This is the third post in our “Stormy Summer” series looking back at some memorable hurricane anniversaries occurring in 2019.

Out of almost 150 years of recorded hurricanes in North Carolina through 1999, none were quite like Floyd.

When the sixth named storm of the 1999 season arrived at our coast twenty years ago today, it wasn’t the strongest to hit or the most damaging for beach towns that had already endured the wrath of Bertha, Fran, and Bonnie over the previous three years.

But Floyd’s legacy — and what made it so unique — was written in the rain it brought, the floods that ensued, and in many parts of the North Carolina Coastal Plain, in the high-water marks on homes and businesses that had never before endured such an extreme event.

Floyd wasn’t particularly unusual, meteorologically speaking. Sure, it was a strong storm, reaching Category-4 status over the warm waters east of the Bahamas. But as it turned northward between the US east coast and the fringes of the weakening Bermuda high, Floyd dropped to Category-2 strength.

It was weakened by an eyewall replacement cycle that strong storms of its ilk inevitably encounter, along with dry air to the northwest and increasing wind shear to its south.

After briefly threatening central Florida, Floyd’s northward turn was well-captured by the forecast models, which then showed it targeting the Carolina coast. But models and even most folks’ wildest imaginations could not fully capture the hazards it would ultimately bring.

Part 1: Crossing the Coast

Floyd’s eye made landfall on Bald Head Island around 5:30 am on September 16. It was holding at Category-2 strength with maximum sustained winds of 104 mph.

Winds gusted as high as 120 mph at the New Hanover County Emergency Operations Center in Wilmington, and a portable 10-meter anemometer on Topsail Beach measured sustained winds of 96 mph with gusts to 122 mph as Floyd’s center of circulation moved over the island.

The southern coastline also absorbed Floyd’s storm surge, which was reportedly as high as 15 feet at Long Beach. The wind and waves eroded sand dunes and beaches, and damaged coastal properties and piers.

Once Floyd’s eye moved over land, the storm weakened but was still a Category-1 hurricane as it passed between New Bern and Greenville. Tropical storm-force sustained winds were observed from Raleigh and Fayetteville eastward.

Those high winds were short-lived, though. Just eight hours after entering the state, the center of Floyd had already exited. With a forward speed of more than 20 mph, it was a fast-moving storm that didn’t linger like Florence or 1955’s Ione, which spun for more than a day across the Coastal Plain.

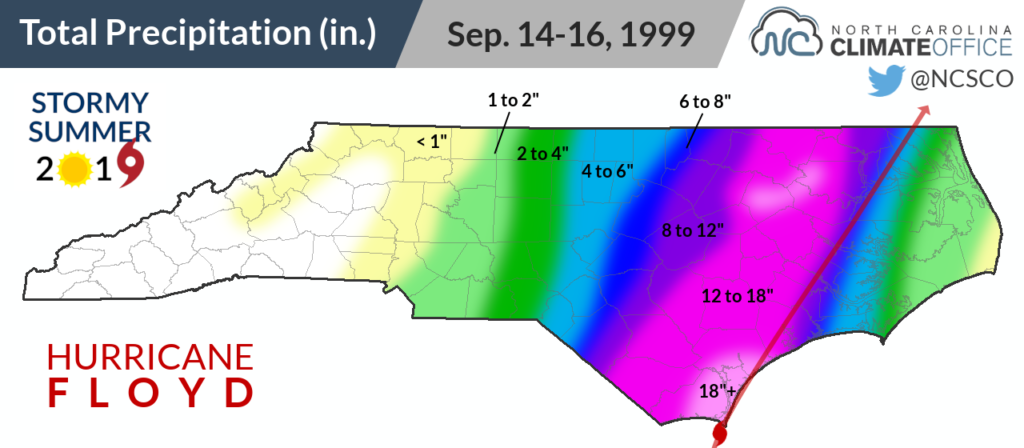

But in eastern North Carolina, the rain lasted for far more than eight hours, in some areas beginning two days before the storm made landfall.

On September 14, an inverted trough — an area of easterly flow along the remnants of a frontal boundary — was moving toward the southern coast, bringing in moist air and producing showers before Floyd even arrived.

Foreshadowing the threat, the National Weather Service in Raleigh noted in a mid-day forecast discussion that “slow-moving showers and thunderstorms are soaking already moist soils over the Coastal Plain and west into the Fayetteville and Raleigh areas… This will enhance the already high threat of flooding when the remnants of Floyd arrive.”

As Floyd closed in, it began feeding moisture along that boundary and a cold front approaching from the west. Those features helped extend the amount of time that rain was falling. In Wilmington, measurable precipitation was reported for 34 consecutive hours.

The axis of heaviest precipitation also shifted west of the eye and between the converging boundaries, which provided additional lift to support heavy rainfall.

At the Wilmington Airport, 13.38 inches of rain fell in a single day on September 15 — a local record that still stands even after Florence. On the same day, Rocky Mount received 16.55 inches, which is also the highest 24-hour total at that location.

The storm total precipitation amounted to as much as two feet. Southport totalled 24.06 inches over three days, and stretches of the Cape Fear, Neuse, Tar, and Roanoke river basins got 12 inches or more.

That began the next phase of Floyd’s impacts. Water falling from above gave way to water rising from below.

Part 2: Raging Rivers, Rising Water

Coastal rivers were already swollen after Dennis moved through just two weeks earlier, so as rain fell across their watersheds and rushed downstream, they continued rising well past record heights. When the rivers were full, the water picked the next place with a vacancy — in streets, homes, and businesses across the coast.

The Cape Fear River at Chinquapin in Duplin County rose 10 feet above its flood stage to a height of 23.51 feet. That level was only surpassed by Florence last year.

