Hurricanes and the Outer Banks go together like cats and mice. It’s not exactly a productive pairing for one of them, but it’s also hard to imagine life any other way.

But for decades, it seemed, there was an uneasy and perhaps unnatural truce between the two. Even as the Atlantic experienced its own awakening in the mid-1990s, the Outer Banks – by then, built-up and bustling around a robust summertime tourism industry – continued to be spared from a direct hit.

That all changed twenty years ago, when a monster storm made a beeline for our barrier islands and quite literally left a mark that is still remembered today, and apparent in how the area prepares for and talks about hurricanes.

A Storm for the Modern Era

The context of Hurricane Isabel and its impact on the region is most eloquently told by Karen Amspacher, the executive director of the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center, located on Harkers Island near Cape Lookout.

“Isabel was a shot across the bow for a certain generation, and that was the storm of record,” she said. “Ahead of that, it had just been near misses. Fran went inland, Floyd went inland. But when it comes to a storm taking a serious hit, Isabel went right over Core Banks and the flooding was amazing.”

The region’s history with hurricanes is long, but during the entire 20th century, perhaps the only storm comparable to Isabel was the so-called Chesapeake-Potomac hurricane in August 1933, which hit northern Hatteras Island as a Category-1.

Sixty years later, the region had a close call from Hurricane Emily, which brushed Cape Hatteras as a Category-3 in 1993. That storm changed the way residents and forecasters approached hurricanes – especially as local forecasts for the area were going through a change of their own.

In the mid-1990s, the National Weather Service underwent a modernization and restructuring. Previously, it operated 52 forecast offices – with roughly one per state – and 204 local offices that were responsible for observations and severe weather warnings over a smaller area.

As part of the restructuring, that two-tiered structure would be replaced by a set of 115 weather forecast offices, or WFOs, with each having roughly the same responsibilities, its own local radar, and a staff consisting mostly of degreed meteorologists, rather than the technicians who previously made up most of the local office personnel.

That change meant the Weather Service office in Hatteras was shut down, and forecast responsibilities for the island shifted to the newly created WFO in Newport/Morehead City.

John Elardo is a senior forecaster at that office, and the last remaining staff member who has been there since its inception. Back then, he remembers hearing worries from folks on Hatteras Island, especially surrounding tropical events in the wake of Emily.

“After losing their prestigious weather office, they wondered if they would still have the same level of service as they got from the office in their backyard,” he said.

To ease those concerns, Elardo and the other staff from Newport worked to build relationships with local emergency managers and the public to make sure their needs would still be met, even though the National Weather Service office was no longer located on the Outer Banks.

They didn’t have to wait long – just a decade after Emily, and only eight years after the Newport office opened – before those preparations were put to the test.

“Isabel was the first major hurricane we had to worry about, and with the track coming toward the Outer Banks, we were really concerned about what that meant,” he said. “We heard from people about what Emily did, and it was just a glancing blow for Hatteras Island.”

Emily inundated the area with rain and storm surge, which displaced 25% of the island’s permanent population from their homes. And while it was a Category-3 at its closest approach, Isabel was on pace to be far stronger.

