This is the fourth post in our “Stormy Summer” series looking back at some memorable hurricane anniversaries occurring in 2019.

Well inland from the tempest-tossed coastline, one part of North Carolina would seem to be a safe haven from the hazards of hurricanes.

The western Piedmont is at least a three-hour drive from the closest beach. In addition, the local terrain typically isn’t extreme enough to induce the same rising-air-fueled deluges or landslides that the Mountains see from the remnants of tropical storms.

But the corridor from Charlotte through Greensboro isn’t immune from tropical storms, either. Long-time residents remember witnessing, or at least hearing parents and grandparents share the stories from Hurricane Hazel in 1954.

On its way inland from landfalling at Category-4 strength, Hazel still had plenty of power as it crossed the Piedmont. The storm damaged 39,000 homes and destroyed 15,000 in North Carolina, and tropical storm-force sustained winds as far west as Greensboro knocked down trees across the state.

After Hazel, the period of quiet in the tropical Atlantic during the 1960s, ’70s, and early ’80s surely left some wondering when the next storm like it — one whose effects were felt far from the coast — would hit.

In late September 1989, they got their answer.

Hugo Hits the Coast

In some storms, strength is secondary to the overall impacts. Floyd, for instance, is remembered far more for its inland flooding than for the lashing its Category-2 winds gave to the southern coast.

Hurricane Hugo, on the other hand, was defined by its strength, and it was a monster.

On satellite imagery, it had a threatening look as it approached the South Carolina coast, from its 30-mile wide circular eye to its outer bands, which sprawled westward like an outstretched arm — the product of tropical moisture on Hugo’s fringes interacting with an upper-level low pressure system over the deep south.

That upper-level low, along with high pressure off the mid-Atlantic coast, acted like a baseball pitching machine, propelling Hugo forward at speeds of more than 20 mph.

Even worse, as it barreled full speed ahead toward the South Carolina coast, it was gaining strength. By mid-day on September 21, Hugo reached Category-4 status with maximum sustained winds of 138 mph.

It would hold that strength until it made landfall just northeast of Charleston around midnight on Friday, September 22. Hugo remains the most recent of South Carolina’s three landfalling Category-4 hurricanes, after Hazel and 1959’s Gracie.

Hugo’s impacts in South Carolina are well-documented in a recently released story map by the state’s Department of Natural Resources, including never-before-published images of the storm’s damage.

Even more than 100 miles from the point of landfall, North Carolina’s southern coastline still felt the effects of such a strong storm.

A number of homes and piers were damaged at beaches in Brunswick, New Hanover, and Pender counties. Sand dunes offered some protection, but many were destroyed by Hugo’s surge, which reached 9 feet above sea level at Ocean Isle Beach and Sunset Beach.

Impacts Inland

Hugo’s biggest hit in our state came in the overnight hours that followed. Tropical systems inevitably weaken after moving over land, deprived of the warm water that fuels their intensity while their winds are blunted by the friction of the earth’s surface.

But strong storms like Hazel and Hugo can still pack a punch hundreds of miles inland.

Six hours after it made landfall, the center of Hugo passed just west of Charlotte, and it was still producing hurricane-force wind gusts.

Until the mid-1990s, the National Weather Service had a number of satellite offices tasked with issuing warnings for smaller county areas. Charlotte hosted one of those offices at Douglas International Airport, and during Hugo, its 20-foot anemometer measured a gust of up to 87 mph at 5:20 am as Hugo’s center roared through.

The FAA control tower at the airport, which was evacuated during the height of the storm, measured a gust of 99 mph.

