It was a storm that briefly appeared set to threaten all of North Carolina’s records for landfalling hurricane intensity. In the end, Florence was weaker but wetter than initially expected, and between the storm surge, extreme rainfall, and unprecedented inland flooding, the stubborn storm still left a record-breaking mark on our state.

Storm History

Florence was the sixth named storm to form in an initially quiet start to the 2018 hurricane season. Cool water across the eastern Atlantic and strong wind shear over the Caribbean Sea inhibited storm development from June through August.

The onset of the climatologically most active month in the tropics brought increasing and above-normal sea surface temperatures off the US east coast, and a surge of five storms developing in a two-week period. Florence was the first of those, becoming a tropical depression just after it emerged off the African coast on August 31.

As Florence rapidly strengthened from a Category 1 to a Category 4 in just 24 hours beginning on September 4, it was also drifting to the north into an area of higher wind shear, which ripped the storm apart just as quickly and brought it back down to tropical storm status.

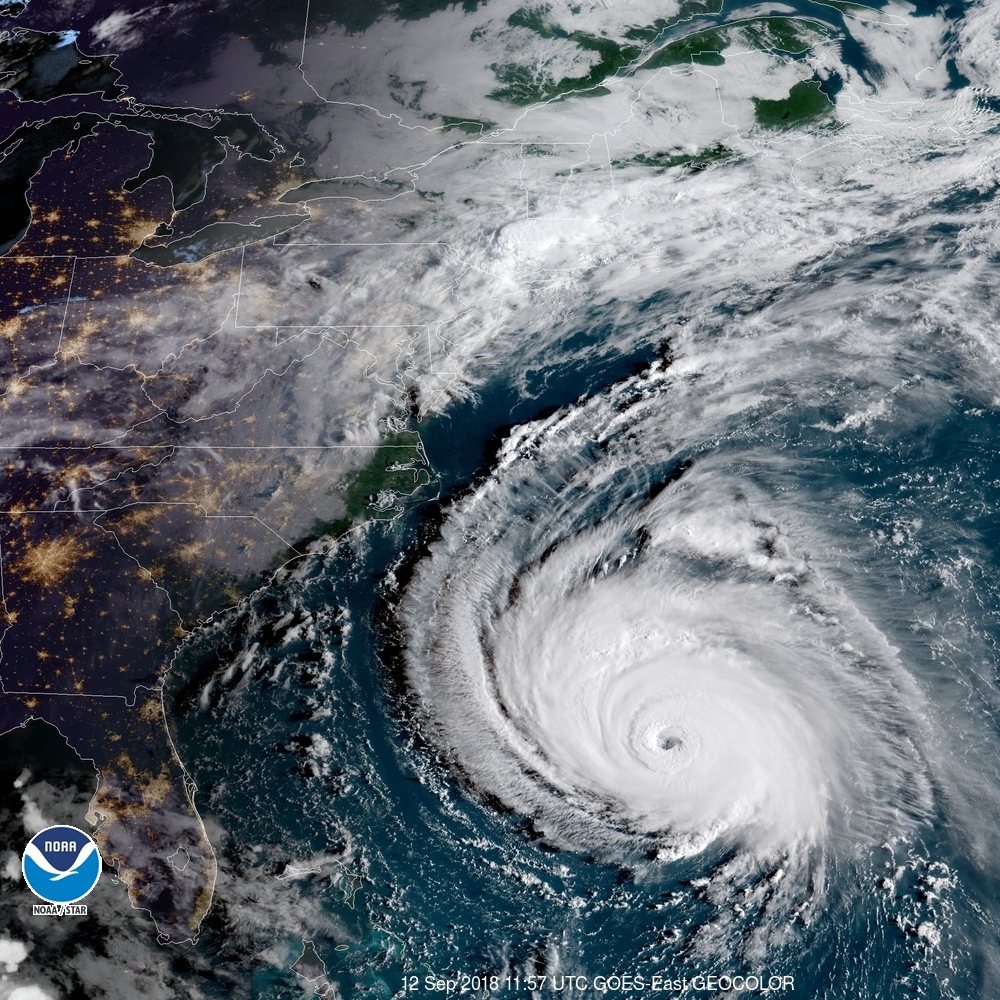

Forecasts models wrestled with whether Florence would turn north, following a weakness in an upper-level ridge, or continue its track toward the US east coast. Once it became clear that the storm would target the Carolinas, Florence became better organized, restrengthening into a Category-4 monster with maximum sustained wind speeds peaking at 138 mph.

