It’s setting up to be a consequential winter for North Carolina, with the fate of a newly emerging drought, along with a potentially record-breaking “snow drought,” hanging in the balance.

In our 13th annual winter outlook, we look at the potential La Niña pattern that could be in place this winter, the climatology of similar historical years, and our expectations for what to watch for this winter.

To summarize the key points:

- A borderline La Niña is developing, although it’s expected to be a weak event.

- La Niña winters tend to be warm and dry in North Carolina, but a weaker pattern could allow for more variability in our weather.

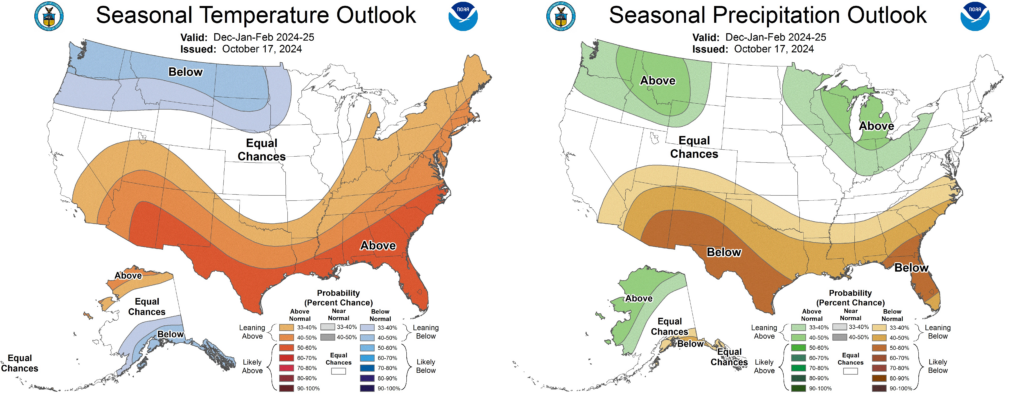

- Our outlook favors above-normal temperatures and below-normal precipitation overall, with fewer chances of wintry weather.

Leaning Toward La Niña

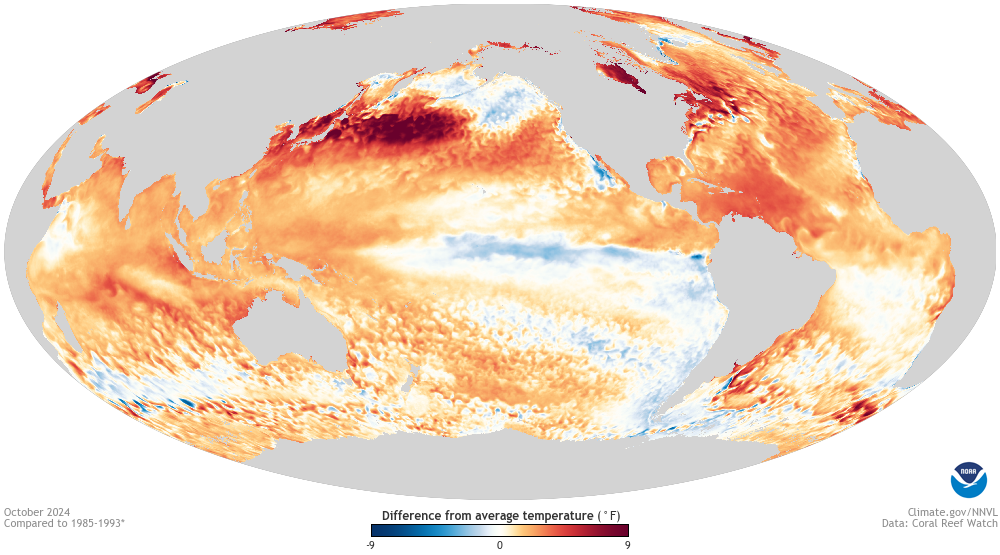

As last winter’s El Niño pattern faded, a transition back to La Niña seemed likely, with most forecast models predicting that Pacific sea surface temperatures would reach the threshold of 0.5°C below normal over the summer.

