It began in the wake of extreme flooding from Hurricane Helene and ended amid the onset of sunny summer weather. After spanning parts of all four seasons and all corners of the state at its peak, our latest drought in North Carolina is finally over.

This week’s US Drought Monitor shows that the final sliver of Moderate Drought – or D1, the lowest of four drought categories on their classification scheme – along with all Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions around the Albemarle Sound have been erased after local rainfall totals of more than 5 inches last week.

Almost eight months after drought first emerged in that same northeastern corner of the state, it is finally gone, and the impacts it brought will be both a reminder of this persistent dry spell and a sign of what to expect in years to come.

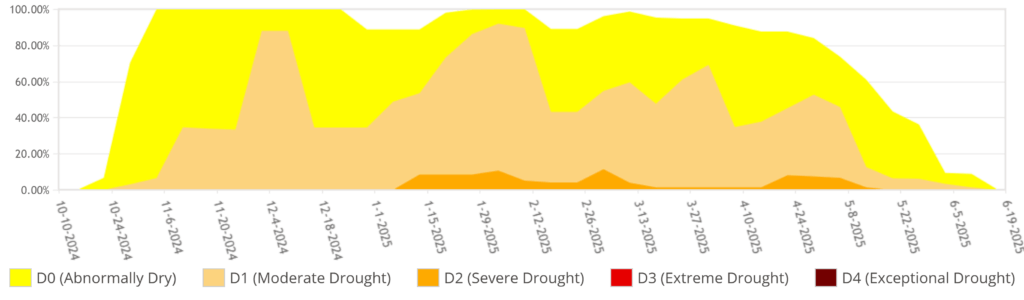

Drought Progression

This drought’s origins were the calm after a storm. Following the heavy rain and flooding from Hurricane Helene late last September, we entered a much drier pattern, with our 3rd-driest October on record statewide since 1895.

Drought first took root in those eastern areas farthest from Helene’s impact, but by early December, the hardest-hit areas in western North Carolina were also in Moderate Drought as part of an extreme wet-to-dry swing for that region.

The La Niña pattern in place throughout the winter helped keep us warmer and drier than normal overall, and even during a cold and snowy January, our liquid precipitation totals were limited, which led to the onset of Severe Drought (D2) in some spots.

At its greatest extent in early February, drought covered 92% of the state in all but parts of the Foothills. Those areas were still feeling the effects as several large wildfires ignited in Helene-damaged parts of McDowell County.

Better rainfall totals in northern and western areas by mid-February helped alleviate some impacts. However, drought’s epicenter then shifted to our southern coastline, where areas such as Wilmington had added another five inches to their ongoing deficits during the winter with only half of their normal precipitation for the season.

A warm, dry March with less than an inch of rain all month in some spots helped drought expand westward once again. That kicked the spring fire season into high gear, which warranted the implementation of a statewide burn ban for the first time since November 2021.

April was also dry and saw delayed crop planting in some areas, but as vegetation greened up, fire activity finally wound down. By May, a more active weather pattern set in with frequent showers and thunderstorms, and that helped erase drought conditions from west to east.

The first half of June stayed cloudy and rainy, which led to the drought’s eventual ending. As of June 18, it’s on pace to be the wettest June on record in Elizabeth City and the 3rd-wettest June in Greenville, where a more than 7-inch rainfall deficit dating back to the fall as of late April has now switched to a surplus after last weekend’s locally heavy rains.

Key Impacts

With its emergence during our cool season over the fall and winter, we largely avoided impacts to water supplies. A few local water systems, such as the City of Statesville, recommended outdoor water use restrictions this spring, but absent the evaporation and higher demands that we see during our summer months, most reservoirs kept sufficient supplies throughout the drought.

Coastal groundwater levels declined last fall and saw less recovery than we’d hoped for this winter, but the recent rounds of rainfall finally brought the needed recharge, with the USGS well in Washington County hitting above-normal levels this week.

Farmers were also largely spared the worst impacts from this drought, which began near or after the end of the 2024 growing season. While that slowed planting of some winter cover crops and some corn and tobacco back in April, by this point, planting has largely caught up to the five-year average pace thanks to the recent rainfall.

By far the most notable impact of this drought was ramping up wildfire activity. Between January 1 and June 18, a total of 3,834 wildfires burned 27,387 acres on state and private lands, according to preliminary data from NC Forest Service. That’s the second-most fires through this point in a year since 2012, behind only the start to 2022 that also included an active spring fire season amid an ongoing drought.

Jamie Dunbar, the Fire Environment Staff Forester at NC Forest Service, and the agency’s three regional foresters in the Mountains, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain recently shared some thoughts about this spring fire season with the State Climate Office. They noted the increased wildfire activity so far this year was a result of several factors, beginning with the drought.

