Five Years Later, Five Lessons Learned from Matthew

It’s a rare storm that now stands out more for its similarities to, rather than its differences from, others in its era.

Five years ago today, Hurricane Matthew brushed the North Carolina coastline but still caused incredible inland impacts. It wasn’t our first modern hurricane to produce significant freshwater flooding — Floyd in 1999 held that distinction — but it also isn’t the latest, with Florence in 2018 inundating many of the same areas affected by its predecessors.

As has become clear over the past five years, if Floyd was our nightmare, then Matthew was the wake-up call, reinforcing the drenching danger posed by tropical systems far from the coastline.

With the benefit of hindsight, and through the voices of those who experienced Matthew and its impacts first-hand, here are five lessons learned from and since that storm.

Skip Ahead: Forecast Messaging | Inland Flooding | Infrastructure | Agriculture | Future Planning

Track and intensity don’t tell the full story.

On its way to North Carolina, Matthew sent forecasters for a loop — and it nearly went for one itself.

After crossing the Bahamas at Category-4 strength, some model forecasts showed Matthew grinding up the Southeast coastline before looping out to sea and eventually doubling back toward the same areas, effectively boxed in by high pressure developing to the north.

While it avoided such an unusual track, its actual track and evolution didn’t make things any easier for National Weather Service offices in the path of the storm.

Despite weakening to a Category-1 and being projected to remain mostly off the North Carolina coast, Matthew still carried the threat of significant impacts far away from its center.

“Matthew was a great example of why we have to constantly reiterate in our messaging to not focus on the skinny black line on the forecast map and understand that the forecast cone is not an impact cone,” said Steve Pfaff, the Warning Coordination Meteorologist at the National Weather Service in Wilmington.