That expected evolution was one reason why the hurricane season outlook called for so much activity, since a La Niña pattern tends to see a shift and weakening of upper-level winds, and a reduction in wind shear, across the Atlantic basin.

While August through October did see an uptick in tropical activity, including the devastating Hurricane Helene, it’s tough to attribute that to La Niña because that pattern hasn’t officially emerged yet; the latest three-month average Oceanic Niño Index was just 0.2°C below normal.

As NOAA’s October ENSO Blog notes, weaker-than-expected trade winds back in September seem to have slowed the development of this La Niña. Entering the winter, a nose of cooler water has formed across the equatorial Pacific Ocean, and there is some support from cooler water beneath the surface.

But with sea surface temperature anomalies holding steady in the cool neutral range in recent weeks, it’s not a guarantee that we’ll even reach the La Niña threshold this winter. Current model forecasts show a 71% probability of hitting the La Niña threshold in December, January, and February, leaving about a one-in-four chance of ENSO-neutral conditions.

Clues from Climatology

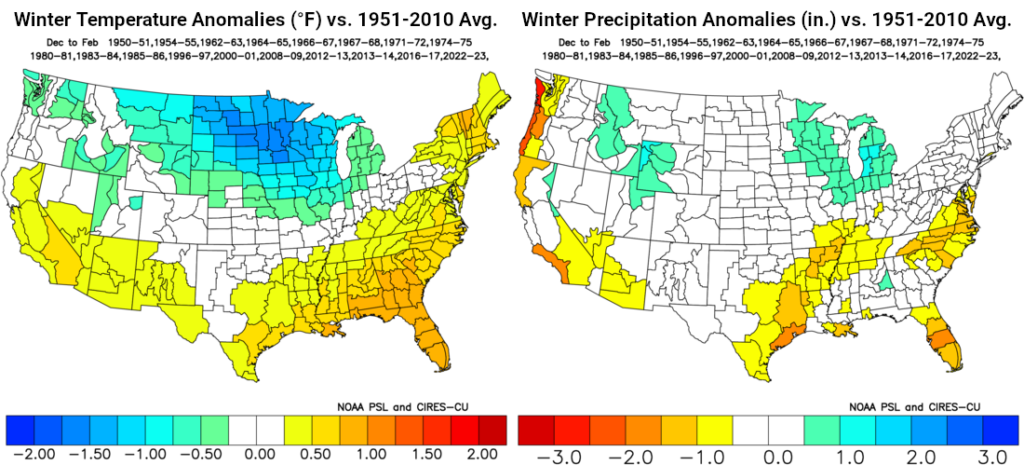

La Niña is typically associated with a weakening of the jet streams across the Northern Hemisphere, which tends to make them a bit wavier and often retreated to the north. That can shift the storm track away from the Southeast, keeping us warmer and drier overall.

We see the same basic impacts even in a weaker La Niña or a cool neutral pattern. Among 18 winters since 1949 with an Oceanic Niño Index between -0.3 and -0.8 – the same sea surface temperature anomaly range as most forecasts call for this winter – we were 0.66°F warmer and 1.06 inches drier than the 20th-century average in North Carolina.

However, both of those are less than the anomalies of 1.77°F warmer and 1.22 inches drier than average during 17 moderate to strong La Niña winters, which suggests weaker events also tend to have less pronounced, or at least less persistent, impacts.

Indeed, during those weaker events, La Niña’s grip on the jet streams is more likely to loosen at some point during the winter, putting our weather in the hands of more local or regional patterns that could break us out of the typical warm and dry conditions, even if only briefly.

We see that reflected in the historical statistics. While 14 of the 18 cool neutral or weak La Niña winters were drier than normal overall in North Carolina, 13 of those winters had at least one wetter-than-normal month. That includes our last encounter with La Niña in 2022-23, which finished with below-normal seasonal precipitation but had a wetter January.