The Neuse River in Goldsboro and Kinston also hit then-record levels of 28.85 and 27.71 feet, respectively, which were not topped until Matthew hit in 2016. In Kinston, it took a full seven days to hit those crests as water worked its way down from the upper reaches of the Neuse basin.

The worst flooding came along the Tar River. In Tarboro, the river crested at 41.51 feet, a full 22 feet above its flood stage. It’s a record that still stands today, as does the height of 29.74 feet in Greenville reached on September 21, 1999.

In Tarboro, boats and helicopters rescued stranded citizens while those who could escape their homes slept in their cars in commercial parking lots. Across the river in Princeville, the damage was far worse.

The town founded by former slaves lies within the Tar’s 100-year floodplain, and the protection offered by an earthen levee was no match for Floyd’s flood. The levee broke, flooding Princeville to a height of 30 feet in some places. In the town of less than 2,500 people, 600 homes were heavily damaged or destroyed.

All across the coast, the relentless flood waters affected every aspect of peoples’ lives. Power lines were toppled or short-circuited, cutting off electricity for 1.5 million homes and businesses. Many also lost running water, and in some areas, the water supply was contaminated by sewage, fertilizer, and gasoline.

The flood water forced tens of thousands of people out of their homes, and more than 1,400 swift water rescues were conducted.

Even those trying to escape from the storm-ravaged state couldn’t get too far. Flooding closed almost 1,000 roads, including interstates 40 and 95.

Days turned into weeks turned into months after the storm passed before its full toll came to light. Even estimating the storm’s monetary damage was difficult because so few affected homeowners had flood insurance, and insured losses are the standard measuring stick for calculating total costs.

In the wake of Florence last year, the North Carolina Office of State Budget and Management cited Floyd’s damage at between $7 and $9.4 billion, adjusted for inflation. Only Florence ($22 billion as of May 2019) has surpassed Floyd among our state’s costliest hurricanes.

It also came with a cost of human life. The state medical examiner’s office blamed 52 deaths in the state on Floyd, 36 of which were due to drowning. That ranks Floyd third among our state’s deadliest storms, behind the July 1916 storm in the Mountains whose floods killed an estimated 80 people and the September 1883 hurricane responsible for 53 fatalities.

Part 3: Since the Storm

For all the damage it did, perhaps no storm in North Carolina looks more different through the lens of history than Floyd. In 1999, it was unequaled. Twenty years later, it’s clear that Floyd was the first — not the only — of its kind.

The waters have risen again in Matthew and Florence, two storms following in Floyd’s footsteps, and the cost has extended beyond just an economic one. This era of flooding hurricanes has made the folks experiencing them rethink where they live and what the future holds.

In towns like Windsor, situated on the banks of the narrow Cashie River, residents were told that the 18 inches of rain from Floyd was a 1-in-1,000 year event, and most didn’t rebuild any differently, expecting there would never be another one like it in their lifetimes.

But after Florence, Matthew, and even the remnants of Tropical Storm Nicole in 2010 flooded their towns from rainfall events quoted as 1-in-100 to 1-in-500 year frequencies, some are beginning to wonder if they’re 1,500 years old — or if these events aren’t as rare as those numbers suggest.

It’s more likely to be the latter, of course, but why?

In part, it’s because those returns intervals are only as good as the historical observations they’re based on. At weather stations such as Lewiston just up the road from Windsor, Floyd yielded two consecutive days with higher precipitation totals than the previous greatest total dating back to March 1954, when the station began reporting.

Mathematically, it was no wonder that Floyd was such an extreme event. It literally defined the tail of the precipitation distribution, at least until Matthew hit.

When these return frequencies are next updated, we’re likely to see that 18 inches of rain in three days is no longer a 1-in-1,000 year occurrence, although that won’t change the extremity of the flooding such an event can cause.

The back-to-back nature of these storms has also made their impacts more pronounced. Before Floyd, there was Dennis. Before Matthew, there was Julia. In western North Carolina, the summer of 2004 saw the remnants of three storms — Frances, Ivan, and Jeanne — all hit within a month.

| First-Hand Accounts of Floyd Along the coast and up the rivers, Floyd’s impact was felt across many locations and sectors in eastern North Carolina. Don’t miss these two examples, including personal stories from folks who endured the storm: Farmers Felt Floyd’s Full Force, Beginning in Onslow County Floyd’s Inundation Along the Tar River Spurred a Call to Action |

So why have so many storms hit North Carolina in quick succession over the past 20 years? Perhaps it’s just a bit of bad luck, aided by the uptick in tropical activity since the mid-1990s that is partially attributed to the cyclical warming of Atlantic sea surface temperatures during that time.

A warming atmosphere could be playing a role as well, since basic physics tells us warmer air increases evaporation rates, which may lead to heavier precipitation from tropical systems.

The exact contribution of each of these factors in Floyd, Matthew, Florence, and other storms is difficult to determine, though.

As in the floods themselves, the root causes ultimately mix together among the muddy water. And ever since Floyd hit 20 years ago, that water has left an indelible impression on riverside towns in eastern North Carolina.

Sources:

- Preliminary Report – Hurricane Floyd from the National Hurricane Center

- Hurricane Floyd Event Summary from the National Weather Service in Raleigh

- Hurricane Floyd Storm Summary from the National Weather Service in Newport/Morehead City

- Hurricane Floyd, 1999 from East Carolina University’s Storms to Life

- Hurricane Floyd Floods of September 1999 from the US Department of Commerce and NOAA

- Preventing Disasters through Hazard Mitigation from Anna K. Schwab, Popular Government spring 2000 issue

- Tropical Cyclone Report – Hurricane Florence from the National Hurricane Center