Florence After Five: Redefining the Future

This is the final in a four-part blog post series remembering Hurricane Florence for its five-year anniversary.

The sheer extremity of Hurricane Florence left people across the state – from homeowners to local and state officials – questioning what they believed they knew about hurricane impacts.

After all, the storm and its rain amounts were literally off the charts. Based on historical data as part of NOAA’s Atlas-14 precipitation estimates, a four-day precipitation total of 15.5 inches in Lumberton was believed to be a 1-in-1000 year event.

Florence brought more than double that amount – 35.71 inches – which put Interstate 95, and downtown Lumberton, underwater for days.

Before that water had even receded, questions were coming from every corner of the state.

How do our communities handle this?

Did climate change play a part?

Could a storm like this happen again?

Five years later, we have answers, and they tell the story of a storm that served as a wake-up call for our state, but also one that left plenty of work to be done.

Leading the Recovery

At the state level, the scale of Florence’s damage, just two years after Hurricane Matthew devastated many of the same areas, called for a dedicated response.

In October 2018, only a month after the storm, the state established the North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resiliency, or NCORR. In addition, the governor was interested in establishing a chief resilience officer for the entire state, so that position now rests with NCORR and is held by Dr. Amanda Martin.

“NCORR was formed after Florence because of the need for an agency that would administer what we knew would be a large amount of disaster recovery funds,” said Martin. “After Matthew, it was clear how hard it was to put that sort of money on existing state agencies.”

One of NCORR’s main responsibilities has been directing the ReBuild NC Strategic Buyout Program, which includes identifying buyout zones at risk for future flood damage.

That program – supported by a Community Development Block Grant for Mitigation from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) – is separate from the buyouts administered by FEMA through its Hazard Mitigation Grant Program.

However, both function similarly, seeking to purchase properties from homeowners who voluntarily decide to sell, with those structures then demolished and the deeds transferred to local governments to prevent future development in flood-prone areas.

NCORR has established 17 buyout zones across seven counties – Columbus, Cumberland, Edgecombe, Jones, Pender, Robeson, and Wayne – that suffered significant freshwater flooding from Florence.

Along with helping some of the hardest-hit areas, these buyouts are lifting up families who are often least able to financially recover after a storm.

“Our funding comes from HUD, so with that, we have directives to spend our money on communities that are low to moderate income, for the most part,” said Maggie Battaglin, who serves as NCORR’s Director of Mitigation.

The successes have included the Best family in Goldsboro, who applied to the Strategic Buyout Program and were selected. Now, they’ve got a new home in a safer place a few miles away, while their old property will be converted into green space.

“It’s been really rewarding to see individual families made better and know they’ll see less risk from storms,” said Battaglin.

NCORR also leads the Regions Innovating for Strong Economies and Environment (RISE) program, which is funded by the US Economic Development Administration with in-kind support from NCORR and the NC Rural Center.

RISE brings together stakeholders at a regional scale to identify bigger-picture resiliency issues and opportunities, then work with local communities to develop projects to address them.

One of those local partners has been the Lumber River Council of Governments, which has developed a portfolio of proposed resilience projects, such as restoring or acquiring land in the watershed to hold or slow the movement of water into places like Lumberton.

And working with the Coastal Dynamics Design Lab at NC State University, NCORR helped the town of Whiteville – which has been repeatedly inundated during storms such as Matthew, Florence, and Idalia – apply for a FEMA Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grant.

Last month, Whiteville was selected for that grant, which will support a $3.7 million stream restoration project to help mitigate future flooding in the community of color surrounding Mollies Branch, a tributary of the Waccamaw River.

That’s a great example, Battaglin said, of “bringing capacity to a community, identifying more areas where we can have concentrated flood protection measures, and getting those implemented relatively quickly.”

Altogether, NCORR has invested $779 million in recovery efforts for storms like Matthew, Florence, and Fred. That includes moving more than 1,300 families into new homes, with plans to expand the Strategic Buyout Program to an additional 1,632 properties in the future.

