Limited rainfall brought drought back last month, while our temperatures were mostly typical for the first month of fall. Last month had a quiet start but a busy end in the tropics, as we discuss in our hurricane season update.

Note: Due to the federal government shutdown, statewide statistics and rankings from the National Centers for Environmental Information were not available at the time of publication. These will be added to this post, along with the usual summary infographic, as soon as they are available.

Ongoing Dryness Drives Drought’s Return

Continuing a dry pattern that began in August, much of the state again finished below its normal rainfall in September.

Monthly rainfall totals generally declined from west to east. In the Mountains, both Murphy and Marshall finished a few hundredths of an inch below their normal rainfall, and Waynesville finished almost a quarter-inch above normal, with 4.48 inches in total.

Across the Piedmont, Greensboro was only 0.66 inches below normal, Charlotte was exactly 1 inch below normal, and Raleigh was 3.23 inches below normal in its 34th-driest September on record locally.

Several eastern sites had less than an inch of rain all month, including only 0.28 inches in Washington in its driest September on record since 2004 and 0.90 inches in New Bern for its 2nd-driest September. Lumberton had 0.97 inches in its 7th-driest September on record, and the month saw the continuation of a 35-day rain-free streak – the longest dry stretch there since 1953.

While rain was infrequent and not particularly widespread last month, a few heavier events soaked parts of the state throughout September. First, a line of showers in the southwestern Piedmont on September 6 prompted a Flood Advisory in Cleveland County, with several CoCoRaHS observers near Shelby measuring more than 3 inches of rain that day.

An approaching front brought up to 2 inches of rain in the Mountains on September 25, and that same system produced slow-moving rain showers along the Virginia border on September 27 that yielded daily totals of more than 2 inches in spots such as Danbury and Eden. Over a three-day period, W. Kerr Scott Reservoir recorded 3.80 inches, which boosted the lake almost half a foot above its target level.

For parts of our southern coastline, the month ended on a wet note with two days of heavy rain from the fringes of Hurricane Imelda. On September 29, our ECONet station on Bald Head Island reported 3.39 inches – its highest daily total since 12.29 inches on September 16 of last year during Potential Tropical Cyclone Eight.

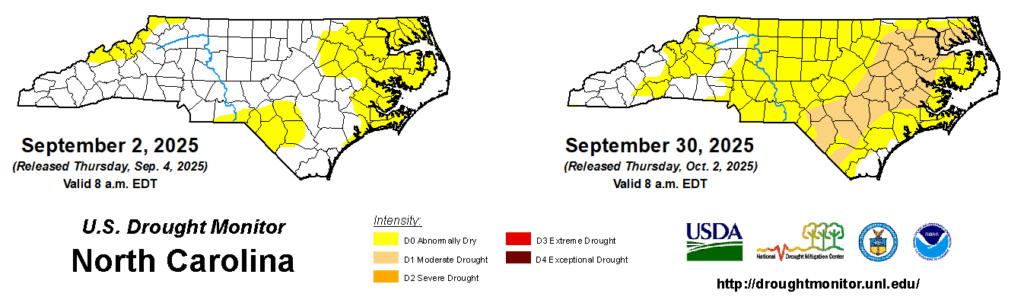

Despite those local rain events, the bigger story last month was emerging dryness and drought. The US Drought Monitor assessment from September 30 shows 58% of the state in Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions and 24%, all in the interior Coastal Plain, in Moderate Drought (D1). That’s our greatest drought coverage since May 6, before spring showers spelled the end of our long-running cool-season drought.

We’re now watching another fall drought develop for the fifth year in a row, and the impacts so far are familiar ones. Streamflow levels have dropped below normal throughout the Tar, Neuse, and lower Cape Fear River watersheds, and soil moisture has declined in that same coastal region, causing stress and stunting for late-planted crops such as cotton and soybeans.

Due to the recent dryness, some trees have started shedding their leaves early to conserve moisture. While we’re not yet in the heart of fall fire season that often aligns with the leaf drop, we did see a few spotty fires last month, including a 132-acre blaze in Bertie County, that could be a sign of things to come this season if we don’t receive more rain soon.