More than Meets the Eye

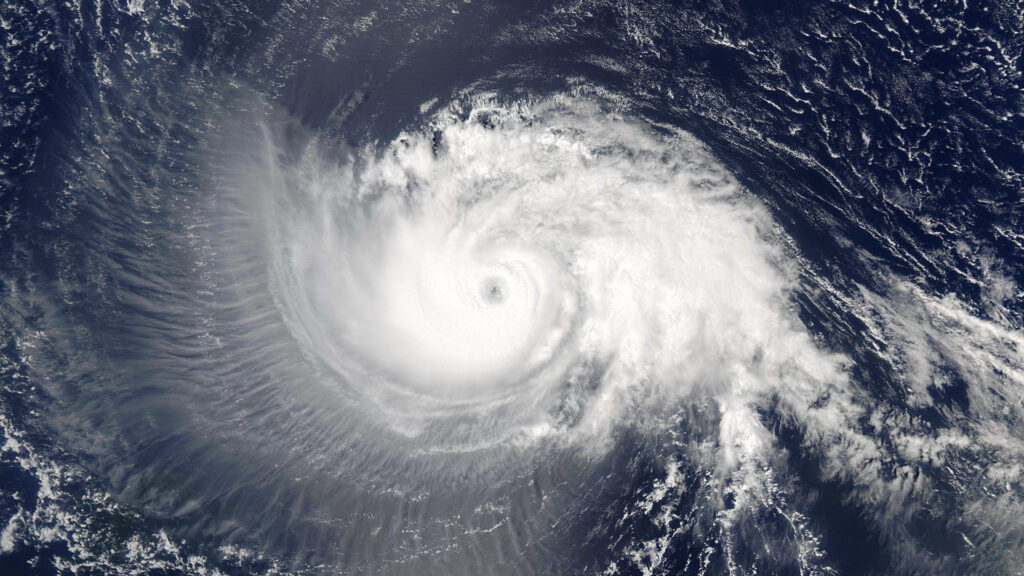

Isabel first formed on September 6, 2003, when it was 1,000 miles off the coast of Africa, and on September 11, it achieved Category-5 intensity – a designation it would hold for a 24 consecutive hours as it tracked north of the Caribbean islands.

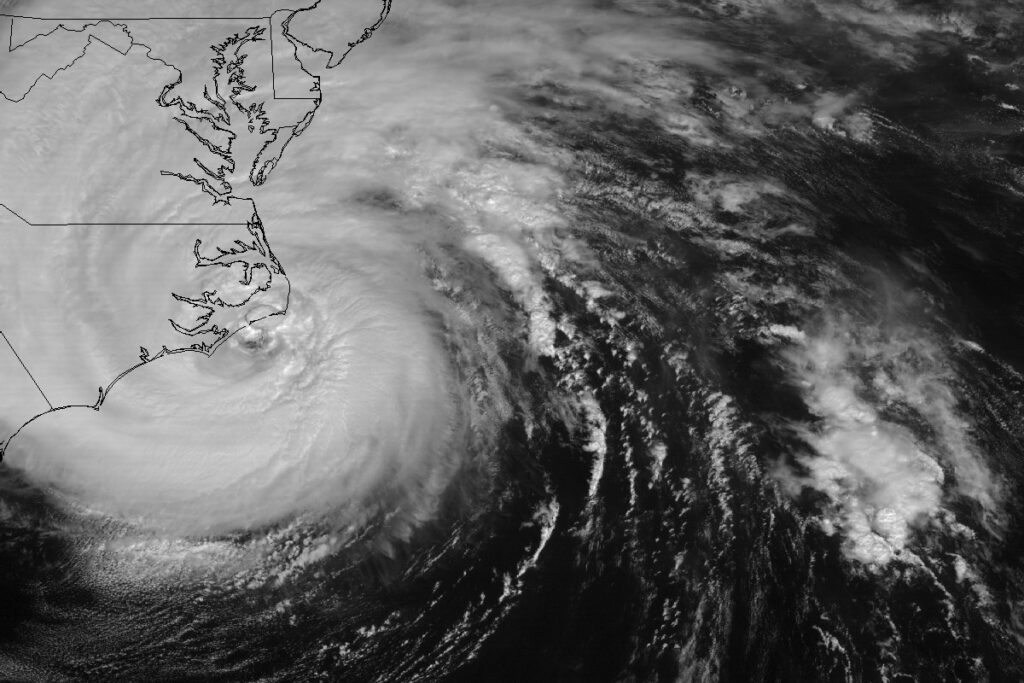

After turning toward the northwest on September 15, still a strong Category-4 hurricane, Isabel was on a track aimed at the Outer Banks.

By the following day, it entered a harsher environment with increased westerly wind shear. It weakened to a Category-2, but it held that strength until its landfall along the Core Banks on the afternoon of September 18. And far from relief, it inspired plenty of concerns for the damage it might cause along the coastline.

“Even though it was to down a Category-2 storm, it did make a direct landfall on the Outer Banks, and we know even strong Nor’easters give them issues,” said Elardo.

One long-time resident who vividly remembers Isabel is Danny Couch. Today, he’s a Dare County commissioner and realtor serving Hatteras Island. In 2003, his family owned a local real estate company, so he stuck around during Isabel with hopes of giving property owners a damage update after the storm hit.

But as he discovered, even though Isabel had weakened, it showed the signs of a far fiercer storm when it arrived.

“The ocean didn’t get the memo,” said Couch.

He recalls watching the towering waves coming in ahead of the storm and breaking over the open ocean, instead of the sandbars closer to the shore.

