This post is part of our year-long series about North Carolina’s weather extremes.

In September, our NC Extremes post highlighted the strongest hurricanes to affect North Carolina based on the pressure, wind speeds, and storm surge statistics. But when it comes to storm damage, strength isn’t always in the numbers.

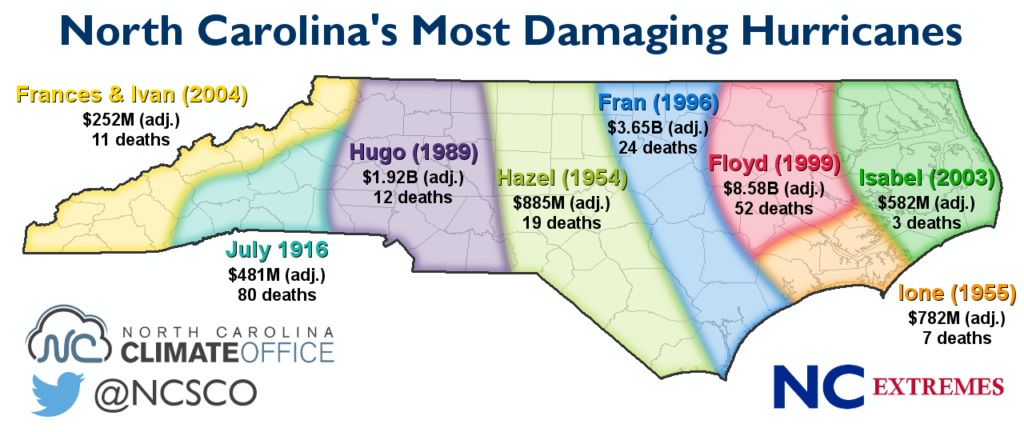

All corners of our state have seen destruction and death from tropical systems of varying intensities, whether it was because of flooding, winds, or other hazards. Accounting for all of these impacts, this post looks at some of the most damaging storms to affect various parts of North Carolina since modern record-keeping began in 1851.

It’s worth noting that this is not a comprehensive list of our damaging hurricanes, and it serves to highlight some of the most widespread, costliest, and deadliest storms across the state. As with any weather event, local impacts vary with each storm.

The map below shows some of most damaging historical hurricanes across the state. Summaries of those storms follows below.

Top 10 Costliest and Deadliest Hurricanes (as of 2015)

| Rank | Storm | Cost (2015 dollars) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Floyd (1999) | $8.58B |

| 2. | Fran (1996) | $3.65B |

| 3. | Hugo (1989) | $1.92B |

| 4. | Irene (2011) | $1.26B |

| 5. | Hazel (1954) | $885M |

| 6. | Ione (1955) | $782M |

| 7. | Connie/Diane (1955) | $711M |

| 8. | Bonnie (1998) | $588M |

| 9. | Isabel (2003) | $582M |

| 10. | July 1916 | $481M |

| Rank | Storm | Fatalities |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | July 1916 | ~80 |

| 2. | September 1883 | 53 |

| 3. | Floyd (1999) | 52 |

| 4. | “Great Beaufort” (1879) | ~40 |

| 5. | Fran (1996) | 24 |

| 6. | “San Ciriaco” (1899) | 20 to 25 |

| 7. | “Outer Banks” (1933) | 21 |

| 8. | Hazel (1954) | 19 |

| 9. | Hugo (1989) | 12 |

| 10. | Frances/Ivan (2004) | 11 |

July 1916 Hurricane

The most damaging hurricane for parts of the mountains is one we’ve already profiled in our NC Extremes series for its record-setting precipitation. In July 1916, a landfalling Category-2 hurricane near Charleston took an inland path toward the Appalachians.

The storm’s northwesterly track and counterclockwise wind field helped air rise up the mountain slopes and produce more than a foot of rain. Altapass recorded 22.22 inches in just 24 hours.

The rain fell on already wet ground after another tropical system moved through a few weeks earlier, so the Swannanoa, French Broad, and Catawba rivers rose to record levels. Flooding wiped out bridges, homes, and farmland along the rivers, causing $22 million in damage — about half of which came from crop losses — which translates into $481 million in today’s dollars.

With an estimated 80 people killed during the floods, mostly due to drowning and the collapse of the Southern Railway bridge in Belmont, this is North Carolina’s deadliest tropical system in modern history.

Hurricanes Frances and Ivan (2004)

In 2004, the mountains received another tropical one-two punch from the remnants of hurricanes Frances and Ivan. Much of the region received more than 8 inches of rain from Frances, which was enough to fill rivers and flood parts of Asheville and Biltmore Village.

Just nine days later, the remnants of Hurricane Ivan followed a similar track across western North Carolina. Precipitation totals weren’t quite as high, generally between 4 and 8 inches, but on top of the rains from Frances, it was too much for some rivers and slopes to handle.

