This post is part of our year-long series about North Carolina’s weather extremes.

An old adage says that March comes in like a lion and goes out like a lamb. But what about the middle of the month? It’s often in between our big winter weather events and our springtime severe weather events. However, in mid-March of 1993, both seasons converged along the U.S. east coast in a storm so colossal and impactful that it’s now called the “Storm of the Century”.

The Building Storm

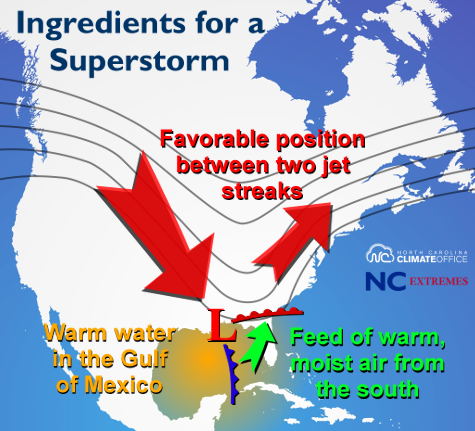

The storm began like many that affect North Carolina: as a weak low pressure system in the Gulf of Mexico on Friday morning, March 12th. The waters of the Gulf were particularly warm for that time of year, which allowed the storm to begin strengthening and organizing, and a southerly flow provided a continuous feed of moisture as the low moved east.

In the upper levels of the atmosphere, conditions were also ideal for rapid strengthening. A trough in the jet stream was digging to the south, with so-called “jet streaks” — areas of locally high wind speeds — just ahead of and behind the developing surface low.

The low sat in a unique position compared to these jet streaks. It was in the left exit region of the trailing jet streak and the right entrance region of the leading one. Both are regions of strong upper-level divergence, where air spreads apart. To replace that air diverging in the upper levels, air must rise from the surface, which means lower pressure and rising motion — both of which help storms to strengthen.

By the morning of March 13th — less than 24 hours after beginning its development over the Gulf — the low had a minimum central pressure of about 970 millibars, comparable to what we see in many category-two hurricanes.

At the same time, the storm was energized even further as two areas of upper-level vorticity, or spin in the atmosphere, merged together. The storm continued to strengthen as a cutoff upper-level low developed and the system took on a comma-shaped appearance on satellite imagery — a classic sign of an intense cyclone.

The surface and upper-level lows were strong and getting stronger. Reinforcements were coming from the infusion of upper-level energy. And at the surface, warm, moist air continued to push in next to cool, dry air to the north and west. All the ingredients were in place for a monster storm along the east coast.

The Storm’s Impacts

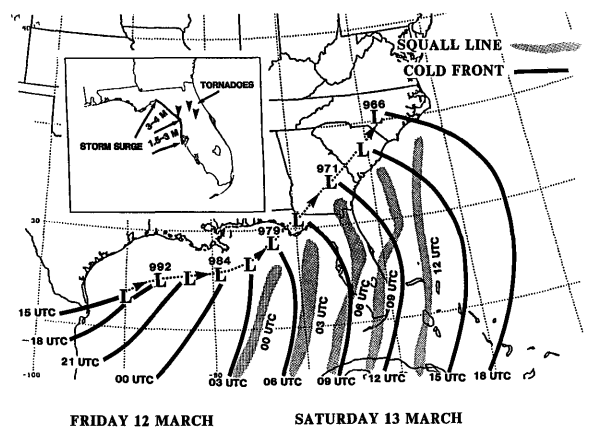

As the surface low and associated cold front approached Florida early on Saturday, March 13th, it brought up to a 12-foot storm surge and a squall line that spawned 11 tornadoes. As cold air pushed southward, parts of the Florida panhandle saw several inches of snow.

The storm continued to strengthen as it moved over the coast of Georgia and the Carolinas. By Saturday evening, the low pressure center sat near the North Carolina/Virginia border with a minimum pressure of 960 millibars.

In February, we discussed why our high pressure records occur during the winter. However, this event brought impressive low pressure readings across the state. Sea level pressure values in Raleigh plunged as low as 968.8 mb, or 28.61 inches of mercury. That’s even lower than the 974.9 mb observed when the remnants of Hurricane Hazel moved through in 1954.

