It started with something familiar, at least by our wintry weather standards in North Carolina. But it didn’t take long to turn into a winter storm like the Triangle area had never seen before.

On the evening of January 24, 2000 – a Monday, although that hardly mattered in the storm that warped time by putting normal life on pause for more than a week – precipitation began falling as sleet. That noisy nuisance is a mainstay of our wintry events: a sign of just enough warm air aloft that falling snowflakes melt before refreezing into ice pellets in the cold air near the ground.

Rod Gonski, the now-retired former lead forecaster at the National Weather Service office in Raleigh, heard the sleet at his house that evening, several hours before he was due to start a midnight shift tracking what was expected to be a run-of-the-mill minor snow event, with forecasts calling for 1 to 3 inches in Raleigh.

“Looking outside and seeing the heavy fall of sleet, I couldn’t help but want to get in very quickly to try to see what was going on,” said Gonski in a recorded interview several years ago. “I drove through heavy sleet, which was transitioning to snow as I came in, and later on, I found out the snow was coming down at a rate of about four inches per hour.”

Dr. Gary Lackmann, a meteorology professor at NC State who arrived in North Carolina in 1999 after stints in snowier climates such as Montreal and Rochester, also noticed the sleet with a few big snowflakes mixed in, which was a novelty in a new state.

“I woke my wife up to tell her it had changed to snow,” Lackmann said recently while remembering the event. “That was not a smart move; she said ‘let me sleep and I’ll see how much it snowed in the morning’.”

The answer she woke up to was an incredible 20 inches or more on the ground. It was a surprise to even the forecasters and weather experts, not to mention the general public that was suddenly snowed in across Wake County and surrounding areas.

The story of how so much snow snuck up on us, and how it paralyzed parts of the Piedmont for almost two weeks, is one of meteorological mystery, failed forecasts, societal strain, and local legend.

A Snowy Surprise

That blockbuster storm wasn’t the only wintry event in January 2000. During a cold two-week stretch to end the month, snow fell across parts of the state on the 17th and 18th, the 19th and 20th, and the 22nd and 23rd, eventually concluding with a snowy and icy mix on the 29th and 30th.

The storm on the 24th and 25th was initially expected to fit the mold of many of our typical snow events, with a low-pressure system developing over the Gulf of Mexico and moving up the Atlantic coast. Given this storm’s offshore track, the bulk of the moisture – and the extent of any snow – would likely be confined to eastern North Carolina.

The modest snowfall forecast wasn’t lost on Ken Hisler, who joined the City of Raleigh’s staff in 1999 as a gardener, helping with landscaping and horticultural work, including the floral displays in highway medians.

“I grew up outside of Philadelphia in Delaware, so three inches didn’t seem like that big of a deal,” said Hisler, now the assistant director of the Raleigh Parks, Recreation, and Cultural Resources Department.

The city was well-prepared to deal with most weather events, as many staff at the time were seasoned by Hurricane Fran just three and a half years earlier. Their protocols meant working in rotating twelve-hour shifts to make sure facilities across the city, including parks and downtown offices, were cleared of snow and accessible immediately after a storm.

“The city had the philosophy where we never closed,” said Hisler. “We may modify operations, but City Hall never closed.”

That mentality was tested by the January 2000 snowstorm, and for more organizations than just local governments. The National Weather Service office in Raleigh also scrambled to bolster its response when wintry precipitation started falling farther west than expected.

Now a senior forecaster at the office, Brandon Locklear was an entry-level meteorologist intern back in 2000, less than a year into his career with the National Weather Service. A native of North Carolina, Locklear knew first-hand how rare our big snow events were, which explains his surprise when this turned into an all-hands-on-deck situation.

“It was my day off, but I got a call that evening and they said ‘hey Brandon, can you come in, we need you’,” he recalled.

Rushing to the office without bringing food even for one emergency shift – let alone for several snowed-in days that would follow – Locklear saw the storm was shaping up very differently than expected.

“It wasn’t for another two or three hours that we realized we were going to get a lot of snow and we had to ramp things up,” he said. “We basically went from zero to 100 in six or eight hours.”

That scramble to adjust the forecast is evident in the Winter Storm Warnings issued during the event. The predicted totals for the Raleigh area seemed to change as quickly as the snow was accumulating: 3 to 6 inches at 11 pm, 6 to 12 inches by 1 am, 8 to 15 inches by 4:45 am, and the eventual totals of up to 20 inches for parts of the northern Piedmont by mid-morning on January 25.

