The late 1990s in North Carolina became synonymous with names like Bertha, Fran, and Floyd. But another, perhaps less well-remembered hurricane hit the state in the same turbulent four-year period, and in more ways than one, Hurricane Bonnie bridged the gap between North Carolina’s landfalling storms of the era.

Summers of Sea Change

After back-to-back hurricanes — Bertha and Fran — hit North Carolina in the 1996 season, the summer of 1997 brought a welcome relief from tropical activity, at least along the coast.

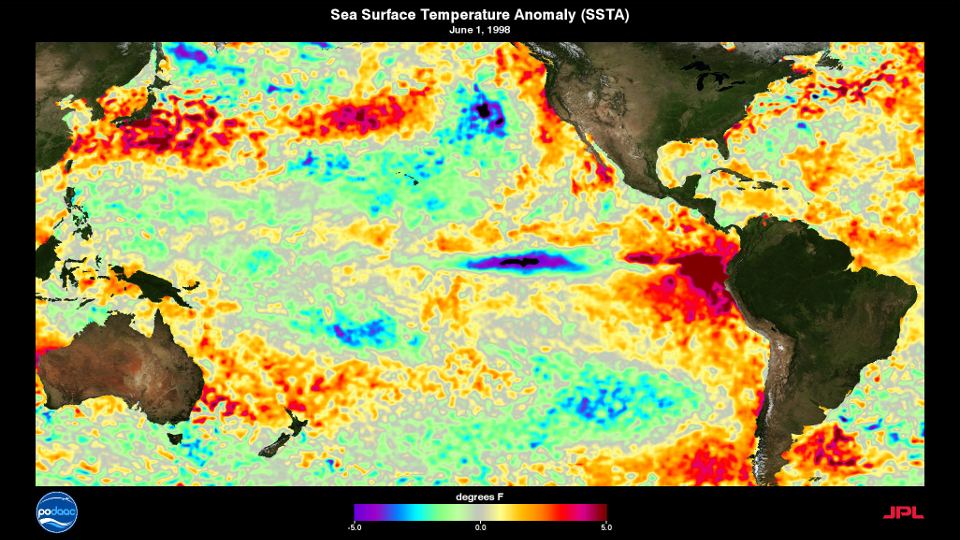

The developing El Niño, which in the winter of 1997-98 would become one of the strongest on record, bolstered the storm-shearing trade winds across the Atlantic and held down tropical activity. Just seven named storms formed, and only one — the remnants of Hurricane Danny — affected North Carolina, bringing some locally heavy rainfall across the Piedmont.

As quickly as we’d entered El Niño that summer, we transitioned to La Niña for the summer of 1998, which became one of the more active Atlantic tropical seasons to date. In total, 14 named storms and 10 hurricanes formed, including Hurricane Mitch — a slow-moving Category 5 storm that devastated parts of Central America.

That active season got off to a relatively quiet start, though. Just one named storm — Tropical Storm Alex — had developed by the middle of August, merely a month from the climatological peak of the season.

However, the next system on deck was about to put the 1998 season on the map, and North Carolina was in its crosshairs.

Storm History

On August 19, 1998, Tropical Depression Two formed from a cluster of consolidating thunderstorms in the central Atlantic. The next day, it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Bonnie as it tracked just north of the Caribbean islands of Antigua and Barbuda.

By the evening of August 21, after Bonnie had passed 125 miles north of Puerto Rico, it reached hurricane strength. While its trajectory showed Bonnie was headed toward Florida, a weakening ridge to the north helped turn the storm northwestward.

Forecast models initially overdid this turn and expected the storm to curve back out to sea. However, they eventually came into relative agreement that Bonnie would likely make contact with the North Carolina coastline.

Some of North Carolina’s most famous landfalling storms have seen their intensity wildly fluctuate as they headed toward the state. Isabel, for instance, suddenly weakened from a Category 4 to a Category 2 in the days before it hit the Outer Banks, while Bertha gained strength in the 24 hours before it made landfall.

By contrast, Bonnie was remarkably consistent, remaining at Category-3 intensity with maximum sustained winds of 115 mph for 78 consecutive hours, or 14 of the National Hurricane Center’s six-hourly advisories in a row. Only in the final hours before landfall did Bonnie weaken slightly.

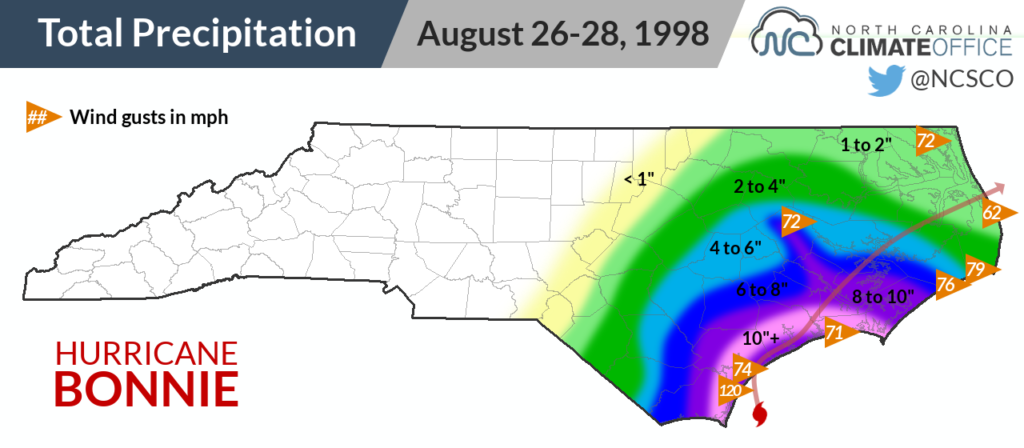

On the evening of Wednesday, August 26, Bonnie made landfall north of Wilmington in Pender County. At the time, the storm was classified as a strong Category-2 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 109 mph.

