Our new website launches next week, and we’re using it to help illustrate a warm March that dried out in some areas but remains generally saturated after our wet winter.

A New Website On the Way!

Next Monday brings an exciting new update for our office, and for anyone in North Carolina who uses weather and climate data. Our new website features a brand new system for accessing weather station observations, and it will be faster, easier, and more comprehensive than ever.

To tease a few of the capabilities of this new data request and visualization interface, we’ll share graphics generated with it throughout this blog post.

If you’d like a step-by-step overview of this new system, you can still register to join us for our launch webinar on Monday, April 5 at 11 am.

Warm Weather Helps Us Play Catch-Up

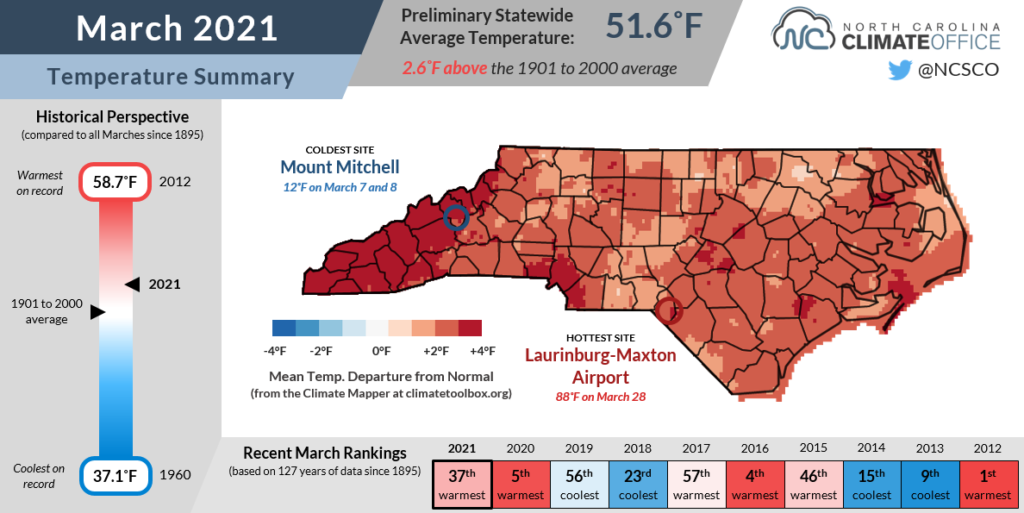

By the end of February, we finally broke out of winter’s cool, icy grip, and that spring-like weather carried over into March. The National Centers for Environmental Information reports a preliminary statewide average temperature of 51.6°F, or our 37th-warmest March since 1895.

That statewide temperature was 2.6°F above the long-term average, but sites on either side of the state were even warmer than that. The sunny coast had a warm month, including the 8th-warmest March at Ocracoke, which was 3.0°F above average.

A steady flow of humid air from the south also kept temperatures in the southern Mountains well above normal. Asheville tied for its 8th-wettest March on record with an average temperature of 51.1°F, or 4.0°F above the historical average.

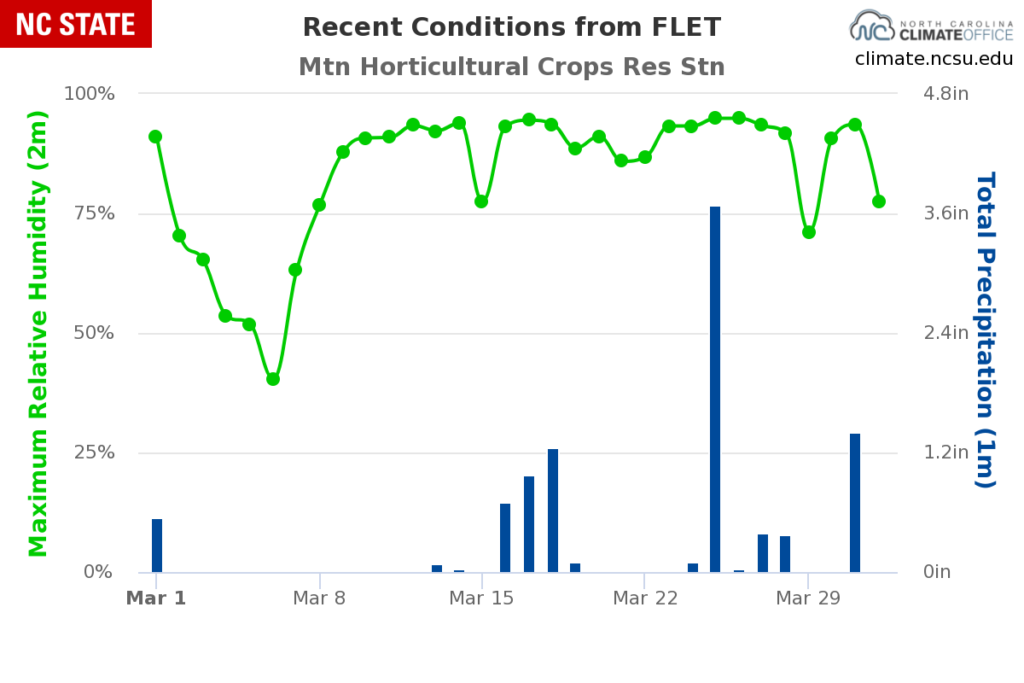

With our new data retrieval system, it’s easy to quickly view graphs of recent conditions. As an example, our ECONet station in Fletcher, just south of Asheville, routinely had daily maximum humidity values exceeding 90% last month, plus some wet days with up to 3.68 inches of rain on March 25:

Despite our warm March, average temperatures so far this year are still running behind last year’s pace, which accelerated during our 5th-warmest March on record. After three months, 2021 is tracking as our 47th-warmest year on record, compared to a tie for the warmest year at this point in 2020.

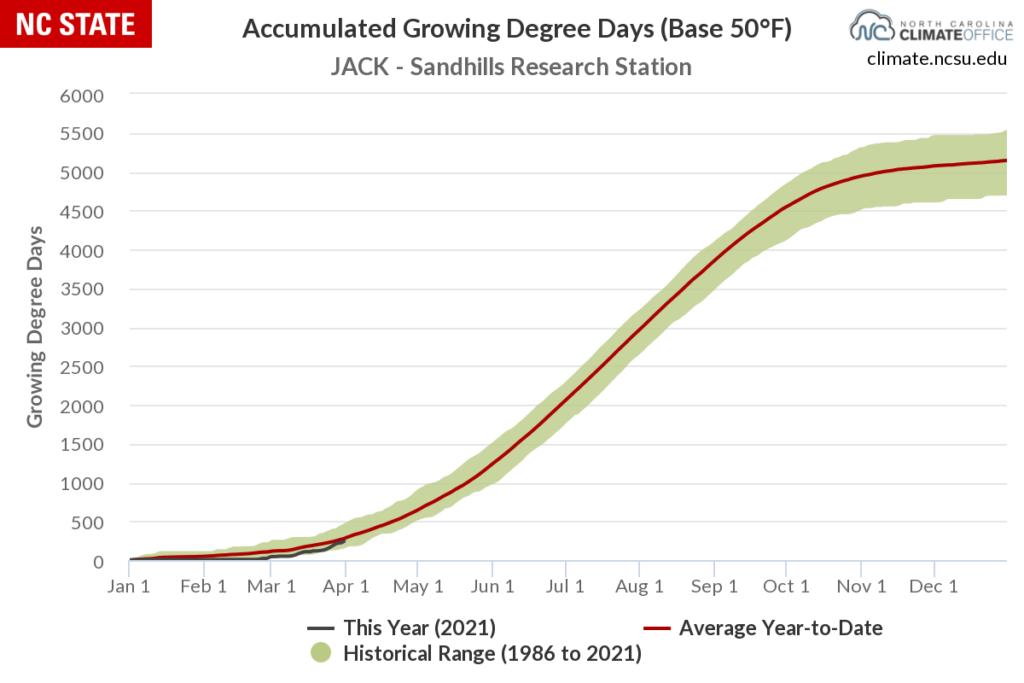

One impact of our cooler February has been a comparatively slower start to the growing season. That can be measured using growing degree days, or the accumulation of temperatures above a certain threshold at which crops grow and mature.

A number of crops use a threshold value of 50°F, and we hadn’t had many days with average temperatures that warm until early March. As a result, locations like Jackson Springs — where our ECONet site at the Sandhills Research Station is in the heart of North Carolina’s peach-growing region — had one of their slowest starts to the growing season in recent memory, and have only recently approached the historical year-to-date average:

A Wet Month in the Mountains, Wet Fields Elsewhere

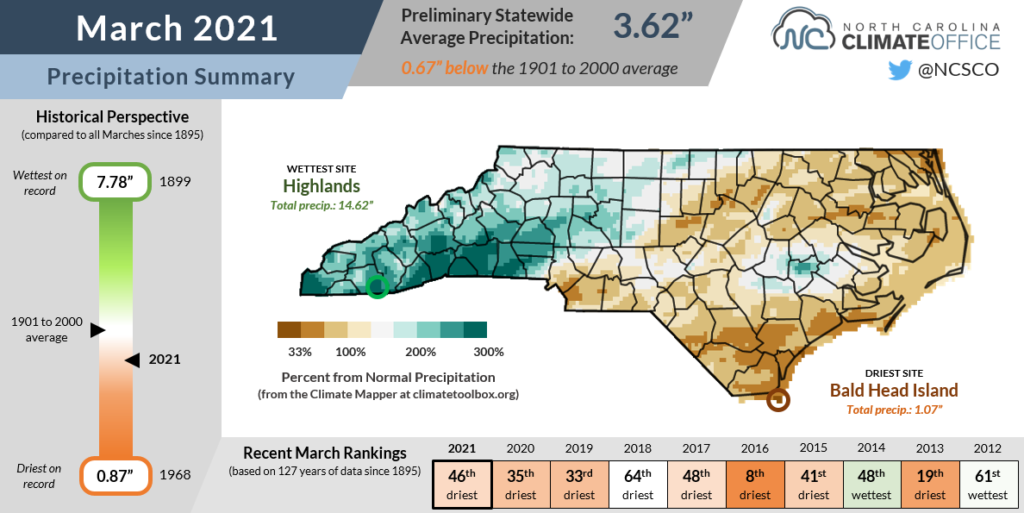

March saw a mixture of wet weather in the southern Mountains while a drier pattern emerged across the eastern half of North Carolina. Overall, it ranked as a slightly drier-than-normal month, as NCEI’s statistics show a preliminary average precipitation of 3.62 inches, or our 46th-driest March out of the past 127 years.

Compared to February, the storm track generally shifted off to the west in March. That meant incoming cold fronts still soaked the far western part of the state but dried out as they crossed the Mountains.

For those southern slopes that saw rain, it was a soggy month. Highlands recorded 14.62 inches of precipitation and its 10th-wettest March since 1879, while Brevard had 12.35 inches and its 6th-wettest March dating back to 1902.

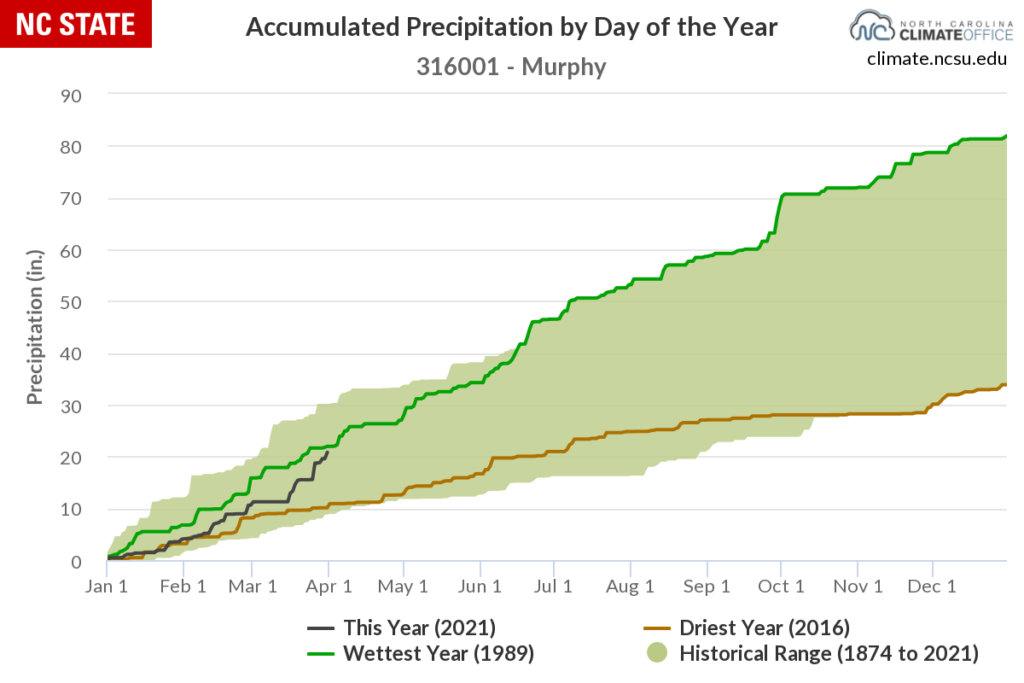

In far western North Carolina, Murphy received 10.19 inches and its wettest March since 1980. Its accumulated precipitation graph for the year-to-date shows how that site recovered from an Abnormally Dry start to run almost even with 1989, which eventually became wettest year on record there:

For the rest of the state, which slogged through our 13th-wettest winter on record, the dry March shouldn’t have been too objectionable, and that surplus moisture has kept any signs of dryness from emerging so far this spring.

Streamflows remain at or above normal in most areas, and soil moisture levels have only declined at the immediate coast, which was the driest spot in the state last month.

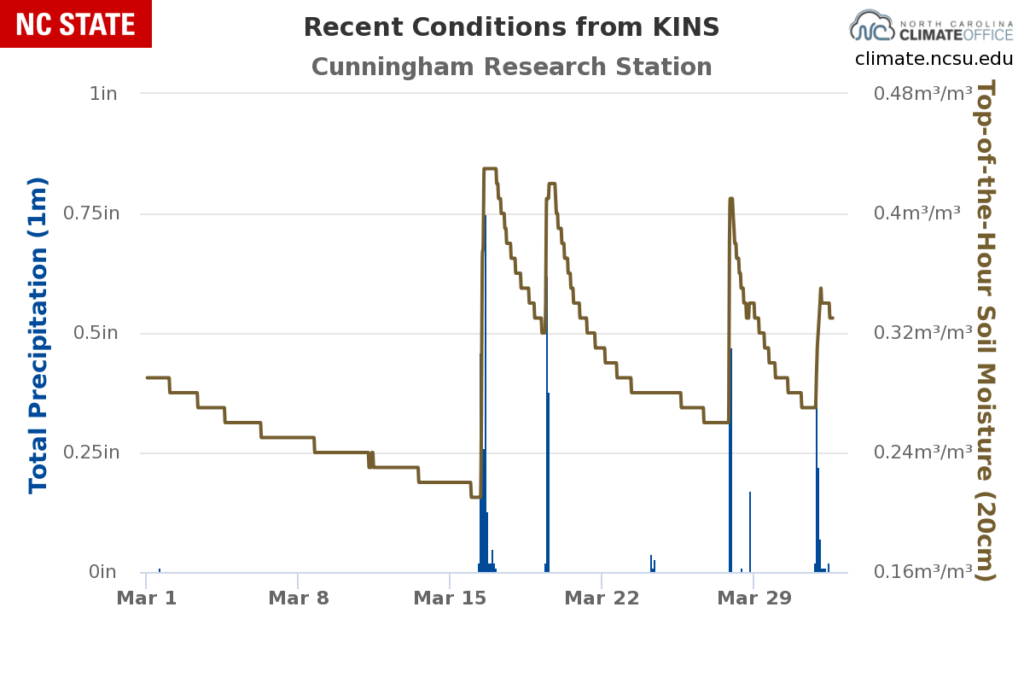

Soil moisture observations from our ECONet site in Kinston, at the Cunningham Ag Research Station, show how conditions dried out briefly mid-month, but actually finished the month wetter than it started thanks to our regular rain events in recent weeks:

Crop progress reports suggest that in some areas, fields are beginning to dry out enough for winter wheat harvesting and springtime planting to begin:

The county continued to receive more than adequate rain. Field work has started but available days to work remain limited due to wet conditions. Wheat looks good.

From Wake County, March 28

The weather was a bit drier and warmer this month. These improved conditions allowed farmers to begin field preparations for this year’s crop season. Sections of the County still have too much soil moisture to get into certain areas. Many of the county’s winter wheat fields have benefited greatly with increased growth due to the warmer temperatures.

From Bladen County, March 28

All in all, it has been a frustrating few months for farmers, who have struggled with excess moisture since last fall. With a new growing season upon us and planting slow to occur, they now face the problem of water, water everywhere but not a crop to drink it.