Fall-Like Weather Settles In

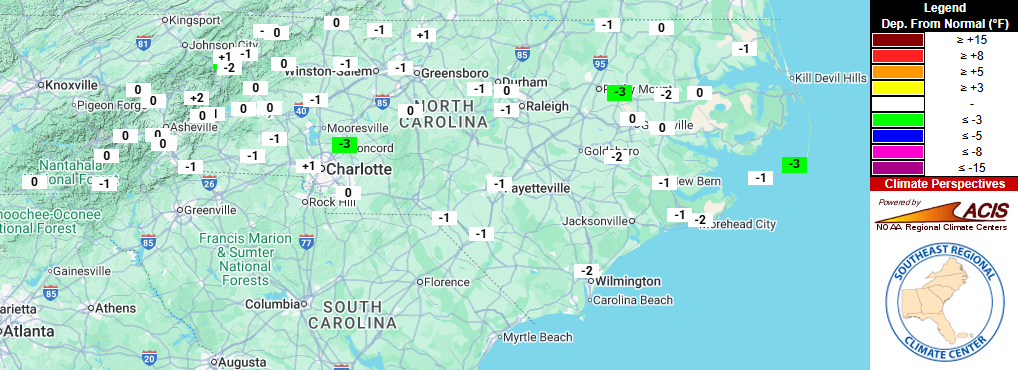

A few hot days were balanced out by more seasonable stretches in September, giving near-normal temperatures on average for the month.

With such typical temperatures for this time of year, most sites finished within a degree of their normal average temperatures for the month. Among long-term observing sites, Asheville, Fayetteville, and Raleigh all matched their normal monthly temperatures, finishing as tied for the 48th-warmest, tied for the 53rd-warmest, and tied for the 59th-warmest September on record at each respective site.

Only a few local stations were exceptions to the near-normal rule last month, finishing with more extreme rankings. In the west, Celo had its 11th-warmest September in the past 63 years, while Hatteras tied for its 43rd-coolest September in the past 131 years, almost three degrees cooler than normal on average.

While the month overall finished near normal, there were some hotter days mixed in. High temperatures reached the low 90s in eastern areas on September 5 to 7, and again by September 20.

The warmest stretch came after the start of astronomical fall, with widespread 90s on September 24 and 25. Charlotte’s high of 91°F on September 24 was its latest 90-degree day since 2019, and Raleigh hit 95°F that same day – the sixth-latest occurrence of such heat there in any year.

Along with those summer-like days, we had several crisp fall nights and mornings throughout the month. On September 9 with high pressure funneling in cold air from the north, low temperatures dropped into the low 40s across the western Piedmont, with 30s at several mountain sites. Statesville had its earliest fall morning in the 40s since 2017, and Boone’s low of 37°F was its earliest reading that cool in a season since 1997.

The month ended with a pair of cooler afternoons, including high temperatures only reaching the upper 60s in parts of the Piedmont on September 29 and 30. In Charlotte, the high of 69°F on September 29 was its coolest September day in almost two years, since September 27, 2023.

Our recent cool days and chilly nights are a sign that the first fall freeze isn’t too far away, barring an overwhelmingly warm fall like we saw last year. Many mountain areas expect their first freeze in the first half of October, while for Piedmont sites, it’s more common by late October or early November.

A Past-the-Peak Tropical Update

The story of this Atlantic hurricane season so far has been fits and starts: clusters of tropical activity, separated by weeks of calm across the basin.

The first three storms, including Chantal, all formed within a two-week span in late June and early July. After that, it took almost a month before we saw the fourth storm, Dexter, followed a week later by the formation of Erin en route to a close call with our coastline.

The sixth named storm, Fernand, developed about a week earlier than the historical average date in late August, so headed into September, it certainly seemed like the pre-season outlooks calling for near- to above-normal activity were right on pace.

But then the Atlantic went quiet once again, and at the time of year when it’s usually the busiest. This was the first time since 2016 with no active storms on September 10, which is the typical peak of hurricane season.

As Colorado State’s forecast team outlined in a discussion last month, a few factors contributed to the lack of storms in early September. Namely, broad high pressure made for a dry, stable air mass across the Atlantic; drier weather over west Africa suppressed the disturbances that tend to develop into storms; and elevated wind shear off our coast prevented any tropical development closer to home.

As it was earlier in the summer, it felt like this lull was only temporary – after all, sea surface temperatures across the main development region have remained much warmer than average, even if not quite at the same record levels of 2023 or 2024.

And sure enough, the formation of Tropical Storm Gabrielle on September 17 kick-started the latest wave of activity, which also included Humberto and Imelda before the end of the month.

With nine named storms so far, we are running slightly behind the normal pace, which sees the eleventh named storm form by October 2, on average. But with lingering warm water and the potential for slightly more favorable upper-level wind conditions due to the developing La Niña, the end of this hurricane season could stay active.

Similar ingredients were in place in 2022, when five named storms formed in October and November, including Nicole – the remnants of which helped alleviate drought conditions in western North Carolina. Likewise, last year saw five tropical storms form in a four-week span between mid-October and mid-November.

For areas in need of rain to push back against this year’s developing drought, the tropics could still offer some hope this fall. And for a state barely one year removed from Helene and just three months past Chantal’s soaking, we can’t let our guard down just yet in this temperamental tropical season.