If it maintained that intensity, Florence would have rivaled Hurricane Hazel as North Carolina’s strongest landfalling storm on record. It also achieved such strength unusually far north. Florence was well outside the so-called Hebert boxes we defined for North Carolina that show the typical trajectories of landfalling storms.

In fact, only one of North Carolina’s other 33 recorded landfalling hurricanes — the 1933 Chesapeake-Potomac hurricane — was farther north than Florence as it crossed 65°W, or the same longitude as Bermuda.

Both in terms of its latitude and its intensity, Florence was perhaps most similar to Hurricane Isabel from 2003. Both reached major hurricane status — Isabel was briefly a Category 5 — over the warm central Atlantic, several hundred miles north of the Caribbean islands.

Also like Isabel, Florence weakened and never fully recovered after it underwent an eyewall replacement cycle. As it neared the Carolina coast, the storm’s eye filled with clouds and it encountered wind shear and dry air to the southwest.

Florence was only at Category-1 strength when it made landfall around 7:15 am on Friday, September 14. Maximum sustained winds were reported at 90 mph with a minimum pressure of 958 millibars — a value that could be seen from the USGS sensors on Wrightsville Beach as the center of the storm passed over.

High Winds and Storm Surge

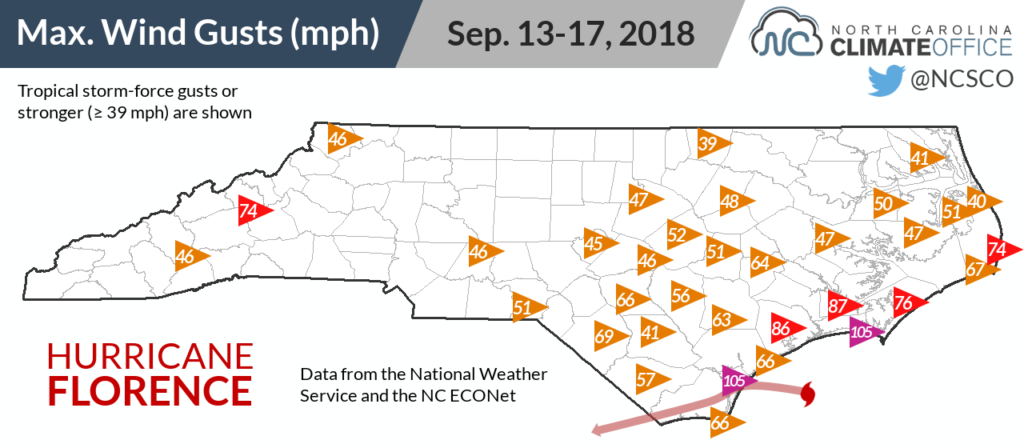

In the minutes before Florence’s eye made landfall, the Wilmington Airport reported a wind gust of 105 mph. That was the strongest gust at that site since Hurricane Helene grazed the coast 60 years ago with 135-mph winds.

Hurricane-force wind gusts were felt up and down the southern coastline, including another 105-mph gust at a weather station on Fort Macon in Carteret County, an 87-mph gust at the Cherry Point Marine Corps Air Station, and an 86-mph gust at the Jacksonville Airport.

The storm’s large diameter meant tropical storm-force winds were felt nearly 150 miles from the center, as far north as Warrenton. Among our ECONet, 21 stations — exactly half of our network — experienced wind gusts of 40 mph or greater.

Windy weather and wet ground were enough to knock down trees and power lines across the state. On Saturday morning, NC Emergency Management reported more than 800,000 outages across the state.