Hundreds of landslides occurred, with the worst coming near Highlands in Peeks Creek where a debris flow destroyed more than a dozen homes and killed five people. Flooding, fallen trees, and landslides also closed several roads, including Interstate 40.

Combined, Frances and Ivan caused 11 deaths in North Carolina and approximately $252 million in damage, adjusted for inflation.

Hurricane Hugo (1989)

For the western Piedmont, one hurricane stands unequalled in terms of its strength and destruction. In 1989, Hugo made landfall near Charleston, South Carolina, at Category-4 strength. The storm weakened as it moved inland, but in Charlotte and Hickory, it still brought hurricane-force wind gusts exceeding 80 mph.

In Charlotte, the intense winds toppled an estimated 80,000 trees, also knocking out windows and knocking down power lines. Some residents were without electricity for up to two weeks.

Similar wind damage was observed across the rest of the Piedmont and Foothills, with an estimated 68,000 acres of forests destroyed and an additional 2.7 million acres damaged.

Altogether, Hugo’s damage in North Carolina amounted to about $1 billion — $1.92 billion, adjusted for inflation — and as many as 12 deaths.

Hurricane Hazel (1954)

As our only known landfalling Category 4 storm, Hurricane Hazel from 1954 is one of North Carolina’s strongest hurricanes, and it’s also one of the most damaging. The storm’s extreme winds and surge of up to 18 feet leveled nearly every structure between Cape Fear and the South Carolina border.

But the damage didn’t end at the coastline. Like Hugo, Hazel remained a strong storm as it trekked inland. Fayetteville reported wind gusts of up to 110 mph, and Raleigh had gusts of 90 mph along with hurricane-force sustained winds. Hazel’s forward speed of nearly 60 mph exacerbated the powerful punch of its winds.

Although it was a fast-moving storm, Hazel brought heavy rainfall across the Piedmont. Precipitation totals exceeding 7 inches were observed from the Sandhills to the Virginia border. The wet ground plus high winds meant downed trees, and in Raleigh, it was said that two to three trees per block fell during the storm.

Hazel resulted in 19 deaths — mostly along the coast — and destroyed about 15,000 homes. Its total damage was $100 million, or $885 million today.

Hurricane Fran (1996)

Following Hazel, the next major hurricane to make landfall in North Carolina was Fran in 1996. Packing Category-3 strength winds of 115 mph, Fran came ashore near Cape Fear on the evening of September 5.

The southern coast was devastated by Fran’s high winds and storm surge, which peaked at 12 feet in North Topsail Beach. Hundreds of homes and several piers along the coast were damaged or destroyed, and an estimated 75% of homes in Wilmington sustained damage from the storm.

Fran remained at hurricane strength as it moved inland. Fayetteville and Raleigh each reported wind gusts of up to 79 mph, and a 100-mph gust was measured in Greenville. Wind damage and power outages were widespread, particularly across the Triangle. Rainfall exceeding 7 inches also caused flooding along the Cape Fear River and Crabtree Creek in Raleigh.

Fran caused an estimated $2.4 billion in damage in 1996 dollars, or about $3.65 billion today. Of the former total, about $700 million came to the agriculture industry and about $900 million came in Wake County alone. Fran is blamed for 24 deaths across the state.

Hurricane Floyd (1999)

Just three years after Fran, another destructive storm struck eastern North Carolina with much costlier and deadlier results. Like Fran, Hurricane Floyd made landfall near Cape Fear, but at Category-2 strength. Floyd still took a damaging toll on the coastline, inundating the southern coast with a storm surge of up to 15 feet.

As Floyd continued to move inland, it was a huge rainmaker for eastern North Carolina, with more than 12 inches of rain falling across the Coastal Plain. Just 11 days earlier, rains from Hurricane Dennis saturated that region, so the additional precipitation from Floyd pushed the Tar and Neuse rivers to record levels.

Rivers and streams overflowed their banks and levees, flooding nearby towns including Rocky Mount, Tarboro, Greenville, and Washington. FEMA said that statewide, 56,000 homes were damaged, 17,000 were uninhabitable, and 7,300 were destroyed entirely. In addition, it was reported that 300 bridges were damaged or destroyed and 40 dams failed. The agriculture industry was also devastated, losing crops, livestock, and jobs due to the flooding.

With a total damage bill estimated at $6 billion, or about $8.58 billion in today’s dollars, Floyd is North Carolina’s costliest hurricane. The 52 deaths noted by the state medical examiner also make it one of the deadliest.

All in all, Floyd is perhaps the most comprehensively destructive storm ever for eastern North Carolina. H. David Bruton, the state’s then-Secretary of Health and Human Services, remarked that “nothing since the Civil War has been as destructive to families here.”