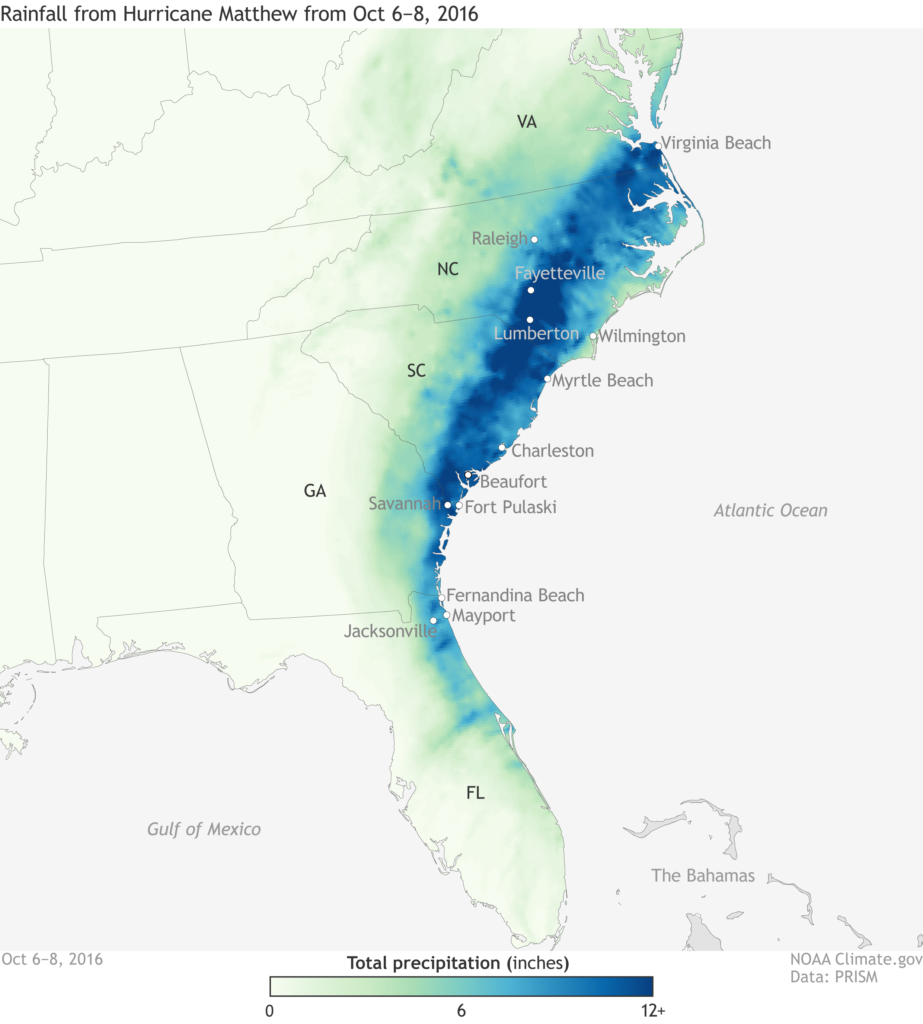

Indeed, while Matthew’s eroding eye never made landfall in North Carolina, a foot of rain fell up to 100 miles inland in areas that may have assumed themselves safe from the worst of the storm.

Predicting exactly where the heaviest rain — and the worst flooding — would occur also created a forecasting and communications challenge.

“I remember that while excessive amounts were expected, the distribution of the axis of heaviest rainfall was still in question since it would not take much of a shift in the storm’s track to make huge differences in where the rain fell,” said Pfaff. “Subsequently, that would have an impact on which river basins would be hardest hit with the subsequent flooding.”

The nuances of which regions could have seen such extreme totals can be difficult to display, especially when users are accustomed to seeing only one forecast amount for their location.

“We convey that uncertainty in our briefings to emergency management and the media, but getting the message about the uncertainty to the public is a challenge, especially when deterministic information is readily available on our websites and in some of our products,” said Rick Neuherz, the Service Hydrologist at NWS Wilmington.

Even after the rain had ended, the meteorological threat posed by Matthew wasn’t over. A period of strong winds on the back edge of the storm knocked down trees and power lines in the rain-weakened ground, leading to more hazards.

“Anyone who was tracking the radar could have easily assumed that the wind threat would be diminishing as the precipitation exited,” said Pfaff. “We had to issue several messages to advise that the situation was not improving, and in fact winds were going to be worse at the end of the event.”

With impacts far from the center of the storm and hours after it had stopped pouring on eastern North Carolina, Matthew demonstrated a difficult lesson in communicating potential hurricane havoc.

Inland and urban flooding demands more attention.

On September 29, 2016, a long-lived thunderstorm dropped up to 10.5 inches of rain over Cumberland County, surging the Cape Fear River and its branches. Excess water breached the river banks and control structures like the Rhodes Pond Dam, then cascaded into downtown Fayetteville, Fort Bragg, and surrounding communities.

At that time, Matthew had just reached hurricane strength over the Caribbean, more than 1,500 miles to our south.

Nine days later, when the storm made its rendezvous with North Carolina, the additional 14 inches of rainfall it brought to the Fayetteville area sent the Cape Fear rising once again.

The September 29 thunderstorm had set a new record high crest of 31.20 feet on the Little River at Manchester, breaking a long-standing high water mark from 1945. On October 10, the floods from Matthew quickly eclipsed that peak, hitting 32.19 feet.

At least 17 dam failures were noted in North Carolina after Matthew, according to the News & Observer, and 13 of those were in the Cape Fear basin, urged along by that antecedent rainfall a week before the hurricane hit.

For the National Weather Service in Raleigh, which covers some of the hardest-hit locations along the Cape Fear and Neuse rivers, the inland and urban flooding impacts in places like Fayetteville weren’t necessarily a surprise, but they were unexpected for some people in the affected areas.

“The perception was that it was always going to be a southeastern North Carolina event,” said Jonathan Blaes, the Meteorologist-in-Charge at NWS Raleigh. “A lot of things pointed to this being a rainfall problem, but it’s not going to be cataclysmic. Fayetteville had a lot of rain before; hopefully, they’re going to dodge it this time.”

They didn’t, of course, and one reason for that was a shift in the forecasts ahead of the storm. A service assessment conducted by NWS noted that while official forecasts were generally accurate, “the forecast issued 48 hours prior to the storm’s closest approach to both South and North Carolina… indicated that the storm would move eastward and away from the coast.”