Even after Florence was downgraded to a tropical depression on Sunday, strong thunderstorm cells embedded within its rain bands presented hazards such as isolated tornadoes. The National Weather Service in Raleigh received four preliminary tornado reports early on Monday morning.

Along the coast, the strong winds helped drive a wall of water on shore. In New Bern, a USGS gauge reported a storm surge of 10.41 feet along the Trent River, resulting in the need for hundreds of water rescues after the city was inundated.

A surge of 6 to 8 feet was recorded along much of the southern coast, including 7.23 feet in Jacksonville, 6.63 feet at Wrightsville Beach, and 6.32 feet at Emerald Isle.

In Beaufort, the storm tide of 3.75 feet (1.142 meters) above the mean higher high water level — a reference point for where inundation usually begins — set a new record for that site, beating the previous high value of 3.39 feet (1.033 meters) from Hurricane Hazel in 1954 and Hurricane Ione in 1955.

That was one of many new high-water marks set by Florence.

Rainfall and Flooding

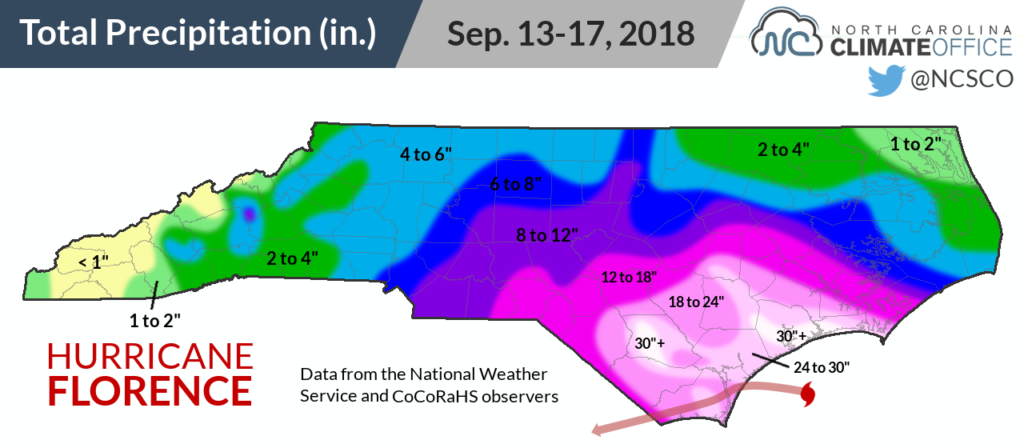

As a stark contrast to many of our other hurricanes that quickly move through the state after making landfall, Florence slowed down to a crawl. Upper-level high pressure systems surrounded the storm on three sides, and with nothing in the atmosphere to steer the storm, it moved westward at a mere walking pace over the weekend.

That made rainfall and inland flooding the greatest threat from Florence, especially across the southern coast. A moisture-rich onshore flow allowed for several days of heavy rainfall that shattered the state record for rainfall from a tropical system of 24.06 inches, which was set over a four-day period in Southport during Hurricane Floyd in 1999.

At least 13 observing stations have exceeded that amount with their accumulations from Florence. The highest reported total was 35.93 inches from a CoCoRaHS observer northwest of Elizabethtown in Bladen County. That storm total accumulation is preliminary but will likely be reviewed as a potential new state record for rain during a tropical storm.

Two additional reports of more than 30 inches came in from Onslow County. Just north of Swansboro, a CoCoRaHS observer reported 34.00 inches over a five-day period, including 16.33 inches on Saturday alone. On the western side of the county in Gurganus, a CoCoRaHS reporter received 30.38 inches of rain.

Other extreme totals included 25.58 inches at the Newport/Morehead City National Weather Service office and 23.42 inches at our ECONet station in Whiteville. Two of our stations also reported their wettest single days ever. On Sunday, Mount Mitchell picked up 14.06 inches on Sunday while Lilesville received 12.48 inches.

Despite the recently emerged Moderate Drought and Abnormally Dry conditions across the southern part of the state, most of North Carolina didn’t exactly need the rainfall from Florence.