“It was like a washing machine on a planetary scale,” he said.

And it wasn’t just his imagination. The swells from Isabel carried characteristics of its Category-4 past due to a phenomenon called captured fetch. Because it took such a straight and direct path to North Carolina, the same seas it whipped up earlier in its life were still in toe when Isabel reached us.

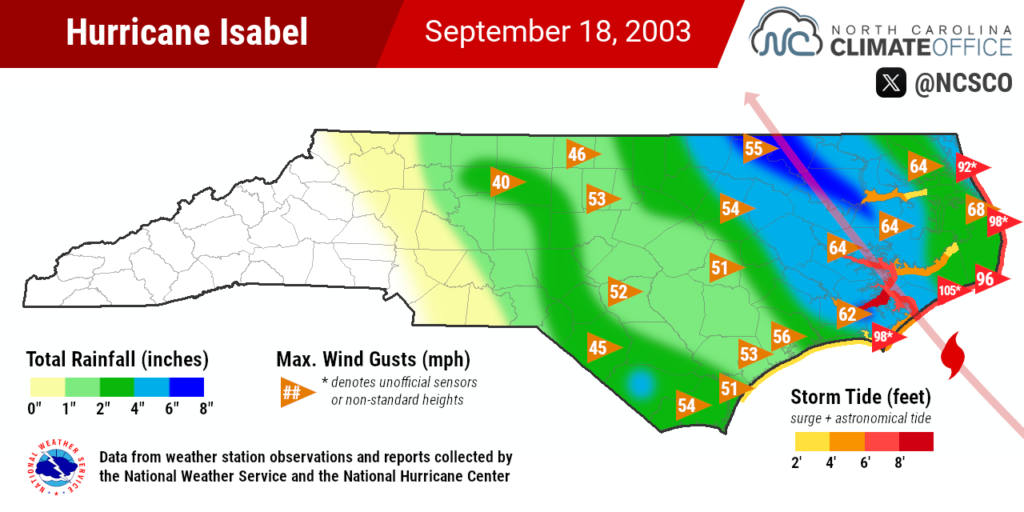

The result was a significant storm tide – the combination of the storm surge with the astronomical high tide, with which Isabel’s landfall unfortunately lined up – that reached almost 8 feet in Hatteras and Duck, and 10.5 feet on the Neuse River in southern Craven County, based on observations collected by the National Hurricane Center.

“And you don’t have to be a math prodigy to understand what that will do,” added Couch.

Stories of Survival

During the height of the storm, the scenes were downright apocalyptic, and they reminded Couch of just such a description from one of our historical hurricanes.

In August of 1899, a storm that had previously hit Puerto Rico later reached eastern North Carolina and came ashore on the north end of Ocracoke Island as a Category-3.

S. L. Dosher, the Weather Bureau observer on Hatteras, described the storm thusly:

The howling wind, the rushing and roaring tide and the awful sea which swept over the beach and thundered like a thousand pieces of artillery made a picture which was at once appalling and terrible and the like of which Dante’s Inferno could scarcely equal.

Those same words came to Couch’s mind as he recalled the scenes on the island during Isabel.

There was the story of John and Judy Hardison, who managed the Durant Station condominiums, clinging to tree branches when their house was swept away and the water came rushing in all around them.

The condos, built on the site of a former lifesaving station at the north end of Hatteras Village, were not as lucky. They were leveled by Isabel and later rebuilt.

Then there’s the tale of Jeff Oden, who used a surfboard as a makeshift lifeboat to get through the flooding and reach the Sea Gull Motel, which he owned, and rescue his daughter as the water rose all around her.

Not everyone on a surfboard was there out of necessity. Couch remembers surfers showing up who foolishly thought Isabel was time to hang ten. He said volunteer firefighters in Buxton marked the surfers’ hands so that they could identify them if they were casualties of the storm.

“They told them you’ve got to understand that this is a barrier island,” said Couch. “If the road goes, you’re not leaving.”

Damage at the Coast

The road did go, and spectacularly, during Isabel. Perhaps the most visible signature from the storm was a breach in the narrowest part of Hatteras Island, which was nicknamed Isabel Inlet. That 1,700-foot wide inlet swallowed a section of Highway 12, which left Hatteras Village and its residents cut off from the rest of the state.

It took just over two months, until November 22, for the road to be reopened to the public, after what Couch called “the Elvis of dredges” was brought in to fill in the breach with sand, and the broken road was rebuilt.