Among those 18 years, three stand out as close analogs that illustrate potential paths our weather could take over the next three months. The winters of 1964-65, 1980-81, and 2016-17 all featured cool neutral or weak La Niña events that were not on the back end of a “double dip” La Niña – which research suggests can have more pronounced impacts – and they were each preceded by variable falls in which conditions started wet before turning dry across the state.

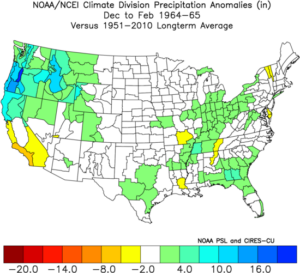

A Wintertime Reset (1964-65)

The similarities between this year and 1964 begin in the fall. Late that September, heavy rain showers set up over parts of the southern Mountains, and the remnants of Hurricane Hilda added even more rain in early October. That ran up weekly totals to more than 15 inches and produced severe flooding, the likes of which areas such as Rosman didn’t see again until this year during Helene and its predecessor event.

By November 1964, we had entered a drier pattern across eastern North Carolina, but the winter that followed featured two months with near-normal precipitation sandwiching a dry January.

That offered a solid wintertime recovery, with the North Carolina Farm Report noting that soil moisture conditions had been favorable for small grains during the winter and “a good quality wheat crop” was expected that spring.

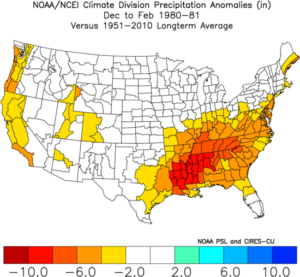

Deepening Dryness (1980-81)

In late 1980, we also shifted from wet in September to dry by October, and eastern North Carolina had been in a persistent dry pattern throughout that summer and fall.

That winter wound up as our 5th-driest on record, with all three months drier than normal statewide, including our state’s 2nd-driest recorded January with only 1.05 inches of precipitation, on average.

That left widespread drought conditions across the Southeast, with some streamflows in North Carolina reaching record low levels by March. We had to wait for summer showers to eventually chip away at our wintertime drought from that year.

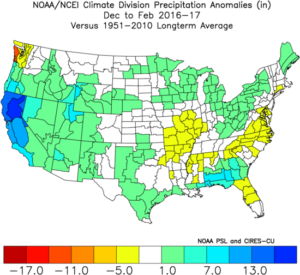

Damage Limitation (2016-17)

Perhaps most memorably among this set of analogs, the fall of 2016 included extremes on either end of the state, with flooding from Hurricane Matthew in the east and widespread wildfires in the west during an emerging drought.

The winter that followed was predominantly warm, especially in our 3rd-warmest February on record, but near-normal precipitation in December and January helped tamp down those western drought conditions, which ultimately faded during the spring.

Before the rain returned in April, we saw some western wildfire activity that March, although it was not as severe as that region had seen in the previous fall.

Our Winter Outlook

It will be a close call whether we actually hit the La Niña threshold this winter, and we’re expecting a weak La Niña event at best, with Pacific sea surface temperature anomalies of no cooler than -0.7°C.

Consistent with NOAA’s winter outlook and the typical impacts of even weaker La Niña events, we’re expecting overall warmer and drier conditions in North Carolina this winter. Recent trends also support that warm outlook: over the past 20 years, 17 of those winters have been warmer than the historical average, including five of our top ten warmest winters on record.

We also expect some wetter periods mixed in, as has often been the case in weaker La Niña winters, although there are few hints of when that wetter weather could manifest. Among 18 historical winters with cool neutral or weak La Niña conditions, 8 were wetter than normal in December and 7 were wetter in January and February.

As the closest analogs among that group illustrate, this winter could see drought evolve in a few different ways, from a net recovery as in 1964-65 to the developing dryness from 1980-81 to partial improvements, but not complete drought recovery, like we saw in 2016-17.

