This is the final post in our “Stormy Summer” series looking back at some memorable hurricane anniversaries occurring in 2019.

No discussion about North Carolina’s significant historical hurricanes is complete without including Hazel, which hit the state 65 years ago today.

In terms of intensity, Hazel is in a league of its own. Despite our recent stormy era in which we’ve been hit by storms such as Floyd, Isabel, and Florence — each of which reached Category-4 strength or greater at some point in their lives — Hazel remains North Carolina’s only known storm to make landfall as a Category-4.

So what made Hazel so damaging? Could an even stronger storm hit our state? And if it did, would that be a worst-case scenario?

As we wrap up our Stormy Summer series, we’ll look back at the history of Hazel and how it fits in among our state’s strongest hurricanes in the past, present, and future.

Remembering Hazel

Hazel developed in an environment remarkably similar to the one we’ve had over the past month this year. October 1954 started with record-setting high temperatures reaching up to 102°F in Albemarle on October 6.

At the time, the southeastern US was under the control of a strong ridge in the jet stream, and the state had slipped into drought after four consecutive hot, dry months.

It initially appeared that ridge might block Hazel’s northward progress out of the Caribbean, but an approaching trough helped push the upper-level high pressure system out to sea and provided an alley for Hazel to speed through en route to our southern coast.

Ironically, the same atmospheric obstacle that had kept us so hot and dry eventually helped bring a hurricane to our doorstep.

After crossing mountainous Haiti as a Category-2, Hazel moved over 80°F water near the Bahamas and gained strength. Like Hurricane Hugo before it hit South Carolina in 1989, Hazel did not weaken as it approached the Carolina coast.

Just 15 hours before making landfall, Hazel became a Category-4 with maximum sustained winds of 132 mph. It retained that strength until its landfall at the North Carolina-South Carolina border near the Little River.

While Hazel occurred during the period before which we have radar and satellite imagery for most storms, we can imagine what it might have looked like based on descriptions of its characteristics.

Its eye was 20 to 30 miles across with clouds and rain building north and west of the center because of interactions with a cold front along the leading edge of the approaching trough.

In that sense, Hazel was also a lot like Hugo, so it may have closely resembled the 1989 storm as it neared the coast.

Once Hazel reached land, at least four different factors made it so damaging. At the southern coastline, Hazel hit on the same date — October 15 — as the full moon and the seasonal high tides, which created the worst storm surge our state has ever seen — 18 feet in Calabash.

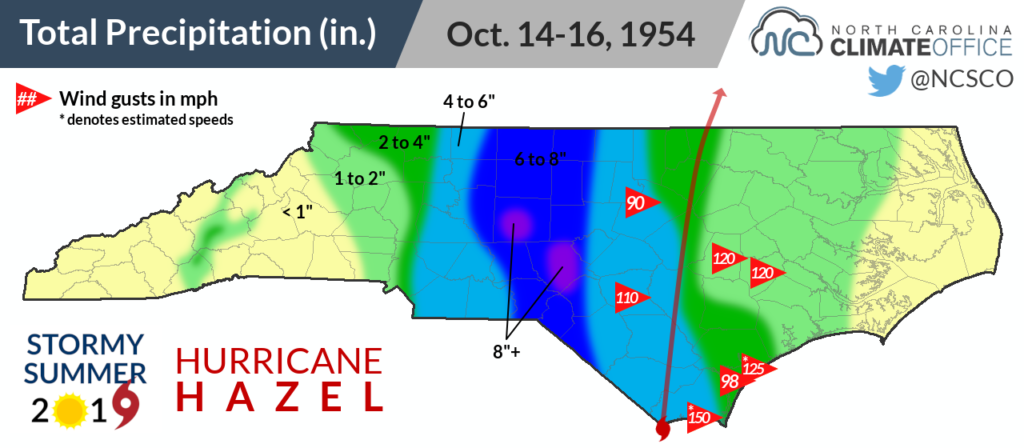

Inland, Hazel’s fast motion gave little time for its winds to decrease and added an extra punch east of the eye. Winds gusted to 90 mph in Raleigh, 110 mph in Fayetteville, and 120 mph in Goldsboro and Kinston, not to mention the gusts estimated as high as 150 mph at the immediate coast.

