The summer of 1996 was a wake-up call of sorts for North Carolina’s coastline. Prior to that, it had been ten years since the last hurricane landfall — Charley in 1986. Besides a near miss from Hugo in 1989, which made landfall in South Carolina and caused damage across the Piedmont, North Carolina’s coast had largely gone unscathed.

Although the 1996 Atlantic hurricane season was a normal one based on the number of named storms — 13 total — anyone who lived in eastern North Carolina can tell you that it was far from a normal season for them. Two landfalling hurricanes in an eight-week period between July and September brought an end to that decade-long storm drought and literally changed the landscape of our coast.

Bertha and Fran so dominated the headlines and memories from that summer (and for good reason) that it’s easy to forget the tropical season started with another visitor to the North Carolina coast. In mid-June, Tropical Storm Arthur formed over the Bahamas and moved northward before making landfall near Cape Lookout: a track remarkably similar to the 2014 hurricane of the same name.

Arthur’s 1996 incarnation was relatively weak with impacts in North Carolina limited to high surf and some gusty winds offshore. However, it set the stage for the season’s first hurricane — and another direct hit for North Carolina — less than a month later.

Storm Development

On July 5, a tropical wave off the west coast of Africa was classified as Tropical Depression 2, then upgraded to Tropical Storm Bertha just 12 hours later. As the storm became better organized over the warm waters of the eastern Atlantic, Bertha gained hurricane strength on July 7 and reached its maximum intensity as a Category-3 storm on July 9 with sustained winds of 115 mph.

In retrospect, Bertha’s intensity may not get the credit it deserves, both because it weakened in the following days and because Fran upstaged it by maintaining Category-3 strength until landfall. However, a storm as strong as Bertha that early in the season is a rare event.

Bertha was the first early-season major hurricane since Alma in 1966, and in the 20 years since 1996, only three storms in the months of June or July have reached Category-3 intensity or higher: Dennis and Emily in the active 2005 season, and another Bertha in 2008.

As 1996’s Bertha reached peak strength just north of Puerto Rico, the storm began to curve to the north along the western edge of the Bermuda high. Some model forecasts briefly struggled with this change of direction, but they soon adjusted and showed the coast of North Carolina in Bertha’s likely path.

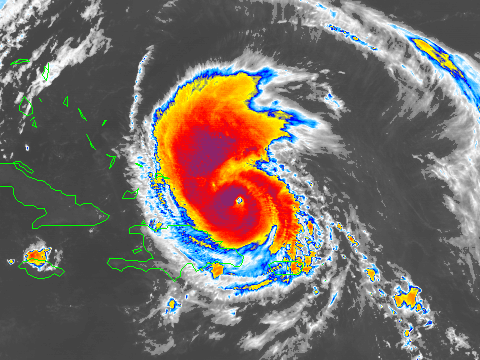

While the storm continued moving northward, its intensity fluctuated. Over the Bahamas, dry air and vertical wind shear caused it to weaken back to a Category 1 and take on a distinctly ragged appearance as clouds eroded on the western side of the eye.

In the 12 hours prior to landfall, Bertha regained some of that lost strength over the warm Gulf Stream, reaching Category-2 status again on the afternoon of July 12. By that point, Bertha’s outer rain bands had already moved over North Carolina, stretching across half of the state.