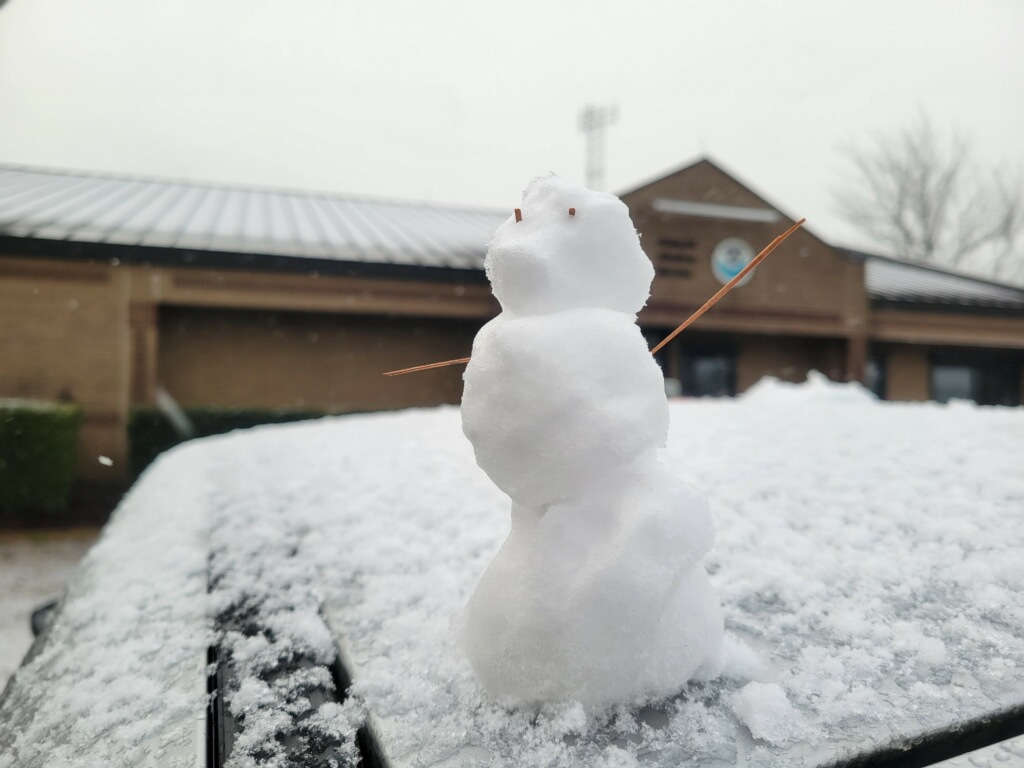

But when waiting for precipitation, don’t get your hopes up for a winter wonderland. We expect few wintry precipitation events, consistent with recent downward snowfall trends tied to climate change and in line with La Niña’s typical impacts, including in the three close analog years we identified.

While 1965 did see a pair of statewide snow events in mid-January and late January, the 1980-81 winter had just one snow event in the western part of the state in March, and 2016 had a similar event in January with the highest totals confined to northern and western areas.

That same result of little snow outside the Mountains has held for the past two winters, which has much of the state going on three years with no measurable snowfall. After last winter, we noted that Asheville and Charlotte have already set new records for their longest snow-free streaks. Other Piedmont sites including Greensboro, Raleigh, and Monroe would set new record-long streaks if this winter finishes without any measurable snow.

If there’s any hope for snow lovers, it may be that the last inch-or-more snow events across much of the state happened in January 2022 – smack dab in the middle of another La Niña winter, when the typical warm and dry pattern broke in favor of a cooler and wetter one.

Ultimately, January may be the decisive month this winter. If we briefly shift to a wetter pattern at our climatological coldest time of year, that could potentially bring an end to both our meteorological drought and the stubborn snow drought.

But if January stays dry, then we could see drought stick around to start the spring, particularly if spring-like temperatures start early again next year. Seven of the past eight Februarys have been warmer than average, including our top three warmest Februarys on record in North Carolina, and a La Niña pattern tends to stack the deck in favor of warmer months like that. If that happens, then watch for a more active early-spring fire season as well.

The strength and persistence of those La Niña impacts will go a long way in sealing our fate, whether it winds up being a classic warm and dry winter or a more variable season with some better rain — and possibly even snow — chances to alleviate our ongoing droughts.