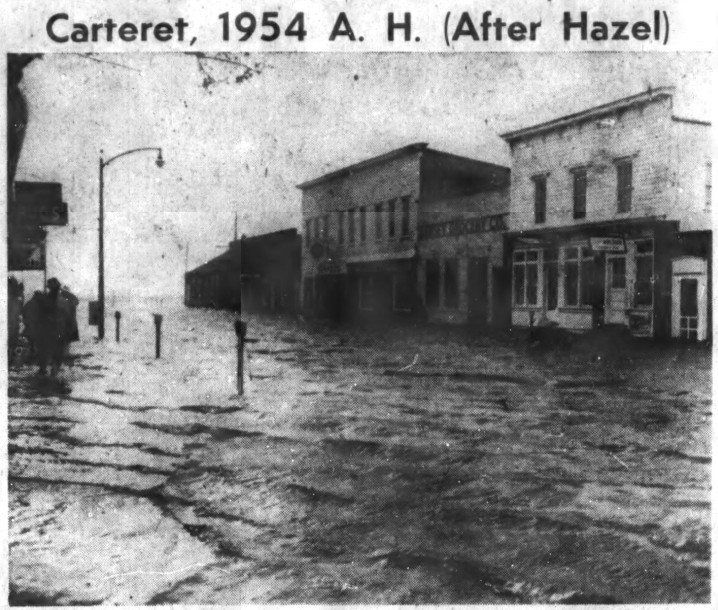

The damage was immense. At Long Beach along the eastern edge of the eyewall, only five out of 357 buildings were not destroyed. Farther from the eye between Cape Fear and Cape Lookout, half of all oceanfront property was said to be damaged.

So affected by the storm was the coast that the Carteret County News-Times signaled it began a new era: “1954 A. H. (After Hazel)”.

Across the eastern two-thirds of the state, “an estimated one-third of all buildings… received some damage” and “hundreds of trees per mile [were] uprooted and thrown flat to the ground” or “twisted off above the ground”, according to a report by the Meteorologist in Charge at the National Weather Service in Raleigh.

Hazel resulted in 19 deaths in North Carolina, many due to drowning, and an inflation-adjusted $957 million in crop and property damage.

Because of Hazel’s fast forward speed — just 12 hours after making landfall, it was over southern Canada — rainfall wasn’t widespread across the state. The highest totals came across the Piedmont, where its precipitation was amplified by the approaching cold front.

While the silver lining of a hurricane can sometimes be drought-busting benefits, in the case of Hazel, it left most of the state wind-whipped but still in a seasonal rainfall deficit.

Maximum Strength

As the strongest hurricane to hit our state based on its Saffir-Simpson scale category and sustained wind speeds, Hazel is an obvious benchmark upon which all other storms are compared.

But is it as strong as a landfalling storm could get in North Carolina?

The academic answer is no, since it’s possible we could have a Category-5 hurricane reach our coast. Someday it may happen, but it would take a record-breaking storm to do it.

Hazel remains the most northerly landfalling Category-4 hurricane in the Atlantic. The only landfalling Category-5 along the continental US Atlantic coast (not including Gulf coast storms) was Andrew in 1992, which hit south Florida.

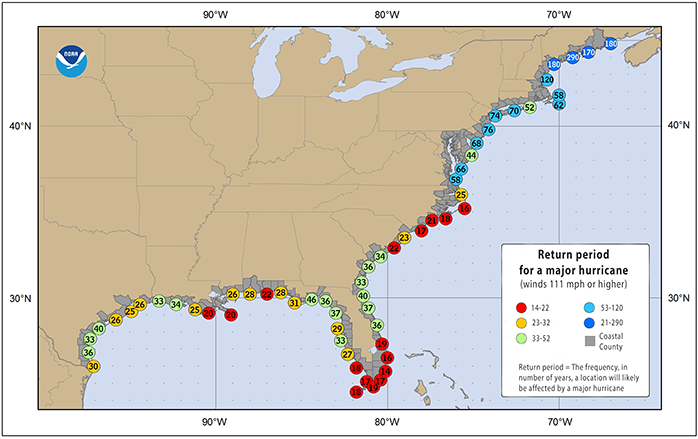

Major hurricanes become increasingly rare moving up the coastline. As storms move out of the tropical environment and into the mid-latitudes, the chances of interacting with large-scale weather systems like cold fronts increase.

While that can provide extra support for heavy rain along one edge of the storm as in Hazel and Floyd, it can also increase wind shear and erode the eye as storms begin an extratropical transition.

