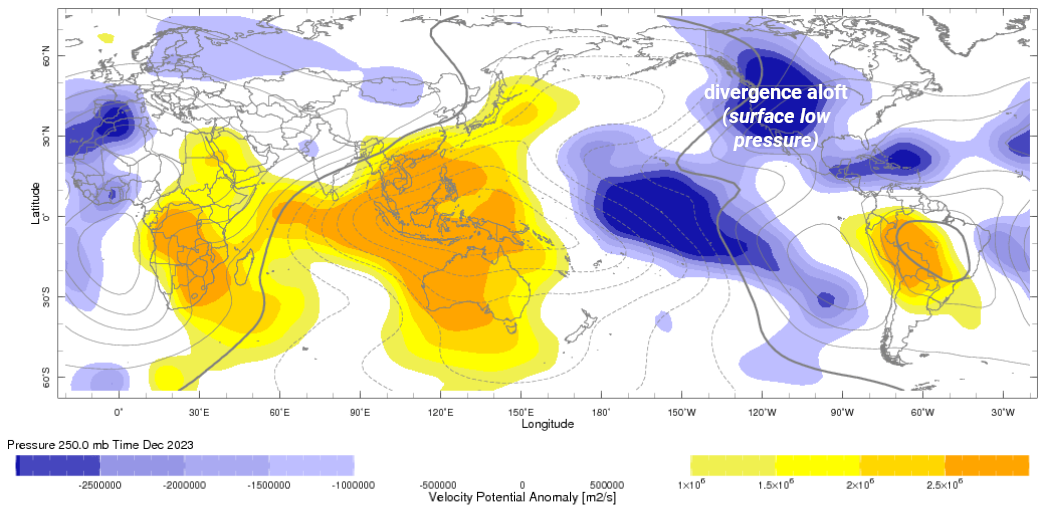

The circulation pattern also reflected that change, with upper-level divergence – and surface low pressure – across much of the continental US, and (critically) over the Gulf of Mexico, in December.

While that flew in the face of our prediction, it was also hard to be disappointed when the rains returned with regularity early in the winter.

Precipitation Patterns

Even though we anticipated a drier start to winter, we also expected wetter conditions by January or February – if not both.

The wet pattern from December did indeed carry over into January, which ranked as the 18th-wettest on record statewide. But by mid-month, parts of eastern North Carolina switched back to a drier pattern, which continued through February all across the state.

That was particularly surprising given our climatology in similar moderate to strong El Niño winters. Ten of those 12 Februarys were wetter than average, so a dry February like we had this year is a rare event.

That inadvertently helped another prediction pan out correctly – that we would not have a clear drought map by the end of the winter.

We figured that it would take an almost historically wet winter to fully recover from the Severe (D2) and Extreme (D3) Drought conditions we started the season with. But those areas in western North Carolina had just such a winter, ranked among their top five or top ten wettest on record, and all drought was gone by mid-January.

However, the dry end to the season led to the reemergence of Moderate Drought (D1) in parts of the Coastal Plain by late February, which meant there was drought on the map by the end of the season.

Snow This Season

Given recent trends in our wintertime temperatures, including warming associated with climate change, we thought an overall cool season would be a longshot this year, and instead expected near- to above-normal temperatures, on average.

It did turn out to be a warm season, with average temperatures 2 to 4 degrees above normal across the state. Our only sustained period of colder temperatures came from January 16 to 21, when nighttime lows dipped into the teens.

During the 91-day winter season, there were 55 days in Raleigh, and 56 in Charlotte, on which temperatures never dropped below freezing. That prevailing warmth ultimately doomed our snow chances this winter.

The increased frequency of storm systems tracking along our coastline has historically made El Niño winters more favorable for wintry weather, and because of that, we expected at least one measurable snowfall in most areas.

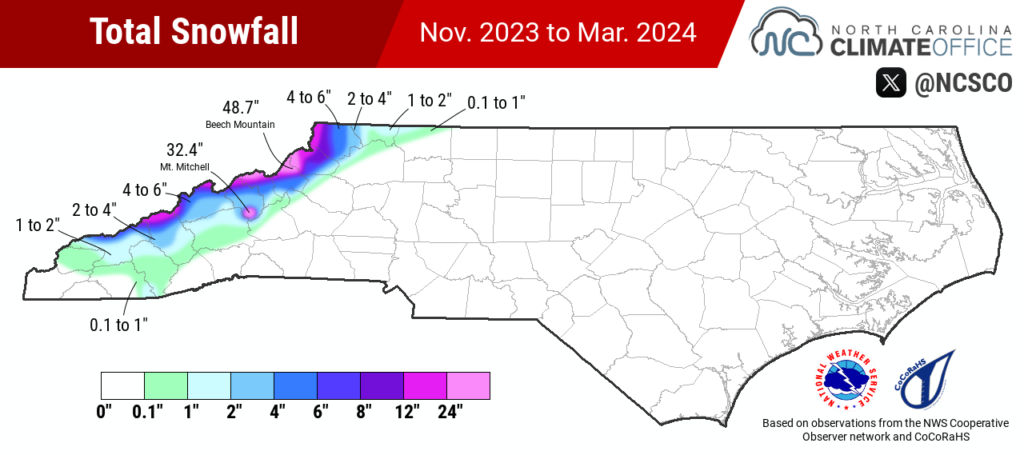

However, those precipitation events never aligned with our few cold periods, at least outside of the Mountains, which left this winter with the same fate as the last one – snow-free across most of the state.