Martin acknowledges there are still hurdles to overcome to build a more resilient North Carolina, including a lack of bandwidth or staff capacity among local governments to undertake large-scale projects, or the often-prolonged steps of designing, permitting, paying for, and managing those projects.

“Recovery is a very slow process no matter where you are,” she said. “Becoming more resilient is also a slow-going process.”

She also noted a lack of affordable housing options, but along those lines, NCORR has committed $110 million to building almost 1,800 new affordable rental units and private multifamily developments.

Risks Remain

When it comes to getting people out of harm’s way, the news since Florence hasn’t all been good, or even in the right direction.

A study by city planning and hydrology researchers at UNC Chapel Hill found that between 1996 and 2017, for every property in North Carolina removed through buyouts, an additional ten have been built in floodplains.

And that shows no signs of slowing down. More than 75,000 acres of vacant land in floodplains is zoned for development, which could put even more homes and families in the path of future flooding.

Beyond their risks to homes, events such as Florence can have cascading impacts throughout local communities, according to recent research by Hope Thomson as part of her work at the UNC Center on Financial Risk in Environmental Systems.

One key finding shed light on how financially impactful Florence and other damaging storms can be.

“Everyone is still somewhat in the dark about how accurate the uninsured losses are,” said Thomson.

After Florence, the insured losses in North Carolina totaled $366 million. Thomson’s study estimated the uninsured losses may have been almost five times as high, or $1.77 billion, including damages and property value decreases.

Those costs have broader impacts. Lower property values mean less revenue for local governments from property taxes, and abandoned homes can lead to blight throughout communities, which makes them less attractive to new residents and businesses.

That has been the case in places like Fair Bluff, another Lumber River town hit hard by Matthew and Florence. With more than 30% of the population living below the poverty line, some families had no choice but to leave after those storms.

Thomson’s research stratified losses by property value, and the results revealed why towns like Fair Bluff have faced such a tough road to recovery.

“It really stood out to me that some of the folks who might be most in need of support might also be the least able to address and recover from these storms,” she said.

Community Concerns

For riverside towns such as Fair Bluff, outmigration and repeated storm events have made the future uncertain.

In the 13 coastal communities collectively called Down East, the realization has set in since Florence that the future won’t look like the past.

After many historic buildings were damaged by Florence and Dorian in Cape Village and Portsmouth Village near Cape Lookout, residents had to make some difficult decisions about how to proceed.

They were assisted by Dr. Erin Seekamp, the director of the Coastal Resilience and Sustainability Initiative and a Goodnight Distinguished Professor of Coastal Resilience and Sustainability at NC State.

As part of a project funded by the USGS Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Center, Seekamp has helped these Down East towns with adaptation planning, focusing on the vulnerability and cultural value of the historical buildings within them.

Some, such as the Baker-Holderness house dating back to 1930, were so badly damaged that demolition was the only realistic option. Other structures could be elevated, moved to higher ground, or rehabilitated using modern and more resilient materials.

“That changes the integrity and character of the building itself, but in terms of the landscape, it’s still there,” said Seekamp.

For these communities with deep-rooted history, seeing any change has been difficult, but it is becoming an unavoidable reality.

“Before Florence, they didn’t want to see them elevated or removed,” added Seekamp. “Today, rather than trying to hold onto a specific structure, they understand that it may be best to remove it, especially if it can’t be functionally the same as before.”

The loss of these buildings, as least as they once looked, is emblematic of two changes happening Down East, and residents aren’t sure that either can be reversed.

“There’s two key concerns,” explained Seekamp. “Climate change and loss of connection of the current generation to these places and their communities.”

In the latter case, fewer economic opportunities in these areas historically based around shrimping and fishing has led some young people to leave.

In the former, the spate of storms from Isabel to Florence to Dorian to Ian – and even the sunny days in between – has made it clear that from the air to the ocean, the environment around us is changing.

“Everybody is very conscious of tides, and there are lots of ghost forests down here. That’s a canary in the coal mine,” said Karen Amspacher, the executive director of the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center on Harkers Island.

