When you think of the ingredients for a damaging hurricane in North Carolina, a few things are likely to make the list: major hurricane-strength with high winds, a big storm surge along the coast, and an impact on a large number of people across the state.

Twenty years ago in September 1996, Hurricane Fran ticked each of those boxes and then some, making it one of the most damaging and most memorable storms to affect our state.

A Tropical Reawakening

To understand why Fran’s impacts were so incredible, you have to travel back in time more than 40 years to the last major hurricane that struck eastern NC: Hurricane Hazel in 1954. After leveling much of the southern coast with Category-4-strength winds and a record 18-foot storm surge, Hazel drenched the Piedmont with heavy rains and lashed the landscape with high winds that toppled trees and damaged an estimated one-third of all buildings across the region.

In the four decades after Hazel, the immediate coast suffered glancing blows from several storms including Donna in 1960, Diana in 1984, and Gloria in 1985, all of which were at Category 1 or 2 strength. The western Piedmont sustained its own impact from Hugo in 1989, which despite making landfall in Charleston, SC, was still at Category-1 strength when it reached Charlotte.

However, the southern coast and eastern Piedmont got off largely unscathed during this period of relatively quiet conditions, and those regions experienced huge growth; the Triangle area more than doubled in population. That calm ended during the 1996 tropical season, and Fran became the first major storm some residents would experience in their lives.

Eight weeks before Fran hit, its warm-up act came in the form of Hurricane Bertha. On July 12, Bertha made landfall near Topsail Island at Category-2 intensity. Although Bertha’s inland impacts were limited, it toppled sand dunes and structures along the immediate coastline, which made those areas even more vulnerable to damage from Fran.

A Storm Emerges

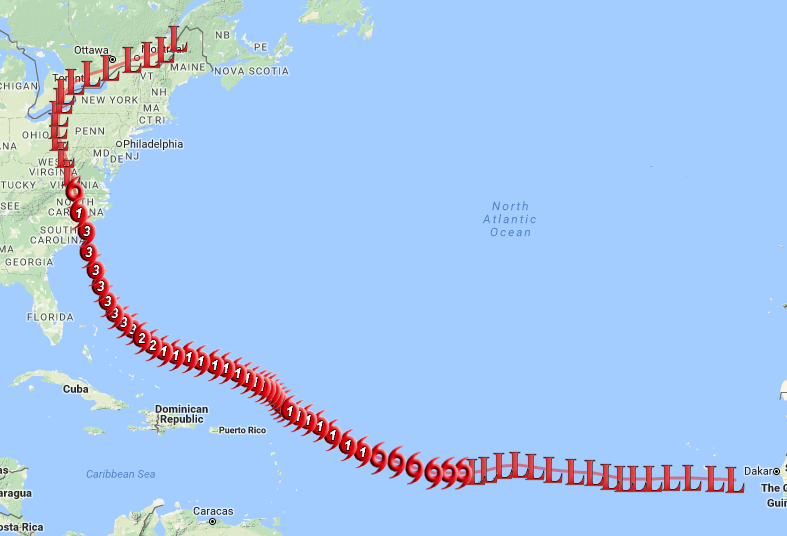

Like Bertha, Fran began its life as a tropical wave that moved off of Africa. Fran wasn’t alone in that journey; it was the second in a line of three tropical systems crossing the Atlantic.

Initially, Fran was far from the headliner of the three. Hurricane Edouard, which led the trio of storms, strengthened to Category-4 status in the mid-Atlantic and was briefly a threat to the Northeast during Labor Day weekend. However, a passing upper-level trough eventually steered Edouard away from the US east coast.

Edouard churned up cooler water at the ocean’s surface, which made development tougher for Fran and Tropical Storm Gustav, which was the third storm in the line and eventually fizzled out in the wake of the two storms ahead of it.

Fran was also slow to develop initially, remaining at tropical depression strength for four days before becoming a tropical storm on August 27. Even after reaching hurricane strength two days later, Fran fluctuated between a Category-1 hurricane and a tropical storm as it moved north of Puerto Rico and Hispaniola.

Once Edouard veered off to the north, Fran underwent rapid intensification. On the morning of September 3, Fran was still a Category 1, but later that night, it had reached Category-3 strength with pronounced spiral bands and a suddenly well-defined eye that was only 600 miles from North Carolina’s southern coast.

Fran Takes Aim

Just 48 hours prior to its eventual landfall, most computer model forecasts predicted Fran to make landfall in South Carolina, taking a track similar to Hugo. However, over the next day, the forecast tracks shifted northeastward, and by the early morning on September 5, North Carolina’s southern coast, including Cape Fear, was in Fran’s sights.

With a hurricane warning in place from Brunswick, GA, through Cape Lookout, NC, the coast braced for impact from the storm that was still at Category-3 strength and showed no signs of weakening prior to its landfall later that night. In towns along the North Carolina coast, 87% of residents evacuated ahead of the storm.