“That’s a big deal,” said Blaes. “The rainfall forecast that the public and the River Forecast Center uses is based on the official National Hurricane Center track forecast, so that meant it was shifted 120 miles to the south.”

When those rainfall bullseyes eventually repositioned as the forecast was adjusted, they targeted not the coastal counties but those farther inland. That potential for impacts away from the coast, especially amid an uncertain forecast, was one of the main lessons learned from Matthew.

“There were no flooding fatalities in a county in North Carolina that touches saltwater,” said Blaes. “The news and the public focuses so much on the dunes and the surf zone, but in this case, so much of the damage and death happened inland.”

Of the 29 deaths attributed to the storm in North Carolina, 24 were due to drowning. In that regard, Matthew helped shift the focus for the National Weather Service in terms of hurricane impacts.

That started at the local office level. The damage in Cumberland County led NWS Raleigh to increase their involvement in areas like that during later storms.

“Matthew was one of the steps in realizing things we needed to do in a service aspect,” said Barrett Smith, the Senior Service Hydrologist at NWS Raleigh. “In Florence, we were sending people to places like Fayetteville to help.”

That increased coordination — with local municipalities, NC Emergency Management, the US Army Corps of Engineers, and others — has helped the National Weather Service and its partners better understand and respond to flooding threats, such as the dam failures during Matthew.

“Relationships with the National Weather Service helped people understand the risk, such as Wilmington and Morehead City using wording like ‘potential for the worst flooding since Hurricane Floyd in 1999’,” said Diana Thomas, a Meteorologist and Planner with NC Emergency Management.

“Groups huddled to discuss hot spot locations that would experience flooding, areas that may require evacuation, and pre-positioning resources in anticipation of major impacts that would affect life and property. These activities were improved in future storms including Hurricane Florence.”

At a larger scale, the National Hurricane Center has changed how it messages hurricane impacts on its website.

“It used to focus mostly on the wind field and the track. Now on those web pages, rainfall is promoted more,” said Blaes.

In addition, the National Weather Service’s hydrology component has taken a step forward with the launch of the National Water Model, which can predict streamflow levels and velocities using high-resolution forecasts.

While inland flooding may never get the attention that it deserves, the improved forecasts and coordination should increase awareness for the next storm, and that’s thanks to the lessons learned from Matthew.

Our infrastructure was due for an upgrade.

Some of the most unbelievable scenes during Matthew — and later, in Florence — were stretches of major highways and interstates completely under water, effectively turned into new river branches by the overwhelming flood waters.

The North Carolina Department of Transportation (DOT) manages roadways across the state, and the sheer scale of Matthew’s impacts presented a major response and recovery challenge.

First, there were the local roads that became impassable due to the flooding.

“That single storm had the most pipe washouts of any that DOT has dealt with,” said Stephen Morgan, the State Hydraulics Engineer.

In total, 728 drainage pipes were washed out during Matthew and more than 2,100 roads required repairs, per a USGS report about the storm. And that was only the start of the infrastructure impacts.

Rising flood waters in Fayetteville and Lumberton eventually reached the travel lanes of Interstate 95, closing a 60-mile stretch of the road for the weekend after Matthew, with some sections shut down for as many as 10 days.

That made a hypothetical successor to Floyd a reality for DOT, and much sooner than anyone may have expected given the statistical rarity cited for a storm like that.

“It’s one thing to talk about a 50-year, a 100-year, or a 500-year event, but when I-95 is closed for a week, it puts you in a different frame of mind,” said Morgan. “You’re telling people moving from north to south or south to north to avoid North Carolina or find a different way around.”

Flooding on the interstate in Lumberton was only one sign of a much larger problem in that area. Morgan said Interstate 95 effectively acts as a levee for the city, so as water spilled over the highway and through a railway underpass, it created the worst flood to that point in Lumberton’s history.

“There’s a transect of how our roadway system can move people and goods and services, but it also has some responsibility with protecting the public,” Morgan added. “The same thing happened with Floyd. A lot of places flooded that hadn’t flooded before, especially in vulnerable and less-affluent communities.”

Even as the water was subsiding and pipes were being replaced, DOT was already at work planning for the next storm, whether on the ground, in the office, or even in the cloud, technologically speaking.