Elsewhere along the Outer Banks, the damage from Isabel was widespread and severe. The flooding on Ocracoke Island was waist-high. The winds and waves damaged or destroyed the piers in Nags Head, Rodanthe, and Frisco. Dozens of houses and motels were knocked off their pilings, and thousands of others sustained damage.

Altogether, the damage in the state was estimated at $450 million in 2003, or more than $740 million today, adjusted for inflation.

Harkers Island and other Down East communities in Carteret County didn’t get as much attention after the storm, Amspacher said, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t suffer plenty of damage of their own.

“After Isabel, when the inlet got cut open above Hatteras Village, that’s where all the press was,” she said.

“Yes, it cut a hole in the road, but in a very small community of about 200 people Down East, the word was every house but about six were flooded. But that wasn’t where the traffic was, and that was a community people didn’t know.”

Up to five inches of rain, combined with the 4 to 7-foot storm tide along the Core Sound, damaged or destroyed 90% of homes and businesses in the town of Sea Level. In nearby Portsmouth Village, which had been flooded by the 1933 hurricane, Isabel caused significant damage to several historic properties, including outbuildings torn from their foundations near the Henry Pigott House, constructed more than a century earlier in 1902.

And while the surge and flooding were generally worse than the winds, the storm was still a wind-maker to be sure. Gusts measured by unofficial sensors reached up to 105 mph in Ocracoke and 98 mph in Harkers Island and Oregon Inlet. The National Ocean Service station in Hatteras recorded a peak gust of 96 mph before the station was destroyed, according to the National Hurricane Center.

Because of the gusty winds, Isabel knocked out power to approximately 762,000 people across eastern North Carolina.

Isabel’s Lasting Legacy

In the twenty years since Isabel, the Outer Banks has not taken any other direct hits from hurricanes, but there have been several close calls and damaging storms nonetheless.

Hurricane Irene hit in 2011, and Amspacher said homeowners Down East who hadn’t elevated their houses after Isabel were flooded again then. Florence in 2018 was another devastating flood event for those low-lying communities in eastern Carteret County, but the experience from Isabel was at least useful in that case.

“A lot of the recovery mechanisms that were considered a one-off response for Isabel got pulled back out for Florence,” said Amspacher.

That includes a partnership between the Carteret County Public Schools Foundation and the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center to support local families following Isabel and the storms since.

For the National Weather Service office in Newport, which now has almost 30 years of experience forecasting for the Outer Banks, they still remember those early storms such as Isabel for their impacts far beyond just the winds.

“Floyd and Isabel were two really important storms for our area because they taught our office a lot about the impacts, and not to just consider the category,” said Elardo. “I was shocked by how much damage an ‘only’ Category-2 storm did.”

While Isabel was a well-forecasted storm – an NWS service assessment noted that Isabel’s forecast track had lower error than the average for that era – more recent improvements in storm surge modeling, combined with their experience gained over time, has put the National Weather Service in a better position to serve areas like Hatteras Island during future storms.

“We have the best of both worlds now,” said Elardo. “We have a lot of institutional knowledge about areas that are susceptible to flooding, or where flooding can be the worst, and a lot of advancement in storm surge forecasting as well.”

In Dare County, those one-time concerns about losing their local forecast office have been unfounded, and Couch said the island has a great relationship with the WFO in Newport. The Weather Service even has an office within Dare County’s Emergency Operations Center in Manteo, the need for which arose from Isabel after “Hatteras Island became the Hatteras islands,” Couch noted.

Thanks to the widespread adoption of cell phones, and with a storm like Isabel still on their minds, the county also implemented an emergency alert system, which was put to the test during both Matthew and Dorian.

“Communication is key,” said Couch. “If we have another Isabel and authorities are telling you what is happening, you better listen. Make your preparations now, be ready for the worst, and evacuate if at all possible. Your stuff can be replaced; your well-being cannot.”

Since Isabel, the Outer Banks has seen occasional overwash from both tropical and non-tropical events, but nothing has come close to that hurricane in September 2003.

So while the cat has been away, the mice have been at play – as evidenced by the nearly $2 billion in tourist spending along the Outer Banks last year.

But as history has proven, it’s only a matter of time before the cat decides to pounce again. And when it does, it may be those scenes and stories from Isabel, rather than storms a century earlier, that spring to mind.