August in North Carolina began and ended with rain from tropical systems, and there was plenty of rain in between as well. Temperatures remained warmer as we closed out a warm, wet summer that was noteworthy for a few reasons.

Widespread Wet Weather

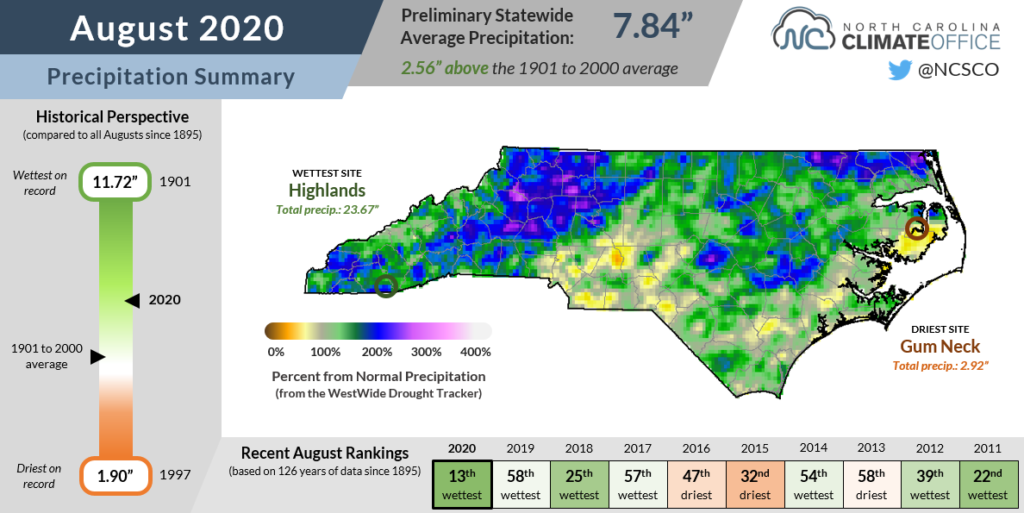

North Carolina took a soaking throughout August, accumulating a statewide average precipitation of 7.84 inches, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). It was our 13th-wettest August since 1895, and the wettest since 1992.

The month was bookended by tropical systems that brought rain on either end of the state. On August 3, Hurricane Isaias made landfall at the southern coast and left 3 to 4 inches of rain across parts of eastern North Carolina, as well as gusty winds and isolated tornadoes that caused localized damage from our southernmost beaches to the Virginia border.

On the final weekend of the month, the remnants of Hurricane Laura moved through as a strong low-pressure system. The main impacts were across western North Carolina, with up to an inch of rain in Cherokee and winds gusting to 30 mph on Saturday, August 29.

Even ignoring those two storms, it was still an unusually active August in terms of weather systems and rainfall. A stalled frontal boundary lingered across the western Piedmont from August 5 to 9, producing 4.02 inches of rain over a three-day period at our Spindale ECONet station in Rutherford County.

Next, a low-pressure system on August 15 was accompanied by several lines of thunderstorms impacting all three regions of the state. Daily precipitation totaled more than 3 inches on the slopes of Pilot Mountain, in the Triangle suburbs in Clayton, and on the shores at Kill Devil Hills.

Moisture moving in from the south on August 21 to 23 generated heavy rains and flash flooding in the southern Mountains and southwestern Piedmont, including 6.01 inches over three days in Highlands — the wettest spot in the state last month with 23.67 inches of total rainfall. That was the 3rd-wettest August and the 6th-wettest month on record since 1879 at that location.

As the month ended, a final round of slow-moving showers over Wake and Johnston counties on August 31 crested the Neuse River in Smithfield to moderate flood stage. Flood waters swept away a car with two small children inside, and both of their bodies were found this week.

After so many heavy rain events, a number of sites especially in western North Carolina recorded historically wet Augusts, including Hickory (14.63 inches; wettest on record since 1949), North Wilkesboro (13.40 inches; wettest since 1956), and Jefferson (11.45 inches; wettest out of 86 years with observations).

Only a handful of stations, mainly in the Sandhills and central Outer Banks, measured below-normal precipitation for the month, and in those areas, the deficits were minimal. Fayetteville was 1 inch below normal and Ocracoke was 1.5 inches below its normal August precipitation..