Impacts in North Carolina

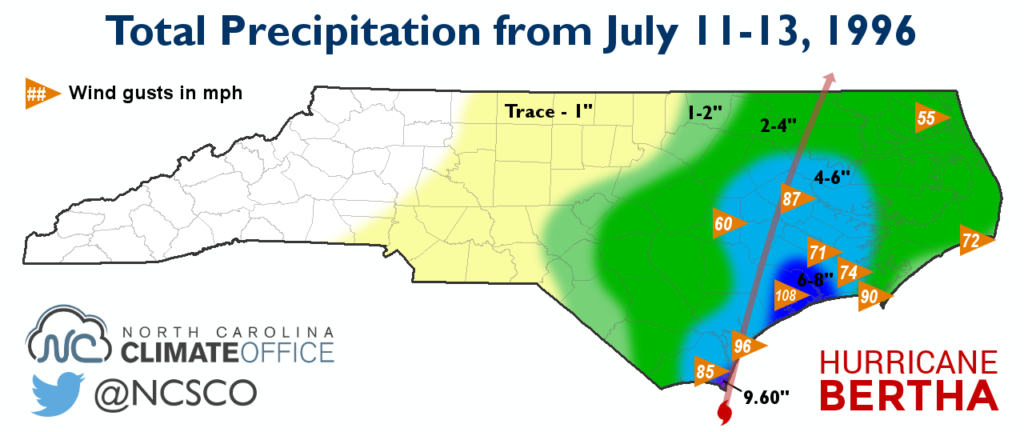

The eye approached the southern coast, eventually making landfall around 4 pm between Wrightsville Beach and Topsail Island. Areas on either side of the eye received the brunt of the storm’s impact. On the western edge, Southport received 9.60 inches of rain in a three-day period.

The eastern side of the eye also saw heavy rain — 7 inches fell in a single day in Hofmann Forest — along with winds gusting as high as 108 mph at the New River Marine Corps Air Station. That location was in Bertha’s powerful right-front quadrant, where the storm’s forward motion of around 17 mph added an even greater punch to its already strong winds.

The coastline from Cape Fear to Cape Lookout saw a storm surge of 5 to 6 feet, which inundated streets and businesses, toppled piers, and together with the high winds damaged more than 5,000 homes. Water and sewage services were knocked out, which delayed the return for some of the more than 100,000 residents who were forced to evacuate.

Bertha also altered the coastline in several ways that became particularly important in subsequent storms. The storm surge flattened sand dunes, so they provided little resistance when Fran’s surge of up to 12 feet came ashore two months later.

On Wrightsville Beach, which was imperiled by Bertha’s surge and inundated by Fran’s, renourishment projects — dredging sand from one area and depositing it on beaches — began in earnest. Those efforts, although somewhat controversial, are credited with saving the beach from heavy damage when Hurricane Bonnie came through in 1998.

The controversy spun up by Bertha didn’t end there. Just north of Wrightsville Beach, the storm also eroded 50 feet of beach on the south end of Mason Inlet, which left a condominium resort precariously close to the water. After additional scouring by Floyd in 1999 and a legal battle over whether a sea wall could be built to protect the properties, the inlet was eventually filled in and relocated farther north.

Bertha’s Legacy

While Bertha is often discussed in the context of other storms, especially Fran, its impacts are impressive enough by themselves. The storm’s cost in North Carolina was estimated at $400 million in damage, adjusted for inflation, and that total doesn’t include lost tourism revenues in the months that followed. Twelve total deaths are attributed to Bertha, including two in North Carolina: one in a car accident and one from drowning due to rip currents.

After Bertha moved out of North Carolina, it tracked up the eastern seaboard, maintaining tropical storm strength as far north as Maine. The rain and gusty winds caused flooding and downed trees across the mid-Atlantic states and New England.

Despite the damage, the name “Bertha” was not retired by the World Meteorological Organization, which reserves retirement for storms “so deadly or costly that the future use of its name on a different storm would be inappropriate for reasons of sensitivity”. Three storms from the 1996 season did have their names retired: Fran, Cesar, and Hortense. The latter two were both less costly but more deadly than Bertha.

Of course, many coastal North Carolina residents might argue that the damage from Bertha rivaled that of many destructive storms from the past, and they’d probably rather not see that name appear again. After all, it’s a reminder of the summer when the seeming safety from tropical storms was shattered.

Sources:

- Preliminary Report for Hurricane Bertha by Miles B. Lawrence, National Hurricane Center

- Hurricane Bertha: July 12, 1996 by Tim Armstrong, NWS Wilmington