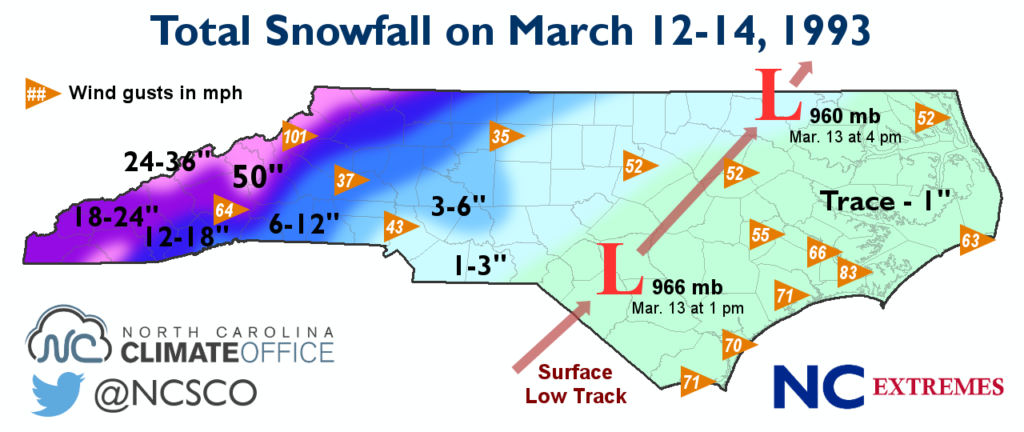

Such low pressure also meant high winds. A 101 mph wind gust was observed on Flattop Mountain near Boone, and Asheville reported gusts as high as 64 mph. Along the coast, near-hurricane force winds were observed, including a 70 mph gust in Wilmington and an 83 mph gust at Cherry Point.

The rush of warm air from the south meant precipitation began as rain everywhere except for the mountains on Friday night and Saturday morning. It transitioned to freezing rain and snow in Greensboro and Charlotte by 2 pm on Saturday, with Raleigh switching over by 6 o’clock. The immediate coast finished with a couple hours of light snow on Saturday night, yielding trace accumulations.

Most Piedmont sites saw one to three inches of snow. In the mountains, snow totals were much more impressive: 18.2 inches in Asheville, two feet in Jefferson, 30 inches at Boone and Banner Elk, three feet at Blowing Rock. The snowfall at many of these and other sites set new daily and storm total records. But more impressive still were the record-setting snow amounts more than 6,200 feet up on Mount Mitchell.

Snowfall Records

Snow began falling on Mount Mitchell early on the 12th, with an inch of new accumulation reported at 3 pm. Over the next 24 hours, 36 inches — yes, three feet — of snow fell, setting the statewide record for the most snow in a 24-hour period. In the following 24 hours, another 13 inches fell, bringing the storm total snowfall to 50 inches — also a statewide record.

Just for some perspective, that was more than half of Mitchell’s annual average snowfall of 92.3 inches falling in less than 72 hours. Another storm in early April brought 18 additional inches of snow, with a season total snowfall of 127.5 inches.

Just over the North Carolina/Tennessee border, Mount Leconte received 60 inches of snow during the event. As the storm continued up the east coast, it brought a widespread foot or more to the Appalachians and New England. The National Weather Service noted that “the areal coverage of snowfall was among the largest of any storm in recorded history”, and added together, the total snow volume was almost 13 cubic miles.

A Lasting Legacy

Rare is a storm with as varied and widespread impacts as this one — from tornado-spawning thunderstorms to feet of snow — so its nickname of the Storm of the Century is quite appropriate. The storm also had an immense human impact: nearly 300 fatalities and almost $9 billion in damage, adjusted for inflation.

Despite the losses, the storm is considered a forecasting success. In early March, computer models began hinting at the threat of a major storm, and the National Weather Service issued blizzard warnings two days ahead of time to prepare a population of more than 100 million people.

Since 1993, the models, forecasts, and our confidence in them have continued to improve, and we can track similar storms well ahead of time. But few storms since then have quite matched the incredible size and severity of the Storm of the Century.

Sources:

- Superstorm of 1993 by Tim Armstrong, NWS Wilmington (2013)

- Overview of the 12-14 March 1993 Superstorm by Kocin et al. (1995)

- A Diagnostic Analysis of the Superstorm of March 1993 by Huo, Zhang, and Gyakum (1994)

- March 12-13, 1993 Derecho by Corfidi, Evans, and Johns, Storm Prediction Center