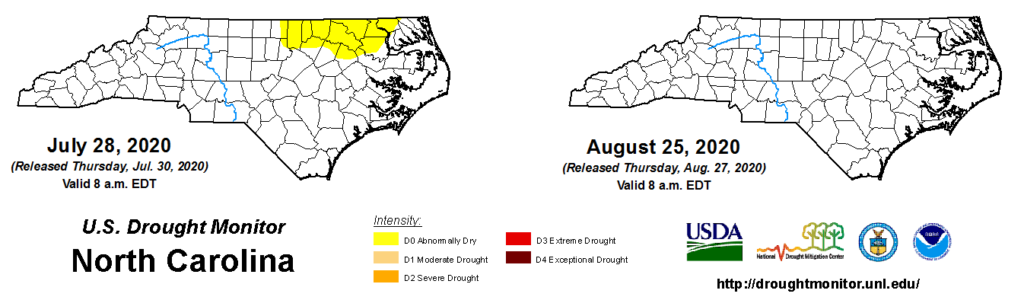

Needless to say, the small area of dryness that emerged across the northern Coastal Plain in late July was no match for the rain from Isaias and other weather systems during August. Monthly average streamflows were near- or above-normal statewide, and soil moisture remains sufficient for crops in most areas as fall harvesting begins.

Hot and Humid Once Again

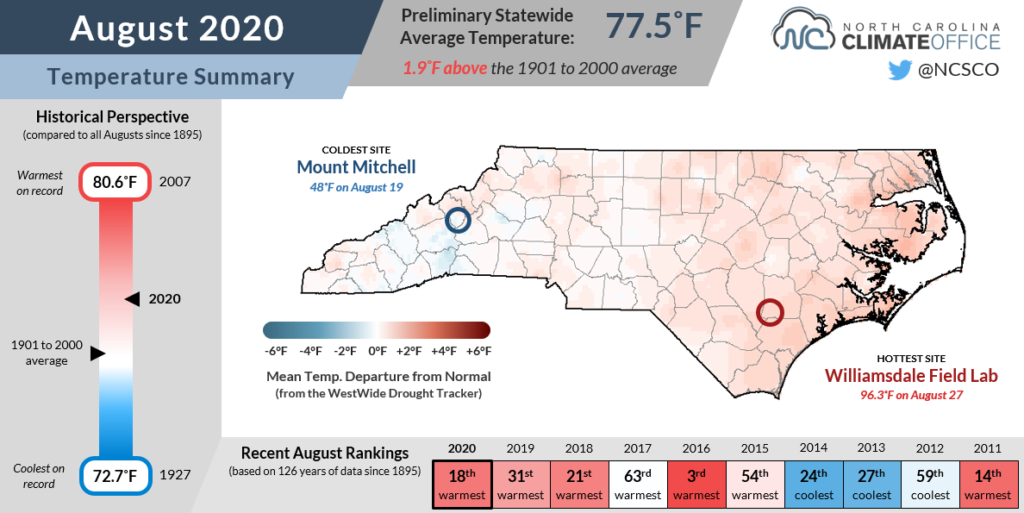

Following our stagnant and steamy July, August remained warm across the state. Per NCEI, the statewide average temperature of 77.5°F ranked as our 18th-warmest August out of the past 126 years, and was 1.9°F above the long-term 1901 to 2000 average.

Some months as wet as August, including our June this year, can be cooler if they have abundant cloud cover or weather systems primarily moving in from the north. In August, though, most of our weather systems came from the south or southwest, circulating along the conveyor-like circumference of the Bermuda high pressure system off the coast.

That tropical air mass continued to support afternoon high temperatures in the 90s along with dew points well into the 70s most days. Instead of the rain providing relief, it just added to the humidity.

Sites along the immediate coast had particularly warm months. On the heels of the warmest month ever recorded at Hatteras in July, it finished with its warmest August and 2nd-warmest all-time month on record with an average temperature of 82.4°F. Elizabeth City also had its warmest August dating back to 1934, and it was tied for the 2nd-warmest August in Wilmington since 1871.

The overnight low temperatures across the state were especially warm last month, in part because of the higher dew points that prevented nighttime temperatures from decreasing as much.

Based on our average minimum temperatures, we were tied for our 2nd-warmest August on record, trailing only 2016. Seven of our eight warmest Augusts based on average lows have happened since 2003.