At Wrightsville Beach, winds gusted as high as 115 mph during the rain bands before the eye arrived, and at the State Port Office in Wilmington, a gust of 120 mph was reported at 9:38 pm, just as the eye moved onshore.

Assessing the Damage

Compared to Bertha and Fran, Bonnie’s impacts on the state appeared to be milder than anticipated. Yes, some homes, businesses, and piers did sustain damage, but overall, it seemed that the coast made it through relatively unscathed.

“Fran was a big, terrible bulldog compared to what Bonnie is,” said pastor Don Horn, whose Surf City Church suffered only minor damage. “Bonnie was just like a little kitty cat.”

So why weren’t Bonnie’s effects along the coast as bad as expected?

It was partially due to the storm’s track. Bonnie curved sharply to the northeast after it made landfall, which largely kept the damaging right-front quadrant — where the storm’s forward motion adds an extra punch to its counterclockwise wind field — out at sea instead of over land.

While the storm did bring some typical tropical impacts, including downed trees and power lines that left 800,000 customers without power in eastern North Carolina, the state was largely absent of any of the scenes of total devastation that accompanied other storms of the era.

Even in some of the worst-affected coastal areas such as Topsail Island, where roughly 600 homes suffered damage, the impact was somewhat muted. And that wasn’t a coincidence. Lessons learned from Bertha and Fran also helped those places better withstand Bonnie.

The town of North Topsail Beach was shielded from more extensive damage by protective dunes built after Fran, even though some of them were breached by Bonnie. Many homes on Wrightsville Beach that were destroyed by Fran were re-built to be more storm-proof as part of a FEMA pilot program, and they survived Bonnie in tact.

Bogue Banks, which includes towns such as Atlantic Beach and Emerald Isle, were also better protected from Bonnie by an artificial reef of tires, many of which washed ashore during the storm. Of course, that was a better outcome than if the storm surge had penetrated inland and swept the remains of homes and businesses out to sea.

During the 48 hours in which Bonnie crept along the coastline, the storm did bring some heavy rainfall, peaking at 14.61 inches just north of Wilmington. But even the potential flooding wasn’t as bad as it otherwise could have been since the eastern part of the state was in a drought when the storm hit.

Wilmington, for instance, had been mired in its 10th-driest summer on record, with seasonal precipitation more than 7 inches below normal. Bonnie single-handedly eliminated that deficit in the final days of the meteorological summer.

Flooding mainly occurred in the usual vulnerable spots — low-lying areas and along the Outer Banks, where the storm surge on top of the existing tide flooded Highway 12.

The greatest damage in North Carolina may have been to the agriculture industry. Between fields soaked by several days of persistent rains and wind-whipped tobacco, corn, cotton, and soybean crops, losses were significant in parts of the southern and central Coastal Plain, especially in Columbus, Jones, and Sampson counties.

“You fly along and don’t see much damage to the beach houses, and it’s easy to think we didn’t have much damage,” said Jim Hunt, the then-governor in an interview with the Associated Press. “But then you look at the tobacco in fields and you know the damage has been extensive.”

Under the Radar

Bonnie represented an interesting transition between its predecessors Bertha and Fran, which wreaked havoc along the coast, and its successor Floyd, which became the costliest storm in the state’s history primarily because of its effects farther inland.

Perhaps its juxtaposition between those storms means Bonnie has become an underestimated storm, or even one lost in history’s shuffle. However, the statistics show it ranked highly by almost every metric.

Bonnie’s property damage bill in North Carolina was estimated at $240 million, with an additional $164 million in crop damage. Adjusted for inflation, the total damages equate to more than half a billion dollars, which ranked 8th in our list of North Carolina’s costliest storms from 2015. Since then, it has been bumped down that list by Hurricane Matthew, which North Carolina Emergency Management estimated had damages totaling $4.8 billion.

| Storm | Year | Maximum Sustained Wind Speed at Landfall |

|---|---|---|

| Hazel | 1954 | 132 mph (Category 4) |

| “San Ciriaco” | 1899 | 121 mph (Category 3) |

| “Great Beaufort” | 1879 | 115 mph (Category 3) |

| Fran | 1996 | 115 mph (Category 3) |

| Bonnie | 1998 | 109 mph (Category 2) |

In terms of sustained wind speeds at landfall, Bonnie was the fifth-strongest storm on record to directly hit North Carolina — more intense even than Bertha, Floyd, and Isabel, each of which had maximum sustained winds estimated at 104 mph at landfall.

The one category in which Bonnie fortunately didn’t rank highly was fatalities. The storm caused one death in North Carolina when a tree fell on a house in Currituck County, killing a 12-year old girl inside. Two additional deaths in Delaware and Massachusetts are attributed to the storm.

Following the active 1998 Atlantic hurricane season, two storm names — Georges and Mitch — were retired by the World Meteorological Organization. In perhaps another case of history overlooking Bonnie, it was not removed from circulation, so we’ve seen additional incarnations of Bonnie — all at tropical storm strength — in 2004, 2010, and 2016.

If nothing else, seeing that name return every six years serves as a reminder of the storm that hit North Carolina in 1998, sometimes obscured amid one of our stormiest stretches in history, but with the strength and sting to stand out as one of the most robust storms to strike our state.

Sources:

- Hurricane Bonnie Preliminary Report by Lixion A. Avila, National Hurricane Center

- North Carolina’s Hurricane History, Fourth Edition by Jay Barnes

- Hurricane Bonnie: August 27, 1998 by the National Weather Service in Newport/Morehead City

- East Coast may be spared hit from Hurricane Danielle from CNN

- Stormproof Houses Survive Hurricane Bonnie from WRAL