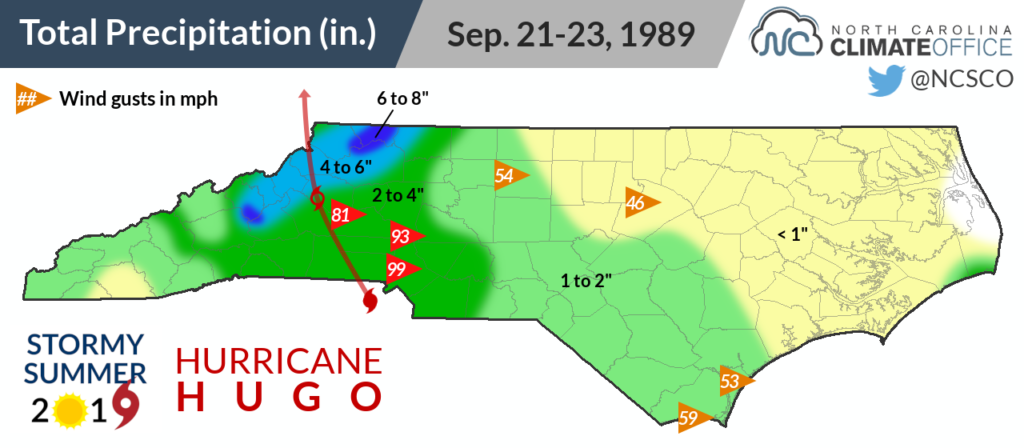

As Hugo continued racing northward, it was downgraded to a tropical storm, but it was still dangerous with strong wind gusts. Across a 50-mile swath from Charlotte through Mount Airy — just east of where the decaying eye tracked and where the storm’s forward motion added to its punch — the wind damage was severe.

Wind gusts of 81 mph were measured when the storm reached Hickory. Glass windows in Charlotte’s skyscrapers shattered. Boats were tossed like toys on Lake Norman. Tens of thousands of trees were flattened.

Power was knocked out for weeks in some spots. Duke Power and Progress Energy reported a combined 876,000 power outages across North and South Carolina during the storm.

Because of Hugo’s fast movement, which approached 30 mph as it scurried out of the northern Mountains, precipitation totals were generally less than four inches. That likely prevented even more widespread downed trees and power lines.

Moist air moving up the mountain slopes did produce some higher totals, including 8.35 inches on Mount Mitchell, which caused flash flooding in streams and on some roads in the northern Mountains.

While Hugo was not responsible for any tornadoes in North Carolina, the damage looked as though one had moved through. And the western Piedmont was familiar with that sort of damage. Just four months earlier on May 5, a line of severe thunderstorms produced 11 tornadoes from the Foothills through the Triangle.

In Catawba County, the damage from Hugo was said to be worse than that of the EF-4 that rolled through on May 5.

The National Weather Service said Mecklenburg County “looks like a war zone”. Other counties were unreachable in the hours after the storm since electrical and phone lines were knocked out.

Between 7 and 12 deaths in the state were at least indirectly blamed on the storm. Among them, a sleeping 6-month old child in Union County was killed when a tree fell on his home. Elsewhere in the county, a motorcycle rider and his bike were found lying in a field. With no tire tracks leading from the road, officials suspected the storm’s winds picked him up and threw him off the highway.

| For more on Hugo’s damage around Charlotte and how Duke Energy learned from the storm, be sure to check out our collection of stories from Duke employees: For Duke Energy, No Shelter from Hugo’s Storm |

Still Standing Out

There’s a reason why pretty much anyone who spent the late ’80s in the western Piedmont will tell you Hugo is bar-none the worst hurricane they’ve ever been through. It was the strongest storm to hit Charlotte since the 1893 Sea Islands Hurricane.

At the time it hit, Hugo was the costliest hurricane in US history, and it was North Carolina’s first billion-dollar storm. Adjusted for inflation, its damage total is more like $2 billion today, which still ranks it fifth among our state’s costliest storms behind Florence ($17 billion), Floyd ($9.4 billion), Matthew ($4.8 billion), and Fran ($3.9 billion).

Among storms since 1989, only one has whipped up winds and toppled trees in remotely the same way Hugo did across the western Piedmont.

Last year as Hurricane Michael made its way inland from a Category-5 hit along Florida’s Gulf coast, its remnants were still at tropical storm-strength as they crossed the North Carolina Piedmont.

Duke Energy reported more than 670,000 power outages in the Carolinas, coming up only marginally short of Hugo’s total. However, Michael caused a comparatively lower $22 million in damage based on preliminary estimates.

While its damage wasn’t as severe as Hugo’s, Michael was reminder to the western Piedmont not to get lulled into a false sense of security during hurricane season.

If you need any proof, just listen to the whispering pine trees and storm-scarred oaks across the region. They can all tell you that many years of steady growth can be quickly reversed by one rare but roaring hurricane.

Special thanks to Melissa Griffin from the South Carolina State Climatology Office and Chris Hamrick from Duke Energy for providing information and images for this post.

Sources:

- Preliminary Report – Hurricane Hugo from the National Hurricane Center

- September 1989 Special Weather Summer from Climatological Data North Carolina

- Hurricane Hugo from the National Weather Service in Wilmington

- Natural Disaster Survey Report, Hurricane Hugo from the US Department of Commerce

- Severe Weather Statement from the National Weather Service in Charlotte

- North Carolina Receives Federal Disaster Declaration for Tropical Storm Michael from the North Carolina Office of the Governor

- Central NC, including Mecklenburg, hit hard by Michael outages, Duke Energy says from the Charlotte Business Journal