Summer Summary

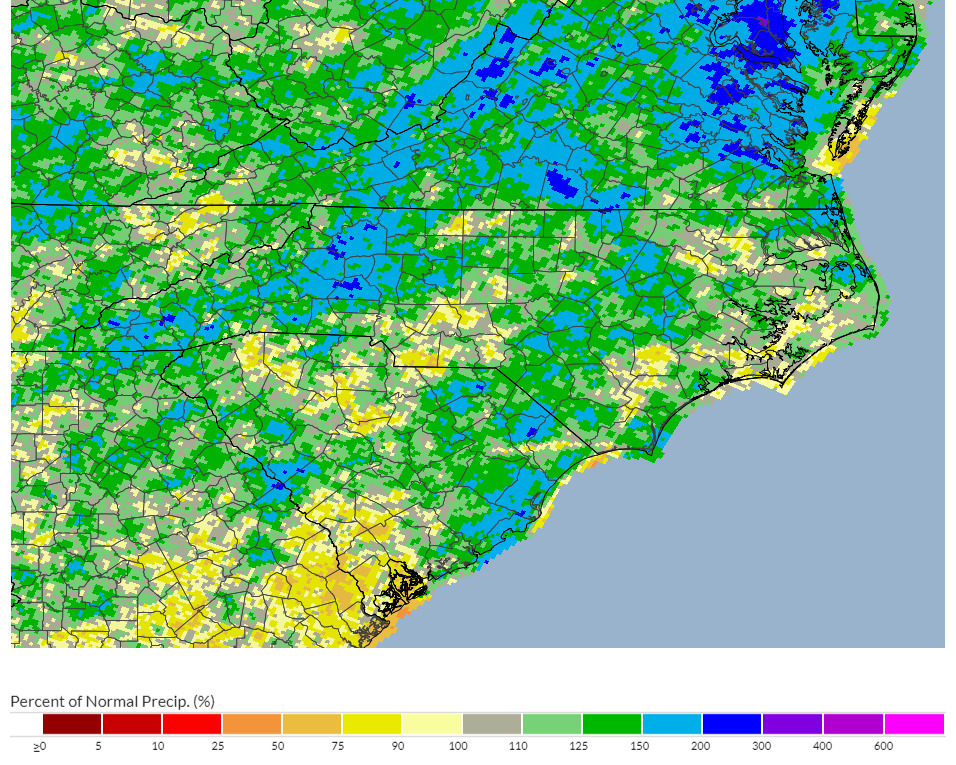

August ended the three-month climatological summer season, and while we did have some month-to-month variations — from a cooler June to a drier July to a wet August — the seasonal rankings show that our summer as whole looked a lot like August, or warm and wet.

The statewide average temperature from June through August of 76.9°F ranked as our 15th-warmest summer on record, while the average precipitation of 17.23 inches made it our 33rd-wettest summer since 1895.

So ten or twenty years from now, what will stand out about this summer, aside from the obvious horror that remembering 2020 will inspire? Here are three main takeaways from the past season:

1. There were some hot days, but with little extreme heat. July in particular was notable for the stranglehold that the Bermuda high had on our state, and some areas set monthly records for the number of days reaching 90 degrees. But despite the warm and often humid weather that extended into August, the heat was rarely oppressive this summer.

Only a few locations in the northern Coastal Plain had temperatures hit the 100-degree mark during the warmest stretch in late July, and in Charlotte, the 41 hours with a heat index of 100°F or greater so far this year is the fewest since 2014. (Of course, that number can still go up in the event of September or even early October heat like we saw last year.)

2. Drought never developed. Due to the typical pop-up, localized nature of our summertime precipitation, at least parts of the state tend to slip into drought at some point just about every summer. So in a summer as warm as this one, seeing no drought at all was quite unusual.

To that end, part of North Carolina had been classified in drought by the US Drought Monitor in 15 of the 20 summers from 2000 through 2019, and three of the five drought-free summers — in 2003, 2013, and 2014 — were cooler than normal. That puts 2020 in rare company over the past two decades, joining only 2017 and 2018 as summers with both above-normal temperatures and no drought.

For avoiding drought so far this year, we can thank our wet spring that kept surface water conditions from declining, our active weather pattern in June and August, and a little help from the tropics. Speaking of which…

3. The tropics sprung to life, and early! It’s usually not until this point in September that we begin seeing multiple tropical storms churning across the Atlantic at the same time. But with warm sea surface temperatures in place and mostly favorable atmospheric conditions over the Atlantic basin this summer, it has been a record-setting hurricane season so far.

Thirteen named storms had formed by the end of August, with the fourteenth and fifteenth — Nana and Omar — developing on September 1. Of those storms, four have directly impacted North Carolina. In May, Arthur and Bertha each brought several inches of rain to parts of the state. In early July, Tropical Storm Fay formed just offshore and produced some rain along the southern coast. And, of course, Isaias made landfall and crossed the Coastal Plain in early August.

Adding in the remnants of Laura late last month, it has been an active tropical season already, and North Carolina has been in the crosshairs of several storms. With the climatological peak of the season still ahead, 2020 could match or exceed the activity level of 2005 — the current record-holder with 27 named storms, including the final six named after letters of the Greek alphabet.

With that in mind, will 2020 get any worse this fall? At least in the tropics, it might get Beta.