In retrospect, it’s clear that this was anything but a typical snowstorm for North Carolina. Our common wintry setup begins with a shallow dome-like layer of cold air near the ground. Warm, moist air is then flung inland by an offshore low-pressure system, riding up and over that surface cold dome.

That warm air intrusion aloft is like a ticking clock for our snow chances, especially from Raleigh to the south and east, as enough warming eventually puts the mid-levels of the atmosphere above freezing, causing the snow to switch to sleet or freezing rain.

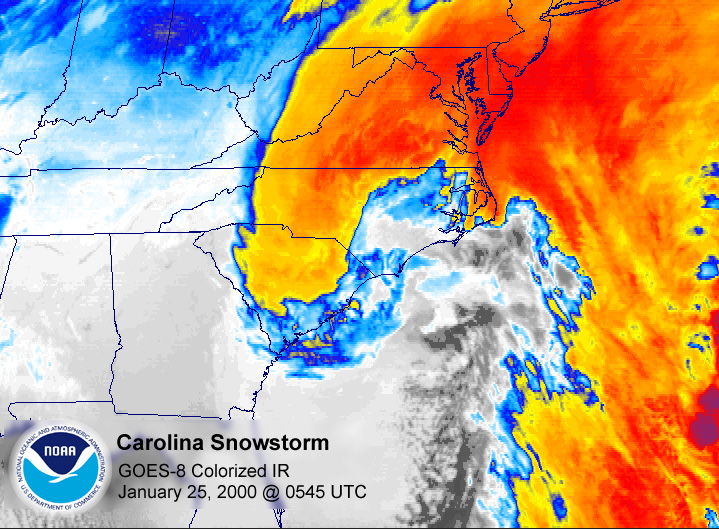

But in this case, we were also sitting under a strong trough in the jet stream — a low-pressure area in the upper atmosphere — that ushered in a deep layer of cold air and ensured the atmosphere was primed for snow.

After that initial period of sleet, the mid-levels of the atmosphere fell entirely below freezing per the measurements collected that night by a weather balloon launched from Greensboro. Thanks to the upper-level reinforcements, those sub-freezing temperatures were locked in place for the duration of the event.

The presence of that trough unusually far south also put us in the playground for jet stream dynamics: processes that provide additional support for lift and precipitation in certain regions around that fast-moving “river of air” more than three miles above the ground.

That acted to enhance the precipitation associated with the surface low-pressure system tracking along our coastline, and even after that system had gone by, the upper-level low prolonged the rising air needed to generate more precipitation throughout the night.

“A lot of times, the [surface] low goes by to the north and the snow will stop, but in that case we had the forcing for ascent well into the next morning,” explained Lackmann. “Once the low moved by to the north, the snow on the back side associated with the upper trough kept falling.”

It was the rare combination, at least in this part of the country, of being cold enough and having the atmospheric support for sustained snowfall without the risk of a precipitation type transition or an early end to the event.

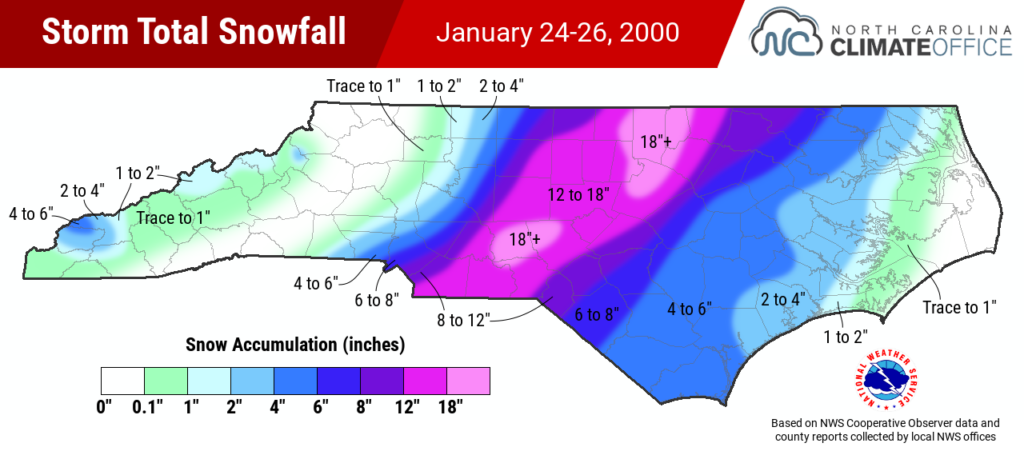

Even rarer was the amount of snow we ended up with. Totals exceeded a foot from Wadesboro to Warrenton, with 14.5 inches in Asheboro, 17 inches in Oxford, and 18 to 24 inches reported across parts of Wake County.