Even our higher-elevation areas had relatively little snow this winter. Mount Mitchell had just 32.4 inches of snow – the 4th-least in a season there, or just 36% of the normal amount, and Marshall had only 7.5 inches, or less than 30% of its normal amount.

Totals were slightly higher in the northern Mountains, but even there, it was a below-average season. Beech Mountain had 48.7 inches, or 17.8 inches below normal, and Boone had 8.3 inches, compared to a normal of 25.6 inches.

Across the rest of the state, our snow-free streaks now exceed two years. Greensboro, Monroe, and Raleigh all last saw measurable snowfall on January 29, 2022, or 779 days ago.

As of this post’s publication on March 18, Charlotte’s current 779-day snow-free streak is the longest on record there, surpassing the previous 778-day streak that ended in March 1993. And Asheville has also now set a new record streak of 737 days without measurable snowfall, breaking the record set in February 2013.

What’s Next for ENSO

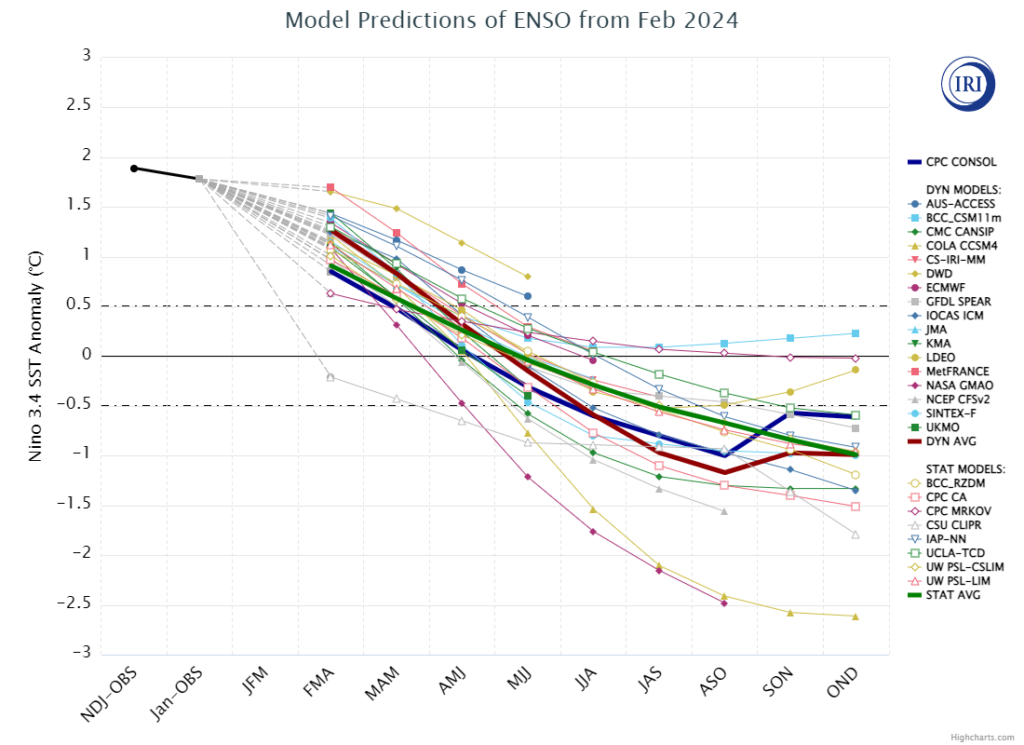

The beginning of March saw an ominous sign in sea surface temperatures across the equatorial Pacific Ocean: a small pool of cooler water just west of the Galapagos Islands.

There’s more where that came from, as a wedge of cooler water beneath the surface has continued to progress eastward and bubble up toward the surface.

It’s a good indication that this El Niño is on its way out, and in a hurry. Current model forecasts show a shift back to ENSO-neutral conditions this spring, and a majority now favor the development of a La Niña pattern later this year.

Of course, that would be a familiar feeling, as prior to the current El Niño, we endured three consecutive La Niña winters in a row. While each played out slightly differently, those were overall warm and dry winters, with only one particularly snowy month in January 2022.

Before we get to next winter, we may feel the effects of that La Niña in a decidedly unfrozen way. The weakening of upper-level trade winds in the tropics typical during those events, combined with the persistent record warm sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean, strongly favor an active hurricane season this year.

Although more storms do not guarantee more landfalls – as last year showed, with 21 tropical storms but only three affecting the continental United States – it does increase the chances of those systems or their remnants affecting us by late summer or fall.

Beyond that, the northward shift of the jet stream associated with La Niña may eventually bring a shift to a warmer and drier weather pattern later this year.

If that happens – and it’s certainly a big if, since we’re looking almost nine months into the future, and lots can happen during the often-tumultuous summers over which ENSO events take shape – then we could be staring down an unfavorable setup for snow entering next winter.

If we shake out any flakes, then it would in some ways defy the odds, given our recent winter warmth and a La Niña pattern that’s often less suited for snow chances.

And if one year from now we’re reflecting on another snow-free winter, then it will mean we’re in unprecedented, record-breaking territory across central and eastern North Carolina, with our snow drought surpassing the three-plus-year streak from the early 1990s.

Either way, the stage is already getting set, and the anticipation is building, for a momentous winter next year.