“Although Mountain and Foothill areas weren’t in ‘classic’ drought, we did have dry air and dry surface fuels,” they said, noting that soil moisture was never as depleted as in most summer and fall droughts. In addition, the Keetch Byram Drought Index – a common indicator of the difficulty in mopping up from fires – was generally low except in some coastal areas, where fires burned into highly organic soils like on the Croatan National Forest and in eastern Brunswick County this spring.

However, dryness was still present coming out of the winter, especially in dormant dead fuels such as leaf litter and deciduous shrubs that burned readily during several March wildfire outbreaks. In addition, live fuels such as mountain laurel, rhododendron, and pine trees had low moisture levels, making them very flashy and flammable.

Weather conditions also aligned on several occasions to amplify the fire danger – at times, hitting the maximum Extreme level on the Adjective Rating scale. Spring frontal passages brought gusty winds and dry air masses that initiated “extended periods of time with little to no nighttime relative humidity recovery,” per the NC Forest Service staff, especially in higher-elevation thermal belts in the Mountains and Foothills.

And for those western areas, the damage and debris from Hurricane Helene literally added fuel to the fires. Wind-blown fuels such as leaves, pine needles, and smaller branches ramped up the intensity of these fires, to the point that NC Forest Service “personnel saw trees upwind on the other side of the fire line or road catch fire due to how intense the wildfire was across the line.”

Larger fuels, especially entire trees that were toppled by Helene’s hurricane-force winds across an estimated 822,000 acres, have also presented a challenge in blocking access to storm-damaged areas. This made containing fires on already-rugged landscapes, such as a trio of Polk County fires on steep terrain in March, even more difficult.

Several fires, including those Polk County blazes, the Crooked Creek fire from McDowell County in January, and a 1,000+ acre fire in Swain County in March, prompted local evacuations as strong winds led to a rapid spread across a dry, debris-loaded environment. For folks in those areas still recovering from Helene, it made the dangers of drought hit close to home.

This Drought, in Perspective

Between October 29 and June 10, part of North Carolina was classified in drought for 33 consecutive weeks. That makes this our state’s sixth-longest drought since the launch of the US Drought Monitor in 2000, and the longest since another fall-emerging drought in 2021-22 that also peaked at the Severe Drought level.

During that time, we had seven consecutive drier-than-normal months statewide – between October and April – which was the longest streak since the 2007-09 event that reached Exceptional Drought (D4) levels across the state.

Locally, this drought included the record driest October for Fayetteville, with only 0.01 inches of rain at the airport all month; the record driest winter in New Bern dating back to 1948; and the driest March on record in Danbury since 1947.

| Rank | Consecutive Weeks with Drought in NC | First Week | Last Week |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 155† | Jan. 4, 2000 | Dec. 17, 2002 |

| 2 | 117 | Feb. 13, 2007 | May 5, 2009 |

| 3 | 100 | Jul. 6, 2010 | May 29, 2012 |

| 4 | 53 | May 3, 2016 | May 2, 2017 |

| 5 | 43 | Oct. 26, 2021 | Aug. 16, 2022 |

| 6 | 33 | Oct. 29, 2024 | June 10, 2025 |

| 7 | 31 | Feb. 21, 2006 | Sep. 19, 2006 |

| 8 | 25 | Nov. 6, 2012 | Apr. 23, 2013 |

| 9 | 24 | Aug. 15, 2023 | Jan. 23, 2024 |

| 10 | 23 | Oct. 10, 2017 | Mar. 13, 2018 |

†: This count starts when the US Drought Monitor’s official archive began in January 2000

With the end of the drought, we find a bit of good, bad, and ugly.

The good news is that a long-running drought is over, and we’re in great shape for this point in the summer, with solid soil moisture reserves and lake levels remaining at or above normal. Farmers should also be much happier with the state of their crops compared to this time last year.

The bad news is that we’re about to enter our first heat wave of the year, with high temperatures forecasted in the mid to upper 90s through the middle of next week. That will increase the stress especially on lawns, gardens, and crops, and any areas that miss out on rain showers over the next week or two could see dry weather or drought impacts return.

The ugly is that the extensive tree damage from Hurricane Helene in western North Carolina isn’t going anywhere, and its impacts on amplifying our fire seasons will continue for years to come. Stay tuned to the Climate Blog in the coming weeks for a deeper dive into how this debris is shaping our state’s fire management and preparedness.

For now, we can take a collective breath as the state hits a drought-free milestone, but with heat on the way and the first storms of this hurricane season not far off on the horizon, it’s only a matter of time before our next weather hazards arrive.