Before Fran, Floyd, Isabel, or Irene, there was Hazel.

When Hurricane Hazel made landfall 60 years ago today, it set the standard for hurricane intensity and destruction in North Carolina. In our state alone, the storm destroyed more than 15,000 buildings, left 19 people dead and 200 injured, and caused nearly $1.2 billion in damage, adjusted for inflation.

Hazel’s fury was due to at least four factors that combined to make it a “perfect storm”, in a way, for North Carolina:

1. Category-Four Winds

Although many storms weaken as they approach the coast, Hazel gained strength in the hours before landfall. As its eye came ashore near the North Carolina/South Carolina border, Hazel was at category-four strength with winds exceeding 130 mph. From Myrtle Beach through Cape Fear — at Ocean Isle, Holden Beach, and Oak Island — wind speeds were estimated as high as 150 mph.

Few structures could withstand winds that strong. One report noted that “every pier in a distance of 170 miles of coastline was demolished and whole lines of beach homes literally disappeared.”

2. A Fast Forward Speed

Hazel’s stay in North Carolina was brief. After making landfall around 9 a.m. on the 15th, the eye needed less than four hours to complete its northward trek through the state, moving at a speed of up to 60 mph. For the eastern part of the state, the forward speed added to the storm’s strong winds meant an extra punch from the storm.

Goldsboro and Kinston had estimated winds of 120 mph, and Raleigh and Fayetteville each felt hurricane-force winds despite being nearly a hundred miles inland. There was widespread wind damage, with the U.S. Weather Bureau suggesting that “an estimated one-third of all buildings east of the 80th meridian [which runs just east of Winston-Salem and Charlotte] received some damage.”

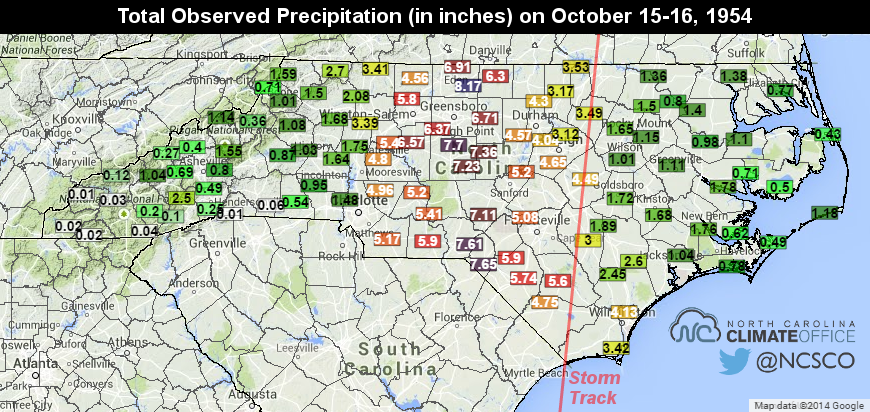

3. Heavy Rainfall

As Hazel moved inland, it interacted with a cold front approaching from the west and transitioned from a tropical system to an intense extratropical cyclone. Storms undergoing an extratropical transition often have precipitation spreading to the north and west, similar to what we saw as Irene moved northward in 2011.

Hazel underwent a similar evolution, with heavy rain falling west of the eye’s track in a short period of time. Much of the Piedmont received at least five inches of rain, and several sites including Laurinburg, Carthage, and Lexington set daily rainfall records that still stand today. An observer in Forsyth County remembered it as “the heaviest I’ve ever seen it rain; it poured buckets”.

The soaking rains caused crop losses across the state, and the wet ground plus strong winds also meant lots of fallen trees, adding to the damage.

4. A High Tide and a Surging Sea

During October full moon events, the earth’s position between the sun and the moon causes some of the highest tides of the year. In eastern North Carolina, they’re sometimes called the “marsh hen tides” because they flood the low-lying homes of their namesake waterfowl.

The full moon — and the marsh hen tide — of October 1954 came on the 15th: coincidentally, the same date as Hazel’s landfall. That high tide alone would have raised water levels several feet, but when added to the water pushed ashore by the storm’s winds, it created a devastating storm surge of 15 to 18 feet along the southern coast.

The damage was cataclysmic. The U.S. Weather Bureau’s reports from the storm are almost chilling to read: “All traces of civilization on that portion of the immediate waterfront between the state line and Cape Fear were practically annihilated.” Homes became “unrecognizable splinters”, or “simply disappeared”. “In most cases it is impossible to tell where the buildings stood.”

Hazel’s Lasting Legacy

Sixty years later, Hazel sits firmly among our most damaging hurricanes, and it remains the only storm to make landfall at category-four strength in North Carolina. In many ways, its extremity was a consequence of the unforgiving combination of strong winds, rapid forward speed, heavy rain, and storm surge exacerbated by the high lunar tide.

The coast, of course, has recovered since Hazel and weathered the storms since. But it’s tough to imagine the damage a present-day Hazel — with the right recipe of environmental ingredients — might do across the state.

Sources:

- Hurricanes of 1954 by Walter R. Davis, U.S. Weather Bureau

- Climatological Data: October 1954 by the U.S. Weather Bureau