Those organizational improvements started with better tracking DOT’s assets — a necessity, given the number that were damaged and needed to be replaced.

“The way we report, collect, and share that information has changed tremendously after Matthew,” said Andy Jordan, the State Hydraulics Operations Engineer. “The number of eyes on our current inventory has improved since Matthew. We know what we have on the ground, and we know what we have in our yards.”

Their move from spreadsheets into platform-based collaborative software now allows for simultaneous editing by multiple users and more easily sharing information and recommendations within divisions and with executive leadership.

Matt Lauffer, the State Hydraulics Design Engineer, said Hurricane Matthew also precipitated the development of new partnerships and tools for tracking flood-prone areas.

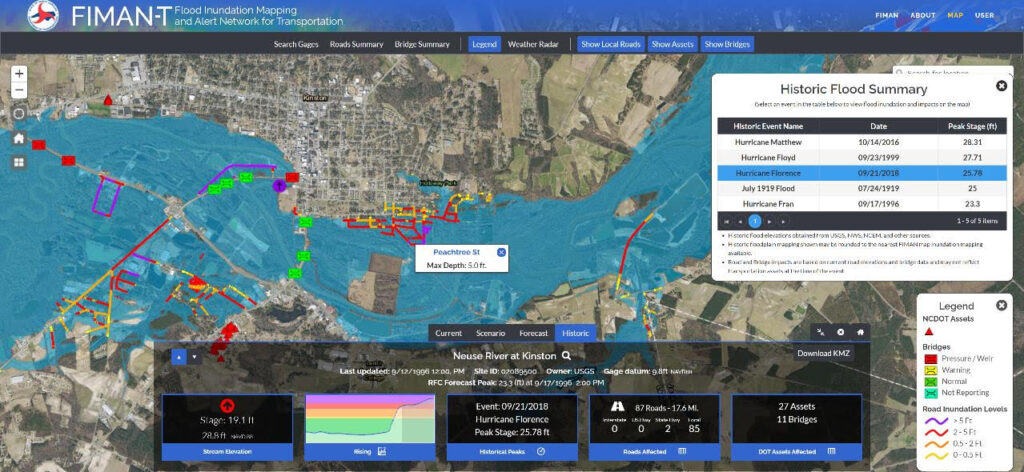

“We needed to be in the joint operations center with emergency management, so we went there during Florence and started the development of FIMAN-T,” said Lauffer, referencing a version of the Flood Inundation Mapping and Alert Network tool designed for transportation. It’s shown below visualizing the extent of flooding in Kinston from Hurricane Florence.

That collaboration has also included the development of three river basin studies of the Lumber, Neuse, and Tar rivers, with each outlining recommended mitigation strategies for the most flood-prone areas.

A separate partnership with the NC Department of Environmental Quality (NC DEQ) and the National Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) has produced a tool called DamWatch to help monitor potential dam failures like the ones seen after Matthew.

For areas such as Lumberton that were inundated in that event, changes are coming to reduce the likelihood of significant roadway closures during future storms.

“When those designs are completed and constructed by 2026, we will have raised I-95 high enough to maintain its mobility and connectivity during a storm like Florence,” said Lauffer.

Those advancements and modernizations to keep people and goods moving around the state might not have been possible — or necessary — if not for a storm like Matthew.

Flooding on farms can turn feasts to famines.

The agriculture industry in North Carolina has a can’t-live-with-them, can’t-live-without-them relationship with hurricanes.

In some areas, rainfall from tropical systems makes up nearly a fifth of the average warm-season precipitation — a figure that has almost certainly increased in the past decade thanks to storms like Matthew.

Years without that moisture can plunge into droughts, and farms tend to bear the brunt of that damage. During our 2007 drought that saw only one minor tropical storm in Gabrielle, the ag industry in North Carolina suffered losses of more than half a billion dollars.

But when a season’s worth of rain falls in less than a week, as in Matthew and Florence, farmers face a different set of challenges that can yield the same result: a loss of their livelihoods.

Matthew’s timing in early October effectively wiped out a summer’s worth of productivity for many crops in eastern North Carolina.