“Climate change is real. Everybody has got to have a flood plan. A lot of people are talking about raising their homes, not just for named storms that come ashore, but for the potential flooding that may not be part of an actual hurricane.”

And it’s not just Down East. Florence was an eye-opening event for many who suddenly saw climate change manifested locally, through impacts that scientists had warned about for years.

Simulating the Storm

One of the state’s leading climate change experts is Dr. Rick Luettich, the director of the UNC-led Coastal Resilience Center. He was a co-author of the North Carolina Climate Science Report, which was assembled by a team of climate scientists across the state, including from the State Climate Office.

The report was a key component of Executive Order 80, which was signed by Governor Cooper in October 2018 and focused on climate change and its impacts in North Carolina. It included a summary of changes happening with hurricane strength and behavior.

“The storms are getting stronger, they’re getting wetter, and there’s growing evidence – although it’s still nascent – that they’re moving more slowly in the Gulf and south Atlantic, so that means they have more time to blow winds and push water and cause coastal flooding, as well as heavy rainfall and freshwater inundation,” said Luettich.

“Florence had all the signatures. It was slow-moving, it was big, and it was very wet.”

Luettich is able to see those impacts, both from his current hometown in Morehead City, where there was widespread wind and water damage after Florence, and also using the Advanced Circulation (ADCIRC) computer model he helped develop almost two decades ago.

Initially created to help simulate and understand why storms like Katrina caused such devastating flooding, the model now lets researchers explore how climate change is making them even worse.

For instance, a team at Princeton University used ADCIRC to simulate changes in coastal flood events due to the combined effects of climate change on sea level rise and tropical cyclones. For the southeast Atlantic coastline including North Carolina, they found the historical 100-year flood event should be expected every 1 to 30 years by the end of the century.

“Based on that,” Luettich said, “you can say that the 100-year, 1% water level, must have gone up.”

That affects where floodplains are located, the flood insurance rates in those areas – and Luettich noted the National Flood Insurance Program and the state of North Carolina use ADCIRC to help set those rates – and the design standards for our infrastructure, which Florence laid bare.

Florence in the Future

The North Carolina Department of Transportation was already planning changes to Interstate 95 through Lumberton after Hurricane Matthew in 2016. That storm, by the way, was classified as worse than a 1-in-500-year flood event for the city based on the Atlas-14 estimates, with 12.5 inches of rain in a single day.

When Florence was even worse, NCDOT had to take another look at that project – and fast, before construction began.

They were aided by Dr. Gary Lackmann, a meteorology professor at NC State, and his graduate student Katy Hollinger, who have extensive experience with modeling hurricanes, including how those storms may look in our future climate.

While their forecast model can produce detailed, high-resolution simulations of a storm, the science behind those future environmental changes is straightforward.

“It’s basic thermodynamics,” said Lackmann. “A warmer environment will support more water vapor.”

Increasing the background air temperatures in the model to levels expected at the end of the century – the sort of lifespan NCDOT hopes for from a new bridge – offers clues about how a storm like Florence might look in the future.

The results are almost unbelievable.

“The present-day Florence was so bad, you think ‘could it get any worse?’” said Lackmann. “The answer is it gets a lot worse.”

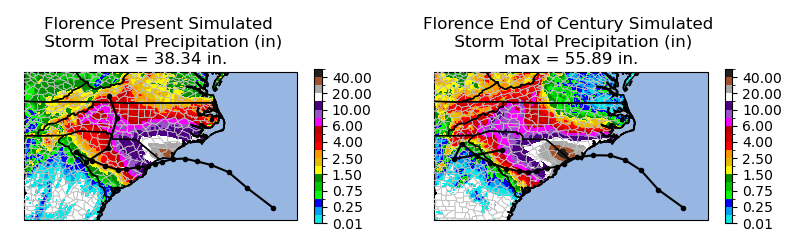

Hollinger noted that the simulated Florence in a 2018 environment had a similar maximum strength as the real storm, and a maximum rainfall of 38.34 inches – on par with the highest observed total of 35.93 inches.

