Those warm days in late December when temperatures touched the 70s didn’t just make you pull out the sandals for holiday break. They also helped 2019 secure the title of North Carolina’s warmest year on record.

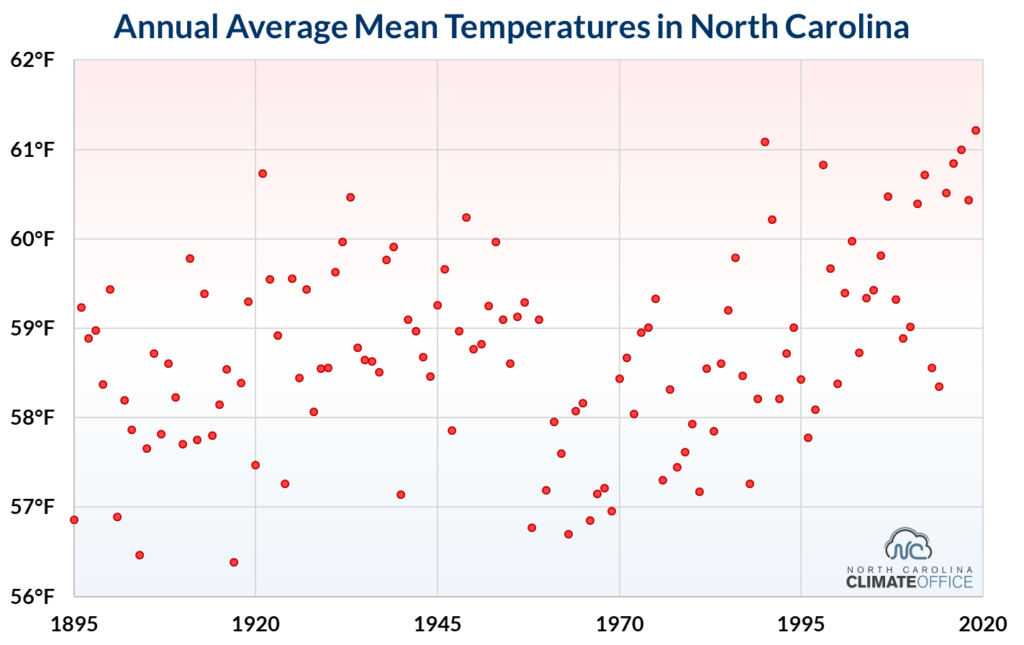

Our record-setting year was confirmed today by our colleagues in Asheville at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information. They calculate national, state-level, and local average temperatures and precipitation using quality-controlled weather station observations interpolated to a 5-kilometer grid. These data date back to 1895.

In other words, it’s our best and most accurate measure of surface weather conditions using on-the-ground monitoring sites, which is a fancy way of saying good old-fashioned thermometers and rain gauges. This tried and true equipment tells us that 2019 consistently moved the mercury higher than any other year observed.

To break down this record and what it means, here are the answers to some common questions about last year’s warmth in North Carolina.

How Did It Happen?

In short, it was a year in which our temperatures were generally temperate and our prevailing air masses were typically tropical. Just two months all year — March and November — had below-normal statewide average temperatures, while three others — May, September, and October — all ranked among the top-five warmest.

That early-summer onset and early-fall persistence of heat and humidity were ultimately among the most memorable parts of the year, and they helped make it such a warm one.

We talked throughout the summer about that stubborn subtropical high pressure system that made our weather so hot and humid, but as early in the year as February, we noted that similar weather systems had set up off our coast and given us a warm finish to the winter.

By the end of October, our year-to-date average temperature was just ahead of 1990 — the previous record-holder. While a cooler November put us behind record pace, our 17th-warmest December on record, which included those 70-degree days in the week before New Year’s Eve, put us back in the top ranking.

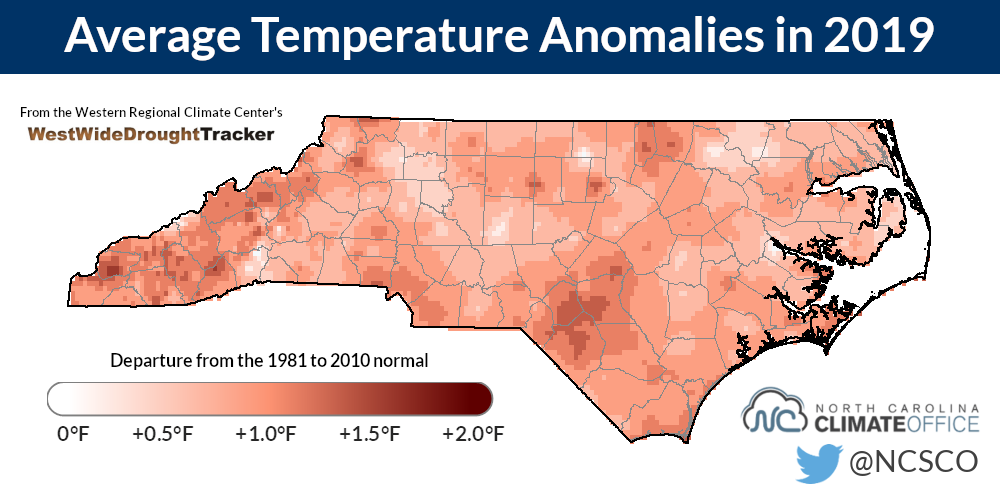

The statewide average mean temperature of 61.22°F last year edged out the 61.08°F average from 1990, but crucially, it was 2.7 degrees warmer than the 1901 to 2000 average temperature of 58.5°F.

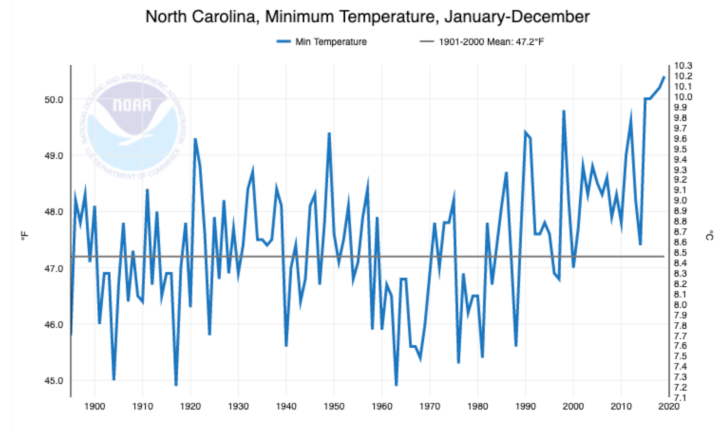

And it wasn’t just our mean temperatures. It was also our record warmest year based on average minimum temperatures — each of those top-five warmest years have come in the past five years — and our fifth-warmest year based on average maximum temperatures.

That inevitably invites discussion of the question we’ve been asked many times: is this climate change?

Is There a Warming Trend in North Carolina?

In the past 30 years, North Carolina has recorded each of its five warmest years on record — 2019, 1990, 2017, 2016, and 1998 — along with ten of its 30 warmest years.

Over that same time, we have recorded zero of our 30 coolest years on record. The last time that happened was in 1988 — our 15th-coolest year — when Phil Collins was on top of the Billboard pop charts and the elder George Bush had just won the White House.

The 80s was also a decade with several extreme cold events, including “the Coldest Day” on January 21, 1985, when many sites set their all-time record lows, and the Christmas blizzard in 1989 at the coast that was followed by sub-zero temperatures.

Similar atmospheric setups such as the one in January 2014 have brought some cold weather, but we haven’t approached those record lows.

In fact, record lows are getting harder to come by. In 2019, 881 daily maximum temperature records were broken or tied across North Carolina, which was almost four times the number of daily minimum temperature records that were broken or tied in the state (156).

That’s another way of showing that it’s been more warm than cool recently, and it’s one sign that North Carolina is experiencing the consequences of a warming planet. Where we are really seeing the heat isn’t necessarily in the daytime temperatures, but the dominant trend is in our nighttime lows. It’s those readings that have consistently pushed some of our recent warm years into the top ten.

It’s not just because of urban heat, or the effect that keeps cities warmer than their surrounding rural areas overnight. It’s that the climate system is just more sensitive to warming nighttime temps.

Essentially, it’s easier to heat up the nighttime air than the air in the daytime because there’s less of it. The top of the air mass that is heated is much closer to the surface during the night. This trend is apparent in the graph provided by NOAA’s NCEI in the section below.

What Does This Mean for Future Years?

Even on a warming planet, North Carolina’s climate isn’t a staircase. There’s no guarantee that 2020 will be hotter than 2019. Going forward, we will still see day-to-day, month-to-month, and year-to-year variability in our weather, so not every year will be warmer than the ones before it.

But if you’re a gambler, we’re stacking the deck with more warm daily temperature records than cool ones. And those warm days and nights add up to warm months, which make for warm years.

The obvious consequence is that the bar is set slightly higher — 0.14°F more than the previous record — for future years that may contest the record (and there almost certainly will be more record-breakers, based on future global temperature projections). In North Carolina, the climate is projected to warm anywhere from 4 to 10°F by the end of the century.

However, the background change in our climate due to the addition of heat-trapping gases to the atmosphere over a relatively short time does mean that warmer years are more likely than cooler ones, which is exactly what we’ve seen over the past three decades.

While 0.14°F certainly doesn’t seem like much — for instance, the difference between a 70°F degree day and a 71°F degree day is imperceptible to most humans — but these small changes in these annual averages mean big shifts in our extremes. Our hottest days and nights are getting hotter.

Not every October will feel like August as it did this year, but that is likely to become a more common occurrence, especially as the warmer climate creates more evaporation from the oceans, more condensation in the air, and an overall more tropical environment that may infiltrate our springs and falls.

Likewise, locations like Raleigh — which is already having more intense and longer heatwaves, according to the National Climate Assessment — may see a transition to a warmer climate more similar to Savannah than its historically moderate one in the North Carolina Piedmont.

Why Does It Matter?

Thinking back through 2019, the warmth may have manifested itself as a few more short-sleeve days in February and December, or a bit of extra sweat and sunburn while you waited for fall-like weather to finally arrive.

But these patterns becoming more common in the future will have impacts to more than just your wardrobe.

First and foremost, heat is a human health issue. It is the #1 weather-related killer. And with more extreme temperatures, longer heatwaves, and general socioeconomic disparity, the risk only increases.

More people will be exposed to lethal temperatures. Some of our most sensitive populations in North Carolina lack access to sufficient cooling, or live in urban areas covered in asphalt without access to shade. We have outdoor laborers on our farms and in construction, who may face extreme heat during the day and little relief at night.

Although milder winters and faster-emerging springs could extend the growing season and make our climate more hospitable to crops such as citrus fruits, more intense summer heat will also increase the stress on crops and make year-to-year yields more unpredictable.

Stone fruits will lack the chilling hours, or cooler temperatures, required for their development. That’s not speculation; it’s a phenomenon peach farmers in Georgia are already facing. The things we grow here are accustomed to a specific climate.

With those longer growing seasons and extended warm periods, we could see the emergence of things we don’t want more of — weeds, pests, and invasive species. And looping back to human health, it’s also a more hospitable climate for the bugs that carry vector-borne diseases.

We are moving rapidly into a different North Carolina than the one we used to know. It is one that is warmer, wetter, and generally more prone to extremes — intense daytime heat, hot nights, and heavy downpours.

Many projections agree that while we may see more and heavier rain overall, it may become increasingly distributed in fewer events with bigger gaps between them. While we watch a country burn half a world away from us, it’s a good reminder that drought and wildfire are also part of North Carolina’s climate, and are susceptible to the same growing extremity.

Benchmarks like this record don’t just make for coffee-shop small talk; they’re the evidence in the case pointing to this global phenomenon hitting us here in our backyard. These numbers and records have actual consequences and translate into impacts — to our people and our livelihoods.