The National Hurricane Center estimates a return period for major hurricanes — Category-3 or higher — of about 14 years for the Miami area. That frequency drops to about once every 40 years near Jacksonville, FL.

But that frequency picks up again off the North Carolina coast thanks to the warm Gulf Stream offshore and our state jutting out into the Atlantic. That gives us an estimated major hurricane return period of 16 to 25 years. With our last such storm, Fran, hitting 23 years ago, we’re perhaps due for another.

The Worst-Case Scenario

Of course, category isn’t everything when it comes to hurricanes. Floyd, Matthew, and Florence have all hit since Fran with lower sustained winds but greater damage and death tolls in the state due to their widespread inland flooding.

But what if a storm had both sets of impacts? What would North Carolina’s worst-case hurricane look like?

At the immediate coast, where the greatest damage tends to come from the high winds and storm surge, the combination of ingredients that made Hazel so potent would make for maximum destruction if moved perhaps 50 miles eastward over Wilmington.

In the Coastal Plain, a large storm with a wide radius of strong winds hitting perpendicular to the shore could devastate hundreds of miles of beaches and coastal towns, especially at high tide.

It’s a trajectory scarily similar to the one Florence took, and forecasts during the storm last September briefly showed it taking such a track while holding major hurricane intensity through landfall.

Its eventual encounter with dry air and wind shear off the coast ultimately saved us from such an outcome, although the storm’s slowdown increased rainfall amounts and riverine flooding.

But even in many coastal counties, Florence provided a preview of what an even stronger storm might look like.

Diana Rashash, an area specialized agent in water quality and waste management with the North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service, says that in Onslow County, their worst-case scenario would have many days of heavy rain falling, along with the wind from a storm like Fran or Hazel.

“Florence was pretty darn bad to us because wind was pushing the water upriver while the rainwater was coming downriver,” said Rashash.

“Even though the wind wasn’t very high mileage, it was relentless. Roofs just gave out. Trees just gave out. The roots just gave up.”

In the Piedmont, where Hazel, Fran, and Hugo are generally considered the worst storms on record, the winds from those storms combined with the rain from Florence would also be a cruel combination.

“If you transpose Florence over the Charlotte area along with tropical storm-force wind gusts, that’s pretty much a worst-case scenario,” said Nick Keener, the director of meteorology for Duke Energy.

While Hugo brought damaging hurricane-force winds, it wasn’t a huge rainmaker. Several days of heavy rain could make all of its impacts — power outages, property damage, and flooding — that much worse.

“For electrical transmission, the biggest problem would be the wind,” said Don Ligon from Duke. “For us in hydro, managing the flows would be a bigger issue.”

In the Mountains, where the most memorable tropical storms from 1916, 1940, and 2004 have all caused flooding and landslides, a similar storm or series of storms with record-breaking rainfall over several days could churn up more of the same problems with where that water might end up.

“Now in those sort of events, you just have to hold on,” said David Hanks, Asheville’s water resources director in a 2007 interview with the Mountain Xpress. “There’s just not enough capacity.”

After the 2004 storms, some of the blame for the flooding in Asheville was placed on the North Fork Reservoir, which had little extra space to accommodate the additional rainfall. The city later said opening the spillways only added a few inches to the feet of flooding, but it still highlights the precarious balance between the need for storage in case of a drought — like western North Carolina faced in 1954 — with a more cautious approach in case of a hurricane.

“Today, if we had a similar storm, we would have the same flood,” said Hanks. “If tomorrow there was another hurricane coming up from the Gulf, what we know to do is essentially the same as it was in 2004 — and that’s to open the front door and open the back door and let the flood waters roll through.”

Perhaps no one hurricane would be the worst-case scenario for the entire state. Each region’s own geography, hydrology, and infrastructure create their own vulnerabilities that different types of storms could uniquely impact.

But from Asheville to the Atlantic coast, we at least have plenty of experience to pull from whenever that next big storm arrives.

Any given year in North Carolina can have a stormy summer, and our hurricane history is rich with stories of how they’ve changed landscapes, lives, and left an impression on our state.

Sources:

- Climatological Data, North Carolina – October 1954 from the US Department of Commerce/Weather Bureau

- Hurricane Hazel Event Overview from the National Weather Service in Newport/Morehead City

- Hurricane Hazel Event Summary from the National Weather Service in Raleigh

- Sleeping Giant from Brian Postelle and Kent Priestley, Mountain Xpress, October 10, 2007