“The biggest impact that I can remember is the loss of whatever crops were in the field,” said Dalton Dockery, the Columbus County Extension Director for NC Cooperative Extension. “We still had crops like sweet potatoes, soybeans, cotton in the ground, and had just begun harvesting peanuts.”

Crop production data from the US Department of Agriculture shows the sort of hit that North Carolina farmers took that year. Compared to the drought-free 2014 growing season, the tobacco harvest was down by 27% in 2016 and the cotton harvest was 64% lower than two years prior.

In total, crop and livestock losses in the state due to Matthew were estimated at $400 million. That included 1.8 million chickens killed by the flooding.

Richard Goforth, a Specialized Area Poultry Agent with NC Cooperative Extension, was on the ground at poultry farms in Matthew’s wake to help with composting the mortalities. He said the lay of the land limited the steps farmers could take to protect their flocks.

“Down east, it’s so flat and low and level that we’re talking a foot to 18 inches of water is all it took to get inundated, and the birds are right on the ground level in the shavings on the floor,” Goforth noted.

After what had already been a wet summer in eastern North Carolina thanks to rain from tropical storms Hermine and Julia, soils were saturated and the additional water from Matthew had few places to go but piling up in the fields, poultry houses, and barns.

In advance of the storm, some poultry producers moved birds to houses or farms less likely to flood, while Dockery said other farmers prepared by doing “things like making sure ditches were clean, consulting with NRCS Soil & Water about what they could do in terms of addressing any drainage problems they may have.”

Those were lessons learned from Floyd, which was a billion-dollar disaster for North Carolina agriculture. However, Dockery notes that truly mitigating for storms of that magnitude is difficult.

“It’s basically the same land that is being planted on a rotational basis and there is no way to reshape all of that land for better drainage, or it would be extremely expensive to do,” he said.

“Even if they could, with that much water, I’m not sure that the results would have been any different.”

One way that Matthew was different than Floyd was in the spillover from wastewater lagoons — or the relative lack thereof. The Natural Hazards Center at the University of Colorado notes that 50 lagoons flooded and six were breached after Floyd, sending a surge of sludge into nearby waterways and, eventually, into the ocean.

During Matthew, flooding was limited to six lagoons and two breaches, both on a hog farm in Greene County, according to NC DEQ. Much of that reduction was thanks to measures taken since Floyd, including buyouts of 42 farms and the decommissioning of 103 lagoons located in floodplains, supported by the state’s Clean Water Management Trust Fund.

Following Florence, Goforth said cost-share funding became available to help poultry farmers relocate outside of floodplains, and some were taking advantage of it, especially on farms too old or too damaged to rebuild in the same spots.

The spate of recent storms has also taught hog farmers preventative steps to help reduce the risk of lagoon flooding.

“Efforts are made to lower the liquid levels of lagoons in a safe and approved method prior to hurricane arrivals, especially if they know in enough time to do so,” said Dockery.

But that’s the critical part: time. And there often isn’t enough of it for farmers.

After Floyd, they learned to run their tractors 24/7 to harvest as much of their crop as possible prior to a storm.

In the 48 hours before Matthew, the forecast shifted, leaving vulnerable farmers even less time to prepare.

For farmers — and others across North Carolina — the new question is what they’ll do in the time before the next storm hits.

It was a sign of things to come.

The wait for Matthew’s meteorological successor didn’t take 500 years or 50 years or even 17 years, like after Floyd.

Only two years later, Florence stripped away Matthew’s title as our worst flooding hurricane, with more than double its rainfall amounts and more than triple its damage bill — an estimated $17 billion, compared to $4.8 billion from Matthew.

For some even in the weather forecasting community, the accelerated rate at which these inland flooding hurricanes is occurring — now three within a 20-year period, from Floyd to Florence — has come as a shock.

“I was confident after Matthew I’d see no more huge floods like that one in my career, but after Florence I no longer have that confidence,” said Neuherz with NWS Wilmington.

“I guess the lesson was that even though you just had the big one, it doesn’t mean there isn’t another big one coming soon.”

From rain to river crests to costs, broken record after broken record, and big one after big one, flooding hurricanes are our future. And that future is happening now.