At the Triangle’s official observing location, the Raleigh-Durham International Airport recorded 17.9 inches of snow in 24 hours on January 25 and a storm total of 20.3 inches: both records for the city dating back more than 130 years.

Beyond the basics of this storm’s setup, understanding how Raleigh ended up with record snowfall is a case of atmospheric dominos, plenty of finger-pointing, and the triumph of research.

Untangling a Frayed Forecast

When thunder rumbled in Mobile, AL, just after midnight on January 24, 2000, it wasn’t a sign that snow was seven to ten days away there; that old folklore hardly holds in North Carolina, let alone on the Gulf coast. But as few realized at the time, the storms well to our south that evening would have a profound impact on the heavy snow that Raleigh received less than 24 hours later.

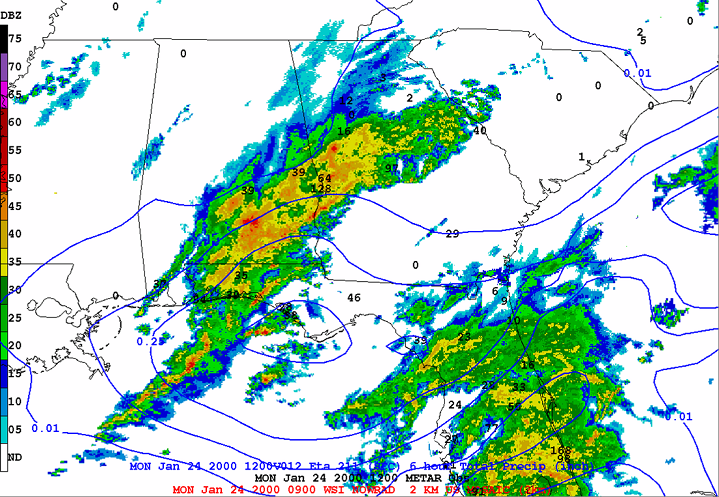

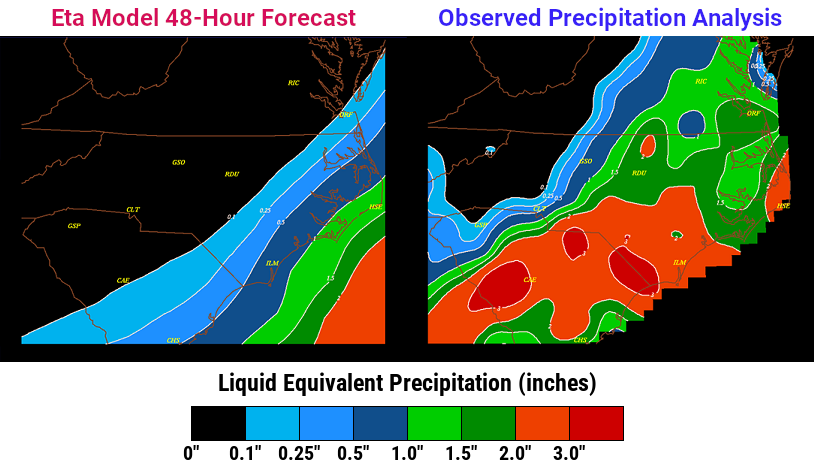

Forecasters at the local National Weather Service office had noticed the thunderstorm activity and how it wasn’t being captured by the forecast models, but they didn’t immediately grasp its impact on the overall storm.

“There was an overconfidence at that time in the meteorological community and the modeling community that there were going to be no surprises, that all models could capture an event like that,” said Locklear, reflecting on the failed model forecast for the January 2000 storm.

Even for an expert like Lackmann, who saw the same feature on weather maps that morning and thought the energy it would impart might add a few extra inches of snow downstream, the potential for a borderline blizzard wasn’t at all apparent.

“I don’t think anyone, given the tools we had at the time, would have said we’d have more than 20 inches of snow,” he said. “Climatologically, it was such a rare occurrence.”

Raleigh’s average annual snowfall at the time was six inches, and the single-storm record of 17.8 inches in March 1927 seemed untouchable, weathering the cold and snowy years in the late 1970s without a serious challenge.

But beginning with those thunderstorms to our south on the morning of January 24, 2000, the right set of ingredients came together in quick succession to produce record-breaking snow totals far beyond what the initial forecasts showed. It was a process that took several years for Lackmann and then-student Michael Brennan – now the director of the National Hurricane Center – to fully unravel.

First, condensation from those thunderstorms along the Gulf coast released energy as latent heat, warming the mid-levels of the atmosphere. That heating induced potential vorticity, or circulation akin to a new area of low pressure. That feature was wrapped up into the main surface low along the coast, helping it strengthen and pull in more moisture even farther west.

And when the upper trough eventually caught the rapidly deepening surface low along the coast, the denser cold air forced the warm air upwards in an explosive process called an instant occlusion.

When Gonski arrived at the National Weather Service office that night, he saw on satellite imagery the telltale comma-shaped signature of that pattern, which he’d previously associated with the potential for heavy rain and flash flooding. In this case, it was a sign of precipitation falling as heavy snow within the cold air mass across the eastern Piedmont.

Given the series of events that all started with a cluster of thunderstorms to our south, it’s reasonable to wonder why the models missed that feature that played such a major role in shifting where the snow fell and boosting its eventual intensity.

“It’s surprising that the models didn’t predict it because it was pretty large in scale and it had pretty heavy precipitation with it, and it was over land, where we have good observations,” said Lackmann.

Soon after the event, speculation swirled that data collected from some upper-air weather balloons had been errantly excluded from model runs at the time. That’s partially true; data from a balloon launched in Peachtree City, GA, was thrown out because, Lackmann said, “the quality control system found too big of a mismatch between that observation and the first guess made by the model.”

In hindsight, that data point was an early sign that the storm was outperforming expectations. However, a later study determined that excluding any single upper-air observation had limited impacts on the models’ depiction of the storm.

A bigger issue was how the models handled those thunderstorms in the first place. They formed almost a mile and half off the ground, above more stable air near the surface, in a process known as elevated convection.

“And the way the models were designed back at that time, they weren’t properly configured to represent elevated convection,” said Lackmann. “That feature proved to be critical.”

After the models missed that initial area of convection, the errors snowballed, growing even larger over time. That meant forecasting little to no liquid precipitation in Raleigh just hours before a turn-of-the-century snowpocalypse was about to unfold.

A Snowed-In City

Now the Associate Dean for College Success and Well-Being in the College of Sciences at NC State University, Dr. Jamila Simpson was a meteorology student in her final semester at NC State in January 2000, and she was closely watching out the window on January 24, knowing that any flakes might be fleeting based on the initial forecasts.

“When they started coming down, they started coming down really hard,” she said. “I could see the parking lot from my dorm room and I could see it covering that really quickly, like within minutes.”

Despite Simpson’s warnings, her suitemates decided to go for a drive that night. They never even made it out of the parking lot before their car got stuck in the sea of snow.

“The amount of snow and the rate it was falling and the way it was sticking let me know this was going to be a bigger problem than what the meteorologists were saying,” said Simpson.

The first report of snow at the Raleigh-Durham airport came at the 8 pm observation. By 1 am, it had intensified to heavy snow, which lasted for six consecutive hours. Thirteen inches of snow fell during that time, including that four-inch-per-hour clip between 5 and 6 am.

At the National Weather Service, the fast-falling snow required more than just updates to the forecast. Staff had to sweep off rooftop satellite dishes all night because the snow was affecting the office’s ability to receive data.

And with the snow building all around, Locklear – the emergency back-up for the night – realized his single shift might turn into a longer time being stuck at the office.

“You can’t leave,” he remembered. “You look around and you’re hunkering down with all your coworkers.”

It took two or three days before Locklear could get home; an initial effort to plow the parking lots just resulted in more snow being pushed up against employees’ cars. That became a common dilemma across the Triangle, particularly for the City of Raleigh as their staff scrambled to find somewhere – anywhere – to move the snow.

“That was the biggest part: where do you put it?” said Hisler. “You can’t create these mounds in front of doorways, and downtown, there isn’t a lot of space.”

The answer, at least for the snow blanketing downtown Raleigh, was loading it on dump trucks and hauling it away to add to a new glacial giant on city-owned land.

“We put it in a mountain in the lower parking lot at Chavis Park,” Hisler remembered.

In Lackmann’s neighborhood in Cary, the snow depth reached up to 24 inches: among the highest totals in the state during that storm. While that much snow wasn’t an unusual sight for the recent transplant from up north, one aspect of this storm in North Carolina was very different.

“What really shocked me coming from New York and Montreal was that there was no snow removal equipment,” he said. ”The snow just sat there, and school was closed the rest of the week and most of the next week.”

Indeed, the Wake County Public School System missed six days of classes. And it could have been even more if not for a slew of crews working twelve-hour shifts, day in and day out, in the wake of the storm.

With the state and county Departments of Transportation already pushed to the limits of their own resources, city staff from the parks department, solid waste services, public utilities, and other groups were deployed to help clear secondary roads, splitting into teams and using the leaf collection zones to divide the city. Even then, enough snow was left on side roads that local schools had to take inspiration from colder climates.

“Up north, we’d have alternate bus routes for inclement weather,” said Hisler. “That’s what we had to do here too, arranging different corners where students could get picked up.”

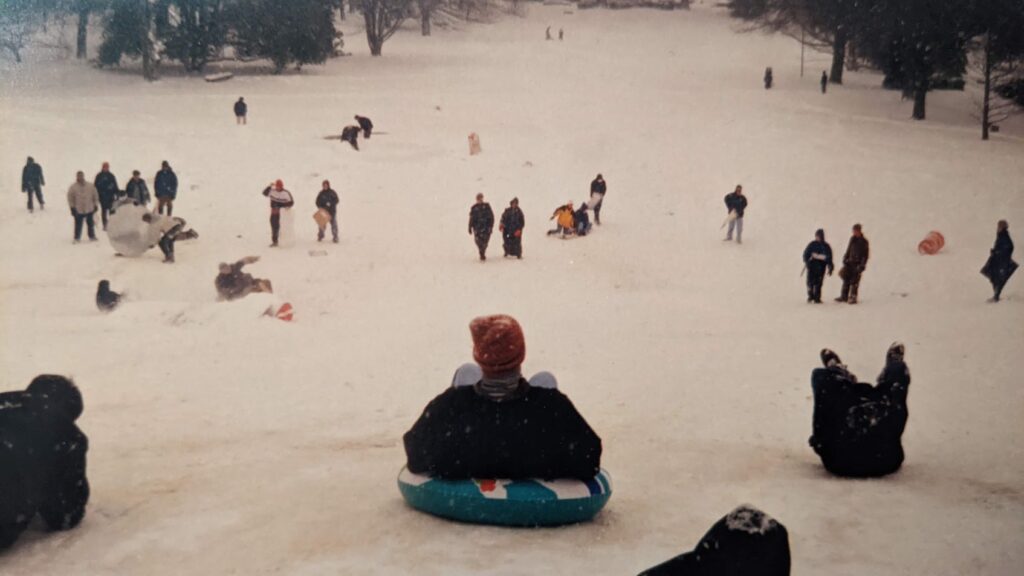

College classes were cancelled too, which made snow-covered campuses a playground for inventive students.

“You’re being really creative because you’re not prepared,” said Simpson. “You don’t have the equipment to go sledding or to be warm, so there was a lot of sharing of coats and gloves. Sledding on trays from the cafeteria. Some people tried to use trash cans.”

“My boyfriend at the time, now my husband, had an inflatable inner tube, and we went sledding. There were snowball fights, and lots of people made snowmen. We were all sledding down the Court of North Carolina.”

While students played, university staff scrambled. Dining hall workers were unable to get on NC State’s campus, so resident advisors prepared meals and delivered them to students in the dorms.

The City of Raleigh was equally industrious, using the convention center downtown and its catering staff to feed workers, and even house some who lived too far away for safe travels through the snow.

“A lot of our workforce came from Johnston County, and the risk of going up and down I-40 was high, especially at night,” Hisler recalled.

As for the Delaware native who insisted on driving home after work each day – “I’m stubborn, I’m a northerner,” he joked – Hisler learned to stay in the single plowed lane down major thoroughfares like Capital Boulevard and take it slow and steady in the subdivisions.