Prior to the storm, Hatteras and Wilmington were already on pace for their wettest years on record, as well as Marion and Mount Mitchell in the western part of the state. The 23.05 inches of rain from Florence at the Wilmington Airport bumped up its year-to-date total precipitation to 86.25 inches. That site has already set a new record for annual accumulation, besting the 83.65 inches in 1877, and there are still more than three months left in the year!

| Station | County | Network | Total Accumulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elizabethtown 6.2 NW | Bladen | CoCoRaHS | 35.93 inches |

| Swansboro 1.4 N | Onslow | CoCoRaHS | 34.00 inches |

| Gurganis 0.5 N | Onslow | CoCoRaHS | 30.38 inches |

| Hofmann Forest | Onslow | RAWS | 29.64 inches |

| Hampstead 4.1 WNW | Pender | CoCoRaHS | 29.52 inches |

| Nature Conservancy | Brunswick | RAWS | 27.92 inches |

| Sunny Point | Brunswick | RAWS | 27.48 inches |

| Oak Island 0.9 ENE | Brunswick | CoCoRaHS | 26.98 inches |

| Wilmington 7.3 NE | New Hanover | CoCoRaHS | 26.58 inches |

| Whiteville 6.1 NW | Columbus | CoCoRaHS | 25.91 inches |

| Newport/Morehead City | Carteret | COOP | 25.62 inches |

| Jacksonville 1.0 NW | Onslow | CoCoRaHS | 25.28 inches |

| Mount Olive 0.4 NW | Wayne | CoCoRaHS | 25.04 inches |

With mostly saturated ground ahead of the storm, Florence’s rains had little place to go but running off into rivers, streams, and in some cases like in Durham and Chapel Hill on Monday morning, into city streets.

Some rivers along the coast already crested at new record levels, exceeding the levels seen after Hurricane Matthew in 2016 and Floyd in 1999 — the state’s previous two record-setting tropical flooding events.

The Cape Fear River in Wilmington hit a crest of 8.28 feet on Friday afternoon and the Cape Fear near Chinquapin hit 24.21 feet on Sunday, at which point the gauge was underwater and therefore unable to measure the true height of the flood waters.

The Trent River — a tributary of the Neuse — also hit a record level of 29.25 feet at the Trenton gauge. The Lumber River in Lumberton (22.21 feet) and the Little River at Manchester (35.95 feet and rising) also set new records, topping the values set by Matthew.

A Storm for the Records

Although its extreme impacts — in some cases, never before seen in North Carolina — were difficult to prepare for, Florence was relatively well forecasted, especially given the upper-level pattern it encountered as it arrived along the coast.

The National Hurricane Center’s track forecast was highly accurate five days before landfall. While intensity forecasting remains a challenge for both computer and human forecasters, Florence’s second stage of rapid intensification was agreed upon by most sources.

The potential and magnitude of such heavy, record-setting rainfall was also apparent several days ahead of time, along with the likelihood of catastrophic flooding.

That flood risk isn’t over yet. As of this post’s publication on September 18, some river levels continue to rise, the damage assessment is only beginning, and sadly, the death toll has continued to climb. The NC Division of Public Safety has confirmed 25 fatalities in North Carolina as a result of Florence, with causes ranging from fallen trees to electrocution to being carried away by flood waters.

That number puts Florence among our state’s ten deadliest tropical storms, and when all is said and done, it’s almost certain to rank among our costliest as well. (Since 2015, Matthew joined both of those lists with 26 deaths and $4.8 billion in damage in North Carolina.)

While Florence won’t be widely remembered for its intensity, few of our worst storms are. Instead, it’s hurricanes like Floyd and Matthew, and even tropical storms like the one in July 1916, that have taken the biggest toll on our state, mainly due to relentless rains over already-wet ground and the flooding that ensued.

Ask anyone in Princeville, Lumberton, and now cities like New Bern, and they’ll certainly confirm that it’s water — not wind — that leaves the most indelible mark long after the storm has gone.