Hurricane Ione (1955)

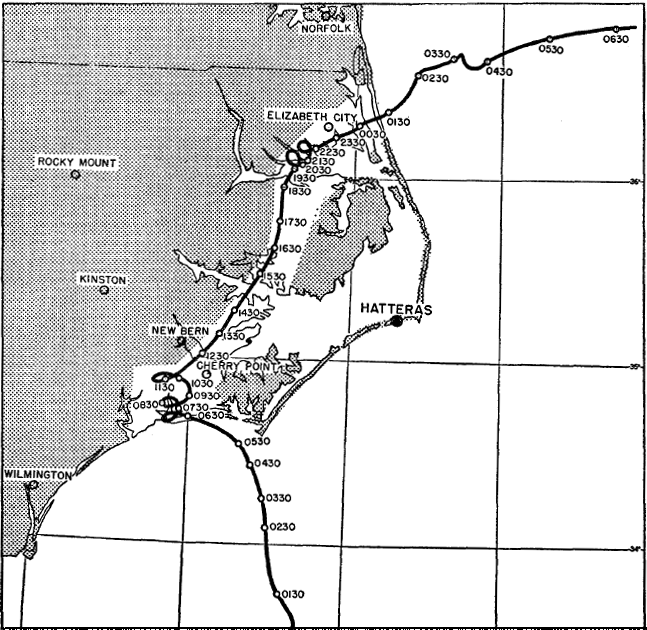

The summer of 1955 was a busy one for the coast of North Carolina. In mid-August, Hurricane Connie made landfall near Morehead City as a Category-2 storm. Just five days later, Wilmington was hit by Tropical Storm Diane. And only a month after that, Hurricane Ione came ashore, like Connie, as a Category 2 near Morehead City.

Flooding from Connie and Diane had barely subsided by the time Ione arrived. And once Ione got to the Crystal Coast, it was in no hurry to move on, lingering over the eastern part of the state for nearly two full days as it danced across the coast.

As a result, more than 10 inches of rain fell in Jacksonville, New Bern, and Morehead City. Still filled with the rain from the August storms, local rivers crested and flooded the towns, with water observed to a depth of 6 feet or more in New Bern. Highways from Sneads Ferry to Kinston to Washington were washed out by the flood waters.

An estimated 90,000 acres of farmland was also flooded, resulting in about $46 million in crop damage. Ione’s total damage in North Carolina was $88 million, equal to about $782 million today. Primarily due to drowning, 7 people died in North Carolina due to Ione.

Hurricane Isabel (2003)

Jutting out into the Atlantic and the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, North Carolina’s Outer Banks can be an easy target for hurricanes skirting the coast. But one of the most damaging events for that region came from a direct hit by Hurricane Isabel in 2003.

Although Isabel weakened from Category-4 strength just 36 hours before reaching the coast, it still made landfall as a strong Category-2 storm north of Cape Lookout. The Outer Banks including Ocracoke, Hatteras, and points north were hit with hurricane-force winds. Even Plymouth — more than 50 miles inland — reported gusts as high as 95 mph.

The immediate coast was also subjected to a storm surge of 6 to 8 feet. South of Frisco on Hatteras Island, the storm knocked out Highway 12 and created a nearly half-mile-wide inlet, isolating Hatteras Village residents for two months. Isabel also funneled water up the Pamlico and Neuse rivers, flooding low-lying towns like Oriental.

In North Carolina, 3 deaths were reported due to Isabel with damages of $450 million — adjusted for inflation, more than $582 million.

Other Notable Storms

The Great Beaufort Hurricane of 1879 — which we noted in the last NC Extremes post for its high wind speeds at landfall — caused 46 deaths in North Carolina and Virginia. Four years later, the September 1883 hurricane brought hurricane-force winds to Smithville — now known as Southport — and intense flooding up the Cape Fear River. All told, the storm caused 53 deaths in North Carolina.

Like Isabel, the September 1913 hurricane funneled water up the coastal rivers and caused locally heavy flooding in Washington. We profiled this storm in more detail in our Century Since the Storm blog post series.

Besides the 1955 trio of Connie, Diane, and Ione, several other storms have had damaging effects on the central coast. The 1933 Outer Banks hurricane brushed the coast but still caused intense winds, flooding, and 21 deaths. In 1960, Hurricane Donna left a path of destruction along the entire U.S. east coast, with high winds, beach erosion, and buildings destroyed in North Carolina. And in 2011, Hurricane Irene was just a Category 1 at landfall near Morehead City, but it still caused an estimated $1.2 billion in total damage.

Although our two posts on North Carolina’s strong and damaging hurricanes can only cover a fraction of the storms that have affected our state, the storms we have covered help tell a familiar story of a state where extreme hurricanes are part of our climate and their impacts are a part of our history.