“Stay in the ruts and don’t make any sudden movements or you’ll be in trouble,” he said.

That was one of many lessons that 20 inches of snow taught a surprised city, including the forecasters who never saw a storm of that size coming.

A Lasting Legacy

For the weather modeling community, the year 2000 was a wakeup call particularly because of the events in North Carolina. In addition to the missed snow forecast in January, models had the opposite problem that December, predicting more than a foot of snow in Raleigh when all that happened was a few flurries.

“Between those two storms, the meteorologists’ reputation took a bit of a hit,” said Lackmann. “Those two events were a call for help to try to learn more about how to solve these numerical modeling issues.”

For the frontline forecasters like Locklear at local National Weather Service offices, they heard first-hand frustration from the public about those missed predictions.

“We took a lot of heat from that,” he said, “but we took that as a challenge to get to work and try to figure out how to do better.”

That meant a closer collaboration with researchers such as Lackmann and Brennan to understand why those forecasts went wrong and how to recognize features the models might miss. Lackmann and two former students later developed a paper titled Potential Vorticity Thinking in Operations outlining just such a framework.

The communications were a two-way street, and that included forecasters raising concerns with researchers about issues they saw with the models. Among those was another winter weather hurdle with how the models depicted freezing rain, which led to further research by Lackmann.

More recently, those informal post-event email chains paved the way for NOAA’s Model Evaluation Group, which reviews the hits and misses of forecast models every week.

And despite advancements in the models over the past 25 years, there’s still a need for critical thinking among forecasters so they never blindly trust what any model spits out.

“Yes, we’re looking at forecast models three days out, seven days out, ten days out, but when you start looking at satellite data, radar data, and observations, you can pick up on some things,” said Locklear. “That’s where forecaster experience comes in.”

To that end, he noted that meteorologists at the National Weather Service in Raleigh analyze surface weather maps by hand during each shift to find key features and patterns that may not be obvious in computer-generated output.

So with those advancements in knowledge and technology, if a similar event happened today, is there any chance we could be caught by surprise again?

“I suspect the grocery stores would be depleted days before the storm,” surmised Lackmann, who said current models should be able to pick up on the heavy snow potential of such a potent pattern three to five days ahead of time.

For Simpson, a newly degreed meteorologist just a few months after the January 2000 snowstorm, the challenges of its fast-changing forecast inspired her to go back to school for a PhD in science communication.

“From that experience and some other ones, it really impacted my thought process on how scientists communicate to the public so they feel well-informed and they trust you as a source,” she said.

Behind the scenes, the City of Raleigh made changes to improve their ability to handle snowstorms, such as adding a second salt barn in northwest Raleigh and building an extra large locker room at Marsh Creek Community Center, which was opened in 2010 and serves as a backup site for support staff.

And the city is now better prepared for any incident — weather-related or otherwise — after implementing department-specific emergency operations centers, developing a formal emergency operations plan, and creating an emergency operations work unit managed by the fire department.

“That all played into the lessons learned, putting the city in a better position to respond,” Hisler noted.

When it comes to wintry weather, the minor events have drawn the most attention in the Raleigh area over the past 25 years for all the wrong reasons — see the “half-inch disaster” from 2005 or the meme-inspiring snow day snarl in 2014.

But the January 2000 storm put Raleigh in the news for a different reason. The storm’s “surprise punch” headlined the New York Times, and CNN led with North Carolina’s state of emergency just a few months after another such event from Hurricane Floyd in September 1999.

Even 25 years later, it’s a storm that continues to live large in the memories of long-time residents – “for a lot of us, it was the biggest snowstorm we’ve ever experienced in our lifetimes,” said Locklear – and that’s still apparent in our current climate measurements.

The month of January 2000, with 25.8 inches of total snow in Raleigh, single-handedly adds almost an inch (0.86”) to the 30-year average snowfall, which now stands at a little over five inches per year.

Even amid our recent stretch of long-running snow droughts ended by icy disappointment, the January 2000 storm is a reminder that for one rare event in the not-too-distant past, Raleigh was the surprise snowfall king of the south.

And it’s the reason why whenever flurries are in the forecast, locals – with a mix of hope and sarcasm – will dust off their snow boots and snicker, I’ve heard that one before.