In the simulated end-of-century conditions, the minimum pressure falls to 942 millibars – not far off Category-4 Hazel’s 938 millibars at landfall in 1954 – and the maximum precipitation balloons to 55.89 inches.

In addition, the area receiving at least 20 inches of rain almost doubles and the area with at least 30 inches increases by 334%.

While that could be considered a worst-case scenario given the unmitigated emissions scenario used in the model, that’s exactly the idea NCDOT had in mind in funding the study.

“They’re mainly using our runs for stress testing,” said Hollinger. “If we raise a bridge by 10 feet, does it withstand that future Florence or does it still go underwater?”

For Matt Lauffer and his colleagues at NCDOT, those results, along with other projections of future precipitation changes, have given confidence – and quickly – in adjusting their plans.

“The amazing story is what happened on I-95. That project was almost in construction, and we changed the entire design standard from Benson to mile marker 13 south of Lumberton due to that event,” said Lauffer. “Highway projects take decades sometimes, but by 2026, you’ll have a resilient Interstate 95.”

The insights of this modeling extend far beyond the bridges through Lumberton. Over the past five years, Florence has served as a case study for finding points of failure and strengthening those weak links.

“With Florence, there’s so much water that no matter what you do, there’s going to be so much road under water,” said Lackmann. “But what you can do is for the city of Wilmington, make sure there’s at least one route that stays above water.”

For NCDOT, the changes since Florence have included a different approach to future planning.

“It got the department thinking about resilience, like for the Alligator River bridge that we’re building,” said Lauffer, “so they can be more resilient to the future climate conditions we’re expecting, including sea level rise.”

He added that they’re also looking at equity, such as how to take care of disadvantaged communities, as part of their long-term planning. After all, those towns are more than just stops along the road. Somebody calls them home – and they want to keep it that way.

Questions Answered

Those big questions from five years ago now have clearer answers, illuminated by the research and recovery efforts across North Carolina.

How do our communities handle this?

Getting people out of flood-prone areas, such as through the NCORR-administered Strategic Buyout Program; helping communities better understand and identify tangible projects to address their vulnerabilities, as with the RISE program; restoring wetland areas so they can absorb some of the impacts from freshwater flooding; and adjusting our roads and bridges so they can withstand the floods, are all good ways to start.

Did climate change play a part?

Basic atmospheric science, confirmed by recent research, tells us climate change is making storms stronger, wetter, and maybe even slower.

“All of those are what you might call fingerprints that reflect what we might see in a changing climate, already happening over the past few decades,” said Luettich.

And it’s not just affecting our worst storms. Inch by inch, rising sea levels are causing sunny day flooding Down East and literally leaving coastal wetlands for dead, weakening one of our last natural lines of defense against the storm-stirred ocean.

Could a storm like this happen again?

Florence was an extreme event, no doubt, but the number of systems like it is growing.

In 2015, an upper-level low fed by tropical moisture from the fringes of Hurricane Joaquin inundated South Carolina and parts of southeastern North Carolina.

In 2016, there was Matthew, which Lackmann notes had higher rain rates than Florence – and Hollinger suggests “is the scariest of the storms in terms of our future changes” because of the increase in the intensity and extent of those rain rates in her model runs.

In 2017, there was Harvey, which dropped 60 inches of rain over east Texas while sitting nearly stationary for days.

By 2018, of course, we had Florence – still our state’s costliest and wettest hurricane on record.

Since then, we’ve seen more rainfall totals measured in feet over Texas from Tropical Storm Imelda in 2019, along the Gulf coast from Hurricane Sally in 2020, in western North Carolina from Tropical Storm Fred in 2021…

“We think so locally, but when you look collectively, globally at the weather extremes, it’s a much larger sample size,” said Lackmann.

So can a storm like this happen again? It already has, even if it’s not always in North Carolina.

That awareness, perhaps, and the changes it inspires, will end up as Florence’s lasting legacy for our state.

- Categories: