While the rain reigned in eastern North Carolina last month, the western Piedmont stayed dry and has seen a degradation on the state drought map. Plus, how do our temperatures compare to the recent records out west?

From Really Dry to Record Wet

In some months, a statewide average acts as a good representation for conditions all across North Carolina. June was not one of those months, especially in terms of our precipitation.

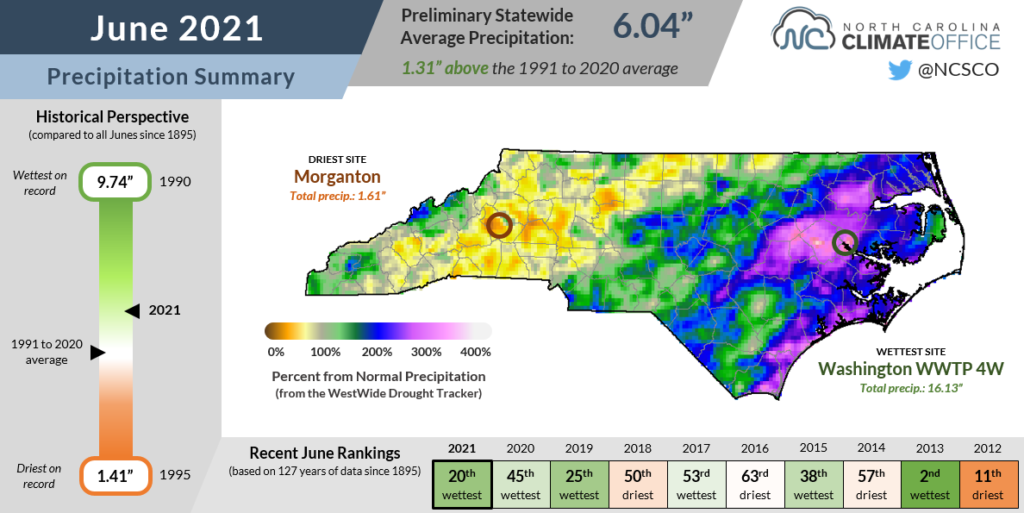

According to the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), the preliminary statewide average precipitation last month was 6.04 inches, which ranks as the 20th-wettest June out of the past 127 years. However, that number obscures the extremes in precipitation from east to west.

The first two weeks of the month were marked by heavy rains across the eastern half of the state from a stalled frontal boundary on June 2-3 and long-lived showers and thunderstorms on June 9-11.

A drier week followed those deluges, but then along came Claudette. After making landfall on the Gulf coast, it remained remarkably well-organized and maintained tropical storm strength over eastern North Carolina on June 20-21.

Along with producing an EF0 tornado in Chowan County and wind gusts up to 53 mph at the southern coastline, Claudette brought more than 2 inches of rain to parts of the southern Piedmont and Coastal Plain.

Those multiple heavy rain events made it one of the wettest Junes in eastern North Carolina, which was a sudden change after one of their driest springs.

Greenville recorded 15.05 inches for its wettest June in 89 years with observations, and it followed the 9th-driest spring there. It was also the wettest June in Washington (16.13 inches) and Ocracoke (12.36 inches).

Wilmington followed its 2nd-driest spring with its 2nd-wettest June dating back to 1874, measuring 12.26 inches during the month. New Bern also had its 2nd-wettest June with a monthly total of 10.72 inches of rain.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the western Piedmont missed out on most of the rainfall, including from Claudette, and had a very dry June.

Hickory recorded only 1.73 inches of rain all month and its 9th-driest June on record since 1949. Morganton had 1.61 inches and its 16th-driest June since 1880. And with 2.55 inches, Marion had only about half of its normal June rainfall.

Dryness Pivots Westward

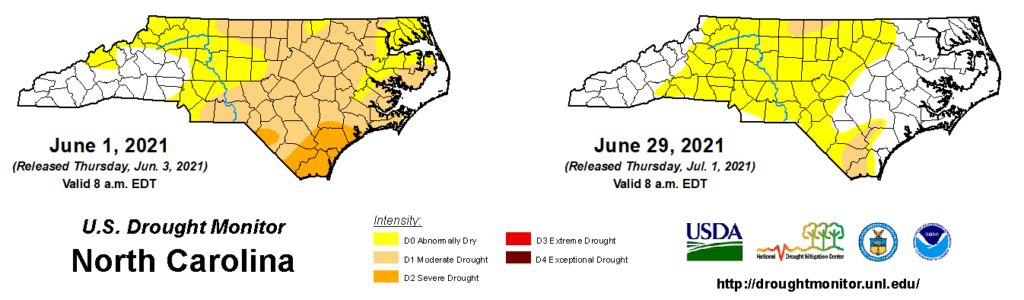

One month ago, Moderate Drought (D1 on the US Drought Monitor’s classification scheme) covered most of eastern North Carolina, with Severe Drought (D2) at the southern coastline.

June’s rains targeted many of these drought-affected areas, and as a result, we’re entering July with a better-looking but still-busy drought map.

The Severe Drought is gone, but a small sliver of Moderate Drought remains in the southern Coastal Plain. That region is still below its normal rainfall over the past three months, and streamflows on the Waccamaw River in western Brunswick County have not fully recovered yet.

After fading earlier in the month, Moderate Drought returned to the northern Piedmont this week, especially in parts of Rockingham, Caswell, and Person counties that are also at a precipitation deficit dating back to the spring.

Several dry weeks in the upper Roanoke River basin have decreased inflows into Kerr Lake, which is about 2 feet below its seasonal guide curve, according to the US Army Corps of Engineers.

A new addition to the drought map this week, the western Piedmont and southern Foothills are now classified as Abnormally Dry (D0), reflecting the lack of recent rainfall and its environmental response, such as decreasing soil moisture content.

Surface water conditions such as streamflows and groundwater haven’t yet dropped below normal in this region, but that doesn’t mean they’re not on the decline. After surging during the winter and early spring, levels have been steadily dropping, and a few more hot, dry weeks would effectively burn through that surplus storage.

Warm Weather, But Not Like the Northwest

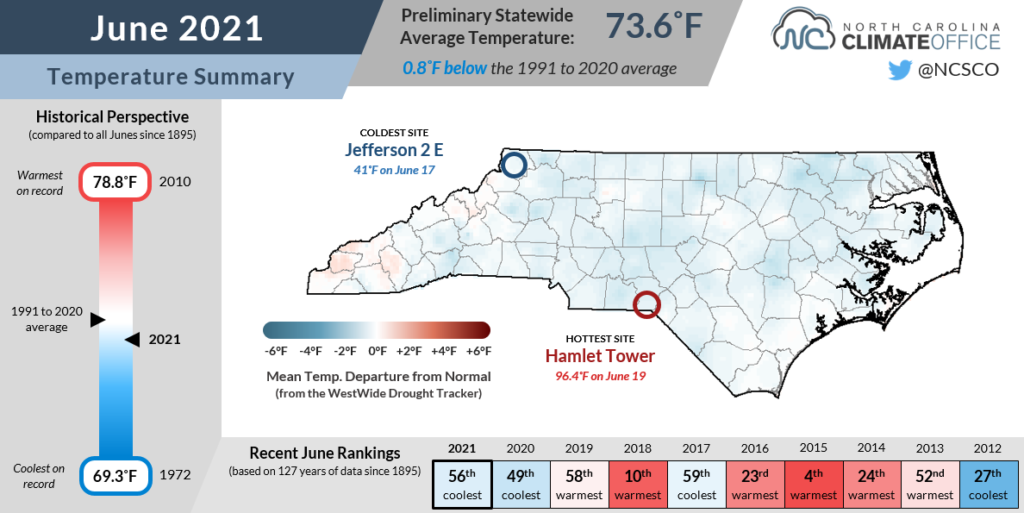

The stretch of summer-like heat to close out the month couldn’t fully offset those cloudy, rainy days early on, yielding slightly below-normal temperatures overall. NCEI reports a preliminary statewide average temperature of 73.6°F, or our 56th-coolest June since 1895.

Most sites across the state finished the month within a degree of their average June mean temperatures. The warmest spots relative to normal were along the Outer Banks, including Hatteras, which measured its 9th-warmest June on record.

While our temperatures were mostly unremarkable in North Carolina, that hasn’t been true everywhere in the country. Notably, June ended with extreme, record-breaking heat in the Pacific Northwest. Exacerbated by climate change, heat waves like this one are expected to become longer-lasting and more intense in that region, coupled with more frequent droughts and wildfires, as the Fifth Oregon Climate Assessment summarized.

For some local context on how unprecedented the recent weather has been in that region, consider part of North Carolina with similar typical June temperatures. In Boone, the normal June high temperature is 75.8°F, compared to 74.3°F in Portland, OR. (It’s no wonder, then, that about 30% of homes and apartments in Portland don’t have air conditioning, according to a 2015 US Census Bureau survey.)

A far cry from that mild climate, though, Portland recorded a new all-time record high temperature of 116°F on June 28. (Boone peaked at 78°F on the same afternoon.) Furthermore, the highest temperature on record in Boone, set on July 27, 2005, is 93°F — a full 23 degrees cooler than the new Portland record!

Of course, the summertime climate of North Carolina differs from Oregon’s because of our higher humidity, which tends to dampen our temperature variability and make such extremes almost unreachable.

When Fayetteville set our statewide record high of 110°F on August 21, 1983, the dew point was at 66°F that afternoon with a relative humidity of 25%. That’s compared with only 12% humidity in Portland when it hit 116°F last Monday.

That 1983 heat wave was set up by a stifling high pressure system that migrated in from the west, so is there any chance that the current Pacific heat dome might take a similar track?

Probably not, as most forecasts have the hottest air moving over the northern Plains through the weekend. More seasonable air should settle in across North Carolina behind today’s cold frontal passage.

For now, Boone and the rest of North Carolina are safe from triple-digit temperatures, and at least in part, we can thank — or blame — our mainstay muggy summer weather.