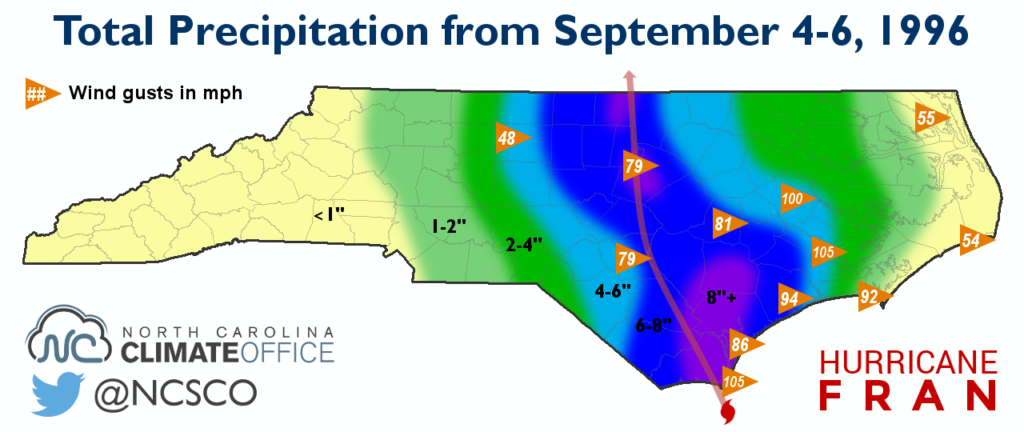

For those that stayed behind, Fran’s impacts began in earnest by the late afternoon on Thursday, September 5. Wilmington received heavy rain with winds gusting to more than 50 mph. Fran’s eye made landfall near Cape Fear just after 8 pm with maximum wind speeds estimated at 115 mph, making it a powerful Category-3 hurricane.

Overnight, Fran’s eye moved inland, tracking just to the west of Interstate 40 from Wilmington through Raleigh. Along and to the east of that path, wind gusts of 100 mph in Greenville and 105 mph in New Bern were reported with rainfall totals of 13.15 inches in Southport, 9.00 inches in Roxboro, and 8.80 inches at the Raleigh-Durham Airport.

Waking Up to Major Damage

On September 6, the sun rose to illuminate scenes of destruction across eastern North Carolina. At the southern coast, the storm surge inundated beachfront communities and destroyed homes, piers, and other structures. That included the temporary police station constructed after Bertha at North Topsail Beach, where the surge peaked at 12 feet. Topsail Island was also bisected by a new 100-foot wide inlet carved out by Fran.

Farther up the coastline, Fran’s easterly winds pushed a surge of water up the river basins. The storm surge reached 10 feet in Swansboro and along the Neuse River in New Bern. In Washington, the 9-foot surge up the Pamlico River was the greatest since September 1913.

Inland, Fran’s one-two punch of heavy rain and high winds softened the ground and ripped up trees by their roots. The downed trees, wind-damaged buildings, and power outages in Fayetteville and the Triangle rivaled the scenes from Hugo seven years earlier in Charlotte and the Triad.

The day after Fran, roads were nearly impassible, covered by flood waters and fallen trees. Twelve days after the storm, 150 secondary roads remained closed. Even two to three weeks later, power remained out in some areas as crews worked to restore service to the estimated 1.7 million customers who lost electricity in North Carolina.

A History-Maker

By any measure, the statistics put Fran firmly among one of North Carolina’s most damaging hurricanes. The 24 deaths in North Carolina attributed to Fran — half of which were from falling trees — rank as the fifth-most fatalities of any storm. And the damage bill of $3.65 billion, adjusted for inflation, ranks as our state’s second-costliest tropical storm behind only Floyd.

That monetary cost includes nearly $2 billion in insured losses and $750 million to North Topsail Beach and Carteret County, where more than 6,000 structures were destroyed or damaged. Almost $900 million in damage came from Raleigh and Wake County, and North Carolina’s agriculture industry took a $700 million hit.

With 41 years having passed since Hazel, Fran became the benchmark hurricane for a new generation in parts of the state. Of course, another reference point would be added three years later when Floyd caused devastating flooding across the Coastal Plain.

From Wilmington northward through the Triangle, no storms since Fran — and, given the population boom and development across that region since the 1950s, arguably few storms before it — have had such a widespread, memorable, and long-lasting impact.

Postcards from Fran

For more about Fran’s impacts, check out these stories from around the state as told by those who endured the storm:

- A Neighborhood Knocked Down, then United, by Fran

- Toppled Trees and the Smell of Sawdust

- Fuel for Fires and Sustenance for Soldiers

- Beyond-Belief Stories from the Coast

Sources:

- Hurricane Fran Preliminary Report by Max Mayfield at the National Hurricane Center

- Hurricane Fran Service Assessment from the US Department of Commerce

- Hurricane Fran: September 5, 1996 by Tim Armstrong, NWS Wilmington