The North Carolina Climate Science Report, which summarizes changes in our climate and their impacts statewide, notes that “tropical cyclones are expected to produce heavier precipitation, and the strongest storms are projected to be even stronger in the future.”

Because of that, they establish that it’s likely — or at least a two-in-three chance of occurring — that increases in extreme precipitation will lead to increases of inland flooding in North Carolina. (The uncertainty is down to the circumstances of individual flooding events, such as the land over which the rain falls and the presence of antecedent moisture as with Floyd and Matthew.)

This assessment, and these recent storms, have already encouraged some groups across the state to rethink their future plans.

“Intensity is increasing from these events,” said DOT’s Lauffer, pointing to the Climate Science Report, which identified that those trends are expected to continue.

“We’ve learned a lot about climate and how it might be changing,” added Morgan. “Maybe that wasn’t a 100-year storm. Maybe that was a 25-year storm.”

After Matthew and Florence, the state Secretary of Transportation commissioned a flood resilience feasibility study for interstates 40 and 95. Its findings are already being implemented into design plans, such as building bridges to handle a 100-year flood event with an extra foot-and-a-half of freeboard to boot.

Identifying solutions isn’t as easy for all storm-affected groups across the state, but Matthew and Florence have at least forced folks like farmers to take note of our changing climate.

“I think they have an increased awareness that these storms are playing a major role in the general ag industry,” said Dockery. “They are more concerned about extreme precipitation events and how these events are affecting their farms, but they’re not quite sure what can be done about it, other than trying to fix land drainage issues.”

The widespread flooding and livestock losses in these events has certainly made poultry farmers pay attention.

“They’re keen that these events can strike areas that haven’t historically flooded, that are miles from a stream or river,” said Goforth. “They started being more proactive about knowing where the houses with a higher potential to flood were, and where houses that hadn’t previously flooded were in the floodplains.”

At the state level, more consideration is being given to help agriculture better weather these storms. As reported by the Coastal Review, the General Assembly approved legislation last year “to create an inventory of natural and working lands that could be used in flood control and potential incentives for private landowners to do stream restoration and wetlands enhancement and build flood-stage capacity.”

There’s a good reason for that focus on working lands such as farms and forests. A statewide 2017 greenhouse gas emissions study found that these areas “offset 25% of the state’s current greenhouse gas emissions,” or more than twice the average rate of other states.

The farm fields across North Carolina are our breadbasket, but they may be part of the key to managing and mitigating our future climate risks as well.

The recent storms beginning with Matthew have also gotten groups across the state working together more closely, from the Department of Transportation to NC Emergency Management to the National Weather Service to cities and towns that have borne the flooding impacts.

As Morgan from DOT put it, “one event brought together a lot of disparate ideas.”

From an emergency response standpoint, that collaboration has become a necessity.

“Matthew required a whole community approach to recovery,” said Thomas from NC Emergency Management. “The magnitude of the need required federal, state, local, private sector, and non-profit agencies to develop creative solutions to recovery and communication following large disasters. Results from this work include the State Disaster Recovery Task Force and a well-informed North Carolina Hurricane Guide.”

Those new partnerships should ultimately yield improved forecasts, communications, and infrastructure for future flood events.

Resiliency measures take time — there’s that word again, time — to be crafted and implemented, but they represent important steps in securing our state and our livelihoods against the impacts of flooding hurricanes.

Storm after storm, though, the aspects that aren’t as easily repaired are the broken hearts and broken lives of those they affect.

“To go visit a place after it floods is heart-wrenching,” said Blaes from NWS Raleigh. “Tornado surveys are one thing, but the flood water, the mold, the slime, the mud is everywhere. It’s emotional and it lasts so long.”

It has only been five years since Matthew, and parts of eastern North Carolina are assuredly still recovering: financially, structurally, emotionally.

With a little luck, a lot of cooperation, and a memory of the losses and lessons learned from Matthew, we’ll be better prepared to handle the next similar storm when — not if — it occurs.

Section header photos by NOAA via phys.org, the Fayetteville Observer, NWS Wilmington, NC DEQ via the Coastal Review, and NC DOT.

- Categories: