Whether you’re an ardent believer in their forecasts or just an interested outside observer, the colorful collection of weather folklore provides plenty to talk about as we head into the winter. Before we release our office’s winter outlook on Thursday, let’s take a look at how some of this famous folklore suggests our winter might play out.

The Woolly Worm

Its origins may be in New York, but the tale of the woolly worm as a weather forecaster now calls North Carolina home thanks to the Woolly Worm Festival held each October in Banner Elk. During that event, contending caterpillars race up strings with the overall winner providing winter predictions via its black and brown colored bands.

During this year’s festival on October 21 and 22, the winning worm, “Aspen,” featured a broad brown midsection, supposedly foretelling average temperatures from late December through mid-February. Black bands at the head and tail of the worm are said to suggest cool, snowy weather at the beginning and end of the winter.

Is there any truth to the woolly worm folklore? Perhaps a bit, but not as a weather forecaster. While we found winning worms’ winter predictions are only accurate about 50% of the time, woolly worms may provide some indication of climatic conditions.

Brown bands appear as worms molt, or shed their skin, and warmer conditions in the previous spring can encourage worms to grow more quickly. So perhaps Aspen is just reminding us of conditions last spring — the 26th-warmest on record across the state.

Farmers’ Almanacs

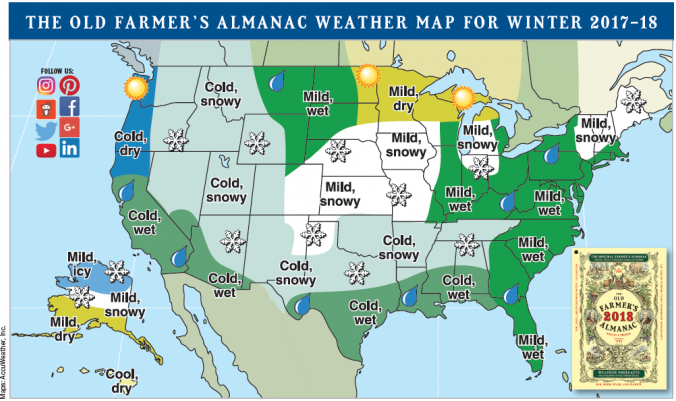

With a history tracing back to the likes of Benjamin Franklin, farmers’ almanacs have long been a source of winter forecasts in the US. Nowadays, two predominant almanacs — the Farmers’ Almanac and the Old Farmer’s Almanac — continue to offer annual predictions.

For this winter, both almanacs expect wet weather for North Carolina. The Farmers’ Almanac predicts “wintry chill” with “wet and white” conditions, while the Old Farmer’s Almanac indicates wet but mild weather is likely for the Carolinas. It also predicts below-normal snowfall with the best chances for snow in early January and early February.

Both almanacs’ exact forecast ingredients are kept secret, even hidden under lock and key. However, we do know that historically, almanac forecasts have been based on a combination of climatology, astronomy — such as sunspot cycles — and astrology, including the positions of the moon and planets. Similar to the woolly worm forecasts, winter predictions from the farmers’ almanacs tend to be hit or miss, with about an equal percentage of each historically.

Snow, Then Some Mo’?

Bugs and books aside, some winter folklore is based around the weather itself. Perhaps the most famous such legend in North Carolina says that if you hear thunder in the winter, it will snow 7 to 14 days later. (We found this was only true about one out of every seven times, so it’s far from the guarantee your grandparents might have suggested.)

A similar adage says that if there is snow on the ground for three days, we’ll have more snow in 10 days. So does this one fare any better?

To test this saying, we combed through National Weather Service Cooperative Observer station reports since 1950 to find instances with snow reported on the ground for three consecutive days. Then we looked ahead to see if any snow was reported 9 to 11 days later, providing a small buffer to the 10 days the legend prescribes.

| Station | Times with snow on the ground for 3 days | Snow events 9 to 11 days later | Recurrence rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boone 1 SE | 319 | 115 | 36.1% |

| Asheville Airport | 208 | 73 | 35.1% |

| Greensboro Airport | 183 | 41 | 22.4% |

| Raleigh-Durham Airport | 115 | 15 | 13.0% |

| Charlotte Douglas Airport | 64 | 8 | 12.5% |

| Wilmington Airport | 17 | 1 | 5.9% |

| Elizabeth City Airport | 42 | 2 | 4.8% |

| Cape Hatteras | 8 | 0 | 0.0% |

As you might expect, this happened most often in the Mountains, where snow is more common. At the 99 Mountain stations, there were 13,196 historical instances with snow on the ground for three consecutive days. Out of those cases, it snowed again roughly 10 days later 4,579 times, or 34.7 percent of the time.

In the Piedmont, this snow recurrence rate was 12.5 percent, while across the Coastal Plain, snow on the ground for three days was followed by more snowfall in ten days 8.8 percent of the time.

Again, that’s far from a guarantee in any region, but those numbers do represent an increase of two to four times over the climatological likelihood of seeing snow during any given three-day period in the wintertime. These odds range from 10.7 percent of the time in the Mountains to 5.0 percent in the Piedmont to 2.9 percent in the Coastal Plain.

Considering that it generally has to be a fairly significant snow event or a fairly cold pattern for us to keep snow on the ground for three straight days, it makes sense that the pattern may remain favorable for more snow a week or two afterwards.

So the next time snow seems to linger, you may consider keeping your shovel out for a bit longer. The stats suggest that snow on the ground does boost our chances of seeing more. Of course, remember that given North Carolina’s fickle relationship with wintry weather, no bits of folklore — not even the fastest worms or the oldest